Hildegard of Bingen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Virgin, Doctor of the Church | |

| Born | Hildegard von Bingen c. 1098 Bermersheim vor der Höhe, County Palatine of the Rhine, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 17 September 1179 (aged 81) Bingen am Rhein, County Palatine of the Rhine, Holy Roman Empire |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church, Anglican Communion, Lutheranism |

| Beatified | 26 August 1326 (Formal confirmation of Cultus) by Pope John XXII |

| Canonized | 10 May 2012 (equivalent canonization), Vatican City by Pope Benedict XVI |

| Major shrine | Eibingen Abbey, Germany |

| Feast | 17 September |

Philosophy career | |

| Notable work | |

| Era | Medieval philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Neoplatonism |

Main interests | mystical theology, medicine, botany, natural history, music, literature |

Notable ideas | Microcosm–macrocosm analogy, Eternal predestination of Christ, viriditas, Lingua ignota, humoral theory, morality play |

| Part of a series on |

| Christian mysticism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Medieval music |

|---|

| Overview |

|

|

Hildegard of Bingen (German: Hildegard von Bingen, pronounced [ˈhɪldəɡaʁt fɔn ˈbɪŋən]; Latin: Hildegardis Bingensis; c. 1098 – 17 September 1179), also known as Saint Hildegard and the Sibyl of the Rhine, was a German Benedictine abbess and polymath active as a writer, composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary, and as a medical writer and practitioner during the High Middle Ages.[1][2] She is one of the best-known composers of sacred monophony, as well as the most recorded in modern history.[3] She has been considered by a number of scholars to be the founder of scientific natural history in Germany.[4]

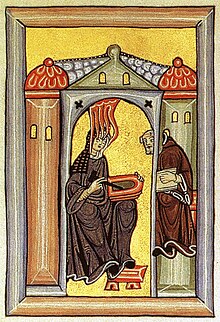

Hildegard's convent at Disibodenberg elected her as magistra (mother superior) in 1136. She founded the monasteries of Rupertsberg in 1150 and Eibingen in 1165. Hildegard wrote theological, botanical, and medicinal works,[5] as well as letters, hymns, and antiphons for the liturgy.[2] She wrote poems, and supervised miniature illuminations in the Rupertsberg manuscript of her first work, Scivias.[6] There are more surviving chants by Hildegard than by any other composer from the entire Middle Ages, and she is one of the few known composers to have written both the music and the words.[7] One of her works, the Ordo Virtutum, is an early example of liturgical drama and arguably the oldest surviving morality play.[a] She is noted for the invention of a constructed language known as Lingua Ignota.

Although the history of her formal canonization is complicated, regional calendars of the Roman Catholic Church have listed her as a saint for centuries. On 10 May 2012, Pope Benedict XVI extended the liturgical cult of Hildegard to the entire Catholic Church in a process known as "equivalent canonization". On 7 October 2012, he named her a Doctor of the Church, in recognition of "her holiness of life and the originality of her teaching."[8]

Hildegard was born around 1098. Her parents were Mechtild of Merxheim-Nahet and Hildebert of Bermersheim, a family of the free lower nobility in the service of the Count Meginhard of Sponheim.[9] Sickly from birth, Hildegard is traditionally considered their youngest and tenth child,[10] although there are records of only seven older siblings.[11][12] In her Vita, Hildegard states that from a very young age she experienced visions.[13]

From early childhood, long before she undertook her public mission or even her monastic vows, Hildegard's spiritual awareness was grounded in what she called the umbra viventis lucis, the reflection of the living Light. Her letter to Guibert of Gembloux, which she wrote at the age of 77, describes her experience of this light:

From my early childhood, before my bones, nerves, and veins were fully strengthened, I have always seen this vision in my soul, even to the present time when I am more than seventy years old. In this vision, my soul, as God would have it, rises up high into the vault of heaven and into the changing sky and spreads itself out among different peoples, although they are far away from me in distant lands and places. And because I see them this way in my soul, I observe them in accord with the shifting of clouds and other created things. I do not hear them with my outward ears, nor do I perceive them by the thoughts of my own heart or by any combination of my five senses, but in my soul alone, while my outward eyes are open. So I have never fallen prey to ecstasy in the visions, but I see them wide awake, day and night. And I am constantly fettered by sickness, and often in the grip of pain so intense that it threatens to kill me, but God has sustained me until now. The light which I see thus is not spatial, but it is far, far brighter than a cloud which carries the sun. I can measure neither height, nor length, nor breadth in it; and I call it "the reflection of the living Light." And as the sun, the moon, and the stars appear in water, so writings, sermons, virtues, and certain human actions take form for me and gleam.[14]

