Rawalpindi

راولپنڈی | |

|---|---|

From top, left to right: Rawal Lake, Gulshan Dadan Khan Mosque, Bahria Town, Rawat Fort, Christ Church, Rawalpindi Railway Station | |

| Nickname: Pindi | |

| Coordinates: 33°36′N 73°02′E / 33.600°N 73.033°E | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Division | Rawalpindi |

| District | Rawalpindi |

| Tehsils | 8 |

| Union councils | 38 |

| Municipal status | 1867[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Metropolitan Corporation |

| • Mayor | None (Vacant) |

| • Deputy Mayor | None (Vacant) |

| • Commissioner | Engineer Abdul Aamir Khattak (BPS-20 PAS)[2] |

| • Deputy Commissioner | Hassan Waqar Cheema (BPS-19 PAS)[3] |

| • Regional Police Officer(RPO) | Syed Khurram Ali (BPS-20 PSP) |

| Area | |

| • City | 479 km2 (185 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 311 km2 (120 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 508 m (1,667 ft) |

| Population | |

| • City | 2,098,231 |

| • Rank | 4th, Pakistan |

| • Density | 4,400/km2 (11,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,098,231 |

| Rawalpindi Metropolitan | |

| Time zone | UTC+05:00 (PKT) |

| • Summer (DST) | PKT |

| Postal code | 46000 |

| Area code | 051 |

| Official Languages | Urdu, English |

| Provincial Language | Punjabi |

| Native Languages | Punjabi |

| Website | Official Website |

Rawalpindi (/rɔːlˈpɪndi/; Punjabi, Urdu: راولپنڈی, romanized: Rāwalpinḍī; pronounced [ɾɑːʋəlpɪnɖiː] [5]) is the third-largest city in the Pakistani province of Punjab. It is a commercial and metropolitan city being the fourth most populous in previous census of 2017 in Pakistan. It is located near the Soan River in north-western Punjab, and is the third-largest Punjabi-speaking city in the world. Rawalpindi is situated close to Pakistan's capital Islamabad, and the two are jointly known as the "twin cities" because of the social and economic links between them.[6]

Located on the Pothohar Plateau of northern Punjab, Rawalpindi remained a small town of little importance up until the 18th century.[7] The Pothohar region is known for its ancient heritage, for instance in the neighbouring city of Taxila, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[8] In 1765, the ruling Gakhars were defeated and the city came under Sukerchakia Misl. During the Sikh-era, Rawalpindi, from a small regional town, became an important city in regards to trade and its strategic location within Punjab. The city's Babu Mohallah neighbourhood was once home to a community of Jewish traders who had fled Mashhad, Persia, in the 1830s.[9]

Punjab was conquered by the East India Company in 1849, in the aftermath of Second Anglo-Sikh War, and in the late 19th century became the largest garrison town of the British Indian Army's Northern command as its climate suited the British authorities.[10][11] The city was established as the headquarters of the Rawalpindi Division of British Punjab, this elevated Rawalpindi to the third largest city in Punjab.[10] Following the partition of British India in 1947, the city became home to the headquarters of the Pakistan Army.[12][13]

In 1951, the Rawalpindi conspiracy took place in which leftist army officers conspired to depose the first elected-prime minister of Pakistan, Liaquat Ali Khan.[14] Rawalpindi later became site of Liaquat Ali Khan's assassination. On 27 December 2007, it was the site of the assassination of former prime minister Benazir Bhutto.[10]

Construction of Pakistan's new purpose-built national capital city of Islamabad in 1961 led to greater investment in the city provided by IMF and local banks,[15] as well as a brief stint as the country's capital before the completion of Islamabad.[16] Modern Rawalpindi is socially and economically intertwined with Islamabad, and the greater metropolitan area. The city is also home to numerous suburban housing developments that serve as bedroom-communities for workers in Islamabad.[17][18] As home to the GHQ of the Pakistan Army and PAF Base Nur Khan, and with connections to the M-1 and M-2 motorways, Rawalpindi is a major logistics and transportation centre for northern Pakistan.[19] The city is also home to historic havelis and temples, and serves as a hub for tourists visiting Rohtas Fort, Azad Kashmir, Taxila and Gilgit-Baltistan.[20][21][22]

