| Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary | |

|---|---|

A famous treatment in Western art, Titian's Assumption, 1516–1518 | |

| Also called |

|

| Observed by | |

| Type | Christian |

| Significance | The bodily taking up of Mary, the mother of Jesus into Heaven |

| Observances | Attending Mass or service |

| Date |

|

| Frequency | Annual |

The Assumption of Mary is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church. Pope Pius XII defined it on 1 November 1950 in his apostolic constitution Munificentissimus Deus as follows:

We pronounce, declare, and define it to be a divinely revealed dogma: that the Immaculate Mother of God, the ever-Virgin Mary, having completed the course of her earthly life, was assumed body and soul into heavenly glory.

— Pope Pius XII, Munificentissimus Deus, 1950[2]

The declaration was built upon the 1854 dogma of the Immaculate Conception of Mary, which declared that Mary was conceived free from original sin, and both have their foundation in the concept of Mary as the Mother of God.[3] It leaves open the question of whether Mary died or whether she was raised to eternal life without bodily death.[4]

The equivalent belief (which is not held as dogma) in the Eastern Orthodox Church is the Dormition of the Mother of God or the "Falling Asleep of the Mother of God".

The word 'assumption' derives from the Latin word assūmptiō, meaning 'taking up'.

Mary's assumption highlights the Catholic belief in the resurrection of both body and flesh. Pope Pius expressed in his encyclical Munificentissimus Deus the hope that the belief in the bodily assumption of the virgin Mary into heaven "will make our belief in our own resurrection stronger and render it more effective".[5][6]

In some versions of the assumption narrative, the assumption is said to have taken place in Ephesus, in the House of the Virgin Mary. This is a much more recent and localized tradition. The earliest traditions say that Mary's life ended in Jerusalem (see Tomb of the Virgin Mary). By the 7th century, a variation emerged, according to which one of the apostles, often identified as Thomas the Apostle, was not present at the death of Mary but his late arrival precipitates a reopening of Mary's tomb, which is found to be empty except for her grave clothes. In a later tradition, Mary drops her girdle down to the apostle from heaven as testament to the event.[7] This incident is depicted in many later paintings of the Assumption.

Teaching of the Assumption of Mary became widespread across the Christian world, having been celebrated as early as the 5th century and having been established in the East by Emperor Maurice around AD 600.[8] John Damascene records the following:

St. Juvenal, Bishop of Jerusalem, at the Council of Chalcedon (451), made known to the Emperor Marcian and Pulcheria, who wished to possess the body of the Mother of God, that Mary died in the presence of all the Apostles, but that her tomb, when opened upon the request of St. Thomas, was found empty; wherefrom the Apostles concluded that the body was taken up to heaven.[9]

Some scholars argue that the Dormition and Assumption traditions can be traced early in church history in apocryphal books, with Shoemaker stating,

Other scholars have similarly identified these two apocrypha as particularly early. For instance, Baldi, Masconi, and Cothenet analyzed the corpus of Dormition narratives using a rather different approach, governed primarily by language tradition rather than literary relations, and yet all agree that the Obsequies (i.e., the Liber Requiei) and the Six Books apocryphon reflect the earliest traditions, locating their origins in the second or third century.[10]

Scholars of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum "argued that during or shortly after the apostolic age a group of Jewish Christians in Jerusalem preserved an oral tradition about the end of the Virgin's life". Thus, by pointing to oral tradition, they argued for the historicity of the assumption and Dormition narratives. However, Shoemaker notes they fail to take into account the various "strikingly diverse traditions" that the Assumption seems to come from, mainly, "a great variety of original types", rather than "a single unified tradition". Regardless, Shoemaker states even those scholars note "belief in the Virgin's Assumption is the final dogmatic development, rather than the point of origin, of these traditions".[11]

According to Stephen J. Shoemaker, the first known narrative to address the end of Mary's life and her assumption is the apocryphal third- and possibly second-century Liber Requiei Mariae ("Book of Mary's Repose").[12] Shoemaker asserts that "this earliest evidence for the veneration of Mary appears to come from a markedly heterodox theological milieu".[13]