Perhaps because of Hildegard's visions or as a method of political positioning, or both, Hildegard's parents offered her as an oblate to the Benedictine monastery at Disibodenberg, which had been recently reformed in the Palatinate Forest. The date of Hildegard's enclosure at the monastery is the subject of debate. Her Vita says she was eight years old when she was professed with Jutta, who was the daughter of Count Stephan II of Sponheim and about six years older than Hildegard.[15] However, Jutta's date of enclosure is known to have been in 1112, when Hildegard would have been 14.[16] Their vows were received by Bishop Otto of Bamberg on All Saints Day 1112. Some scholars speculate that Hildegard was placed in the care of Jutta at the age of eight, and that the two of them were then enclosed together six years later.[17]

In any case, Hildegard and Jutta were enclosed together at Disibodenberg and formed the core of a growing community of women attached to the monastery of monks, named a Frauenklause, a type of female hermitage. Jutta was also a visionary and thus attracted many followers who came to visit her at the monastery. Hildegard states that Jutta taught her to read and write, but that she was unlearned, and therefore incapable of teaching Hildegard sound Biblical interpretation.[18] The written record of the Life of Jutta indicates that Hildegard probably assisted her in reciting the psalms, working in the garden, other handiwork, and tending to the sick.[19] This might have been a time when Hildegard learned how to play the ten-stringed psaltery. Volmar, a frequent visitor, may have taught Hildegard simple psalm notation. The time she studied music could have been the beginning of the compositions she would later create.[20]

Upon Jutta's death in 1136, Hildegard was unanimously elected as magistra of the community by her fellow nuns.[21] Abbot Kuno of Disibodenberg asked Hildegard to be Prioress, which would be under his authority. Hildegard, however, wanted more independence for herself and her nuns and asked Abbot Kuno to allow them to move to Rupertsberg.[22] This was to be a move toward poverty, from a stone complex that was well established to a temporary dwelling place. When the abbot declined Hildegard's proposition, Hildegard went over his head and received the approval of Archbishop Henry I of Mainz. Abbot Kuno did not relent, however, until Hildegard was stricken by an illness that rendered her paralyzed and unable to move from her bed, an event that she attributed to God's unhappiness at her not following his orders to move her nuns to Rupertsberg. It was only when the Abbot himself could not move Hildegard that he decided to grant the nuns their own monastery.[23] Hildegard and approximately 20 nuns thus moved to the St. Rupertsberg monastery in 1150, where Volmar served as provost, as well as Hildegard's confessor and scribe. In 1165, Hildegard founded a second monastery for her nuns at Eibingen.[24]

Before Hildegard's death in 1179, a problem arose with the clergy of Mainz: a man buried in Rupertsberg had died after excommunication from the Catholic Church. Therefore, the clergy wanted to remove his body from the sacred ground. Hildegard did not accept this idea, replying that it was a sin and that the man had been reconciled to the church at the time of his death.[25]

Hildegard said that she first saw "The Shade of the Living Light" at the age of three, and by the age of five, she began to understand that she was experiencing visions.[26] She used the term visio (Latin for 'vision') to describe this feature of her experience and she recognized that it was a gift that she could not explain to others. Hildegard explained that she saw all things in the light of God through the five senses: sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch.[27] Hildegard was hesitant to share her visions, confiding only to Jutta, who in turn told Volmar, Hildegard's tutor and, later, secretary.[28] Throughout her life, she continued to have many visions, and in 1141, at the age of 42, Hildegard received a vision she believed to be an instruction from God, to "write down that which you see and hear."[29] Still hesitant to record her visions, Hildegard became physically ill. The illustrations recorded in the book of Scivias were visions that Hildegard experienced, causing her great suffering and tribulations.[30] In her first theological text, Scivias ("Know the Ways"), Hildegard describes her struggle within:

