Queen of Sheba | |

|---|---|

Queen of Sheba (1907) by Edward Slocombe | |

| Personal | |

| Religion | Religion of Solomon |

| Nationality | Sheba |

| Other names | Makeda |

The Queen of Sheba,[a] also called Bilqis[b] (Yemeni and Islamic tradition) and Makeda[c] (Ethiopian tradition), is a figure first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. In the original story, she brings a caravan of valuable gifts for the Israelite King Solomon. This account has undergone extensive Jewish, Islamic, Yemenite[1][2] and Ethiopian elaborations, and it has become the subject of one of the most widespread and fertile cycles of legends in Asia and Africa.[3]

Modern historians and archaeologists identify Sheba as the ancient South Arabian kingdom of Saba' that existed in modern-day Yemen, although no trace of the queen herself has been found.[4][5] The queen's existence is disputed among some historians.[6]

The Queen of Sheba (Hebrew: מַלְכַּת שְׁבָא, romanized: Malkaṯ Šəḇāʾ,[7] in the Hebrew Bible; Koinē Greek: βασίλισσα Σαβά, romanized: basílissa Sabá, in the Septuagint;[8] Syriac: ܡܠܟܬ ܫܒܐ;[9][romanization needed] Ge'ez: ንግሥተ ሳባ, romanized: Nəgśətä Saba[10]), whose name is not stated, came to Jerusalem "with a very great retinue, with camels bearing spices, and very much gold, and precious stones" (1 Kings 10:2). "Never again came such an abundance of spices" (10:10; 2 Chronicles 9:1–9) as those she gave to Solomon. She came "to prove him with hard questions", which Solomon answered to her satisfaction. They exchanged gifts, after which she returned to her land.[11][12]

The use of the term ḥiddot or 'riddles' (1 Kings 10:1), an Aramaic loanword whose shape points to a sound shift no earlier than the sixth century BC, indicates a late origin for the text.[11] Since there is no mention of the Fall of Babylon in 539 BC, Martin Noth has held that the Book of Kings received a definitive redaction around 550 BC.[13]

Sheba was quite well known in the classical world, and its country was called Arabia Felix.[12] Around the mid-1st millennium BC, there were Sabaeans also in Ethiopia and Eritrea, in the area that later became the realm of Aksum.[14] There are five places in the Bible where the writer distinguishes Sheba (שׁבא), i.e. the Yemenite Sabaeans, from Seba (סבא), i.e. the African Sabaeans. In Ps. 72:10 they are mentioned together: "the kings of Sheba and Seba shall offer gifts".[15] This spelling differentiation, however, may be purely factitious; the indigenous inscriptions make no such difference, and both Yemenite and African Sabaeans are there spelled in exactly the same way.[14]

Although there are still no inscriptions found from South Arabia that furnish evidence for the Queen of Sheba herself, South Arabian inscriptions do mention a South Arabian queen (mlkt, Ancient South Arabian: 𐩣𐩡𐩫𐩩).[1][16] And in the north of Arabia, Assyrian inscriptions repeatedly mention Arab queens.[17] Furthermore, Sabaean tribes knew the title of mqtwyt ("high official", Sabaean: 𐩣𐩤𐩩𐩥𐩺𐩩). Makada or Makueda, the personal name of the queen in Ethiopian legend, might be interpreted as a popular rendering of the title of mqtwyt.[18] This title may be derived from Ancient Egyptian m'kit (𓅖𓎡𓇌𓏏𓏛) "protectress, housewife".[19]

The queen's visit could have been a trade mission.[12][14] Early South Arabian trade with Mesopotamia involving wood and spices transported by camels is attested in the early 9th century BC and may have begun as early as the 10th.[11] A recent theory suggests that the Ophel inscription in Jerusalem was written in the Sabaic language and that the text provides evidence for trade connections between ancient South Arabia and the Kingdom of Judah during the 10th century BC[20]

The ancient Sabaic Awwām Temple, known in folklore as Maḥram ("the Sanctuary of") Bilqīs, was recently excavated by archaeologists, but no trace of the Queen of Sheba has been discovered so far in the many inscriptions found there.[12] Another Sabean temple, the Barran Temple (Arabic: معبد بران), is also known as the 'Arash Bilqis ("Throne of Bilqis"), which like the nearby Awwam Temple was also dedicated to the god Almaqah, but the connection between the Barran Temple and Sheba has not been established archaeologically either.[21]

