Σελινοῦς | |

The Temple of Hera at Selinunte (Temple E) | |

| Location | Marinella di Selinunte, Province of Trapani, Sicily, Italy |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°35′1″N 12°49′29″E / 37.58361°N 12.82472°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 270 ha (670 acres) |

| History | |

| Founded | 628 BC |

| Abandoned | Approximately 250 BC |

| Periods | Archaic Greece to Hellenistic period |

| Site notes | |

| Management | Soprintendenza BB.CC.AA. di Trapani |

| Website | Parco Archeologico di Selinunte (in Italian) |

Selinunte (/ˌsɛlɪˈnuːnteɪ/ SEL-in-OON-tay, Italian: [seliˈnunte]; Ancient Greek: Σελῑνοῦς, romanized: Selīnoûs [seliːnûːs]; Latin: Selīnūs [sɛˈliːnuːs]; Sicilian: Silinunti [sɪlɪˈnuntɪ]) was a rich and extensive ancient Greek city of Magna Graecia on the south-western coast of Sicily in Italy. It was situated between the valleys of the Cottone and Modione rivers. It now lies in the comune of Castelvetrano, between the frazioni of Triscina di Selinunte in the west and Marinella di Selinunte in the east.

The archaeological site contains many great temples, the earliest dating from 550 BC, with five centred on an acropolis.

At its peak before 409 BC the city may have had 30,000 inhabitants, excluding slaves.[1] It was destroyed and abandoned in 250 BC and never reoccupied.

History

[edit]

Selinunte was one of the most important of the Greek colonies in Sicily, situated on the southwest coast of that island, at the mouth of the small river of the same name, and 6.5 km west of the Hypsas river (the modern Belice). It was founded, according to the historian Thucydides, by a colony from the Sicilian city of Megara Hyblaea, under the leadership of a man called Pammilus, about 100 years after the foundation of Megara Hyblaea, with the help of colonists from Megara in Greece, which was Megara Hyblaea's mother city.[2] The date of its foundation cannot be precisely fixed, as Thucydides indicates it only by reference to the foundation of Megara Hyblaea, which is itself not accurately known, but it may be placed about 628 BC. Diodorus places it 22 years earlier, or 650 BC, and Hieronymus still further back in 654 BC. The date from Thucydides, which is probably the most likely, is incompatible with this earlier date.[3] The name is supposed to have been derived from quantities of wild celery (Ancient Greek: σέλινον, romanized: (selinon))[4] that grew on the spot. For the same reason, they adopted the celery leaf as the symbol on their coins.

Selinunte was the most westerly of the Greek colonies in Sicily, and for this reason they soon came into contact with the Phoenicians of western Sicily and the native Sicilians in the west and northwest of the island. The Phoenicians do not at first seem to have conflicted with them; but as early as 580 BC the Selinuntines were engaged in hostilities with the non-Greek Elymian people of Segesta, whose territory bordered their own.[5] A body of emigrants from Rhodes and Cnidus who subsequently founded Lipara, supported the Segestans on this occasion, leading to their victory; but disputes and hostilities between the Segestans and Selinuntines seem to have occurred frequently, and it is possible that when Diodorus speaks of the Segestans being at war with the Lilybaeans (modern Marsala) in 454 BC,[6] that the Selinuntines are the people really meant.

The river Mazarus, which at that time appears to have formed the boundary with Segesta, was only about 25 km west of Selinunte; and it is certain that at a somewhat later period the territory of Selinunte extended to its banks, and that that city had a fort and emporium at its mouth.[7] On the other side Selinunte's territory certainly extended as far as the Halycus (modern Platani), at the mouth of which it founded the colony of Minoa, or Heracleia, as it was afterward called.[8] It is clear, therefore, that Selinunte had already achieved great power and prosperity; but very little information survives about its history. Like most of the Sicilian cities, it passed from an oligarchy to a tyranny, and about 510 BC was subject to a despot named Peithagoras, who was overthrown with the assistance of the Spartan Euryleon, one of the companions of Dorieus. Euryleon himself ruled the city, for a little while, but was speedily overthrown and put to death by the Selinuntines.[9] The Selinuntines supported the Carthaginians during the great expedition of Hamilcar (480 BC); they even promised to send a contingent to the Carthaginian army, but this did not arrive until after Hamilcar's defeat at the Battle of Himera.[10]

The Selinuntines are next mentioned in 466 BC, co-operating with the other cities of Sicily to help the Syracusans to expel Thrasybulus.[11] Thucydides speaks of Selinunte just before the Athenian expedition in 416 BC as a powerful and wealthy city, possessing great resources for war both by land and sea, and having large stores of wealth accumulated in its temples.[12] Diodorus also represents it at the time of the Carthaginian invasion, as having enjoyed a long period of tranquility, and possessing a numerous population.[13] The walls of Selinunte enclosed an area of approximately 100 hectares (250 acres).[14] The population of the city has been estimated at 14,000 to 19,000 people during the fifth century BC.[15]