But I, though I saw and heard these things, refused to write for a long time through doubt and bad opinion and the diversity of human words, not with stubbornness but in the exercise of humility, until, laid low by the scourge of God, I fell upon a bed of sickness; then, compelled at last by many illnesses, and by the witness of a certain noble maiden of good conduct [the nun Richardis von Stade] and of that man whom I had secretly sought and found, as mentioned above, I set my hand to the writing. While I was doing it, I sensed, as I mentioned before, the deep profundity of scriptural exposition; and, raising myself from illness by the strength I received, I brought this work to a close – though just barely – in ten years. [...] And I spoke and wrote these things not by the invention of my heart or that of any other person, but as by the secret mysteries of God I heard and received them in the heavenly places. And again I heard a voice from Heaven saying to me, 'Cry out, therefore, and write thus!'

— Hildegard von Bingen, Scivias, translated by Columba Hart and Jane Bishop, 1990[31]

It was between November 1147 and February 1148 at the synod in Trier that Pope Eugenius heard about Hildegard's writings. It was from this that she received Papal approval to document her visions as revelations from the Holy Spirit, giving her instant credence.[32]

On 17 September 1179, when Hildegard died, her sisters claimed they saw two streams of light appear in the skies and cross over the room where she was dying.[33]

Hildegard's hagiography, Vita Sanctae Hildegardis, was compiled by the monk Theoderic of Echternach after Hildegard's death.[34] He included the hagiographical work Libellus, or "Little Book", begun by Godfrey of Disibodenberg.[35] Godfrey had died before he was able to complete his work. Guibert of Gembloux was invited to finish the work; however, he had to return to his monastery with the project unfinished.[36] Theoderic utilized sources Guibert had left behind to complete the Vita.

Hildegard's works include three great volumes of visionary theology;[38] a variety of musical compositions for use in the liturgy, as well as the musical morality play Ordo Virtutum; one of the largest bodies of letters (nearly 400) to survive from the Middle Ages, addressed to correspondents ranging from popes to emperors to abbots and abbesses, and including records of many of the sermons she preached in the 1160s and 1170s;[39] two volumes of material on natural medicine and cures;[40][41] an invented language called the Lingua Ignota ('unknown language');[42] and various minor works, including a gospel commentary and two works of hagiography.[43]

Several manuscripts of her works were produced during her lifetime, including the illustrated Rupertsberg manuscript of her first major work, Scivias; the Dendermonde Codex, which contains one version of her musical works; and the Ghent manuscript, which was the first fair-copy made for editing of her final theological work, the Liber Divinorum Operum. At the end of her life, and probably under her initial guidance, all of her works were edited and gathered into the single Riesenkodex manuscript.[44][45] The Riesenkodex manuscript is a collection of 481 folios of vellum bounded by wooden boards bound in pig leather that measure 45 by 30 centimetres (18 by 12 in).[46]

Hildegard's most significant works were her three volumes of visionary theology: Scivias ("Know the Ways", composed 1142–1151), Liber Vitae Meritorum ("Book of Life's Merits" or "Book of the Rewards of Life", composed 1158–1163); and Liber Divinorum Operum ("Book of Divine Works", also known as De operatione Dei, "On God's Activity", begun around 1163 or 1164 and completed around 1172 or 1174). In these volumes, the last of which was completed when she was well into her seventies, Hildegard first describes each vision, whose details are often strange and enigmatic, and then interprets their theological contents in the words of the "voice of the Living Light."[47]

With permission from Abbot Kuno of Disibodenberg, she began journaling visions she had (which is the basis for Scivias). Scivias is a contraction of Sci vias Domini ('Know the Ways of the Lord'), and it was Hildegard's first major visionary work, and one of the biggest milestones in her life. Perceiving a divine command to "write down what you see and hear,"[48] Hildegard began to record and interpret her visionary experiences. In total, 26 visionary experiences were captured in this compilation.[32]

