| Xhosa | |

|---|---|

| isiXhosa | |

| Pronunciation | [kǁʰóːsa] |

| Native to | South Africa Lesotho |

| Region | eastern Eastern Cape; scattered communities elsewhere |

| Ethnicity | AmaXhosa |

Native speakers | 8 million (2013)[1] 11 million L2 speakers (2002)[2] |

| Latin (Xhosa alphabet) Xhosa Braille Ditema tsa Dinoko | |

| Signed Xhosa[3] | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | xh |

| ISO 639-2 | xho |

| ISO 639-3 | xho |

| Glottolog | xhos1239 |

S.41[4] | |

| Linguasphere | 99-AUT-fa incl. |

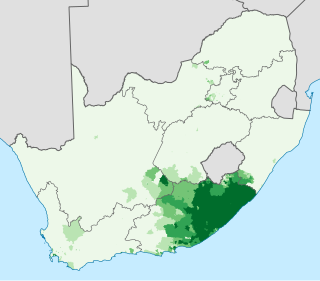

Proportion of the South African population that speaks Xhosa at home

0–20%

20–40%

40–60%

60–80%

80–100% | |

Xhosa (/ˈkɔːsə/ KAW-sə, /ˈkoʊsə/ KOH-sə;[5][6][7] Xhosa pronunciation: [kǁʰóːsa]), formerly spelled Xosa and also known by its local name isiXhosa, is a Nguni language, indigenous to Southern Africa and one of the official languages of South Africa and Zimbabwe.[8] Xhosa is spoken as a first language by approximately 10 million people and as a second language by another 10 million, mostly in South Africa, particularly in Eastern Cape, Western Cape, Northern Cape and Gauteng, and also in parts of Zimbabwe and Lesotho.[9] It has perhaps the heaviest functional load of click consonants in a Bantu language (approximately tied with Yeyi), with one count finding that 10% of basic vocabulary items contained a click.[10]

Classification

[edit]Xhosa is part of the branch of Nguni languages, which also include Zulu, Southern Ndebele and Northern Ndebele, called the Zunda languages.[11] Zunda languages effectively form a dialect continuum of variously mutually intelligible varieties.

Xhosa is, to a large extent, mutually intelligible with Zulu and with other Nguni languages to a lesser extent. Nguni languages are, in turn, classified under the much larger abstraction of Bantu languages.[12]

Geographical distribution

[edit]

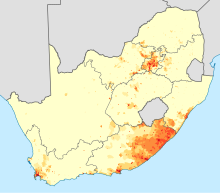

Xhosa is the most widely distributed African language in South Africa, though the most widely spoken African language is Zulu.[12] It is the second most common Bantu home language in South Africa as a whole. As of 2003[update] approximately 5.3 million Xhosa-speakers, the majority, live in the Eastern Cape, followed by the Western Cape (approximately 1 million), Gauteng (671,045), the Free State (246,192), KwaZulu-Natal (219,826), North West (214,461), Mpumalanga (46,553), the Northern Cape (51,228), and Limpopo (14,225).[13] There is a small but significant Xhosa community of about 200,000 in Zimbabwe.[14] Also, a small community of Xhosa speakers (18,000) live in Quthing District, Lesotho.[15]

Orthography

[edit]Latin script

[edit]The Xhosa language employs 26 letters from the Latin alphabet; some of the letters have different pronunciations from English. Phonemes not represented by one of the 26 letters are written as multiple letters. Tone, stress, and vowel length are parts of the language but are generally not indicated in writing.[16]

Phonology

[edit]Vowels

[edit]Xhosa has an inventory of ten vowels: [a], [ɛ~e], [i], [ɔ~o] and [u] written a, e, i, o and u in order, all occurring in both long and short. The /i/ vowel is long in the penultimate syllable and short in the last syllable.[17]

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i ⟨i⟩ | iː ⟨ii⟩ | u ⟨u⟩ | uː ⟨uu⟩ |

| Mid | ɛ ⟨e⟩ | eː ⟨ee⟩ | ɔ ⟨o⟩ | oː ⟨oo⟩ |

| Open | a ⟨a⟩ | aː ⟨aa⟩ | ||

Tones

[edit]Xhosa is a tonal language with two inherent phonemic tones: low and high. Tones are rarely marked in the written language, but they can be indicated ⟨a⟩ [à], ⟨á⟩ [á], ⟨â⟩ [áà], ⟨ä⟩ [àá]. Long vowels are phonemic but are usually not written except for ⟨â⟩ and ⟨ä⟩, which are each sequence of two vowels with different tones that are realized as long vowels with contour tones (⟨â⟩ high–low = falling, ⟨ä⟩ low–high = rising).