Other early sources, less suspect in their content, also contain references to the Assumption. "The Dormition/Assumption of Mary" (attributed to John the Theologian or "Pseudo-John"), another anonymous narrative, is possibly dated to the fourth century, but is dated by Shoemaker as later.[14] The "Six Books Dormition Apocryphon", dated to the early fourth century,[13] likewise speaks of the Assumption. "Six Books Dormition Apocryphon" was perhaps associated with the Collyridians who were condemned by Epiphanius of Salamis "for their excessive devotion to the Virgin Mary".[13]

Shoemaker mentions that "the ancient narratives are neither clear nor unanimous in either supporting or contradicting the dogma" of the assumption.[15]

In accordance with Stephen J. Shoemaker "there is no evidence of any tradition concerning Mary's Dormition and Assumption from before the fifth century. The only exception to this is Epiphanius' unsuccessful attempt to uncover a tradition of the end of Mary's life towards the end of the fourth century."[16] The New Testament is silent regarding the end of her life, the early Christians produced no accounts of her death, and in the late 4th century Epiphanius of Salamis wrote he could find no authorized tradition about how her life ended.[17] Nevertheless, although Epiphanius could not decide on the basis of biblical or church tradition whether Mary had died or remained immortal, his indecisive reflections suggest that some difference of opinion on the matter had already arisen in his time,[18] and he identified three beliefs concerning her end: that she died a normal and peaceful death; that she died a martyr; and that she did not die.[18] Even more, in another text Epiphanius stated that Mary was like Elijah because she never died but was assumed, like him.[19]

Notable later apocrypha that mention the Assumption include De Obitu S. Dominae and De Transitu Virginis, both probably from the 5th century, with further versions by Dionysius the Areopagite, and Gregory of Tours, among others.[20] The Transitus Mariae was considered as apocrypha in a 6th-century work called Decretum Gelasianum,[21] but by the early 8th century the belief was so well established that John of Damascus could set out what had become the standard Eastern tradition, that "Mary died in the presence of the Apostles, but that her tomb, when opened, upon the request of St Thomas, was found empty; wherefrom the Apostles concluded that the body was taken up to heaven."[22]

Euthymiac History, from the sixth century, contains one of the earliest reference to the doctrine of the Assumption of Mary.[23]

The Feast of the Dormition, imported from the East, arrived in the West in the early 7th century, its name changing to Assumption in some 9th century liturgical calendars.[24] In the same century Pope Leo IV (reigned 847–855) gave the feast a vigil and an octave to solemnise it above all others, and Pope Nicholas I (858–867) placed it on a par with Christmas and Easter. In the 12th century, the German nun Elisabeth of Schönau was reportedly granted visions of Mary and her son which had a profound influence on the Western Church's tradition that Mary was assumed in body and soul into Heaven,[24] and Pope Benedict XIV (1740–1758) declared it "a probable opinion, which to deny were impious and blasphemous".[25]

Pope Pius XII, in promulgating Munificentissimus Deus, stated that "All these proofs and considerations of the holy Fathers and the theologians are based upon the Sacred Writings as their ultimate foundation." The pope did not advance any specific text as proof of the doctrine, but one senior advisor, Father Jugie, expressed the view that Revelation 12:1–2 was the chief scriptural witness to the assumption:[26]

And a great sign appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars; and she was with child ...

The symbolism of this verse is based on the Old Testament, where the sun, moon, and eleven stars represent the patriarch Jacob, his wife, and eleven of the twelve tribes of Israel, who bow down before the twelfth star and tribe, Joseph, and verses 2–6 reveal that the woman is an image of the faithful community.[27] The possibility that it might be a reference to Mary's immortality was tentatively proposed by Epiphanius in the 4th century, but while Epiphanius made clear his uncertainty and did not advocate the view, many later scholars did not share his hesitation and its reading as a representation of Mary became popular with certain Roman Catholic theologians.[28]

Many of the bishops cited Genesis 3:15, in which God is addressing the serpent in the Garden of Eden, as the primary confirmation of Mary's assumption:[29]

I will put enmities between thee and the woman, and thy seed and her seed: she shall crush thy head, and thou shalt lie in wait for her heel.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church affirms that the account of the fall in Genesis 3 uses figurative language, and that the fall of mankind, by the seductive voice of the snake in the Bible, represents the fallen angel, Satan.[30] Similarly, the great dragon in Revelation 12 is a representation of Satan, identified with the serpent from the garden who has enmity with the woman. Though the woman in Revelation represents the people of God, faithful Israel and the Church, Mary is considered the Mother of the Church.[31] Therefore, in Catholic thought, there is an association between this heavenly woman and Mary's Assumption.

