Polychrome is the "practice of decorating architectural elements, sculpture, etc., in a variety of colors."[1] The term is used to refer to certain styles of architecture, pottery, or sculpture in multiple colors.

When looking at artworks and architecture from antiquity and the European Middle Ages, people tend to believe that they were monochrome. In reality, the pre-Renaissance past was full of colour, and all the Greco-Roman sculptures and Gothic cathedrals, that are now white, beige, or grey, were initially painted in bright colours. As André Malraux stated, "Athens was never white but her statues, bereft of color, have conditioned the artistic sensibilities of Europe... the whole past has reached us colorless."[2] Polychrome was and is a practice not limited only to the Western world. Non-Western artworks, like Chinese temples, Oceanian Uli figures, or Maya ceramic vases, were also decorated with colours.

Similarly to the ancient art of other regions, Ancient Near Eastern art was polychrome, bright colours being often present. Many sculptures no longer have their original colouring today, but there are still examples that keep it. One of the best is the Ishtar Gate, the eighth gate to the inner city of Babylon (in the area of present-day Hillah, Babil Governorate, Iraq). It was constructed in c.575 BC by the order of King Nebuchadnezzar II on the north side of the city. It was part of a grand walled processional way leading into the city. Its colours are as rich as they were back in the day because the walls were made of glazed brick.

Many Ancient Near Eastern sculptures were painted too. Although they are grey today, all the Assyrian reliefs that decorated royal palaces were painted in highly saturated colours.

Thanks to the dry climate of Egypt, the original colours of many ancient sculptures in round, reliefs, paintings, and various objects were well preserved. Some of the best preserved examples of ancient Egyptian architecture were the tombs, covered inside with sculpted reliefs painted in bright colours or just frescos. Egyptian artists primarily worked in black, red, yellow, brown, blue, and green pigments. These colours were derived from ground minerals, synthetic materials (Egyptian blue, Egyptian green, and frits used to make glass and ceramic glazes), and carbon-based blacks (soot and charcoal). Most of the minerals were available from local supplies, like iron-oxide pigments (red ochre, yellow ochre, and umber); white derived from the calcium carbonate found in Egypt's extensive limestone hills; and blue and green from azurite and malachite.

Besides their decorative effect, colours were also used for their symbolic associations. Colours on sculptures, coffins, and architecture had both aesthetic and symbolic qualities. Ancient Egyptians saw black as the colour of the fertile alluvial soil, and so associated it with fertility and regeneration. Black was also associated with the afterlife, and was the colour of funerary deities like Anubis. White was the colour of purity, while green and blue were associated with vegetation and rejuvenation. Because of this, Osiris was often shown with green skin, and the faces of coffins from the 26th Dynasty were often green. Red, orange, and yellow were associated with the sun. Red was also the colour of the deserts, and hence associated with Seth and the forces of destruction.[5][6]

Later, during the 19th century, expeditions took place that had the purpose of cataloging the art and culture of ancient Egypt. Description de l'Égypte is a series of early 19th century publications full of illustrations of monuments and artifacts of Ancient Egypt. Most are black-and-white, but some are colourful, so they can show the polychromy from the past. In some cases, only a few traces of paint remained on the walls, pillars and sculptures, but the illustrators attempted successfully at showing the buildings' original state in their pictures.[7]

|

Further information: Ancient Greek art § Polychromy |

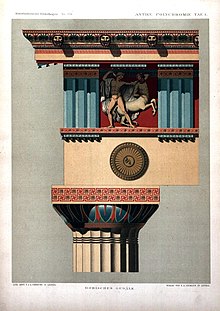

Some very early polychrome pottery has been excavated on Minoan Crete such as at the Bronze Age site of Phaistos.[9] In ancient Greece sculptures were painted in strong colors. The paint was frequently limited to parts depicting clothing, hair, and so on, with the skin left in the natural color of the stone. But it could cover sculptures in their totality. The painting of Greek sculpture should not merely be seen as an enhancement of their sculpted form but has the characteristics of a distinct style of art. For example, the pedimental sculptures from the Temple of Aphaia on Aegina have recently[when?] been demonstrated to have been painted with bold and elaborate patterns, depicting, amongst other details, patterned clothing. The polychrome of stone statues was paralleled by the use of materials to distinguish skin, clothing, and other details in chryselephantine sculptures, and by the use of metals to depict lips, nipples, etc., on high-quality bronzes like the Riace bronzes. The availability of modern digital methods and techniques have allowed the reconstruction and visualization of ancient 3D polychromy in a scientifically sound method and many projects have explored these possibilities in the last years. [10]