The word Rawalpindi consists of two Punjabi words; rawal (راول), and pindi (پنڈی). The origin of the name may derive from the combination of two words: "rawal" meaning "lake" and "pind" meaning "village". The combination of the two words thus means "the village of the lake".[23]

Another theory is that Rawalpindi literally means the “Village of Rawals” as it occupies the site of an old village inhabited by the Rawals, a group of yogis (ascetics).[24] Some accounts propose that a group of yogis arrived in this area with their leader, a head yogi named 'Rawal', and settled here with their followers.

The region around Rawalpindi has been inhabited for thousands of years. Rawalpindi falls within the ancient boundaries of Gandhara, and is thus in a region containing many Buddhist ruins. In the region north-west of Rawalpindi, traces have been found of at least 55 stupas, 28 Buddhist monasteries, 9 temples, and various artifacts in the Kharoshthi script.[25]

To the southeast are the ruins of the Mankiala stupa – a second-century stupa where, according to the Jataka tales, a previous incarnation of the Buddha leapt off a cliff in order to offer his corpse to seven hungry tiger cubs.[27] The nearby town of Taxila is thought to have been home to one of the early universities or education centres of South Asia.[28] Sir Alexander Cunningham identified ruins on the site of the Rawalpindi Cantonment as the ancient city of Ganjipur (or Gajnipur), the capital of the Bhatti tribe in the ages preceding the Christian era.[29]

The first mention of Rawalpindi's earliest settlement dates from when Mahmud of Ghazni destroyed Rawalpindi and the town was restored by Gakhar chief Kai Gohar in the early 11th century. The town fell into decay again after Mongol invasions in the 14th century.[30] Situated along an invasion route, the settlement did not prosper and remained deserted until 1493, when Jhanda Khan Gakhar re-established the ruined town, and named it Rawal.[31]

During the Mughal era, Rawalpindi remained under the rule of the Ghakhar clan, who in turn pledged allegiance to the Mughal Empire. The city was developed as an important outpost in order to guard the frontiers of the Mughal realm.[32] Gakhars fortified a nearby caravanserai, in the 16th century, transforming it into the Rawat Fort in order to defend the Pothohar plateau from Sher Shah Suri's forces.[33] Construction of the Attock Fort in 1581 after Akbar led a campaign against his brother Mirza Muhammad Hakim, further securing Rawalpindi's environs.[29] In December 1585, the Emperor Akbar arrived in Rawalpindi, and remained in and around Rawalpindi for 13 years as he extended the frontiers of the empire,[32] in an era described as a "glorious period" in his career as Emperor.[32]

With the onset of chaos and rivalry between Gakhar chiefs after the death of Kamal Khan in 1559, Rawalpindi was awarded to Said Khan by the Mughal Emperor.[34] Emperor Jehangir visited the royal camp in Rawalpindi in 1622, where he first learned of Shah Abbas I of Persia's plan to invade Kandahar.[35]

Rawalpindi declined in importance as Mughal power declined, until the town was captured in the mid-1760s from Muqarrab Khan by the Sikhs under Sardar Gujjar Singh and his son Sahib Singh.[34] The city's administration was handed to Sardar Milkha Singh, who then invited traders from the neighbouring commercial centers of Jhelum and Shahpur to settle in the territory in 1766.[30][34] The city then began to prosper, although the population in 1770 is estimated to have been only about 300 families.[36] Rawalpindi became for a time the refuge of Shah Shuja, the exiled king of Afghanistan, and of his brother Shah Zaman in the early 19th century.[29]