Consonants

[edit]Xhosa is rich in uncommon consonants. Besides pulmonic egressive sounds, which are found in all spoken languages, it has a series of ejective stops and one implosive stop.

It has 18 click consonants (in comparison, Juǀʼhoan, spoken in Botswana and Namibia, has 48, and Taa, with roughly 4,000 speakers in Botswana, has 83). There is a series of six dental clicks, represented by the letter ⟨c⟩, similar to the sound represented in English by "tut-tut" or "tsk-tsk"; a series of six alveolar lateral clicks, represented by the letter ⟨x⟩, similar to the sound used to call horses; and a series of alveolar clicks, represented by the letter ⟨q⟩, that sounds somewhat like a cork pulled from a bottle.

The following table lists the consonant phonemes of the language, with the pronunciation in IPA on the left and the orthography on the right:

- Two additional consonants, [r] and [r̤], are found in borrowings. Both are spelled ⟨r⟩.

- Two additional consonants, [ʒ] and [ʒ̈], are found in borrowings. Both are spelled ⟨zh⟩.

- Two additional consonants, [dz] and [dz̤], are found in loans. Both are spelled ⟨dz⟩, as the sound [d̥zʱ].

- An additional consonant, [ŋ̈] is found in loans. It is spelled ⟨ngh⟩.

- The onset cluster /kl/ from phonologized loanwords such as ikliniki "the clinic" can be realized as a single consonant [kʟ̥ʼ].

- The unwritten glottal stop is present in words like uku(ʔ)ayinela "to iron", uku(ʔ)a(ʔ)aza "to stutter", uku(ʔ)amza "to stall".

- In informal writing, this murmured consonant can sometimes be seen spelled as ⟨vh⟩ as in ukuvha, but this is non-standard.

- Sequences of /jw/ as in ukushiywa "abandonment" are phonologically realized [ɥ], but this sound is non-phonemic.

In addition to the ejective affricate [tʃʼ], the spelling ⟨tsh⟩ may also be used for either of the aspirated affricates [tsʰ] and [tʃʰ].

The breathy voiced glottal fricative [ɦ] is sometimes spelled ⟨h⟩.

The ejectives tend to be ejective only in careful pronunciation or in salient positions and, even then, only for some speakers. Otherwise, they tend to be tenuis (plain) stops. Similarly, the tenuis (plain) clicks are often glottalised, with a long voice onset time, but that is uncommon.

The murmured clicks, plosives and affricates are only partially voiced, with the following vowel murmured for some speakers. That is, da may be pronounced [dʱa̤] (or, equivalently, [d̥a̤]). They are better described as slack voiced than as breathy voiced. They are truly voiced only after nasals, but the oral occlusion is then very short in stops, and it usually does not occur at all in clicks. Therefore, the absolute duration of voicing is the same as in tenuis stops. (They may also be voiced between vowels in some speaking styles.) The more notable characteristic is their depressor effect on the tone of the syllable.[20]

Consonant changes with prenasalisation

[edit]When consonants are prenasalised, their pronunciation and spelling may change. The murmur no longer shifts to the following vowel. Fricatives become affricated and, if voiceless, they become ejectives as well: mf is pronounced [ɱp̪fʼ], ndl is pronounced [ndɮ], n+hl becomes ntl [ntɬʼ], n+z becomes ndz [ndz], n+q becomes [n͡ŋǃʼ] etc. The orthographic b in mb is the voiced plosive [mb]. Prenasalisation occurs in several contexts, including on roots with the class 9 prefix /iN-/, for example on an adjective which is feature-matching its noun:

/iN- + ɬɛ/ → [intɬɛ] "beautiful" (of a class 9 word like inja "dog")