An early example of polychrome decoration was found in the Parthenon atop the Acropolis of Athens. By the time European antiquarianism took off in the 18th century, however, the paint that had been on classical buildings had completely weathered off. Thus, the antiquarians' and architects' first impressions of these ruins were that classical beauty was expressed only through shape and composition, lacking in robust colors, and it was that impression which informed neoclassical architecture. However, some classicists such as Jacques Ignace Hittorff noticed traces of paint on classical architecture and this slowly came to be accepted. Such acceptance was later accelerated by observation of minute color traces by microscopic and other means, enabling less tentative reconstructions than Hittorff and his contemporaries had been able to produce. An example of classical Greek architectural polychrome may be seen in the full size replica of the Parthenon exhibited in Nashville, Tennessee, US.

|

See also: Caihua |

Chinese art is known for the use of vibrant colours. Neolithic Chinese ceramic vessels, like those produced by the Yangshao culture, show the use of black and red pigments. Later, tomb and religious sculptures appear as a consequence of the spread of Buddhism. The deities most common in Chinese Buddhist sculpture are forms of the Buddha and the bodhisattva Guanyin. Traces of gold and bright colours in which sculptures were painted still give an idea of their effect. During the Han and Tang dynasties, polychrome ceramic figurines of servants, entertainers, tenants, and soldiers were placed in the tombs of people from upper-class. These figurines were mass-produced in moulds. Although Chinese porcelain is best known as being blue-and-white, many colorful ceramic vases and figures were produced during the Ming and Qing dynasties. During the same two dynasties, cloisonné vessels that use copper wires (cloisons) and bright enamel were also manufactured.

Similarly to what was happening in China, the introduction of Buddhism in Japan in 538 (or perhaps 552 AD) lead to the production of polychrome Japanese Buddhist sculptures. Japanese religious imagery had until then consisted of disposable clay figures used to convey prayers to the spirit world.[19]

Throughout medieval Europe religious sculptures in wood and other media were often brightly painted or colored, as were the interiors of church buildings. These were often destroyed or whitewashed during iconoclast phases of the Protestant Reformation or in other unrest such as the French Revolution, though some have survived in museums such as the V&A, Musée de Cluny, and Louvre. The exteriors of churches were painted as well, but little has survived. Exposure to the elements and changing tastes and religious approval over time acted against their preservation. The "Majesty Portal" of the Collegiate church of Toro is the most extensive remaining example, due to the construction of a chapel which enclosed and protected it from the elements just a century after it was completed.[23]

While stone and metal sculpture normally remained uncolored, like the classical survivals, polychromed wood sculptures were produced by Spanish artists: Juan Martínez Montañés, Gregorio Fernández (17th century); German: Ignaz Günther, Philipp Jakob Straub (18th century); or Brazilian: Aleijadinho (19th century).

Monochromatic color solutions of architectural orders were also designed in the late, dynamic Baroque, drawing on the ideas of Borromini and Guarini. Single-colored stone cladding was used: light sandstone, as in the case of the façade of the Bamberg Jesuit church (Gunzelmann 2016) designed by Georg and Leonhard Dientzenhofer (1686–1693), the façade of the monastery church in Michelsberg by Leonard Dientzenhofer (1696), and the abbey church in Neresheim by J.B. Neumann (1747–1792).[32]

In the space of present-day Germany, during the 18th century, the Asam brothers (Egid Quirin Asam and Cosmas Damian Asam) designed churches with undulating walls, curved borken pediments and polychromy.[33] In the German-speaking space, multiple Rococo churches and libraries with pastel polychrome stuccos and columns were built. There, faux marble columns are made from wood pillars that are covered in a layer of polychrome stucco, a mixture of plaster, lime, and pigment. When these ingredients are mixed, a homogenous-coloured paste is created. To achieve the marble look, thinner batches of darker and lighter paste are made, so that veins begin to appear. It’s all roughly mixed by hand. When the material hardens it's polished by rubbing with fine sandpaper, and thus this layer of polychrome stucco becomes glossy and imitates really realistically marble. A good example of this is the Library of the Wiblingen Abbey in Ulm, Germany. Faux marble made of stucco will continue to be used during the 19th and early 20th centuries too. It is used only for interiors, because stucco dissolves outside through of contact with water.

