Canadarm2 installs the PMM Leonardo | |

| Names | Space Transportation System-133 |

|---|---|

| Mission type | ISS assembly |

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 2011-008A |

| SATCAT no. | 37371 |

| Mission duration | 12 days, 19 hours, 4 minutes, 50 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 8,536,190 kilometres (5,304,140 mi) |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Discovery |

| Launch mass | Orbiter: 121,840 kilograms (268,620 lb) Stack: 2,052,610 kilograms (4,525,220 lb) |

| Dry mass | 92,867 kilograms (204,736 lb)[1] |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 6 |

| Members | |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | February 24, 2011, 21:53:24 UTC[2][3][4] |

| Launch site | Kennedy Space Center, LC-39A |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | March 9, 2011, 16:58:14 UTC |

| Landing site | Kennedy SLF Runway 15 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee altitude | 208 kilometres (129 mi)[5] |

| Apogee altitude | 232 kilometres (144 mi)[5] |

| Inclination | 51.6°[5] |

| Period | 88.89 minutes[5] |

| Epoch | February 25, 2011[5] |

| Docking with ISS | |

| Docking port | PMA-2 (Harmony forward) |

| Docking date | February 26, 2011, 19:14 UTC |

| Undocking date | March 7, 2011, 12:00 UTC |

| Time docked | 8 days, 16 hours, 46 minutes |

From left to right: Alvin Drew, Nicole Stott, Eric Boe, Steven Lindsey, Michael Barratt and Steve Bowen | |

STS-133 (ISS assembly flight ULF5)[6] was the 133rd mission in NASA's Space Shuttle program; during the mission, Space Shuttle Discovery docked with the International Space Station. It was Discovery's 39th and final mission. The mission launched on February 24, 2011, and landed on March 9, 2011. The crew consisted of six American astronauts, all of whom had been on prior spaceflights, headed by Commander Steven Lindsey. The crew joined the long-duration six person crew of Expedition 26, who were already aboard the space station.[7] About a month before lift-off, one of the original crew members, Tim Kopra, was injured in a bicycle accident. He was replaced by Stephen Bowen.

The mission transported several items to the space station, including the Permanent Multipurpose Module Leonardo, which was left permanently docked to one of the station's ports. The shuttle also carried the third of four ExPRESS Logistics Carriers to the ISS, as well as a humanoid robot called Robonaut.[8] The mission marked both the 133rd flight of the Space Shuttle program and the 39th and final flight of Discovery, with the orbiter completing a cumulative total of a whole year (365 days) in space.

The mission was affected by a series of delays due to technical problems with the external tank and, to a lesser extent, the payload. The launch, initially scheduled for September 2010, was pushed back to October, then to November, then finally to February 2011.

Mission payload

[edit]Permanent Multipurpose Module

[edit]

STS-133 left Leonardo (named after the famed Italian Renaissance inventor Leonardo da Vinci), one of the three Multi-Purpose Logistics Modules (MPLMs), on the space station as a Permanent Multipurpose Module (PMM).[9][10] PMM Leonardo added much-needed storage space on the ISS, and was launched with a near-full load of payloads.

The construction of the Leonardo MPLM by the Italian Space Agency commenced in April 1996. In August 1998, after the completion of primary construction, Leonardo was delivered to the Kennedy Space Center (KSC). In March 2001, Leonardo made its first mission on Discovery as part of the STS-102 flight. The liftoff of Leonardo inside Discovery's payload bay on STS-102 marked the first of seven MPLM flights prior to STS-133.

With the landing of Discovery after the STS-131 mission, Leonardo was transferred back to the Space Station Processing Facility at Kennedy Space Center. Leonardo began receiving modifications and reconfigurations immediately to convert it for permanent attachment to the space station and to facilitate on-orbit maintenance.[11] Some equipment was removed to reduce the overall weight of Leonardo. These removals resulted in a net weight loss of 178.1 lb (80.8 kg). Additional modifications to Leonardo included the installation of upgraded multi-layer insulation (MLI) and Micro Meteoroid Orbital Debris (MMOD) shielding to increase the ability of the PMM to handle potential impacts of micrometeoroids or orbital debris; a Planar Reflector was installed at the request of the Japanese Space Agency (JAXA).

Following berthing to the space station, the contents of Leonardo were emptied and moved to appropriate locations on the ISS. Once JAXA's Kounotori 2 (HTV-2) arrived in February 2011, Leonardo's now-unnecessary launch hardware was transferred to HTV2 for ultimate destruction in Earth's atmosphere.

Activities to reconfigure Leonardo following STS-133 spanned multiple station crew increments.

ExPRESS Logistics Carrier 4

[edit]

The Express Logistics Carrier (ELC) is a steel platform designed to support external payloads mounted to the space station starboard and port trusses with either deep space or Earthward views. On STS-133, Discovery carried the ELC-4 to the station to be positioned on the starboard 3 (S3) truss' lower inboard passive attachment system (PAS). The total weight of the ELC-4 is approximately 8,235 pounds.

The Express Logistics Carrier 4 (ELC-4) carried several Orbital Replacement Units (ORUs). Among these were a Heat Rejection System Radiator (HRSR) Flight Support Equipment (FSE), which takes up one whole side of the ELC. The other primary ORUs were the ExPRESS Pallet Controller Avionics 4 (ExPCA #4). The HRSR launching on ELC4 was a spare, if needed, for one of the six radiators that are part of the station's external active thermal control system.

Robonaut2

[edit]

Discovery carried the humanoid robot Robonaut2 (also known as R2) to the International Space Station (ISS). The microgravity conditions aboard the space station provide an ideal opportunity for robots like R2 to work with astronauts. Although the robot's primary initial task is teaching engineers how dexterous robots behave in space, it may eventually, through upgrades and advancements, assist spacewalking astronauts to perform scientific work once it has been verified as functional on the space station.[12] It was the first humanoid robot in space, and was stowed on board the Leonardo PMM. Once Robonaut2 was unpacked, it began initial operation inside the Destiny module for operational testing, but over time, both its location and its applications could expand.

Robonaut2 was initially designed as a prototype to be used on Earth. For its journey to the ISS, R2 received a few upgrades. Outer skin materials were exchanged to meet the ISS's strict flammability requirements. Shielding was added to reduce electromagnetic interference and onboard processors were upgraded to increase R2's radiation tolerance. The original fans were replaced with quieter ones to accommodate the station's restrictive noise environment, and the power system was rewired to run on the station's direct current system. Tests were conducted to make sure the robot could both endure the harsh conditions in space and exist in it without doing damage. R2 also underwent vibration testing that simulated the conditions it would experience during its launch onboard Discovery.