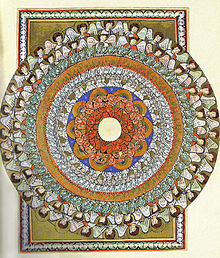

Scivias is structured into three parts of unequal length. The first part (six visions) chronicles the order of God's creation: the Creation and Fall of Adam and Eve, the structure of the universe (described as the shape of an "egg"), the relationship between body and soul, God's relationship to his people through the Synagogue, and the choirs of angels. The second part (seven visions) describes the order of redemption: the coming of Christ the Redeemer, the Trinity, the church as the Bride of Christ and the Mother of the Faithful in baptism and confirmation, the orders of the church, Christ's sacrifice on the cross and the Eucharist, and the fight against the devil. Finally, the third part (thirteen visions) recapitulates the history of salvation told in the first two parts, symbolized as a building adorned with various allegorical figures and virtues. It concludes with the Symphony of Heaven, an early version of Hildegard's musical compositions.[49]

In early 1148, a commission was sent by the Pope to Disibodenberg to find out more about Hildegard and her writings. The commission found that the visions were authentic and returned to the Pope, with a portion of the Scivias. Portions of the uncompleted work were read aloud to Pope Eugenius III at the Synod of Trier in 1148, after which he sent Hildegard a letter with his blessing.[50] This blessing was later construed as papal approval for all of Hildegard's wide-ranging theological activities.[51] Towards the end of her life, Hildegard commissioned a richly decorated manuscript of Scivias (the Rupertsberg Codex); although the original has been lost since its evacuation to Dresden for safekeeping in 1945, its images are preserved in a hand-painted facsimile from the 1920s.[6]

In her second volume of visionary theology, Liber Vitae Meritorum, composed between 1158 and 1163, after she had moved her community of nuns into independence at the Rupertsberg in Bingen, Hildegard tackled the moral life in the form of dramatic confrontations between the virtues and the vices. She had already explored this area in her musical morality play, Ordo Virtutum, and the "Book of the Rewards of Life" takes up the play's characteristic themes. Each vice, although ultimately depicted as ugly and grotesque, nevertheless offers alluring, seductive speeches that attempt to entice the unwary soul into their clutches. Standing in humankind's defence, however, are the sober voices of the Virtues, powerfully confronting every vicious deception.[52]

Amongst the work's innovations is one of the earliest descriptions of purgatory as the place where each soul would have to work off its debts after death before entering heaven.[53] Hildegard's descriptions of the possible punishments there are often gruesome and grotesque, which emphasize the work's moral and pastoral purpose as a practical guide to the life of true penance and proper virtue.[54]

Hildegard's last and grandest visionary work, Liber divinorum operum, had its genesis in one of the few times she experienced something like an ecstatic loss of consciousness. As she described it in an autobiographical passage included in her Vita, sometime in about 1163, she received "an extraordinary mystical vision" in which was revealed the "sprinkling drops of sweet rain" that she stated John the Evangelist experienced when he wrote, "In the beginning was the Word" (John 1:1).[b] Hildegard perceived that this Word was the key to the "Work of God", of which humankind is the pinnacle. The Book of Divine Works, therefore, became in many ways an extended explication of the prologue to the Gospel of John.[56]

The ten visions of this work's three parts are cosmic in scale, to illustrate various ways of understanding the relationship between God and his creation. Often, that relationship is established by grand allegorical female figures representing Divine Love (Caritas) or Wisdom (Sapientia). The first vision opens the work with a salvo of poetic and visionary images, swirling about to characterize God's dynamic activity within the scope of his work within the history of salvation. The remaining three visions of the first part introduce the image of a human being standing astride the spheres that make up the universe and detail the intricate relationships between the human as microcosm and the universe as macrocosm. This culminates in the final chapter of Part One, Vision Four with Hildegard's commentary on the prologue to the Gospel of John (John 1:1–14), a direct rumination on the meaning of "In the beginning was the Word". The single vision that constitutes the whole of Part Two stretches that rumination back to the opening of Genesis, and forms an extended commentary on the seven days of the creation of the world told in Genesis 1–2:3. This commentary interprets each day of creation in three ways: literal or cosmological; allegorical or ecclesiological (i.e. related to the church's history); and moral or tropological (i.e. related to the soul's growth in virtue). Finally, the five visions of the third part take up again the building imagery of Scivias to describe the course of salvation history. The final vision (3.5) contains Hildegard's longest and most detailed prophetic program of the life of the church from her own days of "womanish weakness" through to the coming and ultimate downfall of the Antichrist.[57]

Attention in recent decades to women of the medieval Catholic Church has led to a great deal of popular interest in Hildegard's music. In addition to the Ordo Virtutum, 69 musical compositions, each with its own original poetic text, survive, and at least four other texts are known, though their musical notation has been lost.[58] This is one of the largest repertoires among medieval composers.