Sikh ruler Maharaja Ranjit Singh allowed the son of Sardar Milkha Singh to continue as Governor of Rawalpindi, after Ranjit Singh seized the district in 1810.[34] Sikh rule over Rawalpindi was consolidated by defeat of the Afghans at Haidaran in July 1813.[34] The Sikh rulers allied themselves with some of the local Gakhar tribes, and jointly defeated Syed Ahmad Barelvi at Akora Khattak in 1827, and again in 1831 in Balakot.[34] Jews first arrived in Rawalpindi's Babu Mohallah neighbourhood from Mashhad, Persia in 1839,[37] in order to flee from anti-Jewish laws instituted by the Qajar dynasty. In 1841, Diwan Kishan Kaur was appointed Sardar of Rawalpindi.[34]

On 14 March 1849, Sardar Chattar Singh and Raja Sher Singh of the Sikh Empire surrendered to General Gilbert near Rawalpindi, ceding the city to the British.[38] The Sikh Empire then came to an end on 29 March 1849.

Following Rawalpindi's capture by the British East India Company, 53rd Regiment of the company army took quarters in the newly captured city.[29] The decision to man a permanent military cantonment in the city was made in 1851 by the Marquess of Dalhousie.[29]

The city saw its first telegraph office in the early 1850s.[39] The city's Garrison Church was built shortly after in 1854,[29] and is the site where Robert Milman, Bishop of Calcutta, was buried following his death in Rawalpindi in 1876.[29] The city was home to 15,913 people in the 1855 census.[36] During the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny, the area's Gakhars and Janjua tribes remained loyal to the British.[39] Numerous civil and military buildings were built during the British era, and the Municipality of Rawalpindi was constituted in 1867,[29] while the city's population as per the 1868 census was 19,228, with another 9,358 people residing in the city's cantonment.[29]

The city was also connected to railways that offered connection to India and the northwest frontier in Peshawar in the 1880s.[29] The Commissariat Steam Flour Mills were the first such mills in Punjab, and supplied most of the needs of British cantonments throughout Punjab.[29] Rawalpindi's cantonment served as a feeder to other cantonments throughout the region.[29]

Rawalpindi flourished as a commercial centre, though the city remained largely devoid of an industrial base during the British era.[29] A large portion of Kashmir's external trade passing through the city; in 1885, 14% of Kashmir's exports, and 27% of its imports passed through the city.[29] A large market was opened in central Rawalpindi in 1883 by Sardar Sujan Singh, while the British further developed a shopping district for the city's elite known as Saddar with an archway built to commemorate Brigadier General Massey.[29]

Rawalpindi's cantonment became a major centre of military power of the Raj after an arsenal was established in 1883.[30] Britain's army elevated the city from a small town, to the third largest city in Punjab by 1921.[39] In 1868, 9,358 people lived in the city's cantonment – by 1891, the number rose to 37,870.[29] In 1891, the city's population excluding the Cantonment was 34,153.[29] The city was considered to be a favourite first posting for newly arrived soldiers from England, owing to the city's agreeable climate, and the nearby hill station of Murree.[29]

In 1901, Rawalpindi was made the winter headquarters of the Northern Command and of the Rawalpindi military division. Riots broke out against British rule in 1905, following a famine in Punjab that peasants were led to believe was a deliberate act.[40]

During World War I, Rawalpindi District "stood first" among districts in recruiting for the British war effort, with greater financial assistance from the British government channeled into the area in return.[39]

By 1921, Rawalpindi's cantonment had overshadowed the city - Rawalpindi was one of seven cities of Punjab in which over half the population lived in the cantonment district.[39] Communal riots erupted between Rawalpindi's Sikh and Muslim communities in 1926 after Sikhs refused to silence music from a procession that was passing in front of a mosque.[40]

HMS Rawalpindi was launched as an ocean liner in 1925 by Harland and Wolff, the same company which built RMS Titanic. The ship was converted into an armed vessel, and was sunk in October 1939. Scientists from Porton Down carried out poison gas tests on British Indian Army soldiers during the Rawalpindi experiments over the course of more than a decade beginning in the 1930s.[41]