The robot weighs 300 pounds (140 kg) and is made out of nickel-plated carbon fiber and aluminum. The height of R2 from waist to head is 3 feet 3.7 inches (100.8 cm), and it has a shoulder width of 2 feet 7.4 inches (79.8 cm). R2 is equipped with 54 servo motors and has 42 degrees of freedom.[13] Powered by 38 PowerPC processors, R2's systems run at 120 volts DC.

SpaceX DragonEye sensor

[edit]

Space Shuttle Discovery also carried the Developmental Test Objective (DTO) 701B payload using Advanced Scientific Concepts, Inc.'s DragonEye 3D Flash LiDAR detection and ranging (LIDAR) sensor. The addition of the pulsed laser navigation sensor was the third time a Space Shuttle provided assistance to the commercial space company SpaceX, following STS-127 and STS-129. The DragonEye on STS-133 incorporated several design and software improvements from the version flown on STS-127 to provide increased performance. Its inclusion on STS-133 was part of a final test run ahead of being fully implemented on SpaceX's Dragon spacecraft, which had its maiden flight in December 2010.[14]

The navigation sensor provides a three-dimensional image based on the time of flight of a single laser pulse from the sensor to the target and back. It provides both range and bearing information from targets that can reflect the light back such as the pressurized mating adapter 2 (PMA2) and those on the station's Japanese Kibo laboratory.

The DragonEye DTO was mounted onto Discovery's existing trajectory control system carrier assembly on the orbiter's docking system. SpaceX took data in parallel with Discovery's Trajectory Control Sensor (TCS) system. Both the TCS and DragonEye "looked" at the retroreflectors that are on the station. After the mission, SpaceX compared the data DragonEye collected against the data collected by the TCS to evaluate DragonEye's performance.

The sensor was installed onto Discovery two weeks later than planned, following a laser rod failure during testing.[15]

Other items

[edit]STS-133 carried the signatures of more than 500,000 students who participated in the 2010 Student Signatures in Space program, which was jointly sponsored by NASA and Lockheed Martin. The students added their signatures to posters in May 2010 as part of the annual Space Day celebration. Through their participation, students also received standards-based lessons that contained a space theme.[citation needed] Student Signatures in Space has been active since 1997. In that time, nearly seven million student signatures from 6,552 schools were flown on ten Space Shuttle missions.[16]

Also carried aboard Discovery were hundreds of flags, bookmarks and patches which were distributed when the shuttle returned to Earth. The mission also flew two small Lego Space Shuttles, in honor of an educational partnership between Lego and NASA. Astronauts also carried personal mementos including medallions with connections to their schools or military careers, as well as a William Shakespeare "action figure" from the English Department of the University of Texas, a stuffed giraffe mascot from the Hermann Children's Hospital at the University of Texas, T-shirts from Lomax Junior High School in La Porte, Texas, a blue Hawaiian shirt from NASA Johnson Space Center's Education Office, and a shirt from a volunteer fire department.[17]

Crew

[edit]| Position | Astronaut[18][19] | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Steven Lindsey Fifth and last spaceflight | |

| Pilot | Eric Boe Second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | Nicole Stott Second and last spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | Alvin Drew Second and last spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | Michael Barratt Second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 4 | Stephen Bowen Third spaceflight | |

NASA announced the STS-133 crew on September 18, 2009, and training began in October 2009. The original crew consisted of commander Steven Lindsey, pilot Eric Boe, and mission specialists Alvin Drew, Timothy Kopra, Michael Barratt, and Nicole Stott. However, on January 19, 2011, about a month before launch, it was announced that Stephen Bowen would replace original crew member Tim Kopra, after Kopra was injured in a bicycle accident.[20] All six crew members had flown at least one spaceflight before; five of the crew members, all but commander Steven Lindsey, were part of NASA's Astronaut Group 18, all being selected in the year 2000.[21]

The mission commander, Steven Lindsey, handed over his position as Chief of the Astronaut Office position to Peggy Whitson in order to lead the mission.[22] For the first time, two mission crew members were in space when a crew assignment announcement was made, as Nicole Stott and Michael Barratt were aboard the ISS as part of the Expedition 20 crew.[22] During STS-133, Alvin Drew became the last African-American astronaut to fly on the Space Shuttle, as no African-Americans were among the crews of STS-134 and STS-135. Having flown onboard Atlantis' STS-132 mission, Bowen became the first and the only NASA astronaut to be launched on two consecutive missions, until Doug Hurley launched aboard Crew Dragon Demo-2 in May 2020, after having previously launched on STS-135.

-

The crew poses for a photo at the KSC (including Bowen).

-

Mission poster (with Kopra instead of Bowen).

-

Lindsey, far left, presents a montage to Barack Obama as crew members Barratt, Boe, Stott and Bowen look on.

Crew training

[edit]Terminal countdown demonstration test

[edit]On October 12, 2010, the STS-133 crew arrived at the Kennedy Space Center to conduct the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test (TCDT). The TCDT consisted of training for both the crew and the launch team that simulated the final hours up until launch. During the TCDT, the crew went through a number of exercises that included rescue training and a launch day simulation that included everything that would happen on launch day – except the launch. Commander Steve Lindsey and Pilot Eric Boe also performed abort landings and other flight aspects in the Shuttle Training Aircraft (STA). For the TCDT, the crew also received a briefing from NASA engineers, outlining the work that had been carried out on Discovery during the STS-133 processing flow. After successfully completing all the TCDT tasks, the crew returned to the Johnson Space Center on October 15, 2010.[23]

Flying aboard NASA T-38 training jets, the six astronauts returned to Kennedy Space Center on October 28, 2010, for final pre-launch preparations.[24]

-

The crew gathered for the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test.

-

The Launch Pad 39A during the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test.