Some scholars contend that no messianic prophecy was originally intended,[32] that in the Hebrew Bible the serpent is not satanic, and the verse is simply a record of the enmity between mankind and snakes (although a memory of the ancient Canaanite myth of a primordial sea-serpent may stand behind them, albeit at a distance).[33] But although the verse speaks literally about mankind's relationship with snakes, there is also a metaphorical overtone: a door has been opened to a dark power and there is no promise of victory, but rather a warning of ongoing conflict.[34]

Among the many other passages noted by Pope Pius were the following:[29]

On 1 May 1950 Gilles Bouhours (a marian seer) reported to Pius XII a presumed message that the Virgin Mary would have ordered him to communicate to the pope on the dogma of the Assumption of the Holy Virgin Mary. It is said that Pius XII asked God, during the Holy Year of 1950, for a sign that could reassure him that the dogma of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary was actually wanted by God and when Gilles communicated the message to Pius XII, the pope considered this message the hoped-for sign. Six months after the private audience granted to Gilles by the pope, Pius XII himself proclaimed the dogma of the Assumption of body and soul of the Blessed Virgin Mary into Heaven.

Some Catholics believe that Mary died before being assumed, but they believe that she was miraculously resurrected before being assumed (mortalistic interpretation). Others believe she was assumed bodily into Heaven without first dying (immortalistic interpretation).[36][37] Either understanding may be legitimately held by Catholics, with Eastern Catholics observing the Feast as the Dormition. It seems, however, that there is much more evidence for the mortalistic position in the Catholic traditions (liturgy, apocrypha, material culture).[38] It is also worth noting that St. Pope John Paul II expressed the mortalistic position in his public speech.[39]

Many theologians note by way of comparison that in the Catholic Church the Assumption is dogmatically defined, whilst in the Eastern Orthodox tradition the Dormition is less dogmatically than liturgically and mystically defined. Such differences spring from a larger pattern in the two traditions, wherein Catholic teachings are often dogmatically and authoritatively defined – in part because of the more centralized structure of the Catholic Church – whilst in Eastern Orthodoxy many doctrines are less authoritative.[40]

The Latin Catholic Feast of the Assumption is celebrated on 15 August and the Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholics celebrate the Dormition of the Mother of God (or Dormition of the Theotokos, the falling asleep of the Mother of God) on the same date, preceded by a 14-day fasting period. Eastern Christians believe that Mary died a natural death, that her soul was received by Christ upon death, that her body was resurrected after her death and that she was taken up into heaven bodily in anticipation of the general resurrection.

Orthodox tradition is clear and unwavering in regard to the central point [of the Dormition]: the Holy Virgin underwent, as did her Son, a physical death, but her body – like His – was afterwards raised from the dead and she was taken up into heaven, in her body as well as in her soul. She has passed beyond death and judgement and lives wholly in the Age to Come. The Resurrection of the Body ... has in her case been anticipated and is already an accomplished fact. That does not mean, however, that she is dissociated from the rest of humanity and placed in a wholly different category: for we all hope to share one day in that same glory of the Resurrection of the Body that she enjoys even now.[41]

Views differ within Protestantism, with those with a theology closer to Catholicism sometimes believing in a bodily assumption whilst most Protestants do not.

