| |

| Geographical range | Europe |

|---|---|

| Period | Late Bronze Age, Early Iron Age |

| Dates | 1200 – 450 BC Hallstatt A (1200 – 1050 BC); Hallstatt B (1050 – 800 BC); Hallstatt C (800 – 650 BC); Hallstatt D (620 – 450 BC) |

| Type site | Hallstatt |

| Preceded by | Urnfield culture |

| Followed by | La Tène culture |

The Hallstatt culture was the predominant Western and Central European archaeological culture of the Late Bronze Age (Hallstatt A, Hallstatt B) from the 12th to 8th centuries BC and Early Iron Age Europe (Hallstatt C, Hallstatt D) from the 8th to 6th centuries BC, developing out of the Urnfield culture of the 12th century BC (Late Bronze Age) and followed in much of its area by the La Tène culture. It is commonly associated with Proto-Celtic speaking populations.

It is named for its type site, Hallstatt, a lakeside village in the Austrian Salzkammergut southeast of Salzburg, where there was a rich salt mine, and some 1,300 burials are known, many with fine artifacts. Material from Hallstatt has been classified into four periods, designated "Hallstatt A" to "D". Hallstatt A and B are regarded as Late Bronze Age and the terms used for wider areas, such as "Hallstatt culture", or "period", "style" and so on, relate to the Iron Age Hallstatt C and D.

By the 6th century BC, it had expanded to include wide territories, falling into two zones, east and west, between them covering much of western and central Europe down to the Alps, and extending into northern Italy. Parts of Britain and Iberia are included in the ultimate expansion of the culture.

The culture was based on farming, but metal-working was considerably advanced, and by the end of the period long-range trade within the area and with Mediterranean cultures was economically significant. Social distinctions became increasingly important, with emerging elite classes of chieftains and warriors, and perhaps those with other skills. Society is thought to have been organized on a tribal basis, though very little is known about this. Settlement size was generally small, although a few of the largest settlements, like Heuneburg in the south of Germany, were towns rather than villages by modern standards. However, at the end of the period these seem to have been overthrown or abandoned.

Chronology

[edit]According to Paul Reinecke's time-scheme from 1902,[1] the end of the Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age were divided into four periods:

| Bronze Age Central Europe[2] | |

|---|---|

| Bell Beaker | 2600–2200 BC |

| Bz A | 2200–1600 BC |

| Bz B | 1600–1500 BC |

| Bz C | 1500–1300 BC |

| Bz D | 1300–1200 BC |

| Ha A | 1200–1050 BC |

| Ha B | 1050–800 BC |

| Iron Age Central Europe | |

| Hallstatt | |

| Ha C | 800–620 BC |

| Ha D | 620–450 BC |

| La Tène | |

| LT A | 450–380 BC |

| LT B | 380–250 BC |

| LT C | 250–150 BC |

| LT D | 150–1 BC |

| Roman period[3] | |

| B | AD 1–150 |

| C | AD 150–375 |

Bronze Age Urnfield culture:

- HaA (1200–1050 BC)

- HaB (1050-800 BC)

Early Iron Age Hallstatt culture:

- HaC (800-620 BC)

- HaD (620-450 BC)[4]

Paul Reinecke based his chronological divisions on finds from the south of Germany.

Already by 1881 Otto Tischler had made analogies to the Iron Age in the Northern Alps based on finds of brooches from graves in the south of Germany.[5]

Absolute dating

[edit]It has proven difficult to use radiocarbon dating for the Early Iron Age due to the so-called "Hallstatt-Plateau", a phenomenon where radiocarbon dates cannot be distinguished between 750 and 400 BC. There are workarounds however, such as the wiggle matching technique. Therefore, dating in this time-period has been based mainly on Dendrochronology and relative dating.

For the beginning of HaC wood pieces from the Cart Grave of Wehringen (Landkreis Augsburg) deliver a solid dating in 778 ± 5 BC (Grave Barrow 8).[6]

Despite missing an older Dendro-date for HaC, the convention remains that the Hallstatt period begins together with the arrival of the iron ore processing technology around 800 BC.

Relative dating

[edit]HaC is dated according to the presence of Mindelheim-type swords, binocular brooches, harp brooches, and arched brooches.

Based on the quickly changing fashions of brooches, it was possible to divide HaD into three stages (D1-D3). In HaD1 snake brooches are predominant, while in HaD2 drum brooches appear more often, and in HaD3 the double-drum and embellished foot brooches.

The transition to the La Tène period is often connected with the emergence of the first animal-shaped brooches, with Certosa-type and with Marzabotto-type brooches.

Hallstatt type site

[edit]The community at Hallstatt was untypical of the wider, mainly agricultural, culture, as its booming economy exploited the salt mines in the area. These had been worked from time to time since the Neolithic period, and in this period were extensively mined with a peak from the 8th to 5th centuries BC. The style and decoration of the grave goods found in the cemetery are very distinctive, and artifacts made in this style are widespread in Europe. In the mine workings themselves, the salt has preserved many organic materials such as textiles, wood and leather, and many abandoned artifacts such as shoes, pieces of cloth, and tools including miner's backpacks, have survived in good condition.[7]

In 1846, Johann Georg Ramsauer (1795–1874) discovered a large prehistoric cemetery near Hallstatt, Austria (47°33′40″N 13°38′31″E / 47.561°N 13.642°E), which he excavated during the second half of the 19th century. Eventually the excavation would yield 1,045 burials, although no settlement has yet been found. This may be covered by the later village, which has long occupied the whole narrow strip between the steep hillsides and the lake. Some 1,300 burials have been found, including around 2,000 individuals, with women and children but few infants.[8] Nor is there a "princely" burial, as often found near large settlements. Instead, there are a large number of burials varying considerably in the number and richness of the grave goods, but with a high proportion containing goods suggesting a life well above subsistence level. It is now thought that at least most of these were not miners themselves, but from a richer class controlling the mines. [citation needed]

Finds at Hallstatt extend from about 1200 BC until around 500 BC, and are divided by archaeologists into four phases:

Hallstatt A–B (1200–800 BC) are part of the Bronze Age Urnfield culture. In this period, people were cremated and buried in simple graves. In phase B, tumulus (barrow or kurgan) burial becomes common, and cremation predominates. The "Hallstatt period" proper is restricted to HaC and HaD (800–450 BC), corresponding to the early European Iron Age. Hallstatt lies in the area where the western and eastern zones of the Hallstatt culture meet, which is reflected in the finds from there.[9] Hallstatt D is succeeded by the La Tène culture.

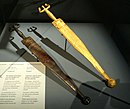

Hallstatt C is characterized by the first appearance of iron swords mixed amongst the bronze ones. Inhumation and cremation co-occur. For the final phase, Hallstatt D, daggers, almost to the exclusion of swords, are found in western zone graves ranging from c. 600–500 BC.[10] There are also differences in the pottery and brooches. Burials were mostly inhumations. Halstatt D has been further divided into the sub-phases D1–D3, relating only to the western zone, and mainly based on the form of brooches.[10]

Major activity at the site appears to have finished about 500 BC, for reasons that are unclear. Many Hallstatt graves were robbed, probably at this time. There was widespread disruption throughout the western Hallstatt zone, and the salt workings had by then become very deep.[11] By then the focus of salt mining had shifted to the nearby Hallein Salt Mine, with graves at Dürrnberg nearby where there are significant finds from the late Hallstatt and early La Tène periods, until the mid-4th century BC, when a major landslide destroyed the mineshafts and ended mining activity.[12]

Much of the material from early excavations was dispersed,[8] and is now found in many collections, especially German and Austrian museums, but the Hallstatt Museum in the town has the largest collection.