On January 15, 2011, Timothy Kopra, scheduled as the lead spacewalker for the mission at the time, was injured in a bicycle accident near his Houston-area home, reportedly breaking his hip.[25] He was replaced by Stephen Bowen on January 19, 2011. The replacement did not affect the targeted launch date.[20] This is to date the closest to a scheduled launch that a Space Shuttle crewmember has been replaced. During the Apollo program, Jack Swigert replaced Ken Mattingly three days prior to the launch of Apollo 13.[25]

Shuttle processing

[edit]STS-133 was originally manifested for launch on September 16, 2010. In June 2010, the launch date was moved to the end of October 2010 and the mission was set to take place before STS-134, which in turn had been rescheduled to February 2011. STS-133 had the longest vertical flow period (170 days) since STS-35 (185 days).

Discovery was moved from its hangar in the Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF)-3 to the nearby 52-story Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) on September 9, 2010. The shuttle emerged from OPF-3 at 06:54 EDT and the rollover was done at 10:46 EDT when Discovery came to a rest in the VAB's transfer aisle.[26] The quarter-mile trip between the OPF-3 and VAB was the 41st rollover for Discovery. The rollover was originally planned at 06:30 EDT on September 8, 2010. The move did not commence due to the unavailability of fire suppression systems because of a broken water main near the VAB and turn basin that runs out to the shuttle launch pads.[27][28]

The two SRBs were designated as flight set 122 by contractor Alliant Techsystems and were made up from one new segment and remaining segments reused across 54 earlier shuttle missions dating back to STS-1.[29] Inside the VAB, engineers attached a large sling to Discovery and the orbiter was rotated vertically. The orbiter was lifted into the high bay where its external tank (ET-137) and boosters were waiting to be mated. During the mating operations, an internal nut pre-positioned inside the aft compartment of the orbiter slipped out of position and fell away inside the compartment.[30] Engineers initially were worried that the orbiter would have to be removed from the ET and placed back in a horizontal orientation to make repairs. However, later they successfully accessed the area inside the aft compartment, and re-positioned the nut to complete the repairs. The bolting of the orbiter to its ET ('hard mate') was completed early on the morning of September 11, 2010, at 09:27 EDT.

The shuttle's 44th rollout to the launch pad was scheduled to begin at 20:00 EDT on September 20, 2010.[31] NASA sent out more than 700 invitations to shuttle workers so they could bring their families to watch Discovery's journey to the pad. However, the shuttle began the 3.4-mile trek from the VAB to the pad earlier than planned at about at 19:23 EDT on September 20, 2010.[32] Discovery took about six hours to arrive at Pad 39A. The shuttle was secured on the launch pad by 01:49 EDT the next day.

-

Discovery being lowered onto its external fuel tank and solid rocket boosters in High Bay 3 of the Vehicle Assembly Building.

-

The Space Shuttle Discovery attached to Launch Pad 39A on 21 September 2010.

-

Discovery at Launch Pad 39A on 1 February 2011.

-

Discovery is seen shortly after the Rotating Service Structure was rolled back on 23 February 2011.

Orbital Maneuvering System vapor leak

[edit]On October 14, 2010, engineers at the launch pad first discovered a small leak in a propellant line for Discovery's orbital maneuvering system (OMS) engines. The leak was detected after they noticed a fishy smell coming from the aft of the shuttle, thought of as a sign of fuel vapor in the air.[23] Upon inspection, the leak was found at a flange located at the interface where two propellant lines met in Discovery's aft compartment. The line carried monomethyl hydrazine (MMH) propellant, one of two chemicals (the other is an oxidizer, nitrogen tetroxide) used to ignite the OMS engines. Engineers replaced an Air Half Coupling (AHC) flight cap. However, the new cap failed to solve the problem since vapor checks still showed signs of a leak. An aspirator was activated to collect the vapor at the leak-site allowing work to continue in other locations around the aft segment of Discovery.

It was believed that the leak was in the crossfeed flange area – a problem with associated seals. On October 18, 2010, after an afternoon review, engineers were asked to double-check the torque on six bolts around the suspected leaky flange fitting and tighten if necessary.[33] Subsequent leak tests showed again signs of seepage, and the task of solving the issue required the draining of both the left and right OMS tanks of the shuttle and a unique in-situ repair at the pad to avoid a rollback.[34] On October 23, 2010, engineers completed the removal and replacement of the two seals on the right OMS crossfeed flange, after the education (a vacuum-related procedure, used to completely clear the plumbing of the toxic MMH) of the plumbing was completed ahead of the schedule by over a day.[35] Later, testing indicated that the new seals were properly seated and holding pressure with no signs of additional seepage.[36] Normal pad operations commenced soon after allowing managers to press forward with the confirmation of a November 1, 2010, target launch date, with fuel reloading into the OMS tanks beginning on the morning of October 24, 2010.

Main engine controller problem

[edit]On November 2, while readying Discovery for launch, engineers reported an electrical issue on the backup Main Engine Controller (MEC) mounted on Engine No. 3 (SSME-3). Earlier in the morning, engineers said that the problem had been solved, however, another glitch in the system raised concerns and additional troubleshooting was ordered. Troubleshooting followed and indicated the problem was related to "transient contamination" in a circuit breaker. NASA Test Director Steve Payne, addressing reporters, told that after troubleshooting and power cycles, the controller powered up normally. However, at the same time the problem was thought to be a non-issue, an unexpected voltage drop was observed.[37]

In a Mission Management Team (MMT) meeting held later that day, managers decided to scrub the launch for at least 24 hours to work towards flight rationale.[38]

Ground Umbilical Carrier Plate leak

[edit]

On November 5, 2010, Discovery's launch attempt, a hydrogen leak was detected at the Ground Umbilical Carrier Plate (GUCP) during the fueling process. The plate was an attachment point between the external tank and a 17-inch pipe that carried gaseous hydrogen safely away from the tank to the flare stack, where it was burned off. All had been proceeding to plan with the tank "fast filled" during tanking, until the first leak indication was revealed. Firstly, a 33,000 ppm leak then reduced to a level below 20,000 ppm was recorded. The Launch Commit Criteria limit was 40–44,000 ppm. The leak was only being observed during the cycling of the vent valve to "open" to release the gaseous hydrogen from the tank to the flare stack. Controllers decided to stop valve cycling in order to increase the pressure and attempt to force a seal before attempting to complete the fast-fill process. At this stage, the leak spiked and remained at the highest 60,000 ppm level (likely even at a higher value), indicating a serious problem with the GUCP's seal.

Shuttle launch director Mike Leinbach characterized the leak as "significant," similar to what was seen on STS-119 and STS-127, although the rate was higher in magnitude and occurred earlier in the fueling process.