Bible stories of the Queen of Sheba and the ships of Ophir served as a basis for legends about the Israelites traveling in the Queen of Sheba's entourage when she returned to her country to bring up her child by Solomon.[22]

Christian scriptures mention a "queen of the South" (Greek: βασίλισσα νότου, Latin: Regina austri), who "came from the uttermost parts of the earth", i.e. from the extremities of the then known world, to hear the wisdom of Solomon (Mt. 12:42; Lk. 11:31).[23]

The mystical interpretation of the Song of Songs, which was felt as supplying a literal basis for the speculations of the allegorists, makes its first appearance in Origen, who wrote a voluminous commentary on the Song of Songs.[24] In his commentary, Origen identified the bride of the Song of Songs with the "queen of the South" of the Gospels (i.e., the Queen of Sheba, who is assumed to have been Ethiopian).[25] Others have proposed either the marriage of Solomon with the Pharaoh's daughter, or his marriage with an Israelite woman, the Shulamite. The former was the favorite opinion of the mystical interpreters to the end of the 18th century; the latter has obtained since its introduction by Good (1803).[24]

The bride of the Canticles is assumed to have been black due to a passage in Song of Songs 1:5, which the Revised Standard Version (1952) translates as "I am very dark, but comely", as does Jerome (Latin: Nigra sum, sed formosa), while the New Revised Standard Version (1989) has "I am black and beautiful", as the Septuagint (Ancient Greek: μέλαινα εἰμί καί καλή).[26]

One legend has it that the Queen of Sheba brought Solomon the same gifts that the Magi later gave to Jesus.[27] During the Middle Ages, Christians sometimes identified the queen of Sheba with the sibyl Sabba.[28]

The story of Solomon and the queen was popular among Copts, as shown by fragments of a Coptic legend preserved in a Berlin papyrus. The queen, having been subdued by deceit, gives Solomon a pillar on which all earthly science is inscribed. Solomon sends one of his demons to fetch the pillar from Ethiopia, whence it instantly arrives. In a Coptic poem, queen Yesaba of Cush asks riddles of Solomon.[29]

The most extensive version of the legend appears in the Kebra Nagast (Glory of the Kings), the Ethiopian national saga,[30] translated from Arabic in 1322.[31][32][33] Here Menelik I is the child of Solomon and Makeda (the Ethiopic name for the queen of Sheba; she is the child of the man who destroys the legendary snake-king Arwe[34]) from whom the Ethiopian dynasty claims descent to the present day. While the Abyssinian story offers much greater detail, it omits any mention of the Queen's hairy legs or any other element that might reflect on her unfavourably.[35][36]

Based on the Gospels of Matthew (Matthew 12:42) and Luke (Luke 11:31), the "queen of the South" is claimed to be the queen of Ethiopia. In those times, King Solomon sought merchants from all over the world, in order to buy materials for the building of the Temple. Among them was Tamrin, great merchant of Queen Makeda of Ethiopia. Having returned to Ethiopia, Tamrin told the queen of the wonderful things he had seen in Jerusalem, and of Solomon's wisdom and generosity, whereupon she decided to visit Solomon. She was warmly welcomed, given a palace for dwelling, and received great gifts every day. Solomon and Makeda spoke with great wisdom, and instructed by him, she converted to Judaism. Before she left, there was a great feast in the king's palace. Makeda stayed in the palace overnight, after Solomon had sworn that he would not do her any harm, while she swore in return that she would not steal from him. As the meals had been spicy, Makeda awoke thirsty at night and went to drink some water, when Solomon appeared, reminding her of her oath. She answered: "Ignore your oath, just let me drink water."