On 5 March 1947, members of Rawalpindi's Hindu and Sikh communities took a procession against the formation of a Muslim ministry within the Government of Punjab. Policemen fired upon protestors, while Hindus and Sikhs fought against weaker Muslim counter-protestors.[42] The area's first Partition riots erupted the next day on 6 March 1947, when the city's Muslims, angered by the actions of Hindus and Sikhs and encouraged by the Pir of Golra Sharif, raided nearby villages after they were unable to do so in the city on account of Rawalpindi's heavily armed Sikhs.[43]

At the dawn of Pakistan's independence in 1947 following the success of the Pakistan Movement, Rawalpindi was 43.79% Muslim, while Rawalpindi District as a whole was 80% Muslim.[44] The region, on account of its large Muslim majority, was thus awarded to Pakistan. Rawalpindi's Hindu and Sikh population, who had made up 33.72% and 17.32% of the city,[44] migrated en masse to the newly independent Dominion of India after anti-Hindu and anti-Sikh pogroms in western Punjab, while Muslim refugees from India settled in the city following anti-Muslim pogroms in eastern Punjab and northern India.[43]

In the years following independence, Rawalpindi saw an influx of Muhajir, Pashtun and Kashmiri settlers. Having been the largest British Cantonment in the region at the dawn of Pakistan's independence, Rawalpindi was chosen as headquarters for the Pakistani Army, despite the fact that Karachi had been selected as the first capital.[14]

In 1951, the Rawalpindi conspiracy took place in which leftist army officers conspired to depose the first elected Prime Minister of Pakistan, Liaquat Ali Khan.[14] Rawalpindi later became the site of the Liaquat Ali Khan's assassination, in what is now known as Liaquat Bagh Park. In 1958, Field Marshal Ayub Khan launched his coup d'etat from Rawalpindi.[14] In 1959, the city became the interim capital of the country under Ayub Khan, who had sought the creation of a new planned capital of Islamabad in the vicinity of Rawalpindi. As a result, Rawalpindi saw most major central government offices and institutions relocate to nearby territory, and its population rapidly expand.

The construction of Pakistan's new capital city of Islamabad in 1961 led to greater investment in Rawalpindi.[16] Rawalpindi remained the headquarters of the Pakistani Army after the capital shifted to Islamabad in 1969, while the Pakistan Air Force continues to maintain an airbase in the Chaklala district of Rawalpindi.[45][46] The military dictatorship of General Zia ul Haq hanged Pakistan's deposed Prime Minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, in Rawalpindi in 1979.[47]

In 1980, tens of thousands of Shia protestors led by Mufti Jaffar Hussain marched to Rawalpindi to protest a provision of Zia ul Haqs Islamization programme.[44] A spate of bombings in September 1987 took place in the city killing 5 people, in attacks that are believed to have been orchestrated by agents of Afghanistan's communist government.[48]

On 10 April 1988, Rawalpindi's Ojhri Camp, an ammunition depot for Afghan mujahideen fighting against Soviet forces in Afghanistan, exploded and killed many in Rawalpindi and Islamabad.[49][50] At the time, the New York Times reported more than 93 were killed and another 1,100 wounded;[51] many believe that the toll was much higher.[52]

Riots erupted in Rawalpindi in 1992 as mobs attacked Hindu temples in retaliation for the destruction of the Babri Masjid in India.[44] On 27 December 2007, Rawalpindi was the site of the assassination of former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto.[53]

Modern Rawalpindi is socially and economically intertwined with Islamabad, and the greater metropolitan area. The city is also home to numerous suburban housing developments that serve as bedroom-communities for workers in Islamabad.[17][18] In June 2015, the Rawalpindi-Islamabad Metrobus, a new bus rapid transit line with various points in Islamabad, opened for service.

|

Main article: Climate of Rawalpindi |

Rawalpindi features a humid subtropical climate (Köppen: Cwa)[54] with hot and wet summers, a cooler and drier winter. Rawalpindi and its twin city Islamabad, during the year experiences an average of 91 thunderstorms, which is the highest frequency of any plain elevation city in the country. Strong windstorms are frequent in the summer during which wind gusts have been reported by Pakistan Meteorological Department to have reached 176 km/h (109 mph). In such thunder/wind storms, which results in some damage of infrastructure.[55] The weather is highly variable due to the proximity of the city to the foothills of Himalayas.

