A space station is a spacecraft capable of supporting a human crew in orbit for an extended period of time and is therefore a type of space habitat. It lacks major propulsion or landing systems. An orbital station or an orbital space station is an artificial satellite (i.e., a type of orbital spaceflight). Stations must have docking ports to allow other spacecraft to dock to transfer crew and supplies. The purpose of maintaining an orbital outpost varies depending on the program. Space stations have most often been launched for scientific purposes, but military launches have also occurred.

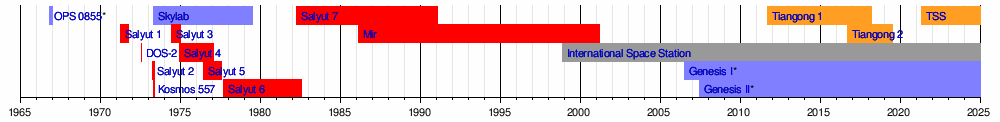

Space stations have harboured so far the only long-duration direct human presence in space. After the first station, Salyut 1 (1971), and the deaths of its Soyuz 11 crew, space stations have been operated consecutively since Skylab (1973), having allowed a progression of long-duration direct human presence in space. Stations have been occupied by consecutive crews since 1987 with the Salyut successor Mir. Uninterrupted occupation of stations has been achieved since the operational transition from the Mir to the ISS, with its first occupation in 2000.

The ISS has hosted the highest number of people in orbit at the same time, reaching 13 for the first time during the eleven day docking of STS-127 in 2009. On May 30, 2023 there were 11 people on the ISS and 6 on China's TSS: with a total of 17 people in orbit, it set the record for most people in orbit as of 2023.[1]

As of 2024, there are two fully operational space stations in low Earth orbit (LEO) – the International Space Station (ISS) and China's Tiangong Space Station (TSS). The ISS has been permanently inhabited since October 2000 with the Expedition 1 crews and the TSS began continuous inhabitation with the Shenzhou 14 crews in June 2022. These stations are used to study the effects of spaceflight on the human body, as well as to provide a location to conduct a greater number and longer length of scientific studies than is possible on other space vehicles. In 2022, the TSS finished its phase 1 construction with the addition of two lab modules: Wentian ("Quest for the Heavens"), launched on 24 July 2022, and Mengtian ("Dreaming of the Heavens") launched on 31 October 2022, joining the ISS as the most recent space station operating in orbit. In July 2022, Russia announced intentions to withdraw from the ISS after 2024 in order to build its own space station.[2] There have been numerous decommissioned space stations, including the USSR's Salyuts and Mir, NASA's Skylab, and China's Tiangong 1 and Tiangong 2.