That same night, Solomon had a dream about the sun rising over Israel, but being mistreated and despised by the Jews, the sun moved to shine over Ethiopia and Rome. Solomon gave Makeda a ring as a token of faith, and then she left. On her way home, she gave birth to a son, whom she named Baina-leḥkem (i.e. bin al-ḥakīm, "Son of the Wise Man", later called Menilek). After the boy had grown up in Ethiopia, he went to Jerusalem carrying the ring and was received with great honors. The king and the people tried in vain to persuade him to stay. Solomon gathered his nobles and announced that he would send his first-born son to Ethiopia together with their first-borns. He added that he was expecting a third son, who would marry the king of Rome's daughter and reign over Rome so that the entire world would be ruled by David's descendants. Then Baina-leḥkem was anointed king by Zadok the high priest, and he took the name David. The first-born nobles who followed him are named, and even today some Ethiopian families claim their ancestry from them. Prior to leaving, the priests' sons had stolen the Ark of the Covenant, after their leader Azaryas had offered a sacrifice as commanded by one God's angel. With much wailing, the procession left Jerusalem on a wind cart led and carried by the archangel Michael. Having arrived at the Red Sea, Azaryas revealed to the people that the Ark is with them. David prayed to the Ark and the people rejoiced, singing, dancing, blowing horns and flutes, and beating drums. The Ark showed its miraculous powers during the crossing of the stormy Sea, and all arrived unscathed. When Solomon learned that the Ark had been stolen, he sent a horseman after the thieves and even gave chase himself, but neither could catch them. Solomon returned to Jerusalem and gave orders to the priests to remain silent about the theft and to place a copy of the Ark in the Temple, so that the foreign nations could not say that Israel had lost its fame.[37][38]

According to some sources, Queen Makeda was part of the dynasty founded by Za Besi Angabo in 1370 BC. The family's intended choice to rule Aksum was Makeda's brother, Prince Nourad, but his early death led to her succession to the throne. She apparently ruled the Ethiopian kingdom for more than 50 years.[39] The 1922 regnal list of Ethiopia claims that Makeda reigned from 1013 to 982 BC, with dates following the Ethiopian calendar.[40]

In the Ethiopian Book of Aksum, Makeda is described as establishing a new capital city at Azeba.[41]

Edward Ullendorff holds that Makeda is a corruption of Candace, the name or title of several Ethiopian queens from Meroe or Seba. Candace was the name of that queen of the Ethiopians whose chamberlain was converted to Christianity under the preaching of Philip the Evangelist (Acts 8:27) in 30 AD. In the 14th-century (?) Ethiopic version of the Alexander romance, Alexander the Great of Macedonia (Ethiopic Meqédon) is said to have met a queen Kandake of Nubia.[42] The tradition that the biblical Queen of Sheba was an ingenuous ruler of Ethiopia who visited King Solomon in Jerusalem is repeated in a 1st-century account by Josephus. He identified Solomon's visitor as a queen of Egypt and Ethiopia

Historians believe that the Solomonic dynasty actually began in 1270 with the emperor Yekuno Amlak, who, with the support of the Ethiopian Church, overthrew the Zagwe dynasty, which had ruled Ethiopia since sometime during the 10th century. The link to King Solomon provided a strong foundation for Ethiopian national unity. "Ethiopians see their country as God's chosen country, the final resting place that he chose for the Ark – and Sheba and her son were the means by which it came there".[43] Despite the fact that the dynasty officially ended in 1769 with Emperor Iyoas, Ethiopian rulers continued to trace their connection to it, right up to the last 20th-century emperor, Haile Selassie.[44]

According to one tradition, the Ethiopian Jews (Beta Israel, "Falashas") also trace their ancestry to Menelik I, son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.[45] An opinion that appears more historical is that the Falashas descend from those Jews who settled in Egypt after the first exile, and who, upon the fall of the Persian domination (539–333 BC), on the borders of the Nile, penetrated into the Sudan, whence they went into the western parts of Abyssinia.[46]

Several emperors have stressed the importance of the Kebra Negast. One of the first instances of this can be traced in a letter from Prince Kasa (King John IV) to Queen Victoria in 1872.[47] Kasa states, "There is a book called Kebra Nagast which contains the law of the whole of Ethiopia, and the names of the shums (governors), churches and provinces are in this book. I pray you will find out who has got this book and send it to me, for in my country my people will not obey my orders without it."[43] Despite the historic importance given to the Kebra Negast, there is still doubt to whether or not the Queen sat on the throne.