The average annual rainfall is 1,254.8 mm (49.40 in), most of which falls in the summer monsoon season. However, westerly disturbances also bring quite significant rainfall in the winter. In summer, the record maximum temperature has soared to 47.7 °C (118 °F) recorded in June 1954, while it has dropped to a minimum of −3.9 °C (25 °F) several occasions, though the last of which was in January 1967.

| Climate data for Rawalpindi | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 30.1 (86.2) |

30 (86) |

34.5 (94.1) |

40.6 (105.1) |

45.6 (114.1) |

46.6 (115.9) |

44.4 (111.9) |

42 (108) |

38.1 (100.6) |

37.5 (99.5) |

32.2 (90.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

46.6 (115.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 17.9 (64.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

24.5 (76.1) |

30.5 (86.9) |

36 (97) |

38.4 (101.1) |

35.3 (95.5) |

33.7 (92.7) |

33.7 (92.7) |

30.9 (87.6) |

25.9 (78.6) |

20.2 (68.4) |

28.9 (84.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.6 (51.1) |

12.9 (55.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

23.2 (73.8) |

28.4 (83.1) |

31.1 (88.0) |

29.9 (85.8) |

28.8 (83.8) |

27.4 (81.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

17.1 (62.8) |

12.3 (54.1) |

21.8 (71.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.2 (37.8) |

6 (43) |

10.7 (51.3) |

15.8 (60.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

23.7 (74.7) |

24.4 (75.9) |

23.8 (74.8) |

21.1 (70.0) |

14.5 (58.1) |

8.3 (46.9) |

4.3 (39.7) |

14.7 (58.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −3.9 (25.0) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

1.1 (34.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

6.1 (43.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.2 (63.0) |

17.2 (63.0) |

11.6 (52.9) |

5.5 (41.9) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 67.1 (2.64) |

84.1 (3.31) |

92.4 (3.64) |

63.2 (2.49) |

34.1 (1.34) |

75.3 (2.96) |

305.3 (12.02) |

340.3 (13.40) |

110.7 (4.36) |

31.7 (1.25) |

14.4 (0.57) |

36.2 (1.43) |

1,254.8 (49.41) |

| Average precipitation days | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 17 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 78 |

| Source 1: Climate-Data.org, altitude: 497m[54] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: SCBM[56] | |||||||||||||

Social structures in Rawalpindi's historic core centre around neighbourhoods, each known as a Mohallah. Each neighbourhood is served by a nearby bazaar (market) and mosque, which in turn serves as a place where people can gather for trade and manufacturing.[57] Each Mohallah has narrow gallies (streets), and the grouping of houses around short lanes and cul-de-sacs lends a sense of privacy and security to residents of each neighbourhood.[original research?] Major intersections in the neighbourhood are each referred to as a chowk.

Rawalpindi is relatively a new city contrasted with Pakistan's millennia-old cities such as Lahore, Multan, and Peshawar.[58] South of Rawalpindi's historic core, and across the Lai Nullah, are the wide lanes of the Rawalpindi Cantonment. With tree-lined avenues and historic architecture, the cantonment was the main European area developed during British colonial rule. British colonialists also built the Saddar Bazaar south of the historic core, which served as a retail center geared towards Europeans in the city. Beyond the cantonment are the large suburban housing developments that serve as bedroom communities for Islamabad's commuter population.[57]

|

Main article: Demographics of Rawalpindi District |

The population of Rawalpindi is 2,098,231 in 2017. 84% of the population is Punjabi, 9% is Pashtun, and 7% is from other ethnic groups.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1855 | 15,913 | — |