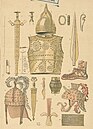

- Finds from the Hallstatt site

-

Bronze vessel with cow and calf decoration

-

Wood and leather carrying pack from the mine

-

Bronze artefacts from Hallstatt

-

Textile fragment from the salt mine

-

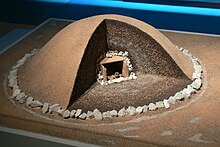

Hallstatt grave reconstruction

-

Preserved wood stairs from the Hallstatt salt mine

-

Ha C axehead, Hallstatt

-

Fibula brooch with animal figures

-

Dagger

-

Finds from Hallstatt

-

Finds from the Hallstatt cemetery

-

Finds from the Hallstatt cemetery

-

Gold and bronze beltplates from Hallstatt

Culture and trade

[edit]

Languages

[edit]It is probable that some if not all of the diffusion of Hallstatt culture took place in a Celtic-speaking context.[17][18][19][20] In northern Italy the Golasecca culture developed with continuity from the Canegrate culture.[21][22] Canegrate represented a completely new cultural dynamic to the area expressed in pottery and bronzework, making it a typical western example of the western Hallstatt culture.[21][22][23]

The Lepontic Celtic language inscriptions of the area show the language of the Golasecca culture was clearly Celtic making it probable that the 13th-century BC precursor language of at least the western Hallstatt was also Celtic or a precursor to it.[21][22] Lepontic inscriptions have also been found in Umbria,[24] in the area which saw the emergence of the Terni culture, which had strong similarities with the Celtic cultures of Hallstatt and La Tène.[25] The Umbrian necropolis of Terni, which dates back to the 10th century BC, was virtually identical in every aspect to the Celtic necropolis of the Golasecca culture.[26]

Older assumptions of the early 20th century of Illyrians having been the bearers of especially the Eastern Hallstatt culture are indefensible and archeologically unsubstantiated.[27][28]

Trade

[edit]Trade with Greece is attested by finds of Attic black-figure pottery in the elite graves of the late Hallstatt period. It was probably imported via Massilia (Marseilles).[29] Other imported luxuries include amber, ivory (as found at the Grafenbühl Tomb) and probably wine. Red kermes dye was imported from the south as well; it was found at Hochdorf. Notable individual imports include the Greek Vix krater (the largest known metal vessel from Western classical antiquity), the Etruscan lebes from Sainte-Colombe-sur-Seine, the Greek hydria from Grächwil, the Greek cauldron from Hochdorf and the Greek or Etruscan cauldron from Lavau.

Settlements

[edit]

The largest settlements were mostly fortified, situated on hilltops, and frequently included the workshops of bronze, silver and gold smiths. Major settlements are known as 'princely seats' (or Fürstensitze in German), and are characterized by elite residences, rich burials, monumental buildings and fortifications. Some of these central sites are described as urban or proto-urban,[30][31][32] and as "the first cities north of the Alps".[33][34] Typical sites of this type are the Heuneburg on the upper Danube surrounded by nine very large grave tumuli, and Mont Lassois in eastern France near Châtillon-sur-Seine with, at its foot, the very rich grave at Vix.[16][35] The Heuneburg is thought to correspond to the Celtic city of 'Pyrene' mentioned by Herodotus in 450 BC.[36][37][38]

Other important sites include the Glauberg, Hohenasperg and Ipf in Germany, the Burgstallkogel in Austria and Molpír in Slovakia. However, most settlements were much smaller villages. The large monumental site of Alte Burg may have had a religious or ceremonial function, and possibly served as a location for games and competitions.[39][40]

At the end of the Hallstatt period many major centres were abandoned and there was a return to a more decentralized settlement pattern. Urban centres later re-emerged across temperate Europe in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC during the La Tène period.[33]

Burial rites

[edit]

The burials at Hallstatt itself show a movement over the period from cremation to inhumation, with grave goods at all times (see above).

In the central Hallstatt regions toward the end of the period (Ha D), very rich graves of high-status individuals under large tumuli are found near the remains of fortified hilltop settlements. Tumuli graves had a chamber, rather large in some cases, lined with timber and with the body and grave goods set about the room. There are some chariot or wagon burials, including Býčí Skála[42] and Brno-Holásky[43] in the Czech Republic, Vix, Sainte-Colombe-sur-Seine and Lavau in France, Hochdorf, Hohmichele and Grafenbühl in Germany, and Mitterkirchen in Austria.[44]

A model of a chariot made from lead has been found in Frög, Carinthia, and clay models of horses with riders are also found. Wooden "funerary carts", presumably used as hearses and then buried, are sometimes found in the grandest graves. Pottery and bronze vessels, weapons, elaborate jewellery made of bronze and gold, as well as a few stone stelae (especially the famous Warrior of Hirschlanden) are found at such burials.[45] The daggers that largely replaced swords in chief's graves in the west were probably not serious weapons, but badges of rank, and used at the table.[10]

Social structure

[edit]

The material culture of Western Hallstatt culture was apparently sufficient to provide a stable social and economic equilibrium. The founding of Marseille and the penetration by Greek and Etruscan culture after c. 600 BC, resulted in long-range trade relationships up the Rhone valley which triggered social and cultural transformations in the Hallstatt settlements north of the Alps. Powerful local chiefdoms emerged which controlled the redistribution of luxury goods from the Mediterranean world that is also characteristic of the La Tène culture.

The apparently largely peaceful and prosperous life of Hallstatt D culture was disrupted, perhaps even collapsed, right at the end of the period. There has been much speculation as to the causes of this, which remain uncertain. Large settlements such as Heuneburg and the Burgstallkogel were destroyed or abandoned, rich tumulus burials ended, and old ones were looted. There was probably a significant movement of population westwards, and the succeeding La Tène culture developed new centres to the west and north, their growth perhaps overlapping with the final years of the Hallstatt culture.[11]

Technology

[edit]Occasional iron artefacts had been appearing in central and western Europe for some centuries before 800 BC (an iron knife or sickle from Ganovce in Slovakia, dating to the 18th century BC, is possibly the earliest evidence of smelted iron in Central Europe).[46] By the later Urnfield (Hallstatt B) phase, some swords were already being made and embellished in iron in eastern Central Europe, and occasionally much further west.[47][46]

Initially iron was rather exotic and expensive, and sometimes used as a prestige material for jewellery.[48] Iron swords became more common after c. 800 BC,[49] and steel was also produced from 800 BC as part of the production of swords.[50] The production of high-carbon steel is attested in Britain after c. 490 BC.[51]

The remarkable uniformity of spoked-wheel wagons from across the Hallstatt region indicates a certain standardisation of production methods, which included techniques such as lathe-turning.[52] Iron tyres were developed and refined in this period, leading to the invention of shrunk-on tyres in the La Tène period.[52] The potter's wheel also appeared in the Hallstatt period.[53]