The Sicilian Expedition

[edit]In 416 BC, a renewal of the earlier disputes between Selinunte and Segesta led to the great Athenian expedition to Sicily. The Selinuntines called on Syracuse for assistance, and were able to blockade the Segestans; but the Segestans appealed to Athens for help.[16] The Athenians do not appear to have taken any immediate action to save Segesta, but no further conflict around Segesta is recorded. When the Athenian expedition first arrived in Sicily (415 BC), Thucydides presents the general Nicias as proposing that the Athenians should proceed to Selinunte at once and compel the Selinuntines to surrender on moderate terms;[17] but this advice was overruled and the expedition sailed against Syracuse instead. As a result, the Selinuntines played only a minor part in the subsequent operations. They are, however, mentioned on several occasions providing troops to the Syracusans; and it was at Selinunte that the large Peloponnesian force sent to support Gylippus landed in the spring of 413 BC, having been driven over to the coast of Africa by a tempest.[18]

Captured by Carthage

[edit]The defeat of the Athenian armament apparently left the Segestans at the mercy of their rivals. They surrendered the frontier district that was the original subject of dispute to Selinunte. The Selinuntines, however, were not satisfied with this concession, and continued their hostility against them, leading the Segestans to seek assistance from Carthage. After some hesitation, Carthage sent a small force, with the assistance of which the Segestans defeated the Selinuntines in a battle.[19] The Carthaginians in the following spring (409 BC) sent over a vast army containing 100,000 men, according to the lowest ancient estimate, led by Hannibal Mago (the grandson of Hamilcar that was killed at Himera). The army landed at Lilybaeum, and directly marched from there to Selinunte. The city's inhabitants had not expected such a force and were wholly unprepared to resist it. The city fortifications were, in many places, in disrepair, and the armed forces promised by Syracuse, Acragas (modern Agrigento) and Gela, were not ready and did not arrive in time. The Selinuntines fought the Carthaginians on their own and continued to defend their individual houses even after the walls were breached. However, the enemy's overwhelming numbers made resistance hopeless, and after a ten-day siege the city was taken and most of the defenders put to death. According to sources, 16,000 of the citizens of Selinunte were killed, 5,000 were taken prisoner, and 2,600 under the command of Empedion escaped to Acragas.[20][21] Subsequently, a considerable number of the survivors and fugitives were gathered together by Hermocrates of Syracuse, and established within the walls of the city.[22] Shortly after, Hannibal destroyed the city walls, but gave permission to the surviving inhabitants to return and occupy it as tributaries of Carthage. A considerable part of the citizens of Selinunte took up this offer, which was confirmed by the treaty subsequently concluded between Dionysius, tyrant of Syracuse, and the Carthaginians, in 405 BC.[21]

Destruction

[edit]The Selinuntines are again mentioned in 397 BC when they supported Dionysius during his war with Carthage;[23] but both the city and territory were again given up to the Carthaginians by the peace of 383 BC.[24] Although Dionysius reconquered it shortly before his death,[25] it soon returned to Carthaginian control. The Halycus River, which was established as the eastern boundary of the Carthaginian dominion in Sicily by the treaty of 383 BC, seems to have generally continued to have been the border, despite temporary interruptions; and was again fixed as the border by the treaty with Agathocles in 314 BC.[26] This last treaty expressly stipulated that Selinunte, as well as Heracleia and Himera, were subjects of Carthage, as before. In 276 BC, however, during the expedition of Pyrrhus to Sicily, the Selinuntines voluntarily joined Pyrrhus, after the capture of Heracleia.[27] By the First Punic War, Selinunte was again under Carthaginian control, and its territory was repeatedly the theater of military operations between the Romans and the Carthaginians.[28] But before the close of the war (about 250 BC), when the Carthaginians were beginning to pull back, and confine themselves to the defense of as few places as possible, they removed all the inhabitants of Selinunte to Lilybaeum and destroyed the city.[29]

It seems that it was never rebuilt. Pliny the Elder mentions its name (Selinus oppidum[30]), as if it still existed as a town in his time, but Strabo distinctly classes it with extinct cities. Ptolemy, though he mentions the river Selinus, does not mention a town of the name.[31] The Thermae Selinuntiae (at modern Sciacca), which derived their name from the ancient city, and seem to have been much frequented in the time of the Romans, were situated at a considerable distance, 30 km, from Selinunte: they are sulfurous springs, still much valued for their medical properties, and dedicated, like most thermal waters in Sicily, to San Calogero. At a later period they were called the Aquae Labodes or Larodes, under which name they appear in the Itineraries.[32]

Archaeological remains

[edit]

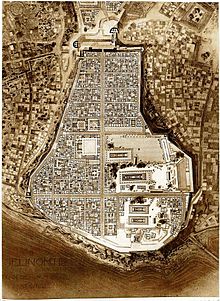

The city is beside the sea, between the Modione River (the ancient Selinus) in the west and the Cottone River in the east, on two high areas connected by a narrow isthmus. The part of the city to the south, next to the sea, contains the acropolis which is based around two intersecting streets and contains many temples (A, B, C, D, O). The part of the city on the Mannuzza Hill to the north, further inland, contained housing on the Hippodamian plan contemporary with the acropolis and two necropoleis (Galera-Bagliazzo and Manuzza).

Other important remains are found on the high places across the rivers to the east and west of the city. In the east there are three temples (E, F, G) and a necropolis (Buffa) north of the modern village of Marinella. In the west are the most ancient remains of Selinus: the Sanctuary of the Malophoros and the archaic necropolis (Pipio, Manicalunga, Timpone Nero). The two ports of the city were in the mouths of the city's two rivers.