| 1868 | 28,586 | +79.6% |

| 1881 | 52,975 | +85.3% |

| 1891 | 72,023 | +36.0% |

| 1901 | 87,688 | +21.7% |

| 1911 | 86,483 | −1.4% |

| 1921 | 101,142 | +17.0% |

| 1931 | 119,284 | +17.9% |

| 1941 | 185,000 | +55.1% |

| 1951 | 237,000 | +28.1% |

| 1961 | 340,000 | +43.5% |

| 1972 | 615,000 | +80.9% |

| 1981 | 795,000 | +29.3% |

| 1998 | 1,409,768 | +77.3% |

| 2017 | 2,098,231 | +48.8% |

| 2020 | 2,237,000 | +6.6% |

| Source: [59][60][61] | ||

96.7% of Rawalpindi's population is Muslim, 3.1% is Christian, 0.2% belong to other religious groups. The city's Kohaati Bazaar is site of large Shia mourning-processions for Ashura.[62] The neighbourhoods of Waris Shah Mohallah and Pir Harra Mohallah form the core of Muslim settlement in Rawalpindi's old city.

Rawalpindi was a majority Hindu and Sikh city prior to the Partition of India in 1947,[63] combined composing 51.05 percent of the total population according to the 1941 census.[64]: 32 The same census detailed Muslims made up 43.79 percent of the total population.[44][64]: 32 The Baba Dyal Singh Gurdwara in Rawalpindi was where the reformist Nirankari movement of Sikhism originated.[62] The city still has a small Sikh population, but has been bolstered by the arrival of Sikhs fleeing political instability in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.[65]

The city is still home to a few hundred Hindu families.[63] Despite the fact that the vast majority of the city's Hindus fled en masse to India after Partition, most Hindu temples in the old city remain standing, although in disrepair and often abandoned.[63] Many of the old city's neighbourhoods continue to bear Hindu and Sikh names, such as Krishanpura, Arya Mohallah, Akaal Garh, Mohanpura, Amarpura, Kartarpura, Bagh Sardaraan, Angatpura.

The Shri Krishna Mandir is the only functional Hindu temple in Rawalpindi.[66] It was built in the Kabarri Bazaar in 1897.[63] Other temples are abandoned or were repurposed. Rawalpindi's large Kalyan Das Temple from 1880 has been used as the "Gov't. Qandeel Secondary School for the Blind" since 1973.[67][68] The Ram Leela Temple in Kanak Mandi, and the Kaanji Mal Ujagar Mal Ram Richpal Temple in the Kabarri Bazaar, are both currently used to house Kashmiri refugees. Mohan Temple in the Lunda Bazaar remains standing, but is abandoned and the building no longer used for any purpose. The city's "Shamshan Ghat" serves as the city's cremation grounds, and was partly renovated in 2012.[69]

The city's Babu Mohallah neighbourhood was once home to a community of Jewish traders who had fled Mashhad, Persia in the 1830s.[37]

In the British era many churches were built for the British soldiers to come to the churches for Sunday prayer because Rawalpindi Cantonment was the home for the British Army.[37][70]

| Religious group |

1881[71][72][73] | 1891[74]: 68 | 1901[75]: 44 | 1911[76]: 20 | 1921[77]: 23 | 1931[78]: 26 | 1941[64]: 32 | 2017[79] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Islam |

23,664 | 44.67% | 32,787 | 44.43% | 40,807 | 46.54% | 40,678 | 47.04% | 47,653 | 47.11% | 55,637 | 46.64% | 81,038 | 43.79% | 2,029,304 | 96.73% |

| Hinduism |

23,419 | 44.21% | 29,264 | 39.66% | 33,227 | 37.89% | 29,106 | 33.66% | 35,279 | 34.88% | 40,161 | 33.67% | 62,394 | 33.72% | 628 | 0.03% |

| Sikhism |

1,919 | 3.62% | 4,767 | 6.46% | 6,302 | 7.19% | 8,306 | 9.6% | 9,144 | 9.04% | 15,532 | 13.02% | 32,064 | 17.33% | — | — |

| Jainism |

904 | 1.71% | 848 | 1.15% | 1,008 | 1.15% | 963 | 1.11% | 916 | 0.91% | 1,025 | 0.86% | 1,301 | 0.7% | — | — |