When aspirated clicks (⟨ch, xh, qh⟩) are prenasalised, the silent letter ⟨k⟩ is added (⟨nkc, nkx, nkq⟩) to prevent confusion with the nasal clicks ⟨nc, nx, nq⟩, and are actually distinct sounds. The prenasalized versions have a very short voicing at the onset which then releases in an ejective, like the prenasalized affricates, while the phonemically nasal clicks have a very long voicing through the consonant. When plain voiceless clicks (⟨c, x, q⟩) are prenasalized, they become slack voiced nasal (⟨ngc, ngx, ngq⟩).

| Phoneme | Prenasalised | Examples (roots with class 10 /iiN-/ prefix) | Rule |

|---|---|---|---|

| /pʰ/, /tʰ/, /t̠ʲʰ/, /kʰ/, /ǀʰ/, /ǁʰ/, /ǃʰ/ | [mpʼ], [ntʼ], [n̠t̠ʲʼ], [ŋkʼ], [n̪͡ŋǀʼ], [n͡ŋǁʼ], [n̠͡ŋǃʼ] |

|

Aspiration is lost on obstruents; ejection is added on voiceless consonant. |

| /t̠ʲ/ | /n̠d̠ʲ/ |

|

Voiceless palatal plosive becomes voiced. |

| /ǀ/, /ǁ/, /ǃ/ | /ŋǀʱ/, /ŋǁʱ/, /ŋǃʱ/ |

|

Voiced clicks become slack voiced nasal. |

| /kǀʰ/, /kǁʰ/, /kǃʰ/ | /ŋǀʼ/, /ŋǁ'/, /ŋǃ'/ |

|

Aspirated clicks become prenasalized ejective clicks. |

| /ɓ/ | /mb̥ʱ/ |

|

Implosive becomes slack voiced. |

| /f/, /s/, /ʃ/, /ɬ/, /x/ /v/, /z/, /ɮ/, /ɣ/ |

[ɱp̪f], /nts/, /ntʃ/, /ntɬ/, /ŋkx/ [ɱb̪̊vʱ], [nd̥zʱ], [nd̥ɮʱ], [ŋɡ̊ɣʱ]? |

|

Fricatives become affricates. Only phonemic, and thus reflected orthographically, for /nts/, /ntʃ/, /ntɬ/ and /ŋkx/. |

| /m/, /n/, /n̠ʲ/, /ŋ/

/ǀ̃/, /ǁ̃/, /ǃ̃/ |

/m/, /n/, /n̠ʲ/, /ŋ/

/ǀ̃/, /ǁ̃/, /ǃ̃/ |

|

No change when the following consonant is itself a nasal. |

Consonant changes with palatalisation

[edit]Palatalisation is a change that affects labial consonants whenever they are immediately followed by /j/. While palatalisation occurred historically, it is still productive, as is shown by palatalization before the passive suffix /-w/ and before diminutive suffix /-ana/. This process can skip rightwards to non-local syllables (i.e. uku-sebenz-is-el + wa -> ukusetyenziselwa "be used for"), but does not affect morpheme-initial consonants (i.e. uku-bhal+wa -> ukubhalwa "to be written", instead of illicit *ukujalwa). The palatalization process only applies once, as evidenced by ukuphuphumisa+wa -> ukuphuphunyiswa "to be made to overflow", instead of the illicit alternative, *ukuphutshunyiswa.

| Original consonant |

Palatalised consonant |

Examples |

|---|---|---|

| p | tʃ |

|

| pʰ | tʃʰ |

|

| b̥ʱ | d̥ʒʱ |

|

| ɓ | t̠ʲ |

|

| m | n̠ʲ |

|

| mp | ntʃ |

|

| mb̥ʱ | nd̥ʒʱ |

|

Morphology

[edit]In keeping with many other Bantu languages, Xhosa is an agglutinative language, with an array of prefixes and suffixes that are attached to root words. As in other Bantu languages, nouns in Xhosa are classified into morphological classes, or genders (15 in Xhosa), with different prefixes for both singular and plural. Various parts of speech that qualify a noun must agree with the noun according to its gender. Agreements usually reflect part of the original class with which the word agrees. The word order is subject–verb–object, like in English.