After the day required to make the tank safe by purging remaining hydrogen gas with helium gas, NASA engineers prepared for the disconnection of the vent arm and the significant number of lines prior to taking their first look at the GUCP. On the night of November 9, technicians began disconnecting the GUCP by unhooking and lowering the hydrogen vent line. Teams performed an initial inspection of the flight seal and a quick disconnect prior to sending them to labs for thorough engineering analysis. Engineers reported an unevenly (asymmetrically) compressed internal seal and the quick disconnect hardware also seemed to have a less concentric fit than pre-fueling measurements indicated.[39] Inspections also confirmed the condition of the hardware did not match the observations documented when it was installed on the external tank inside the VAB.[40]

On the morning of November 12, teams began installing a new GUCP and completed the GUCP work over the next two days. The new plate was previously fit checked on the external tank at the Michoud Assembly Facility and yielded substantially better concentricity values than was obtained with the old and removed GUCP. Technicians took extra measurements to ensure the best possible alignment of the newly installed GUCP. Teams began installing the flight seal and quick disconnect on November 15.

Cracks in the external tank

[edit]

Additional inspection of the tank revealed cracks in foam insulation in the flange between the intertank and liquid oxygen tank. The cracks are believed to have occurred about an hour after super-cold propellants began flowing into the external tank for the November 5 launch attempt. The cracks in the tank were the first to be found at the launch pad.

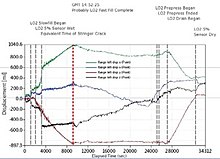

In December 2010, with the Shuttle still on the launch pad, a full tanking test was performed to understand that failure modes of the SOFI foam fracturing. The ET Tanking Test involved a full flight loading of the ET (External Tank) with liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen fuels, while monitoring the ET near the SRB Thrust Beam where the fracture(s) occurred. External Tank Photogrammetry Team used two full-field Optical Strain systems, specifically configured for the tests by NASA Glenn and Trilion Quality Systems. The Trilion Optical Strain systems (ARAMIS) measured the full-field displacements and strains of the ET from the cryogenic fuel loading during the 6-hour test (see data images). The Trilion Optical Strain cameras were fiber optically linked to the control room in the Launch Control Center 3 miles away from the launch pad, where the data was monitored during the test. Trilion Quality Systems worked with NASA Marshall over the next week to understand the data, compare with ET computer models, allowing NASA to understand the failure modes and to be able implement the repairs. The Optical Strain patterning was still on the ET during launch on February 24, 2011, travelling with it into space. The External Tank Photogrammetry Team was, later that year, awarded the Space Flight Awareness Award, and Trilion's Tim Schmidt, the Silver Snoopy Award, by astronaut Mike Foreman. [41]

The insulation was cut away for additional inspection, revealing two additional 9-inch metal cracks on either side of an underlying structural rib called "stringer S-7-2". NASA managers then decided to cut away additional foam and observed two more cracks on a stringer known as S-6-2 adjacent to the two original cracks. They were found on the far left of removed foam on the flange area between the intertank and the liquid oxygen tank. However, these cracks appeared to have suffered less stress than the others found.[42][43] No cracks were found in stringers on the right side. NASA suspected the use of a lightweight aluminum-lithium alloy in the tanks contributed to the crack problem. Repairs commenced while the shuttle remained on the pad.[44] An environmental enclosure was erected around the known damage site to facilitate the ongoing repairs and eventually to apply fresh foam insulation. On November 18, as part of the repairs, technicians installed new sections of metal, called "doublers" because they are twice as thick as the original stringer metal providing additional strength, to replace the two cracked stringers on Discovery's external tank.

Scanning of the stringers on the liquid oxygen/intertank flange was completed on November 23.[45] NASA also performed backscatter scanning of the lower liquid hydrogen/intertank flange stringers on November 29.

Program managers identified the analysis and repairs that were required to safely launch the shuttle, and this analysis was reviewed at a special Program Requirements Control Board (PRCB) held on November 24. Managers announced at that meeting that the launch window available in early December would be passed up, with a new target of December 17 set, but cautioned that the launch could slip into February 2011. After reviewing the space station's December traffic model following the realigned Johannes Kepler ATV's launch date, NASA had identified a potential launch window in mid-/late-December 2010. The December 17, 2010, date was preferred because it would have allowed the shuttle to carry more stored oxygen to the International Space Station to help it deal with oxygen generation issues, which the crew had dealt with for several months.[46] "What we've told the agency leadership is that clearly we're not ready for the 3 to 7 December window that's coming up next week," John Shannon, NASA's SSP manager, said in a news conference held after the special PCRB. "We'll leave the option open for a launch window for 17 December, but a lot of data has to come together to support that".[47]

Johannes Kepler ATV rescheduled

[edit]The launch date of February 24, 2011, was officially set after the Flight Readiness Review meeting on February 18, 2011. Reviews of previous problems, including the GUP vent line connection, external tank foam and external tank stringer cracks, were found to be positive. Additionally, flight rules which required a 72-hour separation between dockings at the International Space Station threatened to delay the launch by at least a day due to the delayed launch of the ESA's uncrewed Johannes Kepler ATV supply craft. Managers instead decided to press ahead with the countdown allowing for a possible stand down; had docking issues arisen with the ATV, STS-133 would have stood down for 48 hours.[48] The Kepler ATV docked successfully at 10:59 UTC, February 24, 2011.[49]

Launch attempts

[edit]- All times Eastern Time, first 5 are while daylight saving time was in effect (EDT), attempt 6 is during outside of daylight saving (EST). Because of this, the final "turnaround" category should be 111 days, 2 hours, 49 minutes, it is not due to automatic formatting.