The extensive use of planking and massive squared beams indicates the use of long saw blades and possibly two-man sawing.[54] The planks of the Hohmichele burial chamber (6th c. BC), which were over 6m long and 35 cm wide, appear to have been sawn by a large timber-yard saw.[55] The construction of monumental buildings such as the Vix palace further demonstrates a "mastery of geometry and carpentry capable of freeing up vast interior spaces."[56]

Analyses of building remains in Silesia have found evidence for the use of a standard unit of length (equivalent to 0.785 m). Remarkably, this is almost identical to the length of a measuring stick found at Borum Eshøj in Denmark (0.7855 m), dating from the Bronze Age (c. 1350 BC).[57] Pythagorean triangles were likely used in building construction to create right angles, and some buildings had ground plans with dimensions corresponding to Pythagorean rectangles.[58]

-

Funerary wagon, reconstruction, Strasbourg Museum, France

-

Wagon wheel hub from the Vix Grave, France

-

Pottery from Heuneburg, Germany

-

Gold bracelets from Sainte-Colombe-sur-Seine, France

-

The Vix krater, imported from Greece

-

Cult wagon from La Côte-Saint-André, France.[60]

-

Hallstatt 'C' swords in Wels Museum, Austria.

-

Dagger with "antenna hilt"

-

Ceramics and sword with gold hilt from Gomadingen

-

Metal vessels from Kleinklein

-

Gold artefacts from the Heuneburg

Art

[edit]

At least the later periods of Hallstatt art from the western zone are generally agreed to form the early period of Celtic art.[62] Decoration is mostly geometric and linear, and best seen on fine metalwork finds from graves (see above). Styles differ, especially between the west and east, with more human figures and some narrative elements in the latter. Animals, with waterfowl a particular favourite, are often included as part of other objects, more often than humans, and in the west there is almost no narrative content such as scenes of combat depicted. These characteristics were continued into the succeeding La Tène style.[63]

Imported luxury art is sometimes found in rich elite graves in the later phases, and certainly had some influence on local styles. The most spectacular objects, such as the Strettweg Cult Wagon,[64] the Warrior of Hirschlanden and the bronze couch supported by "unicyclists" from the Hochdorf Chieftain's Grave are one of a kind in finds from the Hallstatt period, though they can be related to objects from other periods.[65]

More common objects include weapons, in Ha D often with hilts terminating in curving forks ("antenna hilts").[10] Jewellery in metal includes fibulae, often with a row of disks hanging down on chains, armlets and some torcs. This is mostly in bronze, but "princely" burials include items in gold.

The origin of the narrative scenes of the eastern zone, from Hallstatt C onwards, is generally traced to influence from the Situla art of northern Italy and the northern Adriatic, where these bronze buckets began to be decorated in bands with figures in provincial Etruscan centres influenced by Etruscan and Greek art. The fashion for decorated situlae spread north across neighbouring cultures including the eastern Hallstatt zone, beginning around 600 BC and surviving until about 400 BC; the Vače situla is a Slovenian example from near the final period. The style is also found on bronze belt plates, and some of the vocabulary of motifs spread to influence the emerging La Tène style.[66]

According to Ruth and Vincent Megaw, "Situla art depicts life as seen from a masculine viewpoint, in which women are servants or sex objects; most of the scenes which include humans are of the feasts in which the situlae themselves figure, of the hunt or of war".[67] Similar scenes are found on other vessel shapes, as well as bronze belt-plaques.[68] The processions of animals, typical of earlier examples, or humans derive from the Near East and Mediterranean, and Nancy Sandars finds the style shows "a gaucherie that betrays the artist working in a way that is uncongenial, too much at variance with the temper of the craftsmen and the craft". Compared to earlier styles that arose organically in Europe "situla art is weak and sometimes quaint", and "in essence not of Europe".[69]

Except for the Italian Benvenuti Situla, men are hairless, with "funny hats, dumpy bodies and big heads", though often shown looking cheerful in an engaging way. The Benevenuti Situla is also unusual in that it seems to show a specific story.[70]

The Strettweg cult wagon from Austria (c. 600 BC) has been interpreted as representing a deer goddess or 'Great Nature Goddess' similar to Artemis.[71]

Hallstatt culture musical instruments included harps, lyres, zithers, woodwinds, panpipes, horns, drums and rattles.[72][73]

-

Gold collar from Austria, c. 550 BC

-

Gold shoe plaques from Hochdorf

-

Dagger with gold foil added for burial, Hochdorf

-

Replica of the Warrior of Hirschlanden

-

Armband with engraved decoration

-

Bull from Býčí skála Cave, Czech Republic[42]

-

Detail from the Vače situla, Slovenia

-

Wagon model from Frög, Austria

-

Drinking horn from Tuttlingen, Germany

-

Bronze recliner from Hochdorf

-

Pottery from Hegau, Germany

-

Ceramic vessel from Donnerskirchen, Austria

-

Pottery from Hungary, 7th century BC.[74]

-

Bronze fibula brooch, late Hallstatt

Inscriptions

[edit]

A small number of inscriptions have been recovered from Hallstatt culture sites. Markings or symbols inscribed on iron tools from Austria dating from the early Iron Age (Ha C, 800-650 BC) show continuity with symbols from the Bronze Age Urnfield culture, and are thought to be related to mining and the metal trade.[76] Inscriptions engraved on situlas or cauldrons from the Hallstatt cemetery in Austria, dating from c. 800-500 BC, have been interpreted as numerals, letters and words, possibly related to Etruscan or Old Italic scripts.[75][77] Weights from Bavaria dating from the 7th to early 6th century BC bear signs possibly resembling Greek or Etruscan letters.[78] A single-word inscription (possibly a name) on a locally produced ceramic sherd from Montmorot in eastern France, dating from the late 7th to mid-6th century BC, has been identified as either Gaulish or Lepontic, written in either a 'proto-Lepontic' or Etruscan alphabet.[79][80] A fragment of an inscription painted on local pottery has also been recovered from the late Hallstatt site of Bragny-sur-Saône in eastern France, dating from the 5th century BC.[81][82] A letter inscribed on a gold cup was deposited in a princely tomb at Apremont in eastern France, dating from c. 500 BC.[81]

Another fragmentary inscription on pottery was found in a princely burial near Bergères-les-Vertus in north-eastern France, dating from late 5th century BC (at the beginning of La Tène A). The inscription has been identified as the Celtic word for "king", written in the Lepontic alphabet. According to Olivier (2010), "this graffito represents one of the earliest attested occurrences of the word rîx which designates the "king" in the Celtic languages. ... It would also seem to represent the first co-occurrence in the Celtic world of a funerary archaeological context and a contemporaneous linguistic qualification as ‘royal’.”[83] According to Verger (1998) the 7th-6th century BC inscription from Montmorot "is at the beginning of a still limited series of documents attesting to the use of alphabetic signs and the use of writing in Eastern Gaul during the entire period characterised by the appearance, development and end of the Hallstattian 'princely phenomenon'. ... The first transmission of the alphabet north of the Alps, at the end of the 7th or in the first half of the 6th century, seems to be only the beginning of a process that was regularly renewed until the second half of the fifth century."[84]

Calendar

[edit]