| Christianity |

— | — | 6,072 | 8.23% | 6,275 | 7.16% | 7,846 | 9.07% | 8,111 | 8.02% | 6,850 | 5.74% | 3,668 | 1.98% | 65,729 | 3.13% |

| Zoroastrianism |

— | — | 51 | 0.07% | 65 | 0.07% | 58 | 0.07% | 39 | 0.04% | 65 | 0.05% | — | — | — | — |

| Judaism |

— | — | 2 | 0% | — | — | 16 | 0.02% | 0 | 0% | 5 | 0% | — | — | — | — |

| Buddhism |

— | — | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 10 | 0.01% | 0 | 0% | 9 | 0.01% | — | — | — | — |

| Ahmadiyya |

— | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1,848 | 0.09% |

| Others | 3,069 | 5.79% | 4 | 0.01% | 1 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 4,587 | 2.48% | 315 | 0.02% |

| Total population | 52,975 | 100% | 73,795 | 100% | 87,688 | 100% | 86,483 | 100% | 101,142 | 100% | 119,284 | 100% | 185,042 | 100% | 2,097,824 | 100% |

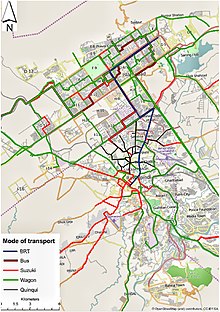

The Rawalpindi-Islamabad Metrobus is a 48.1 km (29.9 mi) bus rapid transit system operating in the Islamabad-Rawalpindi metropolitan area. The Metrobus network's first phase was opened on 4 June 2015, and stretches 22.5 kilometres between Pak Secretariat, in Islamabad, and Saddar in Rawalpindi. The second stage stretches 25.6 kilometres between the Peshawar Morr Interchange and New Islamabad International Airport and was inaugurated on 18 April 2022.[80][81] The system uses e-ticketing and an Intelligent Transportation System and is managed by the Punjab Mass Transit Authority.

Rawalpindi is situated along the historic Grand Trunk Road that connects Peshawar to Islamabad and Lahore. The road is roughly paralleled by the M-1 Motorway between Peshawar and Rawalpindi, while the M-2 Motorway provides an alternate route to Lahore via the Salt Range. The Grand Trunk Road also provides access to the Afghan border via the Khyber Pass, with onwards connections to Kabul and Central Asia via the Salang Pass. The Karakoram Highway provides access between Islamabad and western China, and an alternate route to Central Asia via Kashgar in the Chinese region of Xinjiang.

The Islamabad Expressway connects Rawalpindi's eastern portions with the Rawal Lake and heart of Islamabad. The IJP Road separates Rawalpindi's northern edge from Islamabad.

Rawalpindi is connected to Peshawar by the M-1 Motorway. The motorway also links Rawalpindi to major cities in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, such as Charsadda and Mardan. The M-2 motorway offers high speed access to Lahore via the Potohar Plateau and Salt Range. The M-3 Motorway branches off from the M-2 at the city of Pindi Bhattian, where the M-3 offers onward connections to Faisalabad, and connects to the M-4 Motorway which continues onward to Multan. A new motorway network is under construction to connect Multan and Karachi as part of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor. The Hazara Motorway is also under construction as part of CPEC, and will provide control-access motorway travel all the way to Mansehra via the M-1 or Grand Trunk Road.

Rawalpindi railway station in the Saddar neighbourhood serves as a stop along Pakistan's 1,687 kilometres (1,048 mi)-long Main Line-1 railway that connects the city to the port city of Karachi to Peshawar. The stations is served by the Awam Express, Hazara Express, Islamabad Express, Jaffar Express, Khyber Mail trains, and serves as the terminus for the Margalla Express, Mehr Express, Rawal Express, Pakistan Express, Subak Raftar Express, Green Line Express, Sir Syed Express, Subak Kharam Express and Tezgam trains.