The modern Archaeological park, which covers about 270 hectares can therefore be divided into the following areas:[33]

- The Acropolis at the centre with temples and fortifications

- Gaggera Hill in the West, with the sanctuary of Malophoros

- Mannuzza Hill in the north with ancient housing

- The East Hill in the east, with other temples

- The necropoleis

The Acropolis

[edit]

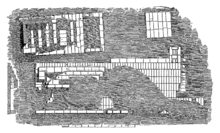

The acropolis is on a limestone massif with a cliff face falling into the sea in the south, while the north end narrows to 140 m wide. The settlement was in the form of a massive trapezoid, extended to the north with a large retaining wall in terraces (about eleven metres high) and surrounded by a wall (repeatedly restored and modified) with an exterior of squared stone blocks and an interior of rough stone (emplecton). It had five towers and four gates. To the north, the acropolis was fortified by a counter wall and towers from the beginning of the fourth century BC.

At the entrance to the acropolis is the so-called Tower of Pollux, constructed in the sixteenth century to deter the Barbary pirates, atop the remains of an ancient tower or lighthouse.

The Hippodamian urban plan dates to the fourth century BC (i.e. to the period of Punic rule) and is divided in quarters by two main streets (9 metres wide), which cross at right angles (the North-South road is 425 metres long, the East-West is 338 metres long). Every 32 metres they are intersected by other minor roads (5 metres wide).

On the crest of the acropolis are the remains of numerous Doric temples.[33]

Multiple altars and little sanctuaries may be attributed to the first years of the colony, which were replaced around fifty years later by large, more permanent temples. The first of these is the so-called Megaron near Temples B & C. In front of Temple O there is a Punic sacrificial area from after the conquest of 409 BC, consisting of rooms built of dry masonry within which vases containing ashes were deposited along with amphorae of the Carthaginian “torpedo” type.

Temple O and Temple A of which little remains except for the rocky basement and the altar which was constructed between 490 and 460 BC. They had nearly identical structures, similar to that of Temple E on the East Hill. The peristyle was 16.2 x 40.2 m with 6 x 14 columns (6.23 metres high). Inside there was a pronaos in antis, a naos with an adyton and an opisthodomos in antis, separate from the naos. The naos was a step higher than the pronaos and the adyton was a step higher again. In the wall between the pronaos and the naos in Temple A two spiral staircases led to the gallery (or floor) above. The pronaos of Temple A has a mosaic pavement showing symbolic figures of the Phoenician goddess Tanit, a caduceus, the Sun, a crown, and a bull's head, which testifies to the reuse of the space as a religious or domestic area in the Punic period. Temple O was dedicated to Poseidon or perhaps Athena;[34] Temple A to the Dioscuri or perhaps to Apollo.[34]

34 metres east of Temple A are the remains of the monumental entrance to the area, which took the form of a propylaea with a floorplan in the shape of a T, made up of a 13 x 5.6 metre rectangle with a peristyle of 5 x 12 columns and another rectangle of 6.78 x 7.25 metres.

Across the East-West street there is a second sacred area, north of the preceding. There, to the south of Temple C is a Shrine 17.65 metres long and 5.5 metres wide which dates from 580 to 570 BC and has the archaic form of the Megaron, perhaps intended to hold votive offerings. Lacking a pronaos, the entrance at the eastern end passed directly into the naos (at the centre of which there are two bases for the wooden columns which held up the roof). At the back there was a square adyton, to which a third space was added in a later period. The Shrine was perhaps dedicated to Demeter Thesmophoros.[35]

To the right of the shrine is Temple B from the Hellenistic period, which is small (8.4 x 4.6 metres) and in bad condition. It is made up of a prostyle portico of four columns which is reached by a stairway with nine steps, followed by a pronaos and naos. In 1824 clear traces of polychrome stucco were still visible. Probably constructed around 250 BC, a short time before Selinus was abandoned for good, it represents the only religious building that attests to the modest revival of the city after its destruction in 409. Its purpose remains obscure; in the past it was believed to be the Heroon of Empedocles, benefactor of the Selinuntine marshes,[36] but this theory is no longer sustainable, given the building's date. Today it is thought more likely to be a strongly Hellenised Punic cult, perhaps to Demeter or Asclepius-Eshmun.

Temple C is the oldest in this area, dating from 550 BC. In 1925-7 the fourteen of the north side's seventeen columns were re-erected, along with part of the entablature. It had a peristyle (24 x 63.7 metres) of 6 x 17 columns (8.62 metres high). The entrance is reached by eight steps and consists of a portico with a second row of columns and then the pronaos. Behind it is the naos and adyton in a single long narrow structure (an archaic characteristic). It has basically the same floor plan as Temple F on the East Hill. Multiple elements show a certain experimentation and divergence from the pattern of the Doric temple which later became the standard: the columns are squat and massive (some are even made from a single stone), lack entasis, show variation in the number of flutes, the width of the intercolumniation varies, the corner columns have a larger diameter than the others, etc. Finds in the temple include: some fragments of red, brown, and purple polychrome terracotta from the cornice decoration, a gigantic 2.5-metre-high (8.2 ft) clay gorgon head from the pediment, three metopes representing Perseus slaying the Gorgon, Heracles with the Cercopes, and a frontal view of the quadriga of Apollo, all of which are in the Museo Archeologico di Palermo. Temple C probably functioned as an archive, since hundreds of seals have been found here and was dedicated to Apollo, according to epigraphic evidence,[37] or perhaps Heracles.[38] British architects Samuel Angell and William Harris excavated at Selinus in the course of their tour of Sicily, and came upon the sculptured metopes from the Archaic temple of “Temple C.” Although local Bourbon officials tried to stop them, they continued their work, and attempted to export their finds to England, destined for the British Museum. Now in the echoes of the activities of Lord Elgin in Athens, Angell and Harris’s shipments were diverted to Palermo by force of the Bourbon authorities and are now kept in the Palermo archeological museum.[39]

East of Temple C is its rectangular grand altar (20.4 metres long x 8 metres wide) of which the foundations and some steps remain. After that there is the area of the Hellenistic agora. A little further there are the remains of houses and the terrace is bordered by a Doric portico (57 metres long and 2.8 metres deep) which overlooks part of the wall supporting the acropolis.