The monumental burial mounds at Glauberg and Magdalenenberg in Germany featured structures aligned with the point of the major lunar standstill, which occurs every 18.6 years. At Glauberg this took the form of a 'processional avenue' lined by large ditches,[85] whilst at Magdalenenberg the alignment was marked with a large timber palisade.[86] The knowledge required to create these alignments would have required long-term observation of the skies, possibly over several generations.[85] At Glauberg other ditches and postholes associated with the mound may have been used to observe astronomical phenomena such as the solstices, with the whole ensemble functioning as a calendar.[87][88][89] According to the archaeologist Allard Mees, the numerous burials within the Magdalenenberg mound were positioned to mirror the constellations as they appeared at the time of the summer solstice in 618 BC.[86] Mees argues that the Magdalenenberg represented a lunar calendar and that knowledge of the 18.6 year lunar standstill cycle would have enabled the prediction of lunar eclipses.[90][91] According to Mees many other burial mounds in this period were also aligned with lunar phenomena.[91] An analysis of Hallstatt period burials by Müller-Scheeßel (2005) similarly suggested that they were oriented towards specific constellations.[92] According to Gaspani (1998) the diagonals of the rectangular Hochdorf burial chamber were also aligned with the major lunar standstill.[93][94]

Further evidence for knowledge of lunar eclipse cycles in this period comes from Fiskerton in England, where an analysis of a wooden causeway used to make ritual depositions into the Witham river found that the causeway timbers were felled at intervals corresponding to Saros lunar eclipse cycles, indicating that the builders were able to predict these cycles in advance.[95][96] According to the archaeologists who studied this site, similar evidence can be found at other locations in the British Isles and Central Europe dating from the Late Bronze Age through to the Late Iron Age, suggesting that knowledge of lunar eclipse cycles may have been widespread in this period.[95] Knowledge of Saros cycles may also be numerically encoded on the Late Bronze Age Berlin Gold Hat.[97][98]

The mountain peaks around Hallstatt may have also functioned as a large sundial and visual calendar.[99][100]A similar system is thought to have existed in the Vosges mountains during the Iron Age (the Belchen System) which incorporated dates associated with major Celtic festivals such as Beltane.[101]

Kruta (2010) interprets a large decorated brooch from Hallstatt, dating from the 6th century BC, as representing a 'symbolic summary of the course of the year'. Depictions on the brooch of waterfowl (representing night and winter) and horses (representing day and summer) are placed above a solar boat (representing the sun's journey from one winter solstice to the next), whilst twelve circular pendants represent the lunar months.[102]

According to Garrett Olmsted (2001) the Celtic Coligny calendar, dating from the 1st-2nd centuries AD, has origins dating back to the Hallstatt period or Late Bronze Age, indicating that calendrical knowledge was transmitted through a long oral tradition.[103]

Geography

[edit]

Two culturally distinct areas, an eastern and a western zone are generally recognised.[104] There are distinctions in burial rites, the types of grave goods, and in artistic style. In the western zone, members of the elite were buried with sword (HaC) or dagger (HaD), in the eastern zone with an axe.[62] The western zone has chariot burials. In the eastern zone, warriors are frequently buried with helmet and a plate armour breastplate.[59] Artistic subjects with a narrative component are only found in the east, in both pottery and metalwork.[105] In the east the settlements and cemeteries can be larger than in the west.[62]

The approximate division line between the two subcultures runs from north to south through central Bohemia and Lower Austria at about 14 to 15 degrees eastern longitude, and then traces the eastern and southern rim of the Alps to Eastern and Southern Tyrol.[citation needed]

Western Hallstatt zone

[edit]

Taken at its most generous extent, the western Hallstatt zone includes:

- northeastern France: Burgundy, Franche-Comté, Champagne-Ardenne, Lorraine, Alsace

- northern Switzerland: Swiss plateau

- Southern Germany: much of Swabia and Bavaria

- western Czech Republic: Bohemia

- western Austria: Vorarlberg, Tyrol, Salzkammergut

West Hallstatt influence is also later perceptible in the rest of France, in England and Ireland, in northern Italy and in central, northern and western Iberia.

While Hallstatt is regarded as the dominant settlement of the western zone, a settlement at the Burgstallkogel in the central Sulm valley (southern Styria, west of Leibnitz, Austria) was a major centre during the Hallstatt C period. Parts of the huge necropolis (which originally consisted of more than 1,100 tumuli) surrounding this settlement can be seen today near Gleinstätten, and the chieftain's mounds were on the other side of the hill, near Kleinklein. The finds are mostly in the Landesmuseum Joanneum at Graz, which also holds the Strettweg Cult Wagon.

Eastern Hallstatt zone

[edit]The eastern Hallstatt zone includes:

- eastern Austria: Lower Austria, Upper Styria

- eastern Czech Republic: Moravia

- southwestern Slovakia: Danubian Lowland

- western Hungary: Little Hungarian Plain

- eastern Slovenia: Hallstatt Archaeological Site in Vače (at the border between Lower Styria and Lower Carniola regions), Novo Mesto

- western Slovenia: Svetolucijska Hallstatt culture Most na Soči, Notranjsko kraška Slovene Littoral

- northern Croatia: Hrvatsko Zagorje, Istria

- northern and central Serbia

- parts of southwestern Poland

- northern and western Bulgaria

Trade, cultural diffusion, and some population movements spread the Hallstatt cultural complex (western form) into Britain, and Ireland.

-

Ceramic plate, 8th-7th century BC

-

The Vače Situla, Slovenia

-

Wagon wheel, Vix Grave, France

-

Bronze cauldron, c. 800 BC

-

The Lady of Ditzingen-Schöckingen, Germany

-

Jewellery and headdress, Germany, 6th century BC

-

Etruscan lebes from Sainte-Colombe-sur-Seine

-

Late Hallstatt gold bracelet from Lavau, France

-

Horse equipment from Alfershausen, Germany

-

The Grafenbühl grave, Hohenasperg, Germany

-

Warrior equipment from Slovenia, c.600 BC

-

Belt-plate decorations from Hallstatt

-

Bipyramidal iron bars used as ingots

-

Hallstatt culture artefacts

-

Reconstruction of a house (left) and granary (right) at Burgstallkogel, Austria

-

Hallstatt culture artefacts

-

Gold jewllery from Schöckingen, Germany

-

Bronze ornament, Germany

-

Animal figurine, Austria

-

Pfostenschlizmauer reconstruction, Ipf, Germany

Genetics

[edit]

Damgaard et al. (2018) analyzed the remains of a male and female buried at a Hallstatt cemetery near Litoměřice, Czech Republic between ca. 600 BC and 400 BC. The male carried paternal haplogroup R1b and the maternal haplogroup H6a1a. The female was a carrier of the maternal haplogroup HV0. Damgaard further examined the remains of 5 individuals ascribed to either Hallstatt C or the early La Tène culture. The one male carried Y-haplogroup G2a. The five females carried mt-haplogroups K1a2a, J1c2o, H7d, U5a1a1 and J1c-16261.[106] The examined individuals of the Hallstatt culture and La Tène culture displayed genetic continuity with the earlier Bell Beaker culture, and carried about 50% steppe-related ancestry.[107]