The Feast of the Assumption of Mary was retained by the Lutheran Church after the Reformation.[42] Evangelical Lutheran Worship designates August 15 as a lesser festival named "Mary, Mother of Our Lord" while the current Lutheran Service Book formally calls it "St. Mary, Mother of our Lord".[42]

Within Anglicanism the Assumption of Mary is accepted by some, rejected by others, or regarded as adiaphora ("a thing indifferent").[43] The doctrine effectively disappeared from Anglican worship in 1549, partially returning in Anglo-Catholic tradition during the 20th century under different names. A Marian feast on 15 August is celebrated by the Church of England as a non-specific feast of the Blessed Virgin Mary, a feast called by the Scottish Episcopal Church simply "Mary the Virgin",[44][45][46] and in the US-based Episcopal Church it is observed as the feast of "Saint Mary the Virgin: Mother of Our Lord Jesus Christ",[47] while other Anglican provinces have a feast of the Dormition[44] – the Anglican Church of Canada, for instance, marks the day as the "Falling Asleep of the Blessed Virgin Mary".[48]

The Anglican-Roman Catholic International Commission, which seeks to identify common ground between the two communions, released in 2004 a non-authoritative declaration meant for study and evaluation, the "Seattle Statement"; this "agreed statement" concludes that "the teaching about Mary in the two definitions of the Assumption and the Immaculate Conception, understood within the biblical pattern of the economy of hope and grace, can be said to be consonant with the teaching of the Scriptures and the ancient common traditions".[49]

The Protestant reformer Heinrich Bullinger believed in the assumption of Mary. His 1539 polemical treatise against idolatry[50] expressed his belief that Mary's sacrosanctum corpus ("sacrosanct body") had been assumed into heaven by angels:

Hac causa credimus ut Deiparae virginis Mariae purissimum thalamum et spiritus sancti templum, hoc est, sacrosanctum corpus ejus deportatum esse ab angelis in coelum.[51] |

For this reason we believe that the Virgin Mary, Begetter of God, the most pure bed and temple of the Holy Spirit, that is, her most holy body, was carried to heaven by angels.[52] |

Orthodox Christians fast for fourteen days before the Feast of the Assumption of Mary, including abstinence from sexual relations.[53] Fasting in the Orthodox Churches generally consists of abstinence from certain food groups; during the Dormition fast, one observes a strict fast on weekdays, with wine and oil allowed on weekends and, additionally, fish on the Transfiguration (August 6).[54]

The Assumption is important to many Christians, especially Catholics and Orthodox, as well as many Lutherans and Anglicans, as the Virgin Mary's heavenly birthday (the day that Mary was received into Heaven). Belief about her acceptance into the glory of Heaven is seen by some Christians as the symbol of the promise made by Jesus to all enduring Christians that they too will be received into paradise. The Assumption of Mary is symbolised in the Fleur-de-lys Madonna.

The present Italian name of the holiday, Ferragosto, may derive from the Latin name, Feriae Augusti ("Holidays of the Emperor Augustus"),[55] since the month of August took its name from the emperor. The feast was introduced by Bishop Cyril of Alexandria in the 5th century. In the course of Christianization, he put it on 15 August. In the middle of August, Augustus celebrated his victories over Marcus Antonius and Cleopatra at Actium and Alexandria with a three-day triumph. The anniversaries (and later only 15 August) were public holidays from then on throughout the Roman Empire.[56]

The Solemnity of the Assumption on 15 August was celebrated in the Eastern Church from the 6th century. The Western Church adopted this date as a Holy Day of Obligation to commemorate the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, a reference to the belief in a real, physical elevation of her sinless soul and incorrupt body into Heaven.

Assumption Day on 15 August is a nationwide public holiday in Andorra, Austria, Belgium, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chile, Republic of Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Croatia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cyprus, East Timor, France, Gabon, Greece, Georgia, Republic of Guinea, Haiti, Italy, Lebanon, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Republic of North Macedonia, Madagascar, Malta, Mauritius, Republic of Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro (Albanian Catholics), Paraguay, Poland (coinciding with Polish Army Day), Portugal, Romania, Rwanda, Senegal, Seychelles, Slovenia, Spain, Syria, Tahiti, Togo, and Vanuatu;[57] and was also in Hungary until 1948.

It is also a public holiday in parts of Germany (parts of Bavaria and Saarland) and Switzerland (in 14 of the 26 cantons). In Guatemala, it is observed in Guatemala City and in the town of Santa Maria Nebaj, both of which claim her as their patron saint.[58] Also, this day is combined with Mother's Day in Costa Rica and parts of Belgium.