Next is Temple D which is dated to 540 BC. The west face fronts directly onto the north-south street. The peristyle is 24 metres × 56 metres on a 6 × 13 column pattern (each 7.51 metres high). There is a pronaos in antis, an elongated naos, ending in an adyton. It is more standardized than Temple C (The columns are slightly inclined, more slender, and have entasis, the portico is supported by a distyle pronaos in antis), but it retains some archaic features, such as variation in the length of the intercolumniation and the diameter of the columns, as well as in the number of flutes per column. As with Temple C, there are many circular and square cavities in the pavement of the peristyle and of the naos, whose function is unknown. Temple D was dedicated to Athena according to epigraphic evidence[37] or perhaps to Aphrodite.[40] The large external altar is not oriented to the temple's axis, but placed obliquely near the southwest corner, which suggested that an earlier temple occupied the same site on a different axis.

East of Temple D is a small altar in front of the basement of an archaic shrine: Temple Y, also known as the Temple of the Small Metopes. The recovered metopes have a height of 84 centimetres and can be dated to 570 BC. They depict a crouching Sphinx in profile, the Delphic triad (Leto, Apollo, Artemis) in rigid frontal view, and the Rape of Europa. Another two metopes can be dated to around 560 BC and were recycled in the construction of Hermocrates’ wall. They show the quadriga of Demeter and Kore (or Helios and Selene? Apollo?) and an Eleusinian ceremony with three women holding ears of grain (Demeter, Kore, and Hecate? The Moirai?). They are kept at the Antonino Salinas Regional Archeological Museum.

Between Temples C and D are the ruins of a Byzantine village of the fifth century AD, built with recycled stone. The fact that some of the houses were crushed by the collapse of the columns of Temple C shows that the earthquake which caused the collapse of the Selinuntine temples occurred in the Medieval period.

To the north, the acropolis holds two quarters of the city (one west and the other east of the main north-south street), rebuilt by Hermocrates after 409 BC. The houses are modest, built with recycled material. Some of them contain incised crosses, a sign that they were later adapted as Christian buildings or inhabited by Christians.

Further north, before the main area of habitation, there are the grandiose fortifications for the defense of the acropolis. They are paralleled by a long gallery (originally covered) with numerous vaulted passages, followed by a deep defensive ditch crossed by a bridge, with three semicircular towers at west, north, and east. Around the outside of the north tower (which had a weapons’ store at its base) are the entrances to the east-west trench, with passages in both the walls. Only a small part of the fortifications belong to the old city – they are mostly from Hermocrates’ reconstruction and successive repairs in the fourth and third centuries. The fact that architectural elements were recycled into it demonstrates that some of the temples were already abandoned in 409 BC.

Manuzza Hill

[edit]The main residential part of the city is on the Manuzza Hill, the modern road traces the border of an area in the form of a massive trapezoid. The whole area was designed on a Hippodamian plan (reconstructed by means of aerial photography), on a slightly different orientation from the acropolis, with elongated insulae of 190 x 32 metres oriented north-south, which were originally surrounded by a defensive wall. There have not been systematic excavations in the area, but there have been some sondages, which have confirmed that the area was inhabited from the foundation of Selinus (seventh century BC) and therefore was not a later expansion of the city.

After the destruction of Selinus in 409, this area of the city was not reinhabited. The refugees returned by Hermocrates were settled only on the acropolis, which was more defensible. In 1985 a tufa structure was discovered on the hill, probably a public building of the fifth century BC.[33] Further north, beyond the housing, are two necropoleis: Manuzza and the older (seventh and sixth century) one in Galera-Bagliazzo.

Agora

[edit]Starting in 2020, the outline of the largest agora of the ancient world with an area of 33000 m2, more than twice that of Rome’s Piazza del Popolo, was unearthed.[41] The Agora, dating from the 6th century BC, was at the centre of the city, surrounded by public buildings and residential quarters. Previous excavations had revealed only one archaeological feature on the agora: an empty tomb in the middle, perhaps that of the founder.

The East Hill

[edit]

There are three temples on the East Hill, which although all in the same area on the same north-south axis seem not to have belonged to a single sacred compound (Temenos), since there is a wall separating Temple E from Temple F. This sacred complex has strong parallels with the western slopes of the acropolis of Megara, Selinus’ mothercity, which are useful (perhaps indispensable) for the correct attribution of the cults of the three temples.