According to Josephus (Ant. 8:165–173), the queen of Sheba was the queen of Egypt and Ethiopia, and brought to Israel the first specimens of the balsam, which grew in the Holy Land in the historian's time.[12][48] Josephus (Antiquities 2.5‒10) represents Cambyses as conquering the capital of Aethiopia, and changing its name from Seba to Meroe.[49] Josephus affirms that the Queen of Sheba or Saba came from this region, and that it bore the name of Saba before it was known by that of Meroe. There seems also some affinity between the word Saba and the name or title of the kings of the Aethiopians, Sabaco.[50][obsolete source]

The Talmud (Bava Batra 15b) insists that it was not a woman but a kingdom of Sheba (based on varying interpretations of Hebrew mlkt) that came to Jerusalem. Baba Bathra 15b: "Whoever says malkath Sheba (I Kings X, 1) means a woman is mistaken; ... it means the kingdom (מַלְכֻת) of Sheba".[51] This is explained to mean that she was a woman who was not in her position because of being married to the king, but through her own merit.[52]

The most elaborate account of the queen's visit to Solomon is given in the Targum Sheni to Esther (see: Colloquy of the Queen of Sheba). A hoopoe informed Solomon that the kingdom of Sheba was the only kingdom on earth not subject to him and that its queen was a sun worshiper. He thereupon sent it to Kitor in the land of Sheba with a letter attached to its wing commanding its queen to come to him as a subject. She thereupon sent him all the ships of the sea loaded with precious gifts and 6,000 youths of equal size, all born at the same hour and clothed in purple garments. They carried a letter declaring that she could arrive in Jerusalem within three years although the journey normally took seven years. When the queen arrived and came to Solomon's palace, thinking that the glass floor was a pool of water, she lifted the hem of her dress, uncovering her legs. Solomon informed her of her mistake and reprimanded her for her hairy legs. She asked him three (Targum Sheni to Esther 1:3) or, according to the Midrash (Prov. ii. 6; Yalḳ. ii., § 1085, Midrash ha-Hefez), more riddles to test his wisdom.[3][11][12][48]

A Yemenite manuscript entitled "Midrash ha-Hefez" (published by S. Schechter in Folk-Lore, 1890, pp. 353 et seq.) gives nineteen riddles, most of which are found scattered through the Talmud and the Midrash, which the author of the "Midrash ha-Hefez" attributes to the Queen of Sheba.[53] Most of these riddles are simply Bible questions, some not of a very edifying character. The two that are genuine riddles are: "Without movement while living, it moves when its head is cut off", and "Produced from the ground, man produces it, while its food is the fruit of the ground". The answer to the former is, "a tree, which, when its top is removed, can be made into a moving ship"; the answer to the latter is, "a wick".[54]

The rabbis who denounce Solomon interpret 1 Kings 10:13 as meaning that Solomon had criminal intercourse with the Queen of Sheba, the offspring of which was Nebuchadnezzar, who destroyed the Temple (comp. Rashi ad loc.). According to others, the sin ascribed to Solomon in 1 Kings 11:7 et seq. is only figurative: it is not meant that Solomon fell into idolatry, but that he was guilty of failing to restrain his wives from idolatrous practises (Shab. 56b).[53]

The Alphabet of Sirach avers that Nebuchadnezzar was the fruit of the union between Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.[3] In the Kabbalah, the Queen of Sheba was considered one of the queens of the demons and is sometimes identified with Lilith, first in the Targum of Job (1:15), and later in the Zohar and the subsequent literature. A Jewish and Arab myth maintains that the Queen was actually a jinn, half-human and half-demon.[55][56]

In Ashkenazi folklore, the figure merged with the popular image of Helen of Troy or the Frau Venus of German mythology. Ashkenazi incantations commonly depict the Queen of Sheba as a seductive dancer. Until recent generations, she was popularly pictured as a snatcher of children and a demonic witch.[56]

The Temple of Awwam or "Mahram Bilqis" ("Sanctuary of the Queen of Sheba") is a Sabaean temple dedicated to the principal deity of Saba, Almaqah (frequently called "Lord of ʾAwwām"), near Ma'rib in what is now Yemen.