In Wallachia, during the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the Brâncovenesc style was popular in architecture and decorative arts. It is named after Prince Constantin Brâncoveanu, during whose reign it was developed. Some of the churches in this style have polychrome facades, decorated with murals, like the church of the Stavropoleos Monastery in Bucharest, Romania.

The 2nd half of the 18th century was the rise of Neoclassicism, a movement which tries its best at reviving the styles of Ancient Greece, Rome, the Etruscan civilization, and sometimes even Egypt. During Louis XVI's reign (1760-1789), interiors in the Louis XVI style start to be decorated with arabesques, inspired by those discovered in ancient houses in Pompeii and Herculaneum. They are painted in pastel colours, painted white with the ornate parts gilt, or polychrome. The State Dining Room of the Inveraray Castle in Scotland, decorated by two French painters, is a good example of a polychrome Louis XVI style interior.

With the arrival of European porcelain in the 18th century, brightly colored pottery figurines with a wide range of colors became very popular. Porcelain was developed in China in the 9th century. Its recipe was kept secret from other nations, and only successfully copied in the 15th century by the Japanese and Vietnamese. During the 18th century, German kilns finally figured out how to make porcelain, beginning with the alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger and the physicist Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus, who made the first European variety in 1709. The Meissen Porcelain Factory was founded in the following year, and it became the leading European porcelain manufacturer. Later, other kilns stole the recipe or came up with their own porcelain technology. Another really famous factory was the Sèvres, which produced stunning porcelain for the French elite during the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries.[45]

Compared to the 18th century, polychromy was somewhat more widespread in the 19th. However, the facades of most buildings remained white, most sculptures were unpainted, and most furniture was in the shades of its materials. Colours were added usually though glazed ceramics on buildings, different types of stone on sculptures, and through painting or intarsia most often on furniture. Like in the 18th century, porcelain remained quite colourful, many figures being life-like. In contrast with their exteriors, interiors of many houses of the rich were often decorated with boiserie, stucco, and/or painted. Like in the 2nd half of the 18th century, multiple bronze clocks and decorative objects have two tints through gilding and patina. Porcelain elements were also added for more colour.

Despite evidence of polychrome being discovered on Ancient Greek architecture and sculptures, most Neoclassical buildings have white or beige facades, and black metalwork. Around 1840, the French architect Jacques Ignace Hittorff, published studies of Sicilian architecture, documenting extensive evidence of color. The "polychrome controversy" raged for over a decade and proved to be a challenge for Neoclassical architects throughout Europe.[18]

Due to the discovery of frescos in the Roman cities Pompeii and Herculaneum during the 18th century, multiple 18th and 19th century Neoclassical houses have their interiors decorated with colourful Pompeian style frescos. They often feature bright red, known as "Pompeian red". The fashion for Pompeian styles of painting resulted in rooms finished in vivid blocks of colour. Examples include the Pompeian Room from the Hinxton Hall in Cambridgeshire, the Pompejanum in Aschaffenburg, Empress Joséphine's Bedroom from the Château de Malmaison, and Napoleon's bath of the Château de Rambouillet. By the beginning of the 19th century, painters were also able to create effects of marbling and graining to imitate wood.

"More is more" was the aesthetic principle followed in the Victorian era. Maximalism is present in many types of Victorian era designs, like ceramics, furniture, cutlery, tableware, fashion, architecture, book illustration, clocks, etc. Despite the appetite for ornamentation, many of them remain decorated with only a few colours, especially furniture. Ceramics were the field where polychrome was widespread. Besides objects, polychrome ceramic was also present in architecture and some furniture pieces and architecture through tiles.

The objects and buildings of the 19th century shown in the galleries of this page are without any doubt impressive. Today were are delighted by their ornaments, colours, and styles. However, up to the 1960s, with the rise of Postmodernism, when people started to question Modernism and began to appreciate things from the pre-Modern past, the verdict of Victorian designs wasn't good. During the early 20th century and even when they were made, some described the Victorian age as being one that has been providing us with some of the ugliest objects that have ever been made. Descriptions like 'aesthetic monstrosities' or 'ornamental abominations' were around at the time, and it only got worse. At the end of the 19th century, Marc-Louis Solon (1835-1913), a well established ceramic designer, who worked for Minton and Company, was not unusual in commenting that the period 'bears the stamp of an unmitigated bad taste'.[51] As time passed, negative opinions only got worse. Pioneer Mondern architects Adolf Loos and Le Corbusier felt that works like this were not simply bad, they were such an affront they should have been made illegal.[52]

|

Main article: Polychrome brickwork |

Polychrome brickwork is a style of architectural brickwork which emerged in the 1860s and used bricks of different colours (brown, cream, yellow, red, blue, and black) in patterned combinations to highlight architectural features. These patterns were made around window arches or were just applied on walls. It was often used to replicate the effect of quoining. Early examples featured banding, with later examples exhibiting complex diagonal, criss-cross, and step patterns, in some cases even writing using bricks.[55] Elements of glazed ceramic with details were also used for more complex ornaments.