Temple E the most recent of the three, dates to 460-450 BC and has a very similar plan to that of Temples A and O on the acropolis. Its current appearance is the result of anastylosis (reconstruction using the original material) carried out – controversially – between 1956 and 1959. The peristyle is 25.33 x 67.82 metres with a 6 x 15 column pattern (each 10.19 metres high) with numerous traces of the stucco which originally covered it remaining. It is a temple characterised by multiple staircases creating a system of successive levels: ten steps lead to the entrance on the eastern side, after the pronaos in antis another six steps lead into the naos and finally another six steps lead into the adyton at the rear of the naos. Behind the adyton, separated from it by a wall, was the opisthodomos in antis. A Doric frieze at the top of the walls of the naos consisted of metopes depicting people, with the heads and naked parts of the women made of Parian marble and the rest from local stone.

Four metopes are preserved: Heracles killing the Amazon Antiope, the marriage of Hera and Zeus, Actaeon being torn apart by Artemis’ hunting dogs, Athena killing the giant Enceladus, and another more fragmentary one perhaps depicting Apollo and Daphne. All of them are kept in the Museo Archeologico di Palermo. Recent sondages performed inside the temple and under Temple E have revealed that it was preceded by two other sacred buildings, one of which was destroyed in 510 BC. Temple E was dedicated to Hera as shown by the inscription on a votive stela[42][43] but some scholars deduce that it must have been dedicated to Aphrodite on the basis of structural parallels.[35]

Temple F, the oldest and smallest of the three, was built between 550 and 540 BC on the model of Temple C. Of the temples it has been the most severely spoliated. Its peristyle was 24.43 x 61.83 metres on a 6 x 14 column pattern (each 9.11 metres high), with stone screens (4.7 metres high) in the space between the columns, with false doors painted in with pilasters and architraves – the actual entrance was at the east end. It is not clear what the purpose of these screens, which are unique among Greek temples, was. Some think they were intended to protect votive gifts or to prevent particular rites (Dionysian Mysteries?) being seen by the uninitiated. Inside, there is a portico containing a second row of columns, a pronaos, a naos, and an adyton in single long, narrow structure (an archaic characteristic).

On the east side, two late archaic metopes (dated to 500 BC) were found in excavations in 1823, which depict Athena and Dionysus in the process of killing two giants. Today they are kept in the Regional Archeological Museum Antonio Salinas. Scholars have suggested that Temple F was dedicated to either Athena[34][44] or Dionysus.[35]

Temple G was the largest in Selinus (113.34 metres long, 54.05 metres wide and about 30 metres high) and was among the largest in the Greek world.[45] This building, although under construction from 530 to 409 BC (the long period of construction is demonstrated by the variation of style: the east side is archaic, while the west side is classical), remained incomplete, as shown by the absence of fluting on some of the columns and by the existence of column drums of the same dimensions ten kilometres away at Cave di Cusa, still in the process of extraction (see below).

In the massive pile of ruins it is possible to make out a peristyle of 8 x 17 columns (16.27 metres high and 3.41 metres in diameter), only one of which remains standing since it was re-erected in 1832, known in Sicilian as “lu fusu di la vecchia” (the old woman's spindle). The interior consisted of a prostyle pronaos with four columns, with two deep antae walls ending in pilasters and three doors leading to the large naos. The naos was very large and divided into three aisles – the middle one was probably open to the air (hypaethros). There were two rows of ten slender columns which supported a second row of columns (the gallery) and two lateral staircases which led to the roofspace. At the back of the central aisle was an adyton, separated from the walls of the naos and entirely contained within it. Inside the adyton, the torso of a wounded or dying giant was found as well as the very important inscription known as the “Great Table of Selinus” (see below). At the rear there was an opisthodomos in antis, which could not be accessed from the naos. Of particular interest among the ruins are some finished columns showing traces of coloured stucco and blocks of the entablature which have horseshoe-shaped grooves on the sides. Ropes were run through these grooves and used to lift them into place. Temple G probably functioned as the treasury of the city and epigraphic evidence suggests that it was dedicated to Apollo, though recent studies have suggested that it be attributed to Zeus.

At the foot of the hill by the mouth of the River Cottone was the East Port, which was more than 600 metres wide on the inside and was probably equipped with a mole or breakwater to protect the acropolis. It underwent changes in the fourth and third centuries: it was enlarged and flanked by piers (oriented north-south) and by storage areas. Of the two ports of Selinus, which are both now silted up, the West Port on the River Selinus-Modione was the main one.

The extramural quarters, dedicated to trade, commerce and port activities was arranged on massive terraces on the hillslopes

North of the modern village of Marinella, is the Buffa necropolis

Gaggera Hill with the sanctuary of the Malophoros

[edit]A path runs from the acropolis, over the river Modione to the west hill.

On Gaggera Hill there are the remains of the very ancient Selinuntine sanctuary to the goddess of fertility, Demeter Malophoros, excavated continuously between 1874 and 1915. The complex, in varying states of preservation, was built in the sixth century BC on the slope of the hill and probably served as a station for funerary processions, before they proceeded to the Manicalunga necropolis.