I found [there] a woman ruling them, and she has been given of all things, and she has a great throne. I found that she and her people bow to the sun instead of God. Satan has made their deeds seem right to them and has turned them away from the right path, so they cannot find their way.

In the above verse (ayah), after scouting nearby lands, a bird known as the hud-hud (hoopoe) returns to King Solomon relating that the land of Sheba is ruled by a Queen. In a letter, Solomon invites the Queen of Sheba, who like her followers had worshipped the sun, to submit to God. She expresses that the letter is noble and asks her chief advisers what action should be taken. They respond by mentioning that her kingdom is known for its might and inclination towards war, however that the command rests solely with her. In an act suggesting the diplomatic qualities of her leadership,[58] she responds not with brute force, but by sending her ambassadors to present a gift to King Solomon. He refuses the gift, declaring that God gives far superior gifts and that the ambassadors are the ones only delighted by the gift. King Solomon instructs the ambassadors to return to the Queen with a stern message that if he travels to her, he will bring a contingent that she cannot defeat. The Queen then makes plans to visit him at his palace. Before she arrives, King Solomon asks several of his chiefs who will bring him the Queen of Sheba's throne before they come to him in complete submission.[59] An Ifrit first offers to move her throne before King Solomon would rise from his seat.[60] However, a man with knowledge of the Scripture instead has her throne moved to King Solomon's palace in the blink of an eye, at which King Solomon exclaims his gratitude towards God as King Solomon assumes this is God's test to see if King Solomon is grateful or ungrateful.[61] King Solomon disguises her throne to test her awareness of her own throne, asking her if it seems familiar. She answers that during her journey to him, her court had informed her of King Solomon's prophethood, and since then she and her subjects had made the intention to submit to God. King Solomon then explains that God is the only god that she should worship, not to be included alongside other false gods that she used to worship. Later the Queen of Sheba is requested to enter a palatial hall. Upon first view she mistakes the hall for a lake and raises her skirt to not wet her clothes. King Solomon informs her that is not water rather it is smooth slabs of glass. Recognizing that it was a marvel of construction which she had not seen the likes of before, she declares that in the past she had harmed her own soul but now submits, with King Solomon, to God (27:22–44).[62]

She was told, "Enter the palace." But when she saw it, she thought it was a body of water and uncovered her shins [to wade through]. He said, "Indeed, it is a palace [whose floor is] made smooth with glass." She said, "My Lord, indeed I have wronged myself, and I submit with Solomon to God, Lord of the worlds."

The story of the Queen of Sheba in the Quran shares some similarities with the Bible and other Jewish sources.[12] Some Muslim commentators such as Al-Tabari, Al-Zamakhshari and Al-Baydawi supplement the story. Here they claim that the Queen's name is Bilqīs (Arabic: بِلْقِيْس), probably derived from Greek: παλλακίς, romanized: pallakis or the Hebraised pilegesh ("concubine"). The Quran does not name the Queen, referring to her as "a woman ruling them" (Arabic: امْرَأَةً تَمْلِكُهُمْ),[64] the nation of Sheba.[65]

According to some, he then married the Queen, while other traditions say that he gave her in marriage to a King of Hamdan.[3] According to the scholar Al-Hamdani, the Queen of Sheba was the daughter of Ilsharah Yahdib, the Sabaean king of South Arabia.[18] In another tale, she is said to be the daughter of a jinni (or peri)[66] and a human.[67] According to E. Ullendorff, the Quran and its commentators have preserved the earliest literary reflection of her complete legend, which among scholars complements the narrative that is derived from a Jewish tradition,[3] this assuming to be the Targum Sheni. However, according to the Encyclopaedia Judaica Targum Sheni is dated to around 700[68] similarly the general consensus is to date Targum Sheni to late 7th- or early 8th century,[69] which post-dates the advent of Islam by almost 200 years. Furthermore, M. J. Berdichevsky[70] explains that this Targum is the earliest narrative articulation of Queen of Sheba in Jewish tradition.

The Yoruba Ijebu clan of Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria, claim that she was a wealthy, childless noblewoman of theirs known as Oloye Bilikisu Sungbo. They also assert that a medieval system of walls and ditches, known as the Eredo and built sometime around the 10th century CE, was dedicated to her.