One of her better-known works, Ordo Virtutum (Play of the Virtues), is a morality play. It is uncertain when some of Hildegard's compositions were composed, though the Ordo Virtutum is thought to have been composed as early as 1151.[59] It is an independent Latin morality play with music (82 songs); it does not supplement or pay homage to the Mass or the Office of a certain feast. It is, in fact, the earliest known surviving musical drama that is not attached to a liturgy.[7]

The Ordo virtutum would have been performed within Hildegard's monastery by and for her select community of noblewomen and nuns. It was probably performed as a manifestation of the theology Hildegard delineated in the Scivias. The play serves as an allegory of the Christian story of sin, confession, repentance, and forgiveness. Notably, it is the female Virtues who restore the fallen to the community of the faithful, not the male Patriarchs or Prophets. This would have been a significant message to the nuns in Hildegard's convent. Scholars assert that the role of the Devil would have been played by Volmar, while Hildegard's nuns would have played the parts of Anima (the human souls) and the Virtues.[60] The devil's part is entirely spoken or shouted, with no musical setting. All other characters sing in monophonic plainchant. This includes patriarchs, prophets, a happy soul, an unhappy soul, and a penitent soul along with 16 virtues (including mercy, innocence, chastity, obedience, hope, and faith).[61]

In addition to the Ordo Virtutum, Hildegard composed many liturgical songs that were collected into a cycle called the Symphonia armoniae celestium revelationum. The songs from the Symphonia are set to Hildegard's own text and range from antiphons, hymns, and sequences (such as Columba Aspexit), to responsories.[62] Her music is monophonic, consisting of exactly one melodic line.[63] Its style has been said to be characterized by soaring melodies that can push the boundaries of traditional Gregorian chant and to stand outside the normal practices of monophonic monastic chant.[64] Researchers are also exploring ways in which it may be viewed in comparison with her contemporaries, such as Hermannus Contractus.[65] Another feature of Hildegard's music that both reflects the 12th-century evolution of chant, and pushes that evolution further, is that it is highly melismatic, often with recurrent melodic units. Scholars such as Margot Fassler, Marianne Richert Pfau, and Beverly Lomer also note the intimate relationship between music and text in Hildegard's compositions, whose rhetorical features are often more distinct than is common in 12th-century chant.[66] As with most medieval chant notation, Hildegard's music lacks any indication of tempo or rhythm; the surviving manuscripts employ late German style notation, which uses very ornamental neumes.[67] The reverence for the Virgin Mary reflected in music shows how deeply influenced and inspired Hildegard of Bingen and her community were by the Virgin Mary and the saints.[68]

Hildegard's medicinal and scientific writings, although thematically complementary to her ideas about nature expressed in her visionary works, are different in focus and scope. Neither claim to be rooted in her visionary experience and its divine authority. Rather, they spring from her experience helping in and then leading the monastery's herbal garden and infirmary, as well as the theoretical information she likely gained through her wide-ranging reading in the monastery's library.[41] As she gained practical skills in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment, she combined physical treatment of physical diseases with holistic methods centered on "spiritual healing".[69] She became well known for her healing powers involving the practical application of tinctures, herbs, and precious stones.[70] She combined these elements with a theological notion ultimately derived from Genesis: all things put on earth are for the use of humans.[71] In addition to her hands-on experience, she also gained medical knowledge, including elements of her humoral theory, from traditional Latin texts.[69]