| Attempt | Planned | Result | Turnaround | Reason | Decision point | Weather go (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 Nov 2010, 4:40:00 pm | scrubbed[50] | — | technical[51] | 29 Oct 2010, 10:00 am (T-11 hour hold) | 80% | OMS pod leak[51] |

| 2 | 2 Nov 2010, 4:18:00 pm | scrubbed[52] | 0 days 23 hours 38 minutes | technical[52] | (T-11 hour hold) | 70% | OMS pod leak[52] |

| 3 | 3 Nov 2010, 3:52:00 pm | scrubbed[53] | 0 days 23 hours 34 minutes | technical[53] | 2 Nov 2010, 5:40 am (T-11 built-in hold) | 70% | Electrical fault in backup SSME controller. |

| 4 | 4 Nov 2010, 3:29:54 pm | scrubbed[54] | 0 days 23 hours 38 minutes | weather[55][56] | 4 Nov 2010, 6:25 am | 20% | Decision made at pre-tanking weather briefing to reset clock to T-11 hold and delay ~24 hours due to rainy conditions.[55][57] |

| 5 | 5 Nov 2010, 3:04:01 pm | scrubbed | 0 days 23 hours 34 minutes | technical | 5 Nov 2010, 12:00 pm (T-6 hold) | 60% | Hydrogen leak detected at ground umbilical carrier plate (GUCP)[58] |

| 6 | 24 Feb 2011, 4:53:24 pm | success | 111 days 1 hour 49 minutes | 90% | The clock was held at T-5 minutes to allow time to resolve a computer issue at the Range Safety Officer's console. The issue was resolved and the clock restarted in time to allow Discovery to launch with just two seconds left in the launch window.[59][60] |

Mission timeline

[edit]- Section source: NASA Press Kit[61] and NASA TV Live[2] The original nominal mission of twelve days was eventually extended by two days, one at a time.

February 24 (Flight Day 1 – Launch)

[edit]Space Shuttle Discovery successfully lifted off from Kennedy Space Center's Launch Pad 39A at 16:53:24 EST on February 24, 2011. Liftoff was initially set for 16:50:24 EST, but was delayed for 3 minutes by a minor glitch in a computer system used by the Range Safety Officer (RSO) for the Eastern Range. Once Discovery was cleared for launch, it took 8 minutes and 34 seconds to reach orbit. At approximately four minutes into the flight, a piece of foam was seen breaking away from the External Tank. This foam was deemed not to be a threat, since it was liberated after the shuttle had left Earth's atmosphere. During Discovery's ascent, NASA managers also reported that they saw three more additional instances of foam liberation.[62] These losses also occurred after aerodynamic sensitive times when debris could seriously damage the shuttle, and so were deemed non-threatening. NASA's engineers accounted for the foam losses to a condition called "cryo-pumping". When the external tank is loaded with liquid hydrogen, the air trapped in the foam first liquifies. During the ride into orbit, as the hydrogen level in the tank drops, it warms up and the liquefied air turns back into a gas. The pressure generated due to the state change of hydrogen can cause parts of foam in the tank to come off.[63]

Once on orbit, the crew of STS-133 opened the payload bay doors and activated the Ku band antenna for high-speed communications with Mission Control. While the Ku band antenna was being activated, Alvin Drew and Pilot Eric Boe activated the Shuttle Remote Manipulator System (SRMS), also known as the Canadarm. Later in the day, imagery of the External Tank during launch was downlinked for analysis.[64]

-

The Space Shuttle Discovery rockets into orbit for the final time, 24 February 2011.

-

A STS-133 launch video (2 min 32 s).

-

Discovery lifts off from Launch Pad 39A.

-

Close up of the launch from Pad 39A.

February 25 (Flight Day 2 – OBSS inspection)

[edit]Flight Day 2 saw the crew of Discovery begin their preparations to dock with the International Space Station (ISS). The day started with a firing of the Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engine, called the NC2 burn, to help Discovery catch up to the ISS. Commander Steve Lindsey, Pilot Eric Boe and Mission Specialist Al Drew began the day performing an inspection of the Re-enforced Carbon-Carbon (RCC) panels with the Orbital Boom Sensor System (OBSS). Lindsey and Boe started the inspection on the starboard wing and nose cap, and continued on with the port wing; the whole survey took about six hours to complete. Drew joined up with Michael Barratt and Steve Bowen to checkout and get their two Extravehicular Mobility Units (EMUs) ready for the two spacewalks that would be conducted during the mission. Later in the day, the crew checked out the rendezvous tools to ensure they were operational. At the end of the day, another OMS engine firing, known as the NC3 burn, took place.[65]

February 26 (Flight Day 3 – ISS rendezvous)

[edit]The orbiter docked to the ISS on Flight Day 3, marking the 13th time Discovery had visited the ISS. The docking occurred on time at 19:14 UTC. A hard mate between the two vehicles was delayed by about 40 minutes because of relative motion between the station and shuttle, thus putting the crew behind the timeline for the day. The hatches were finally opened at 21:16 UTC, and the Expedition 26 crew greeted the crew of STS-133.[66] After the welcome ceremony and safety briefing, the crew's main task of the day was to transfer the ExPRESS Logistics Carrier 4 (ELC-4). ELC-4 was taken out of Discovery's payload bay by the Space Station Remote Manipulator (SSRMS), also known as Canadarm2, which was operated by Nicole Stott and Michael Barratt. The SSRMS handed it to the Space Shuttle Remote Manipulator System (SSRMS), which was being controlled by Boe and Drew, while the SSRMS moved to the Mobile Base System (MBS). Once there, the SSRMS took ELC-4 back from the SSRMS, and installed it at its location on the S3 truss location. ELC-4 was installed in its final location at 03:22 UTC on February 27.[67] While the robotic transfer was going on, Bowen and Lindsey were transferring items that were needed for Flight Day 4 and the spacewalk on Flight Day 5.

-

A view of the nose, the forward underside and crew cabin of Discovery during the Rendezvous Pitch Maneuver.

-

A view of the aft portion of Discovery's main engines, part of the payload bay, vertical stabilizer and Orbital Maneuvering System pods during the RPM.

-

Video of the RPM.

-

Discovery shortly after docking with the International Space Station on 26 February 2011.

-

The docked Discovery and Dextre are featured in this photograph.