The entire Main Line-1 railway track between Karachi and Peshawar is to be overhauled at a cost of $3.65 billion for the first phase of the project,[82] with completion by 2021.[83] Upgrading of the railway line will permit train travel at speeds of 160 kilometres per hour, versus the average 60 to 105 km per hour speed currently possible on existing track.[84]

Rawalpindi is served by the Islamabad International Airport. The airport is located 21 km west of the city. It offers non-stop flights throughout Pakistan, as well as to the Middle East, Europe, North America, Central Asia, East Asia and Southeast Asia.

The City-District of Rawalpindi is sub-divided into one Municipal Corporation Two Cantonment Board and Seven tehsils:

| Sr. | Tehsil | Headquarters | Area (km2) |

Population (2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Taxila | Taxila | NA | 677,951 |

| 2 | Rawalpindi | Rawalpindi | ? | 2,237,000 |

| 3 | Gujar Khan | Gujar Khan | 1,466 | 678,503 |

| 4 | Kallar Syedan | Kallar Syedan | 421 | 217,273 |

| 5 | Kahuta | Kahuta | NA | 220,576 |

| 6 | Kotli Sattian | Kotli Sattian | NA | 119,312 |

| 7 | Murree | Murree | NA | 233,471 |

Rawalpindi also holds many private colonies that have developed themselves rapidly, e.g. Gulraiz Housing Society, Korang Town, Agochs Town, Ghori Town, Pakistan Town, Judicial Town, Bahria Town[85] which is the Asia's largest private colony, Kashmir Housing Society, Danial Town, Al-Haram City, Education City, Gul Afshan Colony, Allama Iqbal Colony.

Ayub National Park is located beyond the old Presidency on Jhelum Road. It covers an area of about 2,300 acres (930 ha) and has a playland, lake with boating facility, an aquarium and a garden-restaurant. Rawalpindi Public Park is on Murree Road near Shamsabad. The Park was opened to the public in 1991. It has a playland for children, grassy lawns, fountains and flower beds.

In 2008 Jinnah Park was inaugurated at the heart of Rawalpindi and has since become a hotspot of activity for the city. It houses a state-of-the-art cinema, Cinepax,[86] a Metro Cash and Carry supermart, an outlet of McDonald's, gaming lounges, Motion Rides and other recreational facilities. The vast lawns also provide an adequate picnic spot.[87][88]

Rawalpindi is situated near the Ayub National Park formerly known as 'Topi Rakh' (keep the hat on) is by the old Presidency, between the Murree Brewery Co. and Grand Trunk Road. It covers an area of about 2,300 acres (930 ha) and has a play area, lake with boating facility, an aquarium, a garden-restaurant and an open-air theater. This park hosts "The Jungle Kingdom" which is particularly popular among young residents.[89]

|

Main article: Economy of Rawalpindi |

|

Main article: List of educational institutions in Rawalpindi |

Rawalpindi District is home to 2,463 government public schools, out of which 1706 are primary schools, 306 middle schools, 334 are high schools, while 117 are higher education colleges.[91]

97.4% of children ages 6–16 in urban areas of Rawalpindi District are enrolled in school – the third highest percentage in Pakistan after Islamabad and Karachi.[92] 77.1% of Rawalpindi's students in Class 5 are able to read sentences in English.[92] 27% of children in Rawalpindi attend paid private schools.[93]

Rawalpindi, being so close to the capital, has an active media and newspaper climate. There are over a dozen of newspaper companies based in the city including Daily Nawa-i-Waqt, Daily Jang, Daily Asas, The Daily Sada-e-Haq, Daily Express, Daily Din, Daily Aajkal Rawalpindi, Daily Islam, and Daily Pakistan in Urdu and Dawn, Express Tribune, Daily Times, The News International and The Nation in English.

There are a large number of Cable TV service providers in the city such as Nayatel, PTCL, SA Cable Network and DWN. Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation has a centre in Rawalpindi Television channels based in Rawalpindi include:

In mid-2012 3D cinema, The Arena, started its operations in Bahria Town Phase-4 in Rawalpindi.[97][98]