The next study, Fischer et al. (2022), examined 49 genomes from 27 sites in Bronze Age and Iron Age France. The study found of strong genetic continuity between the two periods, particularly in southern France. The samples from northern and southern France were highly homogenous. The northern French samples were distinguished from the southern ones by elevated levels of steppe-related ancestry. R1b was by far the most dominant paternal lineage, while H was the most common maternal lineage. They displayed links to contemporary samples from Great Britain and Sweden. Southern samples displaying links to Celtiberians. The Iron Age samples resembled those of modern-day populations of France, Great Britain and Spain. The evidence suggested that the Celts of the Hallstatt culture largely evolved from local Bronze Age populations.[108]

See also

[edit]- Glauberg

- Hohenasperg

- Ipf (mountain)

- Mont Lassois (commune of Vix)

- Burgstallkogel

- Alte Burg

- Vorstengraf (Oss)

- Grafenbühl grave

- Bronze- and Iron-Age Poland

- Celtic warfare

- Iron Age sword

- Iron Age France

- Iron Age Switzerland

- Noric steel

- Irschen

- Zollfeld

- The Collection of Pre- and Protohistoric Artifacts at the University of Jena

Citations

[edit]- ^ Reinecke, Paul (1902). "Zur Chronologie der 2. Hälfte des Bronzealters in Süd- und Norddeutschland". Korrespondenzbl. D. Deutsch. Ges. F. Anthr., Ethn. U. Urgesch. 33: 17–22. 27–32. ISSN 0931-8046.

- ^ Reinecke, Paul (1965). Mainzer Aufsätze zur Chronologie der Bronze- und Eisenzeit (in German). Bonn: Habelt. OCLC 12201992.

- ^ Eggers, Hans Jürgen (1955). "Zur absoluten Chronologie der römischen Kaiserzeit im Freien Germanien". Jahrbuch des römisch-germanischen Zentralmuseums (in German). 2. Mainz: 192–244. doi:10.11588/jrgzm.1955.0.31095.

- ^ Reinecke, Paul (1922). "Chronologische Übersicht der vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Zeiten". Bayer. Vorgeschichtsfreund. 1–2 (1921–1922): 18–25.

- ^ Tischler, Otto (1881). "Über die Formen der Gewandnadeln (Fibeln) nach ihrer historischen Bedeutung". Zeitschrift für Anthropologie und Urgeschichte Baierns. 4 (1–2): 3–40.

- ^ Friedrich, Michael; Hilke, Hening (1995). "Dendrochronologische Untersuchung der Hölzer des hallstattzeitlichen Wagengrabes 8 aus Wehringen, Lkr. Augsburg und andere Absolutdaten zur Hallstattzeit". Bayerische Vorgeschichtsblätter. 60. München: Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. ISSN 0341-3918.

- ^ McIntosh, 88

- ^ a b Megaw, 26

- ^ Koch

- ^ a b c d Megaw, 40

- ^ a b Megaw, 48–49

- ^ Ehret, D. (2008). "Das Ende des hallstattzeitlichen Bergbaus". In Kern, A.; Kowarik, K.; Rausch, A. W.; Reschreiter, H. (eds.). Salz-Reich. 7000 Jahre Hallstatt (in German). Wien: VPA 2. p. 159. ISBN 978-3-902421-26-5.

- ^ Megaw 25, 29

- ^ Rothe, Klaus (2021). "Digital reconstruction of the Vix palace complex". doi:10.34847/nkl.daden24n.

- ^ Sturhmann, J. (2021). "Digital reconstruction of the Mont Lassois oppidum". doi:10.34847/nkl.67218md8.

- ^ a b Brun, Patrice; Chaume, Bruno; Sacchetti, Federica, eds. (2021). "Vix et le phénomène princier". Ausonius Éditions.

- ^ Chadwick, Nora (1970). The Celts. p. 30.

- ^ Kruta, Venceslas (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. pp. 89–102.

- ^ Stifter, David (2008). Old Celtic Languages - Addenda. p. 25.

- ^ Alfons Semler, Überlingen: Bilder aus der Geschichte einer kleinen Reichsstadt, Oberbadische Verlag, Singen, 1949, pp. 11–17, specifically 15.

- ^ a b c Kruta, Venceslas (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. pp. 93–100.

- ^ a b c Stifter, David (2008). Old Celtic Languages (PDF). p. 24.

- ^ "Celtophile," Ryan Setliff Online. Dec. 24, 2019. https://www.ryansetliff.online/#celtophile

- ^ Percivaldi, Elena (2003). I Celti: una civiltà europea. Giunti Editore. p. 82.

- ^ Leonelli, Valentina. La necropoli delle Acciaierie di Terni: contributi per una edizione critica (Cestres ed.). p. 33.

- ^ Farinacci, Manlio. Carsulae svelata e Terni sotterranea. Associazione Culturale UMRU - Terni.

- ^ Paul Gleirscher: Von wegen Illyrer in Kärnten. Zugleich: von der Beständigkeit lieb gewordener Lehrmeinungen. In: Rudolfinum. Jahrbuch des Landesmuseums für Kärnten. 2006, p. 13–22 (online (PDF) in ZOBODAT).

- ^ "Kein Illyrikum in Norikum – Norisches Kulturmagazin".

- ^ Megaw, 39–41

- ^ Fichtl, Stephan (2018). "Urbanization and oppida". In Haselgrove, Colin; Rebay-Salisbury, Katharina; Wells, Peter (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the European Iron Age. Oxford University Press. pp. 717–740. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199696826.013.13. ISBN 978-0-19-969682-6.

- ^ Fernández-Götz, Manuel; Ralston, Ian (2017). "The Complexity and Fragility of Early Iron Age Urbanism in West-Central Temperate Europe". Journal of World Prehistory. 30 (3): 259–279. doi:10.1007/s10963-017-9108-5. hdl:20.500.11820/72677d8a-b45d-4c7d-85d4-338a9e23299c. S2CID 55839665.

- ^ Zamboni, Lorenzo; Fernández-Götz, Manuel; Metzner-Nebelsick, Carola, eds. (2020). Crossing the Alps: Early Urbanism between Northern Italy and Central Europe (900-400 BC). Sidestone Press. ISBN 9789088909610.

- ^ a b Fernández-Götz, Manuel (2018). "Urbanization in Iron Age Europe: Trajectories, Patterns, and Social Dynamics". Journal of Archaeological Research. 26 (2): 117–162. doi:10.1007/s10814-017-9107-1. hdl:20.500.11820/74e98a7e-45fb-40d5-91c4-727229ba8cc7. S2CID 254594968.

- ^ Krausse, Dirk; Fernández-Götz, Manuel (2012). "Heuneburg: First city north of the Alps". Current World Archaeology. 55: 28–34.

- ^ Megaw, 39–43

- ^ Krause, Dirk (2020). "Earliest town north of the Alps. New excavations and research in the Heuneburg region". In Zamboni, Lorenzo (ed.). Crossing the Alps. Sidestone Press. pp. 299–314. ISBN 978-90-8890-961-0.

Recent excavations indicate that the Heuneburg controlled an area of over 1,000 km² with cemeteries, further hilltop settlements, hamlets, villages, roads and cult or gathering places. It was not only the Heuneburg itself that must have formed an architectonically impressive agglomeration. Consequently, the polis Pyrene stands for this whole system, not just the hillfort of the Heuneburg.

- ^ "Heuneburg - Celtic city of Pyrene". heuneburg-pyrene.de.