Initially, the place was definitely free of buildings and provided an open area for cult practices at the altar. Later, with the erection of the temple and of the high enclosure wall (temenos) it was transformed into a sanctuary. This sanctuary consisted of a rectangular enclosure (60 x 50 metres), which was entered on the east side through a rectangular propylaea in antis (built in the fifth century BC) fronted by a short staircase and a circular structure. Outside of the enclosure, the propylaea is flanked by the remains of a long portico (stoa) with seats for the pilgrims, who left evidence of themselves in the form of various altars and votives. Inside the enclosure, there was the large altar (16.3 metres long x 3.15 metres wide) in the centre, on top of a pile of ashes from the bones and other parts of the sacrifices. It had an extension to the southwest, while the remains of an earlier archaic altar are visible near the northwest extremity and there is a square pit on the temple side of the altar. Between the altar and the temple there is a canal carved in the rock which, comes from the north, through the whole area, carrying water to the sanctuary from a nearby spring. Just past the canal is the Temple of Demeter itself in the form of a megaron (20.4 x 9.52 metres), lacking a crepidoma or columns, but equipped with a pronaos, naos and adyton with a niche in the back. A rectangular service room is attached to the north side of the pronaos. The megaron had an earlier phase recognisable only at the foundation level. South of the temple there is a square structure and a rectangular structure of unclear function. North of the temple, another structure from a later period with two rooms opening onto the inside and outside of the temenos forms a secondary entrance to the enclosure. The south wall of the enclosure was periodically reinforced to fight the subsidence of the hillside. South of the propylaea, attached to the wall of the enclosure, was another enclosure dedicated to Hecate. This took the form of a square, with the shrine in the east corner, near an entrance, while in the south corner there was a small square paved space of uncertain purpose.

Fifteen metres north there was another square enclosure (17 x 17 metres) dedicated to Zeus Meilichios (Honey-sweet Zeus) and Pasikrateia (Persephone), much of which remains, but it is not easy to understand the various structures, which were built at the end of the fourth century BC. It consists of an enclosure wall surrounded by various types of column on two sides (part of a Hellenistic portico), a small prostyle temple in antis (5.22 x 3.02 m) at the back of the enclosure with monolithic Doric columns, but an ionic entablature, and two others in the centre of the enclosure. Outside, to the west, the pious dedicated many small steles topped by images of the divine pair (two faces, one male and one female) made with shallow incisions. Along with them were found ashes and remains of offerings, evidence of convergence between the Greek cult of the Chthonic gods and Punic religion. A very large number of finds came from the Sanctuary of the Malophoros (all kept at the Museum in Palermo): carved reliefs of mythological scenes, around 12,000 votive figurines in terracotta from the seventh to fifth centuries BC; large bust-shaped censers depicting Demeter and perhaps Tanit, a great quantity of Corinthian pottery (late proto-Corinthian and early Corinthian), a bass-relief depicting the Rape of Persephone by Hades found at the entrance to the enclosure. Christian remains, especially lamps with the monogram XP, prove the presence of a Christian religious community in the area of the sanctuary between the third and fifth centuries AD.

A little further up the slopes of Gaggera Hill is the spring from which the Sanctuary of the Malophoros gets its water. Fifty metres downstream of it is a building once believed to be a temple (the so-called “Temple M”), which is actually a monumental fountain. It is rectangular in shape (26.8 metres long x 10.85 metres wide x 8 metres high), constructed of squared blocks and contained a cistern, a closed basin protected by a portico with columns and an access staircase of four steps with a large paved area in front of it. The building is in the doric style and is dated to the middle of the sixth century mainly by the architectural terracotta discovered there. The fragments of metopes with the Amazonomachy, although found nearby, do not belong to the building, which had small, smooth metopes. Another megaron, a few hundred metres to the northeast of the Sanctuary of the Malophoros, has been excavated recently.

The Necropoleis

[edit]

Around Selinus some areas used as necropoleis can be identified.

- Buffa (end of the seventh century BC and the sixth century): north of the East Hill. The site contains a triangular votive ditch (25 x 18 x 32 metres) with terracotta, vases and animal remains (probably from sacrifices).[33]

- Galera Bagliazzo (sixth century BC): northeast of Mannuzza Hill. In the tombs dug into the tufa here, none apparently singular, are grave goods of various styles. In 1882 the statues called the Ephebe of Selinus was brought to light here; today it is in the Civic museum of Castelvetrano.[33]

- Pipio Bresciana and Manicalunga Timpone Nero (Sixth to Fifth century BC): west of Gaggera Hill, the most extensive of Selinus’ necropoleis. Given its distance from the city centre it is not clear whether it was the necropolis of the city or of a suburban area. As well as evidence of inhumations, there are amphorae and pithoi which testify to the practice of cremation. The sarcophagi are in terracotta or tufa. There are also covered rooms.[33]

Cave di Cusa

[edit]

Cave di Cusa (The Quarries of Cusa) are made up of banks of limestone near Campobello di Mazara, thirteen kilometres from Selinus. They were the stone quarries from which the material for the buildings of Selinus came. The most notable element of the quarries is the sudden interruption of operations caused by the attack on the city in 409 BC. The sudden departure of the quarrymen, stonemasons and other workers means that today it is possible not just to reconstruct, but to see all the various stages of the quarrying process from the first deep circular cuts to the finished drums waiting to be transported. Along with the column drums, there are also some capitals and also square incisions for quarrying square blocks, all intended for the temples of Selinus. Of the drums that had already been extracted, some were found ready for transport and others, already on the way to Selinus were abandoned on the road. Some gigantic columns, definitely intended for Temple G, are found in the area west of Cave di Cusa, also in the state in which they were originally abandoned.