After excavations in 1999 the archaeologist Patrick Darling, known as “the architect”, was quoted as saying, "I don't want to overplay the Sheba theory, but it cannot be discounted ... The local people believe it and that's what is important ... The most cogent argument against it at the moment is the dating."[71]

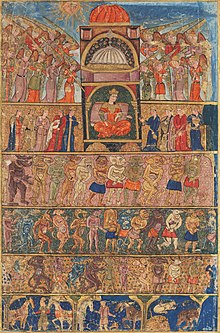

The treatment of Solomon in literature, art, and music also involves the sub-themes of the Queen of Sheba and the Shulammite of the Song of Songs. King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba was not a common subject until the 12th century. In Christian iconography Solomon represented Jesus, and Sheba represented the gentile Church; hence Sheba's meeting with Solomon bearing rich gifts foreshadowed the adoration of the Magi. On the other hand, Sheba enthroned represented the coronation of the virgin.[11]

Sculptures of the Queen of Sheba are found on great Gothic cathedrals such as Chartres, Rheims, Amiens, and Wells.[11] The 12th century cathedrals at Strasbourg, Chartres, Rochester and Canterbury include artistic renditions in stained glass windows and doorjamb decorations.[72] Likewise of Romanesque art, the enamel depiction of a black woman at Klosterneuburg Monastery.[73] The Queen of Sheba, standing in water before Solomon, is depicted on a window in King's College Chapel, Cambridge.[3]

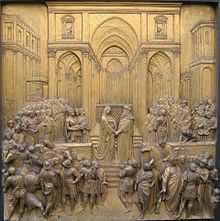

The reception of the queen was a popular subject during the Italian Renaissance. It appears in the bronze doors to the Florence Baptistery by Lorenzo Ghiberti, in frescoes by Benozzo Gozzoli (Campo Santo, Pisa) and in the Raphael Loggie (Vatican). Examples of Venetian art are by Tintoretto (Prado) and Veronese (Pinacotheca, Turin). In the 17th century, Claude Lorrain painted The Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba (National Gallery, London).[11]

Piero della Francesca's frescoes in Arezzo (c. 1466) on the Legend of the True Cross contain two panels on the visit of the Queen of Sheba to Solomon. The legend links the beams of Solomon's palace (adored by Queen of Sheba) to the wood of the crucifixion. The Renaissance continuation of the analogy between the Queen's visit to Solomon and the adoration of the Magi is evident in the Triptych of the Adoration of the Magi (c. 1510) by Hieronymus Bosch.[74]

Boccaccio's On Famous Women (Latin: De Mulieribus Claris) follows Josephus in calling the Queen of Sheba Nicaula. Boccaccio writes she is the Queen of Ethiopia and Egypt, and that some people say she is also the queen of Arabia. He writes that she had a palace on "a very large island" called Meroe, located in the Nile river. From there Nicaula travelled to Jerusalem to see King Solomon.[75]

O. Henry's short story The Gift of the Magi contains the following description to convey the preciousness of the protagonist Della Dillingham Young's hair: "Had the queen of Sheba lived in the flat across the airshaft, Della would have let her hair hang out the window some day to dry just to depreciate Her Majesty's jewels and gifts."

Christine de Pizan's The Book of the City of Ladies continues the convention of calling the Queen of Sheba "Nicaula". The author praises the Queen for secular and religious wisdom and lists her besides Christian and Hebrew prophetesses as first on a list of dignified female pagans.[citation needed]

Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus refers to the Queen of Sheba as Saba, when Mephistopheles is trying to persuade Faustus of the wisdom of the women with whom he supposedly shall be presented every morning.[76]

Gérard de Nerval's autobiographical novel, Voyage to the Orient (1851), details his travels through the Middle East with much artistic license. He recapitulates at length a tale told in a Turkish cafe of King Soliman's love of Balkis, the Queen of Saba, but she, in turn, is destined to love Adoniram (Hiram Abif), Soliman's chief craftsman of the Temple, owing to both her and Adoniram's divine genealogy. Soliman grows jealous of Adoniram, and when he learns of three craftsmen who wish to sabotage his work and later kill him, Soliman willfully ignores warnings of these plots. Adoniram is murdered and Balkis flees Soliman's kingdom.[77