| Snow leopard Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | P. uncia

|

| Binomial name | |

| Panthera uncia (Schreber, 1775)

| |

| |

| Distribution of the snow leopard, 2017[1] | |

| Synonyms | |

The snow leopard (Panthera uncia), occasionally called ounce, is a species of large cat in the genus Panthera of the family Felidae. The species is native to the mountain ranges of Central and South Asia. It is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List because the global population is estimated to number fewer than 10,000 mature individuals and is expected to decline about 10% by 2040. It is mainly threatened by poaching and habitat destruction following infrastructural developments. It inhabits alpine and subalpine zones at elevations of 3,000–4,500 m (9,800–14,800 ft), ranging from eastern Afghanistan, the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau to southern Siberia, Mongolia and western China. In the northern part of its range, it also lives at lower elevations.

Taxonomically, the snow leopard was long classified in the monotypic genus Uncia. Since phylogenetic studies revealed the relationships among Panthera species, it has since been considered a member of that genus. Two subspecies were described based on morphological differences, but genetic differences between the two have not yet been confirmed. It is therefore regarded as a monotypic species. The species is widely depicted in Kyrgyz culture.

Naming and etymology

The Old French word once, which was intended to be used for the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx), is where the Latin name uncia and the English word ounce both originate. Once is believed to have originated from a previous form of the word lynx through a process known as false splitting. The word once was originally considered to be pronounced as l'once, where l' stands for the elided form of the word la ('the') in French. Once was then understood to be the name of the animal.[2] The word panther derives from the classical Latin panthēra, itself from the ancient Greek πάνθηρ pánthēr, which was used for spotted cats.[3]

Taxonomy and evolution

Felis uncia was the scientific name used by Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber in 1777 who described a snow leopard based on an earlier description by Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, assuming that the cat occurred along the Barbary Coast, in Persia, East India and China.[4] The genus name Uncia was proposed by John Edward Gray in 1854 for Asian cats with a long and thick tail.[5] Felis irbis, proposed by Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg in 1830, was a skin of a female snow leopard collected in the Altai Mountains. He also clarified that several leopard (P. pardus) skins were previously misidentified as snow leopard skins.[6] Felis uncioides proposed by Thomas Horsfield in 1855 was a snow leopard skin from Nepal in the collection of the Museum of the East India Company.[7]

Uncia uncia was used by Reginald Innes Pocock in 1930 when he reviewed skins and skulls of Panthera species from Asia. He also described morphological differences between snow leopard and leopard skins.[8] Panthera baikalensis-romanii proposed by a Russian scientist in 2000 was a dark brown snow leopard skin from the Petrovsk-Zabaykalsky District in southern Transbaikal.[9]

The snow leopard was long classified in the monotypic genus Uncia.[10] They were subordinated to the genus Panthera based on results of phylogenetic studies.[11][12][13][14]

Until spring 2017, there was no evidence available for the recognition of subspecies. Results of a phylogeographic analysis indicate that three subspecies should be recognised:[15]

- P. u. uncia in the range countries of the Pamir Mountains

- P. u. irbis in Mongolia, and

- P. u. uncioides in the Himalayas and Qinghai.

This view has been both contested and supported by different researchers.[16][17][18][19]

Additionally, an extinct subspecies Panthera uncia pyrenaica was described in 2022 based on material found in France. Its fossil was dated to the early Middle Pleistocene, around 0.57 to 0.53 million years ago.[20]

Evolution

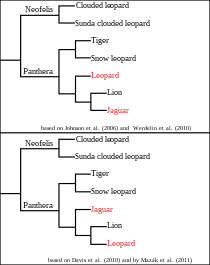

Based on the phylogenetic analysis of the DNA sequence sampled across the living Felidae, the snow leopard forms a sister group with the tiger (P. tigris). The genetic divergence time of this group is estimated at 4.62 to 1.82 million years ago.[11][21] The snow leopard and the tiger probably diverged between 3.7 to 2.7 million years ago.[12] Panthera originates most likely in northern Central Asia. Panthera blytheae excavated in western Tibet's Ngari Prefecture has been initially described the oldest known Panthera species and exhibits skull characteristics similar to the snow leopard,[23] though its taxonomic placement has been disputed by other researchers who suggest that the species likely belongs to a different genus.[24][25]

The mitochondrial genomes of the snow leopard, the leopard and the lion (P. leo) are more similar to each other than their nuclear genomes, indicating that their ancestors hybridised at some point in their evolution.[26]

Characteristics

The snow leopard's fur is whitish to grey with black spots on the head and neck, with larger rosettes on the back, flanks and bushy tail. Its muzzle is short, its forehead domed, and its nasal cavities are large. The fur is thick with hairs measuring 5 to 12 cm (2.0 to 4.7 in) in length, and its underbelly is whitish. They are stocky, short-legged, and slightly smaller than other cats of the genus Panthera, reaching a shoulder height of 56 cm (22 in), and ranging in head to body size from 75 to 150 cm (30 to 59 in). Its tail is 80 to 105 cm (31 to 41 in) long.[27] Males average 45 to 55 kg (99 to 121 lb), and females 35 to 40 kg (77 to 88 lb).[28] Occasionally, large males reaching 75 kg (165 lb) have been recorded, and small females under 25 kg (55 lb).[29] Its canine teeth are 28.6 mm (1.13 in) long and are more slender than those of the other Panthera species.[30]

The snow leopard shows several adaptations for living in cold, mountainous environments. Its small rounded ears help to minimize heat loss, and its broad paws effectively distribute the body weight for walking on snow. Fur on the undersides of the paws enhances its grip on steep and unstable surfaces, and helps to minimize heat loss. Its long and flexible tail helps to balance the cat in the rocky terrain. The tail is very thick due to fat storage, and is covered in a thick layer of fur, which allows the cat to use it like a blanket to protect its face when asleep.[31]