The verb is modified by affixes to mark subject, object, tense, aspect and mood. The various parts of the sentence must agree in both class and number.[12]

Nouns

[edit]The Xhosa noun consists of two essential parts, the prefix and the stem. Using the prefixes, nouns can be grouped into noun classes, which are numbered consecutively, to ease comparison with other Bantu languages.

The following table gives an overview of Xhosa noun classes, arranged according to singular-plural pairs.

| Class | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1/2 | um- | aba-, abe- |

| 1a/2a | u- | oo- |

| 3/4 | um- | imi- |

| 5/6 | i-, ili-1 | ama-, ame- |

| 7/8 | is(i)-2 | iz(i)-2 |

| 9/10 | iN-3 | iiN-3, iziN-4 |

| 11/10 | u-, ulu-1, ulw-, ul- | iiN-3, iziN-4 |

| 14 | ubu-, ub-, uty- | |

| 15 | uku- |

1 Before monosyllabic stems, e.g. iliso (eye), uluhlu (list).

2 is- and iz- replace isi- and izi- respectively before stems beginning with a vowel, e.g. isandla/izandla (hand/hands).

3 The placeholder N in the prefixes iN- and iiN- is a nasal consonant which assimilates in place to the following consonant (producing an im- before vowels), but is typically absent in loanwords.

4 Before monosyllabic stems in some words.

Verbs

[edit]Verbs use the following prefixes for the subject and object:

| Person/ Class |

Subject | Object |

|---|---|---|

| 1st sing. | ndi- | -ndi- |

| 2nd sing. | u- | -ku- |

| 1st plur. | si- | -si- |

| 2nd plur. | ni- | -ni- |

| 1 | u- | -m- |

| 2 | ba- | -ba- |

| 3 | u- | -wu- |

| 4 | i- | -yi- |

| 5 | li- | -li- |

| 6 | a- | -wa- |

| 7 | si- | -si- |

| 8 | zi- | -zi- |

| 9 | i- | -yi- |

| 10 | zi- | -zi- |

| 11 | lu- | -lu- |

| 14 | bu- | -bu- |

| 15 | ku- | -ku- |

| reflexive | — | -zi- |

Examples

[edit]- ukudlala – to play

- ukubona – to see

- umntwana – a child

- abantwana – children

- umntwana uyadlala – the child is playing

- abantwana bayadlala – the children are playing

- indoda – a man

- amadoda – men

- indoda iyambona umntwana – the man sees the child

- amadoda ayababona abantwana – the men see the children

Sample phrases and text

[edit]The following is a list of phrases that can be used when one visits a region whose primary language is Xhosa:

| Xhosa | English |

|---|---|

| Molo | Hello |

| Molweni | hello, to a group of people |

| Unjani? | how are you? |

| Ninjani? | How are you?, to a group of people |

| Ndiphilile | I'm okay |

| Siphilile | We're okay |

| Ndiyabulela (kakhulu) | Thank you (a lot) |

| Enkosi (kakhulu) | Thanks (a lot) |

| Ngubani igama lakho? | What is your name? |

| Igama lam ngu.... | My name is.... |

| Ngubani ixesha? | What is the time? |

| Ndingakunceda? | Can I help you? |

| Hamba kakuhle | Goodbye/go well/safe travels |

| Nihamba kakuhle | Goodbye/go well/safe travels

(said to a group of people) |

| Ewe | Yes |

| Hayi | No |

| Andiyazi | I don't know |

| Uyakwazi ukuthetha isiNgesi? | Can you speak English? |

| Ndisaqala ukufunda isiXhosa | I've just started learning Xhosa |

| Uthetha ukuthini? | What do you mean? |

| Ndicela ukuya ngasese? | May I please go to the bathroom? |

| Ndiyakuthanda | I love you |

| Uxolo | Sorry |

| Usapho | Family |

| Thetha | Talk/speak |

History

[edit]

Xhosa-speaking people have inhabited coastal regions of southeastern Africa since before the 16th century. They refer to themselves as the amaXhosa and their language as isiXhosa. Ancestors of the Xhosa migrated to the east coast of Africa and came across Khoisan-speaking people; "as a result of this contact, the Xhosa people borrowed some Khoisan words along with their pronunciation, for instance, the click sounds of the Khoisan languages".[21] The Bantu ancestor of Xhosa did not have clicks, which attests to a strong historical contact with a Khoisan language that did. An estimated 15% of Xhosa vocabulary is of Khoisan origin.[15]