- ^ "Herodotus, Histories, Book II: chapters 1‑98". penelope.uchicago.edu.

the Ister [Danube]. That river flows from the land of the Celtae and the city of Pyrene through the very midst of Europe

- ^ Hansen, Leif; Krausse, Dirk; Tarpini, Roberto (2020). "Fortifications of the Early Iron Age in the surroundings of the Princely Seat of Heuneburg". In Delfino, Davide; Coimbra, Fernando; Cardoso, Daniela; Cruz, Gonçalo (eds.). Late Prehistoric Fortifications in Europe: Defensive, Symbolic and Territorial Aspects from the Chalcolithic to the Iron Age. Archaeopress. pp. 113–122.

- ^ Digital reconstruction of the Alte Burg (2021).

- ^ Gretzinger, Joscha; et al. (2024). "Evidence for dynastic succession among early Celtic elites in Central Europe". Nature.

- ^ a b Megaw, 28

- ^ Mírová, Zuzana; Golec, Martin (2018). "Hallstatt Magnate Graves from Brno-Holásky 1 and 2 in the Central European Context". Monograph. Archaeologiae Regionalis Fontes.

- ^ Megaw, 41–43, 45–47

- ^ Megaw, 25-30; 39–47

- ^ a b Hansen, Svend (2019). "The Hillfort of Teleac and Early Iron in Southern Europe". In Hansen, Svend; Krause, Rüdiger (eds.). Bronze Age Fortresses in Europe. Verlag Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn. p. 204.

- ^ Harding, D.W. (2007). The Archaeology of Celtic Art. Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 9781134264643.

- ^ Jope, Martyn (1995). "The social implications of Celtic art: 600 BC to 600 AD". In Green, Miranda (ed.). The Celtic World. Routledge. p. 400. ISBN 9781135632434.

- ^ Sandars, 209

- ^ Wells, Peter (1995). "Resources and Industry". In Green, Miranda (ed.). The Celtic World. Routledge. p. 218. ISBN 9781135632434.

- ^ "East Lothian's Broxmouth fort reveals edge of steel". BBC News. 15 January 2014.

- ^ a b Piggot, Stuart (1995). "Wood and the Wheelwright". In Green, Miranda (ed.). The Celtic World. Routledge. p. 325. ISBN 9781135632434.

- ^ Megaw, 43–44

- ^ Jope, Martyn (1995). "The social implications of Celtic art: 600 BC to 600 AD". In Green, Miranda (ed.). The Celtic World. Routledge. pp. 400–401. ISBN 9781135632434.

- ^ Piggot, Stuart (1995). "Wood and the Wheelwright". In Green, Miranda (ed.). The Celtic World. Routledge. p. 322. ISBN 9781135632434.

- ^ Chaume, Bruno (2011). Vix (Côte-d'Or), une résidence princière au temps de la splendeur d'Athènes. DRAC Bourgogne - Service Régional de l’Archéologie. p. 6.

Au cœur de ce dispositif urbain et au centre de l'enclos le plus vaste, se trouve le grand bâtiment à abside et à antes (prolongements des murs latéraux pour former un porche) du Hallstatt D2-D3, flanqué d'un plus petit. Le premier bâtiment affiche des dimensions exceptionnelles (35m × 22m). L'espace intérieur de 500m3 environ, est divisé en trois pièces d'inégales surfaces. Cette réalisation prouve une maîtrise de la géométrie et du charpentage capable de libérer de vastes espaces intérieurs en construisant un édifice dont las panne faîtière s'établissait à une hauteur de 15m minimum." English translation: "At the heart of this urban arrangement and in the centre of the largest enclosure is the large building with an apse and eaves (extensions of the side walls to form a porch) from Hallstatt D2-D3, flanked by a smaller building. The first building has exceptional dimensions (35 by 22 metres, 115 ft × 72 ft). The interior space of approximately 500 cubic metres (18,000 cu ft) is divided into three rooms of unequal surface area. This achievement demonstrates a mastery of geometry and carpentry capable of freeing up vast interior spaces by constructing a building whose central ceiling ridge was established at a minimum height of 15 metres (49 ft).

- ^ Gralak, Tomasz (2017). Architecture, style and structure in the early iron age in Central Europe. Uniwersytet Wrocławski Instytut Archeologii. doi:10.23734/22.17.001.

- ^ Gralak, Tomasz (2017). Architecture, style and structure in the early iron age in Central Europe. Uniwersytet Wrocławski Instytut Archeologii. doi:10.23734/22.17.001.

- ^ a b Megaw, 34

- ^ "Char de la Côte-Saint-André". lugdunum.grandlyon.com.

- ^ Brattinga, Joris (2012). Two Bridles and a Yoke. A new study into the horse gear from the chieftain's burial of Oss (Masters thesis). Leiden University.

- ^ a b c Megaw, 30

- ^ Megaw, Chapter 1; Laing, chapter 2

- ^ Megaw, 33-34

- ^ Megaw, 39-45

- ^ Megaw, 34-39; Sandars, 223-225

- ^ Megaw, 37

- ^ Sandars, 223-224

- ^ Sandars, 225, quoted

- ^ Sandars, 224

- ^ "Sacred Places and Epichoric Gods in the Southern Alpine Area - Some Aspects". Sacred Places and Epichoric Gods in the Southern Alpine Area - Some Aspects (Marjeta Šašel-Kos, 2000). Études. Ausonius Éditions. 2000. pp. 27–51. ISBN 978-2-35613-260-4.

- ^ Pomberger, Beate Maria (2016). "The Development of Musical Instruments and Sound Objects from the Late Bronze Age to the La Tène Period in the Area between the River Salzach and the Danube Bend".

- ^ Pomberger, Beate Maria (2020). "Stringed instruments of the Hallstatt culture – From iconographic representation to experimental reproduction". Slovenská Archeológia Supplementum 1: 471–482. doi:10.31577/slovarch.2020.suppl.1.40. S2CID 234431894.

- ^ Megaw, 30–32

- ^ a b Sacken, Eduard (1868). Das grabfeld von Hallstatt in Oberösterreich und dessen alterthümer. W. Braumüller, Vienna. pp. 94–95.

- ^ Jahn, Christoph (2013). "5.4 Zeichen im eisenzeitlichen Fundgut". Symbolgut Sichel. Verlag Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn. pp. 224–225. ISBN 978-3-7749-3861-8.

Im Ostalpengebiet begegnet uns in der Urnenfelderzeit auf ausgewählten Objektgruppen ein System von Marken (Abb. 5.6), das sich bis in die ältere und jüngere Eisenzeit verfolgen lässt. […] Die Betrachtung eingeritzter Marken auf eisenzeitlichen Geräten erinnert nicht nur in direkter Weise an die Gussmarken der Knopfund Zungensicheln, sie bleibt im Rahmen der eisenzeitlichen Deponierungen auch dem metallhandwerklichen und montanwirtschaftlichen Kontext der Urnenfelderzeitlichen Niederlegungen verbunden." English translation: "In the Eastern Alpine region, we encounter a system of marks (Fig. 5.6) on selected groups of objects in the Urnfield period, which can be traced into the earlier and later Iron Age. … The observation of engraved marks on Iron Age tools is not only directly reminiscent of the cast marks of the [Urnfield] sickles, it also remains connected to the metal craft and mining economic context of the Urnfield deposits in the context of Iron Age deposits.