Hildegard catalogued both her theory and practice in two works. The first, Physica, contains nine books that describe the scientific and medicinal properties of various plants, stones, fish, reptiles, and animals. This document is also thought to contain the first recorded reference of the use of hops in beer as a preservative.[72][73] The second, Causae et Curae, is an exploration of the human body, its connections to the rest of the natural world, and the causes and cures of various diseases.[74] Hildegard documented various medical practices in these books, including the use of bleeding and home remedies for many common ailments. She also explains remedies for common agricultural injuries such as burns, fractures, dislocations, and cuts.[69] Hildegard may have used the books to teach assistants at the monastery. These books are historically significant because they show areas of medieval medicine that were not well documented because their practitioners, mainly women, rarely wrote in Latin. Her writings were commentated on by Mélanie Lipinska, a Polish scientist.[75]

In addition to its wealth of practical evidence, Causae et Curae is also noteworthy for its organizational scheme. Its first part sets the work within the context of the creation of the cosmos and then humanity as its summit, and the constant interplay of the human person as microcosm both physically and spiritually with the macrocosm of the universe informs all of Hildegard's approach.[41] Her hallmark is to emphasize the vital connection between the "green" health of the natural world and the holistic health of the human person. Viriditas, or greening power, was thought to sustain human beings and could be manipulated by adjusting the balance of elements within a person.[69] Thus, when she approached medicine as a type of gardening, it was not just as an analogy. Rather, Hildegard understood the plants and elements of the garden as direct counterparts to the humors and elements within the human body, whose imbalance led to illness and disease.[69]

The nearly three hundred chapters of the second book of Causae et Curae "explore the etiology, or causes, of disease as well as human sexuality, psychology, and physiology."[41] In this section, she gives specific instructions for bleeding based on various factors, including gender, the phase of the moon (bleeding is best done when the moon is waning), the place of disease (use veins near diseased organ or body part) or prevention (big veins in arms), and how much blood to take (described in imprecise measurements, like "the amount that a thirsty person can swallow in one gulp"). She even includes bleeding instructions for animals to keep them healthy. In the third and fourth sections, Hildegard describes treatments for malignant and minor problems and diseases according to the humoral theory, again including information on animal health. The fifth section is about diagnosis and prognosis, which includes instructions to check the patient's blood, pulse, urine, and stool.[69] Finally, the sixth section documents a lunar horoscope to provide an additional means of prognosis for both disease and other medical conditions, such as conception and the outcome of pregnancy.[41] For example, she indicates that a waxing moon is good for human conception and is also good for sowing seeds for plants (sowing seeds is the plant equivalent of conception).[69] Elsewhere, Hildegard is even said to have stressed the value of boiling drinking water in an attempt to prevent infection.[76]

As Hildegard elaborates the medical and scientific relationship between the human microcosm and the macrocosm of the universe, she often focuses on interrelated patterns of four: "the four elements (fire, air, water, and earth), the four seasons, the four humors, the four zones of the earth, and the four major winds."[41] Although she inherited the basic framework of humoral theory from ancient medicine, Hildegard's conception of the hierarchical inter-balance of the four humors (blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile) was unique, based on their correspondence to "superior" and "inferior" elements – blood and phlegm corresponding to the "celestial" elements of fire and air, and the two biles corresponding to the "terrestrial" elements of water and earth. Hildegard understood the disease-causing imbalance of these humors to result from the improper dominance of the subordinate humors. This disharmony reflects that introduced by Adam and Eve in the Fall, which for Hildegard marked the indelible entrance of disease and humoral imbalance into humankind.[41] As she writes in Causae et Curae c. 42:

It happens that certain men suffer diverse illnesses. This comes from the phlegm which is superabundant within them. For if man had remained in paradise, he would not have had the flegmata within his body, from which many evils proceed, but his flesh would have been whole and without dark humor [livor]. However, because he consented to evil and relinquished good, he was made into a likeness of the earth, which produces good and useful herbs, as well as bad and useless ones, and which has in itself both good and evil moistures. From tasting evil, the blood of the sons of Adam was turned into the poison of semen, out of which the sons of man are begotten. And therefore their flesh is ulcerated and permeable [to disease]. These sores and openings create a certain storm and smoky moisture in men, from which the flegmata arise and coagulate, which then introduce diverse infirmities to the human body. All this arose from the first evil, which man began at the start, because if Adam had remained in paradise, he would have had the sweetest health, and the best dwelling-place, just as the strongest balsam emits the best odor; but on the contrary, man now has within himself poison and phlegm and diverse illnesses.[77]

Hildegard also invented an alternative alphabet. Litterae ignotae ('Alternate Alphabet') was another work and was more or less a secret code, or even an intellectual code – much like a modern crossword puzzle today.

Hildegard's Lingua ignota ('unknown language') consisted of a series of invented words that corresponded to an eclectic list of nouns. The list is approximately 1,000 nouns; there are no other parts of speech.[78] The two most important sources for the Lingua ignota are the Wiesbaden, Hessische Landesbibliothek 2 (nicknamed the Riesenkodex)[78] and the Berlin manuscript.[42] In both manuscripts, medieval German and Latin glosses are written above Hildegard's invented words. The Berlin manuscript contains additional Latin and German glosses not found in the Riesenkodex.[42] The first two words of the Lingua as copied in the Berlin manuscript are aigonz (German, goth; Latin, deus; English, god) and aleganz (German, engel; Latin, angelus; English, angel).[79]

Barbara Newman believes that Hildegard used her Lingua ignota to increase solidarity among her nuns.[80] Sarah Higley disagrees and notes that there is no evidence of Hildegard teaching the language to her nuns. She suggests that the language was not intended to remain a secret; rather, the presence of words for mundane things may indicate that the language was for the whole abbey and perhaps the larger monastic world.[42] Higley believes that "the Lingua is a linguistic distillation of the philosophy expressed in her three prophetic books: it represents the cosmos of divine and human creation and the sins that flesh is heir to."[42]

The text of her writing and compositions reveals Hildegard's use of this form of modified medieval Latin, encompassing many invented, conflated, and abridged words.[13] Because of her inventions of words for her lyrics and use of a constructed script, many conlangers look upon her as a medieval precursor.[81]

Maddocks claims that it is likely Hildegard learned simple Latin and the tenets of the Christian faith, but was not instructed in the Seven Liberal Arts, which formed the basis of all education for the learned classes in the Middle Ages: the Trivium of grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric plus the Quadrivium of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music.[82] The correspondence she kept with the outside world, both spiritual and social, transcended the cloister as a space of spiritual confinement and served to document Hildegard's grand style and strict formatting of medieval letter writing.[83][84]

Contributing to Christian European rhetorical traditions, Hildegard "authorized herself as a theologian" through alternative rhetorical arts.[83] Hildegard was creative in her interpretation of theology. She believed that her monastery should exclude novices who were not from the nobility because she did not want her community to be divided on the basis of social status.[85] She also stated that "woman may be made from man, but no man can be made without a woman."[33]

Because of church limitation on public, discursive rhetoric, the medieval rhetorical arts included preaching, letter writing, poetry, and the encyclopedic tradition.[86] Hildegard's participation in these arts speaks to her significance as a female rhetorician, transcending bans on women's social participation and interpretation of scripture. The acceptance of public preaching by a woman, even a well-connected abbess and acknowledged prophet, does not fit the stereotype of this time. Her preaching was not limited to the monasteries; she preached publicly in 1160 in Germany.[87] She conducted four preaching tours throughout Germany, speaking to both clergy and laity in chapter houses and in public, mainly denouncing clerical corruption and calling for reform.[88]

Many abbots and abbesses asked her for prayers and opinions on various matters.[1] She traveled widely during her four preaching tours.[89] She had several devoted followers, including Guibert of Gembloux, who wrote to her frequently and became her secretary after Volmar's death in 1173. Hildegard also influenced several monastic women, exchanging letters with Elisabeth of Schönau, a nearby visionary.[90]

Hildegard corresponded with popes such as Eugene III and Anastasius IV, statesmen such as Abbot Suger, German emperors such as Frederick I Barbarossa, and other notable figures such as Bernard of Clairvaux, who advanced her work, at the behest of her abbot, Kuno, at the Synod of Trier in 1147 and 1148. Hildegard of Bingen's correspondence is an important component of her literary output.[91]

Hildegard was one of the first persons for whom the Roman canonization process was officially applied, but the process took so long that four attempts at canonization were not completed and she remained at the level of her beatification. Her name was nonetheless included in the Roman Martyrology at the end of the 16th century up to the current 2004 edition, listing her as "Saint Hildegard" with her feast on 17 September, which would eventually be added to the General Roman Calendar as an optional memorial.[92] Numerous popes have referred to Hildegard as a saint, including Pope John Paul II[93] and Pope Benedict XVI.[94] Hildegard's parish and pilgrimage church in Eibingen near Rüdesheim houses her relics.[95]

On 10 May 2012, Pope Benedict XVI extended the veneration of Saint Hildegard to the entire Catholic Church[96] in a process known as "equivalent canonization,"[97] thus laying the groundwork for naming her a Doctor of the Church.[98] On 7 October 2012, the feast of the Holy Rosary, the pope named her a Doctor of the Church.[99] He called Hildegard "perennially relevant" and "an authentic teacher of theology and a profound scholar of natural science and music."[100]

Hildegard of Bingen also appears in the calendar of saints of various Anglican churches, such as that of the Church of England, in which she is commemorated on 17 September.[101][102]

In recent years, Hildegard has become of particular interest to feminist scholars.[103] They note her reference to herself as a member of the weaker sex and her rather constant belittling of women. Hildegard frequently referred to herself as an unlearned woman, completely incapable of Biblical exegesis.[104] Such a statement on her part, however, worked slyly to her advantage because it made her statements that all of her writings and music came from visions of the Divine more believable, therefore giving Hildegard the authority to speak in a time and place where few women were permitted a voice.[105] Hildegard used her voice to amplify the church's condemnation of institutional corruption, in particular simony.

Hildegard has also become a figure of reverence within the contemporary New Age movement, mostly because of her holistic and natural view of healing, as well as her status as a mystic. Although her medical writings were long neglected and then, studied without reference to their context,[106] she was the inspiration for Dr. Gottfried Hertzka's "Hildegard-Medicine", and is the namesake for June Boyce-Tillman's Hildegard Network, a healing center that focuses on a holistic approach to wellness and brings together people interested in exploring the links between spirituality, the arts, and healing.[107] Her reputation as a medicinal writer and healer was also used by early feminists to argue for women's rights to attend medical schools.[106]

Reincarnation of Hildegard has been debated since 1924 when Austrian mystic Rudolf Steiner lectured that a nun of her description was the past life of Russian poet-philosopher Vladimir Soloviev,[108] whose visions of Holy Wisdom are often compared to Hildegard's.[109] Sophiologist Robert Powell writes that hermetic astrology proves the match,[110] while mystical communities in Hildegard's lineage include that of artist Carl Schroeder[111] as studied by Columbia sociologist Courtney Bender[112] and supported by reincarnation researchers Walter Semkiw and Kevin Ryerson.[113]

Recordings and performances of Hildegard's music have gained critical praise and popularity since 1979. There is an extensive discography of her musical works.

The following modern musical works are directly linked to Hildegard and her music or texts:

The artwork The Dinner Party features a place setting for Hildegard.[121]

In space, the minor planet 898 Hildegard is named for her.[122]

Hildegard was the subject of a 2012 fictionalized biographic novel Illuminations by Mary Sharatt.[123]

The plant genus Hildegardia is named after her because of her contributions to herbal medicine.[124]

The off-Broadway musical In the Green, written by Grace McLean, followed Hildegard's story.[125]

In his book, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, neurologist Oliver Sacks devotes a chapter to Hildegard and concludes that in his opinion her visions were migrainous.[126]

In film, Hildegard has been portrayed by Patricia Routledge in a BBC documentary called Hildegard of Bingen (1994),[127] by Ángela Molina in Barbarossa (2009)[128] and by Barbara Sukowa in the film Vision, directed by Margarethe von Trotta.[129]

A feature documentary film, The Unruly Mystic: Saint Hildegard, was released by American director Michael M. Conti in 2014.[130]

Hildegard makes an appearance in The Baby-Sitters Club #101: Claudia Kishi, Middle School Drop-Out by Ann M. Martin, when Anna Stevenson dresses as Hildegard for Halloween.[131]

Kristin Hayter, known professionally as Lingua Ignota, was inspired by Hildegard of Bingen.