February 27 (Flight Day 4)

[edit]On Flight Day 4, Stott and Barratt grappled the Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS) using the Canadarm2 and removed it from the starboard sill of Discovery's payload bay. Once it was grappled and out of the payload bay, the Shuttle Remote Manipulator System grappled the end of the OBSS and took a handoff from the Canadarm2. The OBSS was grappled by the space station arm, because the SRMS could not reach it due to clearance issues, and it needed to be moved out of the way so that the Permanent Multipurpose Module (PMM) could be removed from the payload bay. After the OBSS handoff, the entire STS-133 crew was joined by ISS Expedition 26 commander Scott Kelly and flight engineer Paolo Nespoli for a series of in-flight media interviews. The interviews were conducted with the Weather Channel, WBZ radio in Boston, Massachusetts, WSB-TV in Atlanta, Georgia, and WBTV in Charlotte, North Carolina.[68] The crew also completed more cargo transfers to and from the ISS. Throughout the day, Drew and Bowen prepared tools that they would use on their spacewalk on Flight Day 5. Later in the day, they were joined by the shuttle crew and ISS commander Kelly and Flight Engineer Nespoli, for a review of the spacewalk procedures. After the review, Bowen and Drew donned oxygen masks and entered the crew lock of the Quest airlock for the standard pre-spacewalk campout. The airlock was lowered to 10.2 psi for the night. This was done to help the spacewalkers purge nitrogen from their blood and help prevent decompression sickness, also known as the bends.[69]

February 28 (Flight Day 5 – EVA 1)

[edit]Steve Bowen and Alvin Drew performed the mission's first extra-vehicular activity (EVA), or spacewalk, on Flight Day 5. After waking up at 06:23 EST, the crew immediately began EVA preparations.[70] A conference was held between the crew of the station and Mission Control at about 08:20 EST, followed by further EVA preparation work, including the depressurization of the airlock. Bowen and Drew switched their spacesuits to internal battery power at 10:46 EST, marking the beginning of EVA 1.[70]

During the EVA, Bowen and Drew installed a power cable linking the Unity and Tranquility modules in order to provide a contingency power source, should it become required. They then moved a failed ammonia pump, which was replaced in August 2010, from its temporary location to the External Stowage Platform 2. Later, operations with the SSRMS robotic arm were delayed to due technical problems with the robotic control station in the Cupola module.[70]

After installing a wedge under a camera on the S3 truss to provide clearance from the newly installed ExPRESS Logistics Carrier-2, performing a Japanese experiment called "Message in a Bottle" to collect a sample of vacuum, and other minor tasks, the EVA ended after six hours and 34 minutes at 17:20 EST.

-

Bowen and Drew (partially obscured at centre) during EVA 1.

-

Bowen and Drew during EVA 1.

March 1 (Flight Day 6 – PMM installation)

[edit]Flight Day 6 saw the installation of the Leonardo Permanent Multipurpose Module (PMM) to the nadir, or Earth-facing, port of the station's Unity module. Once the installation was complete, the external outfitting of Leonardo, to integrate it into the ISS as a permanent module, was begun. Bowen and Drew conducted the procedure review for the mission's second spacewalk, before beginning their pre-EVA campout in the Quest airlock.

March 2 (Flight Day 7 – EVA 2)

[edit]Bowen and Drew conducted STS-133's second EVA on Flight Day 7. Drew removed thermal insulation from a platform, while Bowen swapped out an attachment bracket on the Columbus module. Bowen then installed a camera assembly on the Dextre robot and removed insulation from Dextre's electronics platform. Drew installed a light on a cargo cart and repaired some dislodged thermal insulation from a valve on the truss. Meanwhile, the ISS and shuttle crew entered the Leonardo PMM to commence the internal outfitting of the module.

March 3 (Flight Day 8)

[edit]On Flight Day 8, the transfer of the Leonardo PMM's cargo to the interior of the ISS began. The crew also received some off-duty time on this day.

March 4 (Flight Day 9)

[edit]On Flight Day 9, the equipment used on Drew and Bowen's spacewalk was reconfigured. A joint crew news conference was also conducted via satellite, after which the crew received more off-duty time.

March 5 (Flight Day 10)

[edit]The internal outfitting of the Leonardo PMM continued on Flight Day 10.[71] Furthermore, a photo shoot of the ISS with multiple spacecraft docked was considered, but rejected by mission planners.[71][72]

March 6 (Flight Day 11)

[edit]As well as the continued outfitting of the Leonardo Permanent Multipurpose Module,[71] a checkout of Discovery's rendezvous tools was conducted on Flight Day 11, before the shuttle crew said their farewells to the ISS crew, exited the station and sealed the hatch between the orbiter and the ISS. The installation of a center-line camera was also conducted on this day.

March 7 (Flight Day 12 – Undocking)

[edit]Discovery conducted its final undocking from the ISS on Flight Day 12, and its last fly-around preceded the final separation from the station. A late inspection of Discovery's Thermal Protection System was conducted using the OBSS, before the OBSS was berthed.

March 8 (Flight Day 13)

[edit]The crew of Discovery stowed their equipment in the sle's cabin before conducting a checkout of the flight control system and a hot-fire test of the reaction control system. A final deorbit preparation briefing was carried out before the shuttle's Ku band antenna was stowed.

March 9 (Flight Day 14 – Re-entry and landing)

[edit]On the final day of the mission, Discovery's crew carried out further deorbit preparations, and closed the shuttle's payload bay doors. A successful deorbit burn and re-entry ended with Discovery landing at Kennedy Space Center's Shuttle Landing Facility for the final time on March 9, 2011, at 11:58:14 EST. The shuttle was retired at wheel-stop. It was the final shuttle landing to occur in daylight, the remaining two missions landed at night.

-

Space Shuttle Discovery lands for the final time, at the Shuttle Landing Facility on 9 March 2011.

-

A video recording of the STS-133 landing.

(2 min 30 s)

Spacewalks

[edit]Two spacewalks (EVAs) were conducted during the mission.[73]

| EVA | Spacewalkers | Start (UTC) | End (UTC) | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVA 1 | Steve Bowen Alvin Drew |

February 28, 2011 15:46 |

February 28, 2011 22:20 |

6 hours 34 minutes |

| Drew and Bowen installed a power extension cable between the Unity and Tranquility nodes to provide a contingency power source should it be required. The spacewalkers then moved the failed ammonia pump module that was replaced in August from its temporary location to the External Stowage Platform 2 adjacent to the Quest airlock. Drew and Bowen then installed a wedge under a camera on the S3 truss to provide clearance from the newly installed ELC-4. They next replaced a guide for the rail cart system used for moving the station robotic arm along the truss. The guides had been removed when astronauts were performing work on the station's starboard Solar Alpha Rotary Joint (SARJ), which rotates the solar arrays to track the sun. The final task was to "fill" a special bottle with the vacuum of space for a Japanese education payload. The bottle will be part of a public museum exhibit. | ||||

| EVA 2 | Steve Bowen Alvin Drew |

March 2, 2011 15:42 |

March 2, 2011 21:56 |

6 hours 14 minutes |

| Drew removed thermal insulation from a platform, while Bowen swapped out an attachment bracket on the Columbus module. Bowen then installed a camera assembly on the Dextre robot and removed insulation from Dextre's electronics platform. Drew installed a light on a cargo cart and repaired some dislodged thermal insulation from a valve on the truss. | ||||