Prominent Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox countries in which Assumption Day is an important festival but is not recognized by the state as a public holiday include the Czech Republic, Ireland, Mexico, the Philippines and Russia. In Bulgaria, the Feast of the Assumption is the biggest Eastern Orthodox Christian celebration of the Holy Virgin. Celebrations include liturgies and votive offerings. In Varna, the day is celebrated with a procession of a holy icon, and with concerts and regattas.[59]

In many places, religious parades and popular festivals are held to celebrate this day. In Canada, Assumption Day is the Fête Nationale of the Acadians, of whom she is the patroness saint. Some businesses close on that day in heavily francophone parts of New Brunswick, Canada. The Virgin Assumed in Heaven is also patroness of the Maltese Islands and her feast, celebrated on 15 August, apart from being a public holiday in Malta is also celebrated with great solemnity in the local churches especially in the seven localities known as the Seba' Santa Marijiet. The Maltese localities which celebrate the Assumption of Our Lady are: Il-Mosta, Il-Qrendi, Ħal Kirkop, Ħal Għaxaq, Il-Gudja, Ħ'Attard, L-Imqabba and Victoria. The hamlet of Praha, Texas, holds a festival during which its population swells from approximately 25 to 5,000 people.

In Anglicanism and Lutheranism, the feast is now often kept, but without official use of the word "Assumption". In Eastern Orthodox churches following the Julian Calendar, the feast day of Assumption of Mary falls on 28 August.

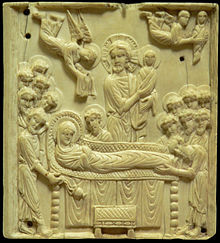

The earliest known use of the Dormition is found on a sarcophagus in the crypt of a church in Zaragoza in Spain dated c. 330.[20] The Assumption became a popular subject in Western Christian art, especially from the 12th century, and especially after the Reformation, when it was used to refute the Protestants and their downplaying of Mary's role in salvation.[60] Angels commonly carry her heavenward where she is to be crowned by Christ, while the Apostles below surround her empty tomb as they stare up in awe.[60] Caravaggio, the "father" of the Baroque movement, caused a stir by depicting her as a decaying corpse, quite contrary to the doctrine promoted by the church;[61] more orthodox examples include works by El Greco, Rubens, Annibale Carracci, and Nicolas Poussin, the last replacing the Apostles with putti throwing flowers into the tomb.[60]

Many early Lutherans retained the Feast of the Assumption in the liturgical calendar, while recognizing it as a speculation rather than a dogma. However, Pope Pius XII dogmatized this belief in 1950 in his decree Munificentissimus Dei (sic), thus imposing it as doctrine upon Roman Catholics. ... Today's feast is described in Lutheran Service Book as 'St. Mary, Mother of our Lord'.

There is no direct testimony in Scripture concerning the end of Mary's life. However, certain passages give instances of those who follow God's purposes faithfully being drawn into God's presence. Moreover, these passages offer hints or partial analogies that may throw light on the mystery of Mary's entry into glory.

| Family | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life |

| ||||||||||||||

| Mariology |

| ||||||||||||||

| Veneration |

| ||||||||||||||

Liturgical year of the Catholic Church | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

History of the Catholic Church | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | |||||||||

| Early Church (30–325/476) |

| ||||||||

| Early Middle Ages | |||||||||

| High Middle Ages |

| ||||||||

| Late Middle Ages | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| 19th century | |||||||||

| 20th century |

| ||||||||

| 21st century | |||||||||

| History (Timeline Ecclesiastical Legal) |

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theology (Bible Tradition Catechism) |

| ||||||||||||

| Philosophy | |||||||||||||

| Saints | |||||||||||||

| Organisation (Hierarchy Canon law Laity Precedence By country) |

| ||||||||||||

| Culture | |||||||||||||

| Media | |||||||||||||

| Religious orders, institutes, societies |

| ||||||||||||

| Associations of the faithful | |||||||||||||

| Charities | |||||||||||||