|

Main article: Romanian Revival architecture |

In the Kingdom of Romania, the Romanian Revival style appeared at the end of the 19th century. It is the Romanian equivalent of the National Romantic style that was popular at the same time in Northern Europe. The movement is heavily inspired by Brâncovenesc architecture, a style that was popular in Wallachia in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Interiors of houses in this style built before WW1 are often decorated with a variety of bright colours. In the case of a few buildings, the polychrome extends on the exterior too, through the use of colorful glazed ceramic tiles. The style became more popular in the 20th century. A Romanian Revival house that stands out through its variety of colours is the Gheorghe Petrașcu House (Piața Romană no. 5) in Bucharest, by Spiru Cegăneanu, 1912[59]

In the twentieth century there were notable periods of polychromy in architecture, from the expressions of Art Nouveau throughout Europe, to the international flourishing of Art Deco or Art Moderne, to the development of postmodernism in the latter decades of the century. During these periods, brickwork, stone, tile, stucco, and metal facades were designed with a focus on the use of new colors and patterns, while architects often looked for inspiration to historical examples ranging from Islamic tilework to English Victorian brick.

At the beginning of the 20th century, before the world wars, Revivalism (including Neoclassicism and the Gothic Revival) and eclecticism of historic styles were very popular in design and architecture. Many of the things said about the 19th century are still in this period. Many of the buildings from this period have their interiors decorated with colours, through tiles, mosaics, stuccos, or murals. When it comes to exteriors, most polychrome facades are decorated with ceramic tiles.

Art Nouveau was also in fashion during the 1900s all over the Western world. However, it fragmented by 1911 and from then it steadily faded, until it disappeared with WW1. Some regular Art Nouveau buildings have their facades decorated with colourful glazed ceramic ornaments. The colours used are often more earthy and faded compared to the intense ones used by Neoclassicism. Compared to other movements in design and architecture, Art Nouveau was one with different versions in multiple countries. The Belgian and French form is characterized by organic shapes, ornaments taken from the plant world, sinuous lines, asymmetry (especially when it comes to objects design), the whiplash motif, the femme fatale, and other elements of nature. In Austria, Germany and the UK, it took a more stylized geometric form, as a form of protest towards revivalism and eclecticism. The geometric ornaments found in Gustav Klimt's paintings and in the furniture of Koloman Moser are representative of the Vienna Secession (Austrian Art Nouveau). In some countries, artists found inspiration in national tradition and folklore. In the UK for example, multiple silversmiths used interlaces taken from Celtic art. Similarly, Hungarian, Russian, and Ukrainian architects used polychromatic folkloric motifs on their buildings, usually through colourful ceramic ornaments.

During the interwar period and the middle of the 20th century, Modernism was in fashion. To Modernists, form was more important than ornament, so solid blocks of strong colour were often used to emphasize shape and create contrast. Primary colours and black and white were preferred. This is really the case of the Dutch De Stijl movement, which began in 1917. The style involved reducing an object (whether a painting or a design) to its essentials, using only black, white and primary colours, and a simple geometry of straight lines and planes. Gerrit Rietveld's Red and Blue Chair (1917-1918) and Rietveld Schröder House in Utrecht (1924) show this use of colour. Polychromy in Modernist design was not limited to De Stijl. The Unité d'habitation, a residential housing typology developed by Le Corbusier, has some flat colourful parts.