John Bennie was a Scottish Presbyterian missionary and early Xhosa linguist. Bennie, along with John Ross (another missionary), set up a printing press in the Tyhume Valley and the first printed works in Xhosa came out in 1823 from the Lovedale Press in the Alice region of the Eastern Cape. But, as with any language, Xhosa had a rich history of oral traditions from which the society taught, informed, and entertained one another. The first Bible translation was in 1859, produced in part by Henry Hare Dugmore.[15]

Role in modern society

[edit]The role of indigenous languages in South Africa is complex and ambiguous. Their use in education has been governed by legislation, beginning with the Bantu Education Act, 1953.[12]

At present, Xhosa is used as the main language of instruction in many primary schools and some secondary schools, but is largely replaced by English after the early primary grades, even in schools mainly serving Xhosa-speaking communities. The language is also studied as a subject in such schools.

The language of instruction at universities in South Africa is English (or Afrikaans, to a diminishing extent[22]), and Xhosa is taught as a subject, both for native and for non-native speakers.

Literary works, including prose and poetry, are available in Xhosa, as are newspapers and magazines. The South African Broadcasting Corporation broadcasts in Xhosa on both radio (on Umhlobo Wenene FM) and television, and films, plays and music are also produced in the language. The best-known performer of Xhosa songs outside South Africa was Miriam Makeba, whose Click Song #1 (Xhosa Qongqothwane) and "Click Song #2" (Baxabene Ooxam) are known for their large number of click sounds.

In 1996[update], the literacy rate for first-language Xhosa speakers was estimated at 50%.[15]

Anthem

[edit]Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika is part of the national anthem of South Africa, national anthem of Tanzania and Zambia, and the former anthem of Zimbabwe and Namibia. It is a hymn written in Xhosa by Enoch Sontonga in 1897. The single original stanza was:

- Nkosi, sikelel' iAfrika;

- Maluphakanyis' uphondo lwayo;

- Yizwa imithandazo yethu

- Nkosi sikelela, thina lusapho lwayo.

- Lord, bless Africa;

- May her horn rise high up;

- Hear Thou our prayers

- Lord, bless us, its family (, the family of Africa).

Additional stanzas were written later by Sontonga and other writers, and the original verse was translated into Sotho and Afrikaans, as well as English.

In popular culture

[edit]In The Lion King and its reboot, Rafiki the sagely mandrill chants in Xhosa.

In the Marvel Cinematic Universe films Captain America: Civil War, Black Panther, Avengers: Infinity War, Avengers: Endgame, and Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, the language spoken in the fictional African nation of Wakanda is Xhosa. This came about because South African actor John Kani, a native of the Eastern Cape province who plays Wakandan King T'Chaka, speaks Xhosa and suggested that the directors of the fictional Civil War incorporate a dialogue in the language. For Black Panther, director Ryan Coogler "wanted to make it a priority to use Xhosa as much as possible" in the script, and provided dialect coaches for the film's actors.[23]

See also

[edit]- I'solezwe lesiXhosa, the first Xhosa-language newspaper

- U-Carmen eKhayelitsha, a 2005 Xhosa film adaptation of Bizet's Carmen

- Xhosa calendar

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b These are variably tenuis pulmonic to ejective; the ejection tends to be weak even when present. With clicks, only the rear articulation is ejective.

- ^ These are analogous to the slack-voice nasals ⟨mh, nh⟩ etc. They are not prenasalized, as can be seen in words such as ⟨umngqokolo⟩ (overtone singing) and ⟨umngqusho⟩ in which they are preceded by a nasal.

- ^ Incorrectly described as glottal clicks by Nurse, Derek. The Bantu Languages. p. 616. The isiXhosa clicks are not glottalized nasal clicks like those of Nama; they are prenasalized and tenuis/ejective, as maintained by Xhosa linguists like Saul.

References

[edit]- ^ Xhosa at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

- ^ Webb, Vic (2002). Language in South Africa: the role of language in national transformation, reconstruction and development. Impact: Studies in language and society. p. 78. ISBN 978-9-02721-849-0.