Wake-up calls

[edit]NASA began a tradition of playing music to astronauts during the Gemini program, and first used music to wake up a flight crew during Apollo 15. Each track is specially chosen, often by the astronauts' families, and usually has a special meaning to an individual member of the crew, or is applicable to their daily activities.[74]

NASA opened the selection process to the public for the first time for STS-133. The public was invited to vote on two songs used to wake up astronauts on previous missions to wake up the STS-133 crew.[75]

| Flight Day | Song | Artist | Played for |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 2 | "Through Heaven's Eyes" | Brian Stokes Mitchell | Michael R. Barratt |

| Day 3 | "Woody's Roundup" | Riders in the Sky | Alvin Drew |

| Day 4 | "Java Jive" | The Manhattan Transfer | Steven Lindsey |

| Day 5 | "Oh What a Beautiful Morning" | Davy Knowles & Back Door Slam | Nicole Stott |

| Day 6 | "Happy Together" | The Turtles | Stephen Bowen |

| Day 7 | "Speed of Sound" | Coldplay | Eric Boe |

| Day 8 | "City of Blinding Lights" | U2 | STS-133 Crew |

| Day 9 | "The Ritual/Ancient Battle/2nd Kroykah" | Gerald Fried - (Composer) | STS-133 Crew |

| Day 10 | "Ohio (Come Back to Texas)" | Bowling for Soup | STS-133 Crew |

| Day 11 | "Spaceship Superstar" | Prism | STS-133 Crew |

| Day 12 | Theme to "Star Trek" | Voice-over by William Shatner Song by Alexander Courage |

STS-133 Crew |

| Day 13 | "Blue Sky" (Live) | Big Head Todd and the Monsters | STS-133 Crew |

| Day 14 | "Coming Home" | Gwyneth Paltrow | STS-133 Crew |

See also

[edit]- 2011 in spaceflight

- List of human spaceflights

- List of International Space Station spacewalks

- List of Space Shuttle missions

- List of spacewalks 2000–2014

- Space Shuttle Discovery

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ^ "STS-133 Press Kit" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 6, 2010. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- ^ a b "NASA TV "Live Events, Mission Coverage" [STS-133]". NASA TV. February 24, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "Twitter / NASA". NASA. February 24, 2011. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- ^ "Discovery in Orbit". NASA. February 24, 2011. Archived from the original on October 16, 2009. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e McDowell, Jonathan. "Satellite Catalog". Jonathan's Space Page. Retrieved May 28, 2013.

- ^ NASA (September 24, 2009). "Consolidated Launch Manifest". NASA. Archived from the original on March 7, 2009. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- ^ NASA (October 14, 2009). "NASA's Shuttle and Rocket Missions". NASA. Retrieved October 15, 2009.

- ^ "Last Flight of Space Shuttle Discovery STS-133". Outer Space Universe. February 19, 2011. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ Gebhardt, Chris (August 5, 2009). "STS-133 refined to a five crew, one EVA mission – will leave MPLM on ISS". NASAspaceflight.com.

- ^ NASA (February 26, 2010). "NASA and Italian Space Agency Find New Use for Module". NASA. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- ^ Chris Gebhardt (October 6, 2010). "PMM Leonardo: The Final Permanent U.S. Module for the ISS". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ^ Stevens, Tim (April 14, 2010). "NASA and GM's humanoid Robonaut2 blasting into space this September".

- ^ Ron Diftler (November 18, 2010). "Robonaut 2 (R2) Overview" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ "Spaceflight mission report: STS-133". www.spacefacts.de. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ Chris Bergin (July 19, 2010). "STS-133: SpaceX's DragonEye set for late installation on Discovery". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ^ "Student Signatures in Space (S3)". Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2010.

- ^ "STS-133: What's Going Up". 1 November 2010. NASA.

- ^ "NASA Assigns Crew for Final Space Shuttle Mission". NASA. Archived from the original on November 22, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "CBSNews – STS-133 Quick Look 1". CBS News. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ a b "STS-133 launch remains on track as Bowen replaces the injured Kopra". nasaspaceflight.com. January 19, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ^ "Active Astronauts". NASA. February 11, 2015.

- ^ a b Tariq Malik (September 18, 2009). "NASA Reveals Crew for Last Scheduled Shuttle Mission". SPACE.com. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- ^ a b Chris Bergin (October 15, 2010). "STS-133: TCDT completed – Engineers troubleshooting leaky flight cap". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- ^ Matthew Travis (October 28, 2010). "All-Veteran Crew Flies To KSC For Discovery's Final Launch". SpaceflightNews.net. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ a b "Space veteran to sub for injured astronaut". USA Today. January 20, 2011. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ^ Robert Z. Pearlman (September 9, 2010). "Space shuttle Discovery departs hangar for final flight". CollectSPACE. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ^ James Dean (September 8, 2010). "Shuttle rollover delayed by water leak". Florida TODAY. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ^ vertical flow refers to the period of time between rollout from the Shuttle Processing Facility and launch.

- ^ ATK. "STS-133 SRB Use History" (PDF). Spaceflight Now.

- ^ Chris Bergin (September 10, 2010). "STS-133: Engineers complete repair on Discovery following ET mate issue". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ^ William Harwood (September 11, 2010). "Shuttle Discovery finally bolted to external tank". Spaceflight NOW. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ^ Robert Z. Pearlman (September 21, 2010). "Space shuttle Discovery makes last trip to launch pad". Collect SPACE. Retrieved September 22, 2010.

- ^ William Harwood (October 18, 2010). "Technicians working on tiny fuel leak in Discovery pod". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- ^ Chris Bergin (October 18, 2010). "STS-133: Discovery to undergo unique leak repair to avoid rollback". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- ^ Chris Bergin (October 22, 2010). "STS-133: Crossfeed flange seal R&R complete – OMS reload in work". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved October 30, 2010.

- ^ William Harwood (October 26, 2010). "Shuttle Discovery cleared for blastoff next Monday". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved October 30, 2010.

- ^ William Harwood (November 2, 2010). "Shuttle engine controller glitch being assessed". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- ^ Chris Bergin (November 2, 2010). "STS-133: Launch delayed at least 24 hours due to Main Engine Controller issue". NASApspaceflight.com.