Some Art Deco objects, buildings and interiors stand out through their polychromy and use of intense colours. Fauvism, with its highly saturated colours, like the paintings of Henri Matisse, was an influence for some Art Deco designers. Another influence for polychromy were the Ballets Russes. Leon Bakst's stage designs filled Parisian artistic circles with enthusiasm for bright colours.[72]

Despite their lack of ornamentation, multiple Mid-century modern designs, like Lucienne Day's textiles, Charles and Ray Eames's Hang-It-All coat hanger (1953), or Irving Harper's Marshmallow sofa (1956), are decorated with colours. Aside from individual objects, mid-century modern interiors were also quite colourful. This was also caused by the fact that after WW2, plastics became increasingly popular as a material for kitchenware and kitchen units, light fixtures, electrical appliances and toys, and by the fact that plastic could be produced in a wide range of colours, from jade green to red.[73]

The use of vivid colours continued with Postmodernism, in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. Compared to Mid-century modern objects, which often had intense colours but were monochrome, Postmodern design and architecture stand out through the use of a variety of colours on single objects or buildings. Postmodern architects working with bold colors included Robert Venturi (Allen Memorial Art Museum addition; Best Company Warehouse), Michael Graves (Snyderman House; Humana Building), and James Stirling (Neue Staatsgalerie; Arthur M. Sackler Museum), among others. In the UK, John Outram created numerous bright and colourful buildings throughout the 1980s and 90s, including the "Temple of Storms" pumping station. Aside from architecture, bright colours were present on everything, from furniture to textiles and posters. Neon greens and yellows were popular in product design, as were fluorescent tones of scarlet, pink, and orange used together. Injection-moulded plastics gave designers new creative freedom, making it possible to mass produce almost any shape (and colour) quickly and cheaply.[82]

An artist well known for her polychrome artworks is Niki de Saint Phalle, who produced many sculptures painted in bold colours. She devoted the later decades of her life to building a live-in sculpture park in Tuscany, the Tarot Garden, with artworks covered in vibrant colourful mosaics.[83]

Polychrome building facades later rose in popularity as a way of highlighting certain trim features in Victorian and Queen Anne architecture in the United States. The rise of the modern paint industry following the American Civil War also helped to fuel the (sometimes extravagant) use of multiple colors.

The polychrome facade style faded with the rise of the 20th century's revival movements, which stressed classical colors applied in restrained fashion and, more importantly, with the birth of modernism, which advocated clean, unornamented facades rendered in white stucco or paint. Polychromy reappeared with the flourishing of the preservation movement and its embrace of (what had previously been seen as) the excesses of the Victorian era and in San Francisco, California in the 1970s to describe its abundant late-nineteenth-century houses. These earned the endearment 'Painted Ladies', a term that in modern times is considered kitsch when it is applied to describe all Victorian houses that have been painted with period colors.

John Joseph Earley (1881–1945) developed a "polychrome" process of concrete slab construction and ornamentation that was admired across America. In the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area, his products graced a variety of buildings — all formed by the staff of the Earley Studio in Rosslyn, Virginia. Earley's Polychrome Historic District houses in Silver Spring, Maryland were built in the mid-1930s. The concrete panels were pre-cast with colorful stones and shipped to the lot for on-site assembly. Earley wanted to develop a higher standard of affordable housing after the Depression, but only a handful of the houses were built before he died; written records of his concrete casting techniques were destroyed in a fire. Less well-known, but just as impressive, is the Dr. Fealy Polychrome House that Earley built atop a hill in Southeast Washington, D.C. overlooking the city. His uniquely designed polychrome houses were outstanding among prefabricated houses in the country, appreciated for their Art Deco ornament and superb craftsmanship.

Native American ceramic artists, in particular those in the Southwest, produced polychrome pottery from the time of the Mogollon cultures and Mimbres peoples to contemporary times.[93]

In the 2000s, the art of designing art toys was taking off. Multiple monochrome or polychrome vinyl figurines were produced during this period, and are still produced during the 2020s. A few artists who designed vinyl toys include Joe Ledbetter, Takashi Murakami, Flying Förtress, and CoonOne1.

During the 2010s and the early 2020s, a new interest for Postmodern architecture and design appeared. One of the causes were memorial exhibitions that presented the style, the most comprehensive and influential one being held at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London in 2011, called Postmodernism: Style and Subversion, 1975-1990. The Salone del Mobile in Milan since 2014 showcased revivals, reinterpretations, and new postmodern-influenced designs.[94] Because of this, multiple funky polychrome buildings were erected, like the House for Essex, Wrabness, Essex, the UK, by FAT and Grayson Perry, 2014[95] or the Miami Museum Garage, Miami, USA, by WORKac, 2018.[96]

Besides revivals of Postmodernism, another key design movement of the early 2020s is Maximalism. Since its philosophy can be summarized as "more is more", contrasting with the minimalist motto "less is more", it is characterized by a wide use of intense colours and patterns.

The term polychromatic means having several colors. It is used to describe light that exhibits more than one color, which also means that it contains radiation of more than one wavelength. The study of polychromatics is particularly useful in the production of diffraction gratings.