- ^ Jahn, Christoph (2013). "5.2 Zeichen im mitteleuropäischen Fundgut". Symbolgut Sichel. Verlag Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn. p. 203. ISBN 978-3-7749-3861-8.

Schon 1868 machte E. v. Sacken auf die negativen Marken auf hallstattzeitlichen Bronzegefäßen und Situlen aufmerksam. Er wies auf die Ähnlichkeit zu etruskischen und altitalienischen Schriftzeichen des norditalienischalpinen Raums hin." English translation: "As early as 1868, E. v. Sacken drew attention to the negative marks on Hallstatt bronze vessels and situlae. He pointed out the similarity to Etruscan and Old Italian characters of the northern Italian Alpine region.

- ^ Pare, Christopher (1999). "Weights and weighing in Bronze Age Central Europe". Eliten in der Bronzezeit. Romisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum. p. 509. ISBN 3-88467-046-8.

Against this background, a pair of Iron Age »weights« from Oberndorf, Bavaria, is especially important [...] The larger piece measured 8.7 × 1.5cm and weighed 35.065g; both sides had a raised sign made up of crosses and curved arcs. The smaller piece measured 5.5 × 1.55cm and weighed 35.1g; one side had a raised sign made up of a zigzag, transverse lines and a curved arc or arcs, the outer edge of the sign was fringed with a row of small impressed dots. The pottery from the grave should be dated to the older or middle Hallstatt period (Ha C1b-D1), i.e. the 7th or early 6th century BC. Although signs resemble Greek or Estruscan letters, they cannot be read easily.

- ^ "JU·1". Lexicon Leponticum.

- ^ Verger, Stéphane (1998). "Note sur un graffite archaïque provenant de l'habitat hallstattien de Montmorot (Jura)". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 142 (3): 619–632.

- ^ a b Verger, Stéphane (1998). "Note sur un graffite archaïque provenant de l'habitat hallstattien de Montmorot (Jura)". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 142 (3): 628.

- ^ Brun, Patrice; Chaume, Bruno (2013). "Une éphémère tentative d'urbanisation en Europe centre-occidentale durant les VIe et Ve siècles av. J.‑C. ?". Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française. 110 (2): 339–340. doi:10.3406/bspf.2013.14263.

- ^ Olivier, Laurent; Markey, Thomas (2010). "Un graffite en caractères lépontiques du Ve siècle av. J.-C. provenant de la nécropole gauloise de Montagnesson à Bergères-les-Vertus (Marne)". Antiquités Nationales. 41.

- ^ Verger, Stéphane (1998). "Note sur un graffite archaïque provenant de l'habitat hallstattien de Montmorot (Jura)". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 142 (3): 628–629.

L'inscription de Montmorot ne peut être considérée comme le témoin d'un épisode isolé et sans lendemain. Elle se place au contraire au début d'une série encore restreinte de documents attestant l'utilisation des signes alphabétiques et l'usage de l'écriture en Gaule de l'Est pendant toute la période caractérisée par l'apparition, le développement et la fin du «phénomène princier» Hallstattien. [...] La première transmission de l'alphabet au nord des Alpes, à la fin du VIIe ou dans la première moitié du VIe siècle, ne semble être en fait que le début d'un processus régulièrement renouvelé jusque dans la seconde moitié du Ve siècle." English translation: "The inscription of Montmorot cannot be considered as the witness of an isolated episode with no future. On the contrary, it is at the beginning of a still limited series of documents attesting to the use of alphabetic signs and the use of writing in Eastern Gaul during the entire period characterised by the appearance, development and end of the Hallstattian 'princely phenomenon'. [...] The first transmission of the alphabet north of the Alps, at the end of the 7th or in the first half of the 6th century, seems to be only the beginning of a process that was regularly renewed until the second half of the fifth century.

- ^ a b Posluschny, Axel; Beusing, Ruth (2019). "Space as the Stage: Understanding the Sacred Landscape Around the Early Celtic Hillfort of the Glauberg". Open Archaeology. 5: 365–382. doi:10.1515/opar-2019-0023.

- ^ a b Mees, Allard (2007). "Der Sternenhimmel vom Magdalenenberg. Das Fürstengrab bei Villingen-Schwenningen – ein Kalenderwerk der Hallstattzeit". Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz. 54 (1): 217–264. doi:10.11588/jrgzm.2007.1.17008.

- ^ Posluschny, Axel (2007). From Landscape Archaeology to Social Archaeology. Finding Patterns to Explain the Development of Early Celtic "Princely Sites" in Middle Europe. In: J. T. Clark/E. Hagemeister (eds.), Digital Discovery. Exploring New Frontiers in Human Heritage. Archaeolingua. pp. 117–127. ISBN 978-9638046901.

it is clear that all these ditches have special astronomic and mathematical meaning, with the great 'Prozessionsstrasse' aiming at the point of the Southern Major Standstill of the moon's 18.61-year precession (maximum extreme of the moon setting), and other ditches aiming at the dates of the solstices. This is evidence for the implications of the whole structure as a ritual or holy place with long term calendrical meaning as well as with short-term seasonal meaning.

- ^ "Princely Seats and Surroundings: The Glauberg". fuerstensitz.de. 2010.

The analyses of Prof. Dr. B. Deiss, Institute for Theoretical Physics/Astrophysics at the University of Frankfurt, prove without a doubt that the ditches of the Glauberg "Procession Way" as well as the ditches and post positions in the area of the "Princely Tomb" together provide clear indications of the use as a calendar, which is only possible in certain geographical situations - such as that of the Glauberg. Specifically, they are aligned with the point of the great southern lunar solstice, which recurs approximately every 18.6 years. The ditches in the northwest of the burial mound and several post positions documented during the excavation form a complex, mathematically well thought-out and constructed system for observing these and other astronomical phenomena, all of which are the basis for a calendar that enables long-term observations to be made for the classification of Time phases, especially of a seasonal nature. (Translated from German)

- ^ "The Glauberg calendar – Glauberg Museum display". wetterau.de.

- ^ "Magdalenenberg: Germany's ancient moon calendar" Current World Archaeology, Nov 2011". 6 November 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ a b Mees, Allard (2017). "Der Magdalenenberg und die Orientierung von keltischen Grabhügeln. Eine bevorzugte Ausrichtung zum Mond?". Neue Forschungenzum Magdalenenberg, Archäologische Informationenaus Baden-Württemberg. Stuttgart, DE.

((cite book)): CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Rebay-Salisbury, Katharina (2016). The Human Body in Early Iron Age Central Europe: Burial Practices and Images of the Hallstatt World. Routledge. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-472-45354-9.

- ^ Rüdel, Reinhardt (2008). "12. Astronomical Orientation of a West Hallstatt Burial Chamber". In Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.). Nuncius Hamburgensis, Volume 8: Prähistorische Astronomie und Ethnoastronomie. pp. 217–221. ISBN 978-3-8370-3131-7.

- ^ Sparavigna, Amelia (2018). "Orione ed il principe celtico di Hochdorf".

- ^ a b Chamberlain, A.T.; Parker Pearson, Mike (2003). "8. The Fiskerton Causeway". In Field, Naomi; Parker Pearson, Mike (eds.). Fiskerton: Iron Age Timber Causeway with Iron Age and Roman Votive Offerings. Oxbow Books. pp. 136–148. JSTOR j.ctv2p7j5qv.15.

- ^ "Altar of the Druids". New Scientist. 2002.

the remains of posts that supported an Iron Age walkway built almost 2500 years ago and used, it would appear, by the Druids of eastern England as a platform from which to consign sacrificial objects to the watery depths. [...] These old oak posts suggest that the people who built the walkway were able to predict lunar eclipses

- ^ Hansen, Rahlf; Rink, Christine (2008). "Himmelsscheibe, Sonnenwagen und Kalenderhüte - ein Versuch zur bronzezeitlichen Astronomie". Acta Praehistorica et Archaeologica. 40: 93–126. doi:10.11588/apa.2008.0.71501.

- ^ "Golden Ceremonial Hat ("Berlin Gold Hat")". Neues Museum Berlin.

Someone who knew how to read these ornaments would be able to calculate the shifts between the solar year and the lunar year, predict lunar eclipses, and set fixed dates for significant events.

- ^ Innerebner, Georg (1953). "Die Bergsonnenuhr von Hallstatt". Jahrbuch des Oberösterreichischen Musealvereines. 98: 177–186.

- ^ Müller, Rolf (1970). Der Himmel über dem Menschen der Steinzeit. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH. p. 143. ISBN 9783540050322.

- ^ Eichin, Walter; Bonhert, Andreas (1988). "Das Belchen-System". Jurablätter. 50 (5): 57–70. doi:10.5169/seals-862554.

- ^ Kruta, Venceslas (2010). "La question de l'art géométrique des Celtes". Ktèma. 35: 243–252. doi:10.3406/ktema.2010.2501.

- ^ Olmsted, Garrett (2001). "A Definitive Reconstructed Text of the Coligny Calendar". Journal of Indo-European Studies.

Plinius's statement implies that the earliest Gaulish calendar originated some 1000 years before the period of the observation he recorded. The earliest of the surviving Gaulish calendrical systems had its origins clearly in the late Bronze Age. This 1000-year span of the 30-year calendar is an inevitable conclusion of Plinius's statement. The 30-year-cycle constant lunar calendar runs ahead of the moon by 1 day every 199 years. Though the months originally began on the first day of the moon, after 1000 years of operation of the calendar the months would have shifted to beginning on the sixth day of the moon. Because of its long evolutionary development with earlier stages still embedded within the later calendar, the Coligny calendar gives a unique window into the astronomical capabilities of a supposedly barbarian people, the Celts of pre-Roman Gaul.

- ^ Koch; Kossack (1959); N. Müller-Scheeßel, Die Hallstattkultur und ihre räumliche Differenzierung. Der West- und Osthallstattkreis aus forschungsgeschichtlicher Sicht (2000)

- ^ Megaw, 30–39

- ^ Brunel et al. 2020, Dataset S1, Rows 215-219.

- ^ Brunel et al. 2020, p. 5.

- ^ Fischer et al. 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Barth, F.E., J. Biel, et al. Vierrädrige Wagen der Hallstattzeit ("The Hallstatt four-wheeled wagons" at Mainz). Mainz: Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum; 1987. ISBN 3-88467-016-6

- Brunel, Samantha; et al. (June 9, 2020). "Ancient genomes from present-day France unveil 7,000 years of its demographic history". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (23). National Academy of Sciences: 12791–12798. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11712791B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1918034117. PMC 7293694. PMID 32457149.

- Damgaard, P. B.; et al. (May 9, 2018). "137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes". Nature. 557 (7705): 369–373. Bibcode:2018Natur.557..369D. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0094-2. hdl:1887/3202709. PMID 29743675. S2CID 13670282. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- Fischer, Claire-Elise; et al. (2022). "Origin and mobility of Iron Age Gaulish groups in present-day France revealed through archaeogenomics". iScience. 25 (4). Cell Press: 104094. Bibcode:2022iSci...25j4094F. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2022.104094. PMC 8983337. PMID 35402880.

- Leskovar, Jutta (2006). "Hallstat [2] the Hallstat culture". In Koch, John T (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-440-7.

- Laing, Lloyd and Jenifer. Art of the Celts, Thames and Hudson, London 1992 ISBN 0-500-20256-7

- McIntosh, Jane, Handbook to Life in Prehistoric Europe, 2009, Oxford University Press (USA), ISBN 9780195384765

- Megaw, Ruth and Vincent, Celtic Art, 2001, Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-28265-X

- Sandars, Nancy K., Prehistoric Art in Europe, Penguin (Pelican, now Yale, History of Art), 1968 (nb 1st edn.)

Further reading

[edit]- Kristinsson, Axel (2010), Expansions: Competition and Conquest in Europe since the Bronze Age, Reykjavík: Reykjavíkur Akademían, ISBN 978-9979-9922-1-9, retrieved 10 October 2011

Documentary

[edit]- Klaus T. Steindl: MYTHOS HALLSTATT - Dawn of the Celts. TV-Documentary featuring new findings and reporting on the state of archeological research on the Celts (2018)[1][2][3]

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Hallstatt culture at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hallstatt culture at Wikimedia Commons

| Bronze Age |

|

|---|---|

| Bronze Age (North Caucasus and Transcaucasia) | |

↓ Iron Age | |

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Other | |

- ^ Hallstatt-forschung (2018-11-08). "STIEGEN-BLOG Archäologische Forschung Hallstatt: Mythos Hallstatt - Eine Dokumentation von Terra Mater". STIEGEN-BLOG Archäologische Forschung Hallstatt. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ Nolf, Markus. "Dokumentarfilm "Terra Mater: Mythos Hallstatt"". www.uibk.ac.at (in German). Archived from the original on 2019-01-15. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ COMPANY. "Mystery of the Celtic Tomb". Terra Mater Factual Studios (in German). Retrieved 2019-01-15.

![Sword hilt inlaid with ivory and amber.[13]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a6/Alice_Schumacher_PA_NHM_Wien_Abb_Salz-Reich_2008_Seite_131_1.jpg/130px-Alice_Schumacher_PA_NHM_Wien_Abb_Salz-Reich_2008_Seite_131_1.jpg)

![Cuirasses and helmet from Kleinklein, Austria, 6th-7th centuries BC.[59]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ab/Hallstatt_culture_Kleinklein_-_muscle_cuirasses_%26_double_ridge_helmet.jpg/130px-Hallstatt_culture_Kleinklein_-_muscle_cuirasses_%26_double_ridge_helmet.jpg)

![Cult wagon from La Côte-Saint-André, France.[60]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d1/Char-gaulois-d-apparat.jpg/130px-Char-gaulois-d-apparat.jpg)

![Burial goods from Oss, Netherlands[61]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/40/Vorstengraf_Oss_-_bronzen_situla_met_inhoud_en_zwaard_-_700_v_Chr_-_RMO.png/130px-Vorstengraf_Oss_-_bronzen_situla_met_inhoud_en_zwaard_-_700_v_Chr_-_RMO.png)

![Bull from Býčí skála Cave, Czech Republic[42]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9d/NHM_-_Byci_Skala_Stier.jpg/130px-NHM_-_Byci_Skala_Stier.jpg)