Coinage

[edit]The coins of Selinus are numerous and various. The earliest, as already mentioned, bear merely the figure of a parsley-leaf on the obverse. Those of somewhat later date represent a figure sacrificing on an altar, which is consecrated to Aesculapius, as indicated by a cock that stands below it. The subject of this type evidently refers to a story related by Diogenes Laërtius[46] that the Selinuntines were afflicted with a pestilence from the marshy character of the lands adjoining the neighboring river, but that this was cured by works of drainage, suggested by Empedocles. A figure standing on some coins is the river-god Selinus, who was thus made conducive to the salubrity of the city.

The Seal of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine is based on a coin of Selinus struck in 466 BC which was designed by the sculptor and medallist Allan Gairdner Wyon FRBS RMS (1882-1962). It shows two Greek gods associated with health - Apollo, the god of prophecy, music and medicine, and his sister Artemis, goddess of hunting and chastity, and comforter of women in childbirth - in a horse-drawn chariot. Artemis is driving while her brother the great archer is shooting arrows. The fruitful date palm was added to indicate the tropical activities of the School but also has a close connection with Apollo and Artemis: when their mother Leto gave birth to them on the island of Delos, miraculously a palm sprang up to give her shade in childbirth. Asclepius, Apollo's son, was the god of ancient Greek medicine, and was frequently shown holding a staff entwined with a snake. Snakes were used in this healing cult to lick the affected part of the patient. Significantly Asclepius' daughters were Hygeia (the goddess of health) and Panacea (the healer of all ailments). Asclepius' staff with a snake coiled round it (known as a symbol of the medical professions) was placed at the base of the seal to emphasise the medical interests of the School. The Seal was redesigned in 1990 by Russell Sewell Design Associates, and is retained today within the current School logo.[47]

-

Didrachm bearing selinon leaf, two pellets above. Incuse square divided into eight sections. c. 540/530-510 BC.

-

Didrachm, c. 480-466 BC.

-

Didrachm, c. 466-415 BC.

-

Didrachm, c. 466-415 BC.

-

Selinos AR Tetradrachm 82000284

Art and other discoveries from Selinus

[edit]- The Great Table of Selinus was discovered in the adyton of Temple G in 1871. It contains a catalogue of the cults practiced at Selinus and is therefore the basis for all attempts to determine the cults of the various temples of Selinus. It says "The Selinuntines are victorious thanks to the gods Zeus, Phobos, Heracles, Apollo, Poseidon, the Tyndaridae, Athena, Demeter, Pasicrateia and other gods, but especially thanks to |eus. After the restoration of peace it was decreed that a work be done in gold with the names of the gods inscribed, with Zeus at the top and that it be deposited in the Temple of Apollo, and that sixtent talents of gold be spent on this."

- The figurative art recovered at Selinus is very important and much of it is kept in the Regional Archeological Museum Antonio Salinas. The best examples of the distinctive archaic artistic style of Selinus are the metopes (most of which are discussed above in the context of their temples).

- The Ephebe of Selinus is a bronze statue of an ephebe offering a libation, cast in a severe style, with features typical of the Greek West and dating to 470 BC. Apart from the Ram of Syracuse, it represents the only large-scale bronze work which has survived from Greek Sicily. It is kept at Castelvetrano. The discovery happened by chance in the Ponte Galera district near Selinunte, home to one of the Selinuntine necropolises. It was discovered by chance in 1882 by two young boys digging the earth hoping to find gold objects to sell from the rich tombs of Selinunte. It was likely laid in a clay sarcophagus and hidden during dangerous times as it was not part of a funerary collection. At the end of the Punic invasion the owners had never recovered it so it had escaped the clutches of the Carthaginians.

- The necropoleis have yielded a very large number of Proto-Corinthian, Corinthian, Rhodian and Attic black figure vases, but no unique local pottery since Selinus did not produce fine pottery.

- Some of the most valuable votive material was found in the Sanctuary of the Malophoros, such as terracotta statuettes, ceramics, incense-busts, altars, a bass-relief depicting the Rape of Persephone by Hades, and Christian lamps have been discussed above. These items are kept in the Museo Archeologico di Palermo and some of them are on display.

Metopes of Selinus (gallery)

[edit]-

Temple C

Quadriga of Apollo -

Temple C

Perseus kills Medusa -

Temple C

Heracles and the Cercopes -

Temple E

Artemis and Actaeon -

Temple E

Athena and Enceladus -

Temple E

Zeus and Hera -

Temple E

Heracles and Antiope -

Temple F

Gigantomachy -

Temple F

Gigantomachy -

Temple Y

Europa on the bull -

Temple Y

Dancing scene -

Temple Y

Demeter and Kore in a quadriga -

Temple Y

The Delphic triad

Terracotta statuettes (gallery)

[edit]-

Korai (maidens) with doves

-

Korai

-

Kneeling kouros

-

Tanagrine-style offering

-

Heads of votives

-

Head of a votive

-

Female mask

-

Sphinx

-

Siren

-

Bulls at rest

General gallery

[edit]-

The acropolis as seen from the east

-

Temple E

-

Temple E front

-

Temple E back

-

Temple C

-

Aerial photo of Temple C

-

Sanctuary of Demeter Malophoros

See also

[edit]- List of ancient Greek cities

- Marinella di Selinunte

- Architecture of Ancient Greece

- Cave di Cusa

- Greek temple

- List of Greco-Roman roofs

Notes

[edit]- ^ Morris, A.E.J. (2013). History of Urban Form Before the Industrial Revolution. Taylor & Francis. p. 53. ISBN 9781317885146. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- ^ Thucydides vi. 4, vii. 57; Scymnus 292; Strabo vi. p. 272.