The snow leopard differs from the other Panthera species by a shorter muzzle, an elevated forehead, a vertical chin and a less developed posterior process of the lower jaw.[32] Despite its partly ossified hyoid bone, a snow leopard cannot roar, as its 9 mm (0.35 in) short vocal folds provide little resistance to airflow.[33][34] Its nasal openings are large in relation to the length of its skull and width of its palate; thanks to their size the volume of air inhaled with each breath is optimised, and the cold dry air becomes warmer.[35] It is not especially adapted to high-altitude hypoxia.[36]

Distribution and habitat

The snow leopard is distributed from the west of Lake Baikal through southern Siberia, in the Kunlun Mountains, Altai Mountains, Sayan and Tannu-Ola Mountains, in the Tian Shan, through Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan to the Hindu Kush in eastern Afghanistan, Karakoram in northern Pakistan, in the Pamir Mountains, the Tibetan Plateau and in the high elevations of the Himalayas in India, Nepal and Bhutan. In Mongolia, they inhabit the Mongolian and Gobi Altai Mountains and the Khangai Mountains. In Tibet, they occur up to the Altyn-Tagh in the north.[28][37] They inhabit alpine and subalpine zones at elevations of 3,000 to 4,500 m (9,800 to 14,800 ft), but also lives at lower elevations in the northern part of their range.[38]

Potential snow leopard habitat in the Indian Himalayas is estimated at less than 90,000 km2 (35,000 sq mi) in Jammu and Kashmir, Ladakh, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh, of which about 34,000 km2 (13,000 sq mi) is considered good habitat, and 14.4% is protected. In the beginning of the 1990s, the Indian snow leopard population was estimated at 200–600 individuals living across about 25 protected areas.[37] The Snow Leopard Population Assessment in India (SPAI) Programme counted the number of snow leopards between 2019 and 2023 and found their number to be 718, with 477 in Ladakh, 124 in Uttarakhand, 51 in Himachal Pradesh, 36 in Arunachal Pradesh, 21 in Sikkim, and nine in Jammu and Kashmir.[39]

In summer, the snow leopard usually lives above the tree line on alpine meadows and in rocky regions at elevations of 2,700 to 6,000 m (8,900 to 19,700 ft). In winter, they descend to elevations around 1,200 to 2,000 m (3,900 to 6,600 ft). They prefer rocky, broken terrain, and can move in 85 cm (33 in) deep snow, but prefers to use existing trails made by other animals.[29]

Snow leopards were recorded by camera traps at 16 locations in northeastern Afghanistan's isolated Wakhan Corridor.[40]

Behavior and ecology

The snow leopard's vocalizations include meowing, grunting, prusten and moaning. They can purr when exhaling.[27]

It is solitary and mostly active at dawn till early morning, and again in afternoons and early evenings. They mostly rest near cliffs and ridges that provide vantage points and shade. In Nepal's Shey Phoksundo National Park, the home ranges of five adult radio-collared snow leopards largely overlapped, though they rarely met. Their individual home ranges ranged from 12 to 39 km2 (4.6 to 15.1 sq mi). Males moved between 0.5 and 5.45 km (0.31 and 3.39 mi) per day, and females between 0.2 and 2.25 km (0.12 and 1.40 mi), measured in straight lines between survey points. Since they often zigzagged in the precipitous terrain, they actually moved up to 7 km (4.3 mi) in a single night.[41] Up to 10 individuals inhabit an area of 100 km2 (40 sq mi); in habitats with sparse prey, an area of 1,000 km2 (400 sq mi) usually supports only five individuals.[42]

A study in the Gobi Desert from 2008 to 2014 revealed that adult males used a mean home range of 144–270 km2 (56–104 sq mi), while adult females ranged in areas of 83–165 km2 (32–64 sq mi). Their home ranges overlapped less than 20%. These results indicate that about 40% of the 170 protected areas in their range countries are smaller than the home range of a single male snow leopard.[43]

Snow leopards leave scent marks to indicate their territories and common travel routes. They scrape the ground with the hind feet before depositing urine or feces, but also spray urine onto rocks.[29] Their urine contains many characteristic low molecular weight compounds with diverse functional groups including pentanol, hexanol, heptanol, 3-octanone, nonanal and indole, which possibly play a role in chemical communication.[44]

Hunting and diet

The snow leopard is a carnivore and actively hunts its prey. Its preferred wild prey species are Himalayan blue sheep (Pseudois nayaur), Himalayan tahr (Hemitragus jemlahicus), argali (Ovis ammon), markhor (Capra falconeri) and wild goat (C. aegagrus). It also preys on domestic livestock.[45][46] It prefers prey ranging in weight from 36 to 76 kg (79 to 168 lb), but also hunts smaller mammals such as Himalayan marmot (Marmota himalayana), pika and vole species. Its diet depends on prey availability and varies across its range and season. In the Himalayas, it preys mostly on Himalayan blue sheep, Siberian ibex (C. sibirica), white-bellied musk deer (Moschus leucogaster) and wild boar (Sus scrofa). In the Karakoram, Tian Shan, Altai and Mongolia's Tost Mountains, its main prey consists of Siberian ibex, Thorold's deer (Cervus albirostris), Siberian roe deer (Capreolus pygargus) and argali.[47][48] Snow leopard feces collected in northern Pakistan also contained remains of rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), masked palm civet (Paguma larvata), Cape hare (Lepus capensis), house mouse (Mus musculus), Kashmir field mouse (Apodemus rusiges), grey dwarf hamster (Cricetulus migratorius) and Turkestan rat (Rattus pyctoris).[49] In 2017, a snow leopard was photographed carrying a freshly killed woolly flying squirrel (Eupetaurus cinereus) near Gangotri National Park.[50] In Mongolia, domestic sheep comprises less than 20% of its diet, although wild prey has been reduced and interactions with people are common.[48] It is capable of killing most ungulates in its habitat, with the probable exception of the adult male wild yak. It also eats grass and twigs.[29]