- ^ Aarons, Debra & Reynolds, Louise (2003). "South African Sign Language: Changing Policies and Practice". In Leila, Monaghan (ed.). Many Ways to be Deaf: International Variation in Deaf Communities. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press. pp. 194–210. ISBN 978-1-56368-234-6.

- ^ Jouni Filip Maho, 2009. New Updated Guthrie List Online

- ^ "Xhosa – Definition and pronunciation". Oxford Learner's Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ "Xhosa – pronunciation of Xhosa". Macmillan Dictionary. Macmillan Publishers Limited. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ Bauer, Laurie (2007). The Linguistics Student's Handbook. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-74862-759-2.

- ^ "Constitution of Zimbabwe (final draft)" (PDF). Kubatana.net. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2013.

The following languages, namely Chewa, Chibarwe, English, Kalanga, Koisan, Nambya, Ndau, Ndebele, Shangani, Shona, sign language,Venda,Tonga are the officially recognised languages of Zimbabwe.

- ^ "Xhosa alphabet, pronunciation and language". www.omniglot.com. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ^ See Sands, Bonny & Gunnink, Hilde (2019). "Clicks on the fringes of the Kalahari Basin Area". In Clem, Emily; Jenks, Peter & Sande, Hannah (eds.). Theory and Description in African Linguistics: Selected Papers from the 47th Annual Conference on African Linguistics. Berlin: Language Science Press. pp. 703–724. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3365789. ISBN 978-3-96110-205-1.

- ^ Parker, Philip M. (2003). "Xhosa-English Dictionary". Webster's Online Dictionary. Archived from the original on 13 April 2004.

- ^ a b c d "Xhosa". UCLA Language Materials Project. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2006.

- ^ "South Africa Population grows to 44.8 Million". SouthAfrica.info. 9 July 2003. Archived from the original on 22 May 2005.

- ^ Kunju, Hlenze Welsh (2017). Isixhosa Ulwimi Lwabantu Abangesosininzi eZimbabwe: Ukuphila Nokulondolozwa Kwaso [IsiXhosa Indigenous Languages in Zimbabwe: Survival and Preservation] (PhD) (in Xhosa). Rhodes University.

- ^ a b c d "Xhosa". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

((cite web)): CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Thambalwam, lwam (2020). "IsiXhosa". Second Largest Language. 367 (6477): 569–573. doi:10.1126/science.aay8833. ISSN 1095-9203. PMC 9558321. PMID 32001654.

- ^ Branford, William (3 July 2015). The Elements of English: An Introduction to the Principles of the Study of Language. Routledge. pp. 65–. ISBN 978-1-317-42065-1.

- ^ Jessen, Michael (2002). "An Acoustic Study of Contrasting Plosives and Click Accompaniments in Xhosa". Phonetica. 59 (2–3): 150–179. doi:10.1159/000066068. PMID 12232465. S2CID 13216903.

- ^ Saul, Zandisile (2020). Phonemes, Graphemes, and Democracy. Pietermaritzberg, South Africa: University of KwaZulu-Natal. p. 87. ISBN 9781869144388.

- ^ Jessen, Michael; Roux, Justus C. (2002). "Voice quality differences associated with stops and clicks in Xhosa". Journal of Phonetics. 30 (1): 1–52. doi:10.1006/jpho.2001.0150.

- ^ "Xhosa". About World Languages. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ "Afrikaans Phased Out". Language Magazine. 18 April 2019.

- ^ Eligon, John (16 February 2018). "Wakanda Is a Fake Country, but the African Language in 'Black Panther' is Real". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

External links

[edit]- Xhosa language profile (at UCLA Language Materials Project)

- PanAfrican L10n page on Xhosa

- Learn Xhosa

- Xhosa basic lexicon at the Global Lexicostatistical Database

- Paradisec has a collections of Arthur Capell's materials (AC1), which include Xhosa language materials

| Official |

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recognised unofficial languages mentioned in the 1996 constitution |

| ||||||||||||

| Other |

| ||||||||||||

| Official languages | |

|---|---|

| Unofficial languages | |

| Immigrant languages | |