- ^ Thucydides vi. 4; Diodorus Siculus xiii. 59; Hieronymus Chron. ad ann. 1362; Clinton, Fast. Hell. vol. i. p. 208.

- ^ σέλινον, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Diodorus Siculus v. 9.

- ^ xi. 86. Lilybaeum was only founded in 396 BC

- ^ Diodorus Siculus xiii. 54.

- ^ Herodotus v. 46.

- ^ Herodotus v. 46.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus xi. 21, xiii. 55.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus xi. 68

- ^ Thucydides vi. 20.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus xiii. 55.

- ^ Danner, Peter (1997). "Megara, Megara Hyblaea and Selinus: the Relationship between the Town Planning of a Mother City, a Colony and a Sub-Colony in the Archaic Period". Urbanization in the Mediterranean in the Ninth to Sixth Centuries B.C. Acata Hyperborea. Vol. 7. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. p. 151. ISBN 9788772894126.

- ^ Zuchtriegel, Gabriel (2011). "Zur Bevolkerungszahl Selinunts Im 5. Jh. v. Chr". Historia (in German). 60 (1): 121. doi:10.25162/historia-2011-0005. S2CID 252454566.

- ^ Thucydides vi. 6; Diodorus Siculus xii. 82.

- ^ Thucydides vi. 47

- ^ Thucydides vii. 50, 58; Diodorus Siculus xiii. 12.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus xiii. 43, 44.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus xiii. 54-59.

- ^ a b Diodorus Siculus xiii. 59, 114.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus xiii. 63.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus xiv. 47

- ^ Diodorus Siculus xv. 17

- ^ Diodorus Siculus xv. 73

- ^ Diodorus Siculus xix. 71.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus xxii. 10. Exc. H. p. 498.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus xxiii. 1, 21; Polybius i. 39.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus xxiv. 1. Exc. H. p. 506.

- ^ iii. 8. s. 14

- ^ Strabo vi. p. 272; Ptolemy iii. 4. § 5.

- ^ Antonine Itinerary p. 89; Tabula Peutingeriana

- ^ a b c d e f "www.selinunte.net". Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- ^ a b c Sabatino Moscati, Italia archeologica, Novara, De Agostini, 1973, vol. 1, pp. 120-129

- ^ a b c Filippo Coarelli; Mario Torelli, Sicilia (Guide archeologiche Laterza), Bari, Laterza, 1988, pp. 72-103

- ^ The name “Temple of Empedocles” was given to it in 1824 by the excavator, Hittorf, because he thought it had been dedicated to him for his good deed of draining the watery marshes of the Selinuntine rivers and thereby ending the frequent malaria epidemics

- ^ a b IG XIV 269

- ^ Margaret Guido; Vincenzo Tusa, Guida archeologica della Sicilia, Palermo, Sellerio, 1978, pp. 68-80

- ^ "Temple Decoration and Cultural Identity in the Archaic Greek World: The Metopes of Selinus". New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007. 370 pp. June 30, 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ Touring Club Italiano, Guida d'Italia – Sicilia, Milano, 1989, pp. 324-330

- ^ The excavations in Selinunte, Italy, which has the largest Agora in the Ancient World, “The results have gone well beyond expectations” https://arkeonews.net/the-excavations-in-selinunte-italy-which-has-the-largest-agora-in-the-ancient-world-the-results-have-gone-well-beyond-expectations/

- ^ IG XIV 271

- ^ Tony Spawforth, The Complete Greek Temples 2006, p. 131.

- ^ Amedeo Maiuri, Arte e civiltà nell'Italia antica, (Conosci l'Italia, vol. IV), Milano, 1960, pp. 79-80, 89-92, 106-108

- ^ Along with the Olympeion at Acragas and surpassed only by the Temple of Apollo near Miletus and the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus

- ^ viii. 2. § 11

- ^ "The School Seal | London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine | LSHTM". www.lshtm.ac.uk. Retrieved 2015-09-25.

References

[edit]- Beckmann, Martin (2002). "The 'Columnae Coc(h)lides' of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius". Phoenix. 56 (3/4): 348–357. doi:10.2307/1192605. JSTOR 1192605.

- Hesberg, Henner von (2023). Die Tötung der Typhon - figürlich geschmückte Tonaltäre des 6. Jh. v. Chr. aus Selinunt. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447119948.

- Ruggeri, Stefania (2006). Selinunt. Messina: Edizioni Affinità Elettive. ISBN 88-8405-079-0.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray. ((cite encyclopedia)): Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links

[edit]- Official website (in Italian)

- The excavations at Selinunte by New York University

- Animated virtual reconstruction of Selinunte Temple C

- Archaeological Park of Selinunte

- Selinunte—photo gallery

| Algeria |

|

|---|---|

| Cyprus | |

| Greece | |

| Israel | |

| Italy | |

| Lebanon | |

| Libya | |

| Malta |

|

| Morocco | |

| Portugal |

|

| Spain | |

| Syria | |

| Tunisia | |

| Other | |

Archaeological sites in Sicily | ||

|---|---|---|

| Province of Agrigento | ||

| Province of Caltanissetta | ||

| Province of Catania | ||

| Province of Enna | ||

| Province of Messina | ||

| Province of Palermo | ||

| Province of Ragusa | ||

| Province of Syracuse | ||

| Province of Trapani | ||

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Geographic | |