The snow leopard actively pursues prey down steep mountainsides, using the momentum of its initial leap to chase animals for up to 300 m (980 ft). Then it drags the prey to a safe location and consumes all edible parts of the carcass. It can survive on a single Himalayan blue sheep for two weeks before hunting again, and one adult individual apparently needs 20–30 adult blue sheep per year.[1][29] Snow leopards have been recorded to hunt successfully in pairs, especially mating pairs.[51]

The snow leopard is easily driven away from livestock and readily abandons kills, often without defending itself.[29] Only two attacks on humans have been reported, both near Almaty in Kazakhstan, and neither were fatal. In 1940, a rabid snow leopard attacked two men; and an old, toothless emaciated individual attacked a person passing by.[52][53]

Reproduction and life cycle

Snow leopards become sexually mature at two to three years, and normally live for 15–18 years in the wild. In captivity they can live for up to 25 years. Oestrus typically lasts five to eight days, and males tend not to seek out another partner after mating, probably because the short mating season does not allow sufficient time. Paired snow leopards mate in the usual felid posture, from 12 to 36 times a day. They are unusual among large cats in that they have a well-defined birth peak. They usually mate in late winter, marked by a noticeable increase in marking and calling. Females have a gestation period of 90–100 days, and the cubs are born between April and June.[29] A litter usually consists of two to three cubs, in exceptional cases there can be up to seven.[52]

The female gives birth in a rocky den or crevice lined with fur shed from her underside. The cubs are born blind and helpless, although already with a thick coat of fur, and weigh 320 to 567 g (11.3 to 20.0 oz). Their eyes open at around seven days, and the cubs can walk at five weeks and are fully weaned by 10 weeks. The cubs leave the den when they are around two to four months of age.[29] Three radio-collared snow leopards in Mongolia's Tost Mountains gave birth between late April and late June. Two female cubs started to part from their mothers at the age of 20 to 21 months, but reunited with them several times for a few days over a period of 4–7 months. One male cub separated from its mother at the age of about 22 months, but stayed in her vicinity for a month and moved out of his natal range at 23 months of age.[54]

The snow leopard has a generation length of eight years.[55]

Threats

Major threats to the population include poaching and illegal trade of its skins and body parts.[1] Between 1999 and 2002, three live snow leopard cubs and 16 skins were confiscated, 330 traps were destroyed and 110 poachers were arrested in Kyrgyzstan. Undercover operations in the country revealed an illegal trade network with links to Russia and China via Kazakhstan. The major skin trade center in the region is the city of Kashgar in Xinjiang.[56] In Tibet and Mongolia, skins are used for traditional dresses, and meat in traditional Tibetan medicine to cure kidney problems; bones are used in traditional Chinese and Mongolian medicine for treating rheumatism, injuries and pain of human bones and tendons. Between 1996 and 2002, 37 skins were found in wildlife markets and tourist shops in Mongolia.[57] Between 2003 and 2016, 710 skins were traded, of which 288 skins were confiscated. In China, an estimated 103 to 236 animals are poached every year, in Mongolia between 34 and 53, in Pakistan between 23 and 53, in India from 21 to 45, and in Tajikistan 20 to 25. In 2016, a survey of Chinese websites revealed 15 advertisements for 44 snow leopard products; the dealers offered skins, canine teeth, claws and a tongue.[58] In September 2014, nine snow leopard skins were found during a market survey in Afghanistan.[59]

Greenhouse gas emissions will likely cause a shift of the treeline in the Himalayas and a shrinking of the alpine zone, which may reduce snow leopard habitat by an estimated 30%.[60]

Where snow leopards prey on domestic livestock, they are subject to human–wildlife conflict.[1] The loss of natural prey due to overgrazing by livestock, poaching, and defense of livestock are the major drivers for the ever decreasing snow leopard population.[29] Livestock also cause habitat degradation, which, alongside the increasing use of forests for fuel, reduces snow leopard habitat.[61]

Conservation

| Country | Year | Estimate |

|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 2016 | 50–200[62] |

| Bhutan | 2016 | 79–112[63] |

| China | 2016 | 4,500[64] |

| India | 2016 | 516–524[65] |

| Kazakhstan | 2016 | 100–120[66] |

| Kyrgyzstan | 2016 | 300–400[67] |

| Mongolia | 2016 | 1,000[68] |

| Nepal | 2016 | 301–400[69] |

| Pakistan | 2016 | 250-420[70] |

| Russia | 2016 | 70–90[71] |

| Tajikistan | 2016 | 250–280[72] |

| Uzbekistan | 2016 | 30–120[73] |

The snow leopard is listed in CITES Appendix I.[28] They have been listed as threatened with extinction in Schedule I of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals since 1985.[57] Hunting snow leopards has been prohibited in Kyrgyzstan since the 1950s.[56] In India, the snow leopard is granted the highest level of protection under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, and hunting is sentenced with imprisonment of 3–7 years.[65] In Nepal, they have been legally protected since 1973, with penalties of 5–15 years in prison and a fine for poaching and trading them.[74] Since 1978, they have been listed in the Soviet Union’s Red Book and is still inscribed today in the Red Data Book of the Russian Federation as threatened with extinction. Hunting snow leopards is only permitted for the purposes of conservation and monitoring, and to eliminate a threat to the life of humans and livestock. Smuggling of snow leopard body parts is punished with imprisonment and a fine.[75] Hunting snow leopards has been prohibited in Afghanistan since 1986.[59] In China, they have been protected by law since 1989; hunting and trading snow leopards or their body parts constitute a criminal offence that is punishable by the confiscation of property, a fine and a sentence of at least 10 years in prison.[76] They have been protected in Bhutan since 1995.[63]

At the end of 2020, 35 cameras were installed on the outskirts of Almaty, Kazakhstan in hopes to catch footage of snow leopards. In November 2021, it was announced by the Russian World Wildlife Fund (WWF) that snow leopards were spotted 65 times on these cameras in the Trans-Ili Alatau mountains since the cameras were installed.[77][43][78][79][80]

Global Snow Leopard Forum

In 2013, government leaders and officials from all 12 countries encompassing the snow leopard's range (Afghanistan, Bhutan, China, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Nepal, Pakistan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan) came together at the Global Snow Leopard Forum (GSLF) initiated by the then-President of Kyrgyzstan Almazbek Atambayev, and the State Agency on Environmental Protection and Forestry under the government of Kyrgyzstan. The meeting was held in Bishkek, and all countries agreed that the snow leopard and the high mountain habitat need trans-boundary support to ensure a viable future for snow leopard populations, and to safeguard its fragile environment. The event brought together many partners, including NGOs like the Snow Leopard Conservancy, the Snow Leopard Trust, and the Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union. Also supporting the initiative were the Snow Leopard Network, the World Bank's Global Tiger Initiative, the United Nations Development Programme, the World Wild Fund for Nature, the United States Agency for International Development, and Global Environment Facility.[81]

In captivity

The Moscow Zoo exhibited the first captive snow leopard in 1872 that had been caught in Turkestan. In Kyrgyzstan, 420 live snow leopards were caught between 1936 and 1988 and exported to zoos around the world. The Bronx Zoo housed a live snow leopard in 1903; this was the first ever specimen exhibited in a North American zoo.[82] The first captive bred snow leopard cubs were born in the 1990s in the Beijing Zoo.[56] The Snow Leopard Species Survival Plan was initiated in 1984; by 1986, American zoos held 234 individuals.[83][84]

Cultural significance

The snow leopard is widely used in heraldry and as an emblem in Central Asia. The Aq Bars ('White Leopard') is a political symbol of the Tatars, Kazakhs, and Bulgars. A mythical winged Aq Bars is depicted on the national coat of arms of Tatarstan, the seal of the city of Samarqand, Uzbekistan and the old coat of arms of Astana. A snow leopard is depicted on the official seal of Almaty and on the former 10,000 Kazakhstani tenge banknote. In Kyrgyzstan, it is used in highly stylized form in the modern emblem of the capital Bishkek, and the same art has been integrated into the badge of the Kyrgyzstan Girl Scouts Association. It is also considered to be a sacred creature by the Kyrgyz people. A crowned snow leopard features in the arms of Shushensky District in Russia. It is the state animal of Ladakh and Himachal Pradesh in India.[85][86][87][88][89]

The 1978 book The Snow Leopard is an account by Peter Matthiessen about his two-month journey through the Dolpo region of the Nepal Himalayas in search of the snow leopard.[90]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f McCarthy, T.; Mallon, D.; Jackson, R.; Zahler, P. & McCarthy, K. (2017). "Panthera uncia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22732A50664030. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T22732A50664030.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Allen, E. A. (1908). "English Doublets". Publications of the Modern Language Association of America. New Series 16. 23 (1): 184–239. doi:10.2307/456687. JSTOR 456687. S2CID 251028590.

- ^ Liddell, H. G. & Scott, R. (1940). "πάνθηρ". A Greek-English Lexicon (Revised and augmented ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Archived from the original on 2008-04-11. Retrieved 2021-02-21.

- ^ Snow Leopards: Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes. Academic Press. 2016-06-06. ISBN 978-0-12-802496-6. Archived from the original on 2023-11-08. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- ^ Gray, J. E. (1854). "The ounces". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 2. 14: 394.

- ^ Ehrenberg, C. G. (1830). "Observations et données nouvelles sur le tigre du nord et la panthère du nord, recueillies dans le voyage de Sibérie fait par M.A. de Humboldt, en l'année 1829". Annales des sciences naturelles, Zoologie. 21: 387–412.

- ^ Horsfield, T. (1855). "Brief notices of several new or little-known species of Mammalia, lately discovered and collected in Nepal, by Brian Houghton Hodgson". The Annals and Magazine of Natural History: Including Zoology, Botany, and Geology. 2. 16 (92): 101–114. doi:10.1080/037454809495489.

- ^ Sunquist, Mel; Sunquist, Fiona (2017-05-15). Wild Cats of the World. University of Chicago Press. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-226-51823-7. Archived from the original on 2023-11-08. Retrieved 2023-06-25.

- ^ Medvedev, D. G. (2000). "Morfologicheskie otlichiya irbisa iz Yuzhnogo Zabaikalia" [Morphological differences of the snow leopard from Southern Transbaikalia]. Vestnik Irkutskoi Gosudarstvennoi Sel'skokhozyaistvennoi Akademyi [Proceedings of Irkutsk State Agricultural Academy]. 20: 20–30.

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Species Uncia uncia". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 548. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c Johnson, W. E.; Eizirik, E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Murphy, W. J.; Antunes, A.; Teeling, E. & O'Brien, S. J. (2006). "The late Miocene radiation of modern Felidae: a genetic assessment". Science. 311 (5757): 73–77. Bibcode:2006Sci...311...73J. doi:10.1126/science.1122277. PMID 16400146. S2CID 41672825. Archived from the original on 2020-10-04. Retrieved 2018-10-21.

- ^ a b c Davis, B. W.; Li, G. & Murphy, W. J. (2010). "Supermatrix and species tree methods resolve phylogenetic relationships within the big cats, Panthera (Carnivora: Felidae)" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 56 (1): 64–76. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.01.036. PMID 20138224.[dead link]

- ^ Kitchener, A. C.; Driscoll, C. A. & Yamaguchi, N. (2016). "What is a Snow Leopard? Taxonomy, Morphology, and Phylogeny". In McCarthy, T. & Mallon, D. (eds.). Snow Leopards. Amsterdam, Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York: Academic Press. pp. 3–11. ISBN 9780128024966. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ^ Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z. & Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11): 69. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-17. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- ^ Janecka, J. E.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Munkhtsog, B.; Bayaraa, M.; Galsandorj, N.; Wangchuk, T. R.; Karmacharya, D.; Li, J.; Lu, Z. & Uulu, K. Z. (2017). "Range-Wide Snow Leopard Phylogeography Supports Three Subspecies". Journal of Heredity. 108 (6): 597–607. doi:10.1093/jhered/esx044. PMID 28498961.

- ^ Senn, H.; Murray-Dickson, G.; Kitchener, A. C.; Riordan, P. & Mallon, D. (2018). "Response to Janecka et al. 2017". Heredity. 120 (6): 581–585. doi:10.1038/s41437-017-0015-4. PMC 5943311. PMID 29225352.

- ^ Janecka, J. E.; Janecka, M. J.; Helgen, K. M. & Murphy, W. J. (2018). "The validity of three snow leopard subspecies: response to Senn et al". Heredity. 120 (6): 586–590. doi:10.1038/s41437-018-0052-7. PMC 5943360. PMID 29434338.

- ^ Janecka, J. E.; Hacker, C.; Broderick, J.; Pulugulla, S.; Auron, P.; Ringling, M.; Nelson, B.; Munkhtsog, B.; Hussain, S.; Davis, B. & Jackson, R. (2020). "Noninvasive Genetics and Genomics Shed Light on the Status, Phylogeography, and Evolution of the Elusive Snow Leopard". In Ortega, J. & Maldonado, J. E. (eds.). Conservation Genetics in Mammals. Integrative Research Using Novel Approaches. Basel: Springer International Publishing. pp. 83–120. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-33334-8_5. ISBN 978-3-030-33334-8. S2CID 213437425. Archived from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ Korablev, M.; Poyarkov, A. D.; Karnaukhov, A. S.; Zvychaynaya, E. Y.; Kuksin, A. N.; Malykh, S. V.; Istomov, S. V.; Spitsyn, S. V.; Aleksandrov, D. Y.; Hernandez-Blanco, J. A. & Munkhtsog, B. (2021). "Large‑scale and fine‑grain population structure and genetic diversity of snow leopards (Panthera uncia Schreber, 1776) from the northern and western parts of the range with an emphasis on the Russian population" (PDF). Conservation Genetics. 22 (3): 397–410. doi:10.1007/s10592-021-01347-0. S2CID 233480791. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-05-19. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ Hemmer, H. (2023). "An intriguing find of an early Middle Pleistocene European snow leopard, Panthera uncia pyrenaica ssp. nov. (Mammalia, Carnivora, Felidae), from the Arago cave (Tautavel, Pyrénées-Orientales, France)". Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments. 103 (1): 207–220. Bibcode:2023PdPe..103..207H. doi:10.1007/s12549-021-00514-y. S2CID 246433218.

- ^ a b Werdelin, L.; Yamaguchi, N.; Johnson, W. E. & O'Brien, S. J. (2010). "Phylogeny and evolution of cats (Felidae)". In Macdonald, D. W. & Loveridge, A. J. (eds.). Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 59–82. ISBN 978-0-19-923445-5. Archived from the original on 2018-09-25. Retrieved 2018-10-21.

- ^ Mazák, J.H.; Christiansen, P.; Kitchener, A.C. & Goswami, A. (2011). "Oldest known pantherine skull and evolution of the tiger". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): e25483. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...625483M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025483. PMC 3189913. PMID 22016768.

- ^ Tseng, Z. J.; Wang, X.; Slater, G. J.; Takeuchi, G. T.; Li, Q.; Liu, J. & Xie, G. (2014). "Himalayan fossils of the oldest known pantherine establish ancient origin of big cats". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1774): 20132686. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2686. PMC 3843846. PMID 24225466.

- ^ Geraads, D.; Peigné, S (2017). "Re-appraisal of Felis pamiri Ozansoy 1959 (Carnivora, Felidae) from the upper Miocene of Turkey: the earliest pantherine cat?". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 24 (4): 415–425. doi:10.1007/s10914-016-9349-6. S2CID 207195894.

- ^ Hemmer, H. (2023). "The evolution of the palaeopantherine cats, Palaeopanthera gen. nov. blytheae (Tseng et al., 2014) and Palaeopanthera pamiri (Ozansoy, 1959) comb. nov. (Mammalia, Carnivora, Felidae)". Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments. 103: 827–839. doi:10.1007/s12549-023-00571-5. S2CID 257842190.

- ^ Li, G.; Davis, B. W.; Eizirik, E. & Murphy, W. J. (2016). "Phylogenomic evidence for ancient hybridization in the genomes of living cats (Felidae)". Genome Research. 26 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1101/gr.186668.114. PMC 4691742. PMID 26518481.

- ^ a b Hemmer, H. (1972). "Uncia uncia" (PDF). Mammalian Species (20): 1–5. doi:10.2307/3503882. JSTOR 3503882. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-01.

- ^ a b c Nowell, K.; Jackson, P. (1996). "Snow leopard, Uncia uncia". Wild cats: Status survey and conservation action plan. Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. pp. 91–95. ISBN 9782831700458.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sunquist, M. & Sunquist, F. (2002). "Snow leopard Uncia uncia (Schreber, 1775)". Wild Cats of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 377–394. ISBN 978-0-226-77999-7. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ^ Christiansen, P. (2007). "Canine morphology in the larger Felidae: implications for feeding ecology". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 91 (4): 573–592. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2007.00819.x.

- ^ Gish, M. (2016). Snow Leopards. ISBN 978-1-56660-746-9. Archived from the original on 2023-11-08. Retrieved 2023-05-20.

- ^ Pocock, R. I. (1930). "The panthers and ounces of Asia. Part II. The panthers of Kashmir, India, and Ceylon". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 34 (2): 307–336.

- ^ Hast, M. H. (1989). "The larynx of roaring and non-roaring cats". Journal of Anatomy. 163: 117–121. PMC 1256521. PMID 2606766.

- ^ Weissengruber, G. E.; Forstenpointner, G.; Peters, G.; Kübber-Heiss, A.; Fitch, W. T. (2002). "Hyoid apparatus and pharynx in the lion (Panthera leo), jaguar (Panthera onca), tiger (Panthera tigris), cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) and domestic cat (Felis silvestris f. catus)". Journal of Anatomy. 201 (3): 195–209. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00088.x. PMC 1570911. PMID 12363272.

- ^ Torregrosa, V.; Petrucci, M.; Pérez-Claros, J. A. & Palmqvist, P. (2010). "Nasal aperture area and body mass in felids: Ecophysiological implications and paleobiological inferences". Geobios. 43 (6): 653–661. Bibcode:2010Geobi..43..653T. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2010.05.001.

- ^ Janecka, J.E.; Nielsen, S.S.; Andersen, S.D.; Hoffmann, F.G.; Weber, R.E.; Anderson, T.; Storz, J.F. & Fago, A. (2015). "Genetically based low oxygen affinities of felid hemoglobins: lack of biochemical adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia in the snow leopard". Journal of Experimental Biology. 218 (15): 2402–2409. doi:10.1242/jeb.125369. PMC 4528707. PMID 26246610.

- ^ a b McCarthy, T. M. & Chapron, G. (2003). Snow Leopard Survival Strategy (PDF). Seattle, USA: International Snow Leopard Trust and Snow Leopard Network. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-07-11. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- ^ Janečka, J. E.; Jackson. R.; Yuquang, Z.; Diqiang, L.; Munkhtsog, B.; Buckley-Beason, V.; Murphy, W. J. (2008). "Population monitoring of snow leopards using noninvasive collection of scat samples: a pilot study". Animal Conservation. 11 (5): 401–411. Bibcode:2008AnCon..11..401J. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2008.00195.x. S2CID 20787622.

- ^ "Snow leopard census: Ladakh leads the pack with 477, J&K records minimum at 9 of total 718". Greaterkashmir. Archived from the original on 2024-02-01. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ Simms, A.; Moheb, Z.; Salahudin; Ali, H.; Ali, I.; Wood, T. (2011). "Saving threatened species in Afghanistan: snow leopards in the Wakhan Corridor". International Journal of Environmental Studies. 68 (3): 299–312. Bibcode:2011IJEnS..68..299S. doi:10.1080/00207233.2011.577147. S2CID 96170915.

- ^ Jackson, R. & Ahlborn, G. (1988). "Observations on the ecology of snow leopard in west Nepal" (PDF). In Freeman, H. (ed.). Proceedings of the Fifth International Snow Leopard Symposium. India: International Snow Leopard Trust. pp. 65–97. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-07-12. Retrieved 2019-04-09.

- ^ Jackson, R. (1996). Home Range, Movements and Habitat Use of Snow Leopard in Nepal (PhD). London: University of London.

- ^ a b Johansson, Ö.; Rauset, G. R.; Samelius, G.; McCarthy, T.; Andrén, H.; Tumursukh, L. & Mishra, C. (2016). "Land sharing is essential for snow leopard conservation" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 203 (203): 1–7. Bibcode:2016BCons.203....1J. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.08.034. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-05-19. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- ^ Das, S.; Manna, S.; Ray, S.; Das, P.; Rai, U.; Ghosh, B. & Sarkar, M. P. (2019). "Do Urinary Volatiles Carry Communicative Messages in Himalayan Snow Leopards [Panthera uncia, (Schreber, 1775)]?". In Buesching, C. (ed.). Chemical Signals in Vertebrates 14. Vol. 14. Cham: Springer. pp. 27–37. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-17616-7_3. ISBN 978-3-030-17615-0. S2CID 200084900.

- ^ Johansson, Ö.; McCarthy, T.; Samelius, G.; Andrén, H.; Tumursukh, L. & Mishra, C. (2015). "Snow leopard predation in a livestock dominated landscape in Mongolia" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 184: 251–258. Bibcode:2015BCons.184..251J. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2015.02.003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-28. Retrieved 2015-03-25.

- ^ Namgail, T.; Fox, J.L. & Bhatnagar, Y.V. (2007). "Carnivore-caused livestock mortality in Trans-Himalaya" (PDF). Environmental Management. 39 (4): 490–496. doi:10.1007/s00267-005-0178-2. PMID 17318699. S2CID 30967502. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-11-08. Retrieved 2023-10-25.

- ^ Lyngdoh, S.; Shrotriya, S.; Goyal, S. P.; Clements, H.; Hayward, M. W. & Habib, B. (2014). "Prey preferences of the snow leopard (Panthera uncia): regional diet specificity holds global significance for conservation". PLOS ONE. 9 (2): e88349. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...988349L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088349. PMC 3922817. PMID 24533080.

- ^ a b Shehzad, W.; McCarthy, T. M.; Pompanon, F.; Purevjav, L.; Coissac, E.; Riaz, T. & Taberlet, P. (2012). "Prey Preference of Snow Leopard (Panthera uncia) in South Gobi, Mongolia". PLOS ONE. 7 (2): e32104. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...732104S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032104. PMC 3290533. PMID 22393381.

- ^ Khatoon, R.; Hussain, I.; Anwar, M. & Nawaz, M. A. (2017). "Diet selection of snow leopard (Panthera uncia) in Chitral, Pakistan". Turkish Journal of Zoology. 41 (41): 914–923. doi:10.3906/zoo-1604-58.

- ^ Pal, R.; Bhattacharya, T. & Sathyakumar, S. (2020). "Woolly flying squirrel Eupetaurus cinereus: A new addition to the diet of snow leopard Panthera uncia" (PDF). Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 117. doi:10.17087/jbnhs/2020/v117/142056. S2CID 266289402. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ Macri, A. M. & Patterson-Kane, E. (2011). "Behavioural analysis of solitary versus socially housed snow leopards (Panthera uncia), with the provision of simulated social contact". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 130 (3–4): 115–123. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2010.12.005.

- ^ a b Heptner, V. G.; Sludskij, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Snow Leopard, Ounce [Irbis]". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats)]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 276–319.

- ^ Ostrowski, S. & Gilbert, M. (2016). "Diseases of Free-Ranging Snow Leopards and Primary Prey Species". In Nyhus, P.J. (ed.). Snow Leopards. Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes. Amsterdam: Academic Press. pp. 97–112. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-802213-9.00009-2. ISBN 9780128022139.

- ^ Johansson, Ö.; Ausilio, G.; Low, M.; Lkhagvajav, P.; Weckworth, B. & Sharma, K. (2021). "The timing of breeding and independence for snow leopard females and their cubs". Mammalian Biology. 101 (2): 173–180. doi:10.1007/s42991-020-00073-3. S2CID 225114786.

- ^ Pacifici, M.; Santini, L.; Di Marco, M.; Baisero, D.; Francucci, L.; Grottolo Marasini, G.; Visconti, P. & Rondinini, C. (2013). "Generation length for mammals". Nature Conservation (5): 87–94. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2021-12-14.

- ^ a b c Dexel, B. (2002). The Illegal Trade in Snow Leopards – A Global Perspective. Berlin: German Society for Nature Conservation. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.498.7184.

- ^ a b Theile, S. (2003). Fading footprints; the killing and trade of snow leopards (PDF). Cambridge, UK: TRAFFIC International. ISBN 1-85850-201-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-20. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

- ^ Nowell, K.; Li, J.; Paltsyn, M. & Sharma, R.K. (2016). An Ounce of Prevention: Snow Leopard Crime Revisited (PDF). Cambridge, UK: TRAFFIC International. ISBN 978-1-85850-409-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-10. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

- ^ a b Maheshwari, A.; Niraj, S. K.; Sathyakumar, S.; Thakur, M. & Sharma, L. K. (2016). "Snow leopard illegal trade in Afghanistan: A rapid survey". Cat News (64): 22–23.

- ^ Forrest, J. L.; Wikramanayake, E.; Shrestha, R.; Areendran, G.; Gyeltshen, K.; Maheshwari, A.; Mazumdar, S.; Naidoo, R.; Thapa, G. J. & Thapa, K. (2012). "Conservation and climate change: Assessing the vulnerability of snow leopard habitat to treeline shift in the Himalaya" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 150 (1): 129–135. Bibcode:2012BCons.150..129F. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2012.03.001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- ^ "What water means to snow leopards". UNDP. 2 June 2022. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ Moheb, Z. & Paley, R. (2016). "Central Asia: Afghanistan". In McCarthy, T. & Mallon, D. (eds.). Snow Leopards: Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes. Amsterdam, Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York: Academic Press. pp. 409–417. ISBN 9780128024966.

- ^ a b Lham, D.; Thinley, P.; Wangchuk, S.; Wangchuk, N.; Lham, K.; Namgay, T.; Tharchen, L. & Wangchuck, T. (2016). National Snow Leopard Survey of Bhutan – Phase II: Camera Trap Survey for Population Estimation (Report). Thimphu, Bhutan: Wildlife Conservation Division, Department of Forests and Park Services.

- ^ Liu, Y.; Weckworth, B.; Li, J.; Xiao, L.; Zhao, X. & Lu, Z. (2016). "China: The Tibetan Plateau, Sanjiangyuan Region". In McCarthy, T. & Mallon, D. (eds.). Snow Leopards: Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes. Amsterdam, Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York: Academic Press. pp. 513–521. ISBN 9780128024966.

- ^ a b Bhatnagar, Y. V.; Mathur, V. B.; Sathyakumar, S.; Ghoshal, A.; Sharma, R. K.; Bijoor, A.; Raghunath, R.; Timbadia, R. & Lal, P. (2016). "South Asia: India". In McCarthy, T. & Mallon, D. (eds.). Snow Leopards: Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes. Amsterdam, Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York: Academic Press. pp. 457–470. ISBN 9780128024966.

- ^ Loginov, O. (2016). "Central Asia: Kazakhstan". In McCarthy, T.; Mallon, D. (eds.). Snow Leopards: Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes. Amsterdam, Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York: Academic Press. pp. 427–430. ISBN 9780128024966.

- ^ Daveltbakov, A.; Rosen, T.; Anarbaev, M.; Kubanychbekov, Z.; Jumabai uulu, K.; Samanchina, J. & Sharma, K. (2016). "Central Asia: Kyrgyzstan". In McCarthy, T. & Mallon, D. (eds.). Snow Leopards. Amsterdam, Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York: Academic Press. pp. 419–425. ISBN 9780128024966.

- ^ Munkhtsok, B.; Purevjav, L.; McCarthy, T. & Bayrakçismith, R. (2016). "Northern Range: Mongolia". In McCarthy, T. & Mallon, D. (eds.). Snow Leopards. Amsterdam, Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York: Academic Press. pp. 493–500. ISBN 9780128024966.

- ^ Ale, S.; Shah, K. B.; Jackson, R. M. & Rosen, T. (2016). "South Asia: Nepal". In McCarthy, T. & Mallon, D. (eds.). Snow Leopards: Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes. Amsterdam, Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York: Academic Press. pp. 471–479. ISBN 9780128024966.

- ^ Khan, A. (2016). "South Asia: Pakistan". In McCarthy, T.; Mallon, D. (eds.). Snow Leopards: Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes. Amsterdam, Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York: Academic Press. pp. 481–491. ISBN 9780128024966.

- ^ Paltsyn, M.; Poyarkov, A.; Spitsyn, S.; Kuksin, A.; Istomov, S.; Gibbs, J.P.; Jackson, R. M.; Castner, J.; Kozlova, S.; Karnaukhov, A. & Malykh, S. (2016). "Northern Range: Russia". In McCarthy, T. & Mallon, D. (eds.). Snow Leopards: Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes. Amsterdam, Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York: Academic Press. pp. 501–511. ISBN 9780128024966. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ^ Saidov, A.; Karimov, K.; Amirov, Z. & Rosen, T. (2016). "Central Asia: Tajikistan". In McCarthy, T. & Mallon, D. (eds.). Snow Leopards: Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes. Amsterdam, Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York: Academic Press. pp. 433–437. ISBN 9780128024966.

- ^ Esipov, A.; Bykova, E.; Protas, Y. & Aromov, B. (2016). "Central Asia: Uzbekistan". In McCarthy, T. & Mallon, D. (eds.). Snow Leopards: Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes. Amsterdam, Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York: Academic Press. pp. 439–448. ISBN 9780128024966.

- ^ Kattel, B. & Bajiimaya, S. (1995). "Status and conservation of Snow Leopard in Nepal". In Jackson, R. & Ahmad, A. A. (eds.). Proceedings of the Eighth International Snow Leopard Symposium, 12–16 November 1995, Islamabad, Pakistan. Islamabad, Pakistan: International Snow Leopard Trust. pp. 21–27.

- ^ Paltsyn, M.Y.; Spitsyn, S.V.; Kuksin, A.N. & Istomov, S.V. (2012). Snow Leopard Conservation in Russia – Data for Conservation Strategy for Snow Leopard in Russia (Report). Krasnoyarsk: WWF Russia.

- ^ Riordan, P. & Kun, S. (2010). "The Snow Leopard in China". Cat News (Special Issue 5): 14–17.

- ^ Bulatkulova, Saniya (2021-11-21). "Snow Leopards Caught On Camera 65 Times and Counting This Year Alone in Almaty Region". The Astana Times. Archived from the original on 2021-11-23. Retrieved 2024-04-05.

- ^ Esipov, A.; Bykova, E.; Protas, Y. & Aromov, B. (2016). "Central Asia: Uzbekistan". In McCarthy, T. & Mallon, D. (eds.). Snow Leopards. Amsterdam, Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York: Academic Press. pp. 439–447. ISBN 9780128024966. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ^ Jackson, R. (1998). "People-Wildlife Conflict Management in the Qomolangma Nature Preserve, Tibet" (PDF). In Wu Ning; D. Miller; Lhu Zhu; J. Springer (eds.). Tibet's Biodiversity: Conservation and Management. Proceedings of a Conference, August 30 – September 4, 1998. Tibet Forestry Department and World Wide Fund for Nature. pp. 40–46. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ^ Liu, Y.; Weckworth, B.; Li, J.; Xiao, L.; Zhao, X. & Lu, Z. (2016). "China: The Tibetan Plateau, Sanjiangyuan Region". In McCarthy, T. & Mallon, D. (eds.). Snow Leopards. Amsterdam, Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York: Academic Press. pp. 513–521. ISBN 9780128024966. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ^ "Global Snow Leopard Conservation Forum". World Bank. Archived from the original on 2021-04-17. Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- ^ Foderaro, Lisa W. (2013-08-26). "Almost 5 Months Old, Bronx Native Makes Zoo Debut". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2013-08-28. Retrieved 2023-05-15.

- ^ Wharton, D. & Freeman, H. (1988). "The Snow Leopard in North America: Captive Breeding Under the Species Survival Plan". In Freeman, H. (ed.). Proceedings of the Fifth International Snow Leopard Symposium. Seattle and Dehra Dun: International Snow Leopard Trust and Wildlife Institute of India. pp. 131–136.

- ^ McCarthy, Thomas; Mallon, David, eds. (2016-01-01), "Chapter 23 - The Role of Zoos in Snow Leopard Conservation: Captive Snow Leopards as Ambassadors of Wild Kin", Snow Leopards, Academic Press, pp. 311–322, doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-802213-9.00023-7, ISBN 978-0-12-802213-9, archived from the original on 2024-05-05, retrieved 2023-05-15

- ^ Hussain, S. (2019). The Snow Leopard and the Goat: Politics of Conservation in the Western Himalayas. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-74658-6. Archived from the original on 2023-11-08. Retrieved 2023-06-25.

- ^ Cambridge, University of. "Understanding local attitudes to snow leopards vital for their ongoing protection". phys.org. Archived from the original on 2023-05-14. Retrieved 2023-05-27.

- ^ McCarthy, T.; Mallon, D., eds. (2016), "Chapter 15 - Religion and Cultural Impacts on Snow Leopard Conservation", Snow Leopards, Academic Press, pp. 197–217, doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-802213-9.00015-8, ISBN 978-0-12-802213-9, archived from the original on 2021-10-26, retrieved 2023-05-14

- ^ Taub, H. (2018). "The Role of Religion and Spirituality in Snow Leopard Conservation on and Around the Tibetan Plateau". Oregon Undergraduate Research Journal. 12 (1). doi:10.5399/uo/ourj.12.1.3.

- ^ Cambridge, University of. "Understanding local attitudes to snow leopards vital for their ongoing protection". phys.org. Archived from the original on 2023-05-14. Retrieved 2023-05-14.

- ^ Matthiessen, P. (1978). The Snow Leopard. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-65374-8.

Further reading

- Jackson, R.; Hillard, D. (June 1986). "Tracking the Elusive Snow Leopard". National Geographic. Vol. 169, no. 6. pp. 793–809. OCLC 643483454.

- Janczewski, D. N.; Modi, W. S.; Stephens, J. C.; O'Brien, S. J. (July 1995). "Molecular Evolution of Mitochondrial 12S RNA and Cytochrome b Sequences in the Pantherine Lineage of Felidae". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 12 (4): 690–707. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040232. PMID 7544865.

External links

- "The Snow Leopard Network". Snow Leopard Network.

- "Ensuring Snow Leopard survival and conserving mountain landscapes by expanding environmental awareness and sharing innovative practices through community stewardship and partnerships". Snow Leopard Conservancy.

- "Snow Leopard Program". Panthera. Archived from the original on 2015-10-07. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- "Snow Leopard". IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group.

Big cats on the Indian subcontinent | |

|---|---|

| Extant in the wild |

|

| Extirpated from India |

|

| Under reintroduction |

|