- ^ William Harwood (November 12, 2010). "Apparent seal problem found in leaking shuttle vent line". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- ^ Chris Bergin (November 11, 2010). "STS-133: Closing in on GUCP root cause – ET repair at pad still positive". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ^ "Space Flight Awareness Silver Snoopy Award". NASA. October 7, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Chris Bergin (November 12, 2010). "STS-133: More cracks found on ET-137 as managers debate forward plan". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- ^ William Harwood (November 15, 2010). "Fourth crack found on shuttle Discovery's external tank". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- ^ "Underlying metal cracks found on Discovery's tank". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- ^ Chris Bergin and Chris Gebhardt (November 24, 2010). "STS-133: NASA managers decide to slip to a NET December 17 target". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- ^ "Discovery's launch delayed until at least mid-December". Spaceflight Now. November 24, 2010.

- ^ Denis Chow (November 24, 2010). "Latest Launch Delay May Push Shuttle Discovery's Final Flight into Christmas". SPACE.com. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (February 18, 2011). "STS-133: FRR approves Discovery's launch for next Thursday". Spaceflight Now.

- ^ NASA.gov/multimedia/nasatv/: per NASA Live TV broadcast

- ^ William Harwood. "Shuttle Discovery cleared for blastoff next Monday". SpaceflightNow.com. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ a b STS-133: Pressurization issues delay launch by at least a day

- ^ a b c "Countdown to Start Sunday for Targeted Launch Wednesday". NASA. Retrieved October 30, 2010.

- ^ a b "Shuttle Wont Launch Wednesday". Chicago Tribune. November 2, 2010. Archived from the original on November 7, 2010. Retrieved November 2, 2010.

- ^ "STS-133 coverage". Spaceflight now.

- ^ a b "Discover scrubbed". Spaceflight.com. November 4, 2010.

- ^ Electrical Issue Delays Discovery Launch Another 24 HoursArchived November 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Weather Forces Another Delay For Discovery LaunchArchived November 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hydrogen Leak Forces Scrub Of Discovery Launch Archived November 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ STS-133 countdown

- ^ "STS-133 Launches on Historic Final Mission for Shuttle Discovery". February 24, 2011.

- ^ "NASA Official STS-133 Press Kit" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 6, 2010. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- ^ "Crew checks Discovery's heat shield, spacesuits". CollectSPACE. February 25, 2011. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

- ^ William Harwood (February 25, 2011). "'Cryopumping' likely cause of Discovery tank foam loss". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

- ^ Chris Bergin & Chris Gebhardt (February 24, 2011). "Discovery launches after dramatic range fix late in countdown". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ Chris Bergin (February 25, 2011). "STS-133 – Healthy Discovery completes FD2 inspections on RCC panels". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

- ^ "STS-133 MCC Status Report No. 05". NASA. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ Bill Harwood. "Discovery pulls into port for her final space station visit". CBS News. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ "STS-133 MCC Status Report No. 07". NASA. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ Bill Harwood. "Astronauts having on busy Sunday aboard the station". CBS News/SpaceflightNow. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ a b c Gebhardt, Chris (February 28, 2011). "STS-133: EVA-1 completed; Endeavour Rolls to VAB one last time". nasaspaceflight.com. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ a b c Harwood, William (February 28, 2011). "Mission extended one day". CBS News. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ Harwood, William (March 1, 2011). "Proposed Ultimate Space Station Photo Op Rejected". Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ Chris Gebhardt (June 11, 2010). "STS-133: Three Flight Days and two EVAs added to Discovery's mission". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ^ Fries, Colin (August 2, 2005). "Chronology of Wakeup Calls" (PDF). NASA. pp. 74–76. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 20, 2023. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ "NASA's Space Rock". NASA. Archived from the original on October 10, 2010.

External links

[edit]- NASA's Space Shuttle page

- NASA's STS-133 mission page

- Watch STS-133 launch video / ICARE Live

- Twitter Feed of the events for sts-133

- STS-133 Flight Day Journal – collectSPACE

- STS-133 Preflight Briefings Video – SpaceflightNews.net / NASA TV

- Behind the Scenes With Astronaut Mike Massimino – SpaceflightNews.net / NASA TV

- STS-133 preflight crew interview videos – SpaceflightNews.net / NASA TV

- 3D video of ISS and STS-133 Archived March 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, from Thierry Legault as observed from the Earth's surface

- Space Shuttle Discovery STS-133 Astronauts Interviewed for BBC Breakfast / BBC TV

- Video: STS-133 Space Shuttle Crew Ready For Discovery's Final Mission Part 1 – SpaceflightNews.net / YouTube

- Video: STS-133 Space Shuttle Crew Ready For Discovery's Final Mission Part 2 – SpaceflightNews.net / YouTube

- Video: STS-133 – Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test Crew Q & A Session at Launch Pad 39A Part 1 – SpaceflightNews.net / YouTube

- Video: STS-133 – Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test Crew Q & A Session at Launch Pad 39A Part 2 – SpaceflightNews.net / YouTube

- Video: STS-133 Discovery astronauts take part in countdown dress rehearsal Part 1 – SpaceflightNews.net / YouTube

- Video: STS-133 Discovery astronauts take part in countdown dress rehearsal Part 2 – SpaceflightNews.net / YouTube

- Video: STS-133 Crew Arrives For Shuttle Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test – SpaceflightNews.net / YouTube

- Video: STS-133 Launch Seen From Airplane – STS-133 launch seen from airplane / YouTube

- nasatech.net STS-133 Mission Page with spherical panoramas on the pad, in the VAB and the payload in the SSPF[permanent dead link]

| January | |

|---|---|

| February | |

| March | |

| April | |

| May | |

| June | |

| July |

|

| August |

|

| September |

|

| October | |

| November |

|

| December |

|

Launches are separated by dots ( • ), payloads by commas ( , ), multiple names for the same satellite by slashes ( / ). Crewed flights are underlined. Launch failures are marked with the † sign. Payloads deployed from other spacecraft are (enclosed in parentheses). | |

Space Shuttle Discovery (OV-103) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Completed flights | ||

| Status |

| |

| On display | ||

| Related |

| |

| 1998–2004 |

| |

|---|---|---|

| 2005–2009 | ||

| 2010–2014 | ||

| 2015–2019 |

| |

| Since 2020 |

| |

| Future | ||

| Individuals | ||

| Vehicles |

| |

| ||

| Completed (crews) |

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancelled | |||||||||||

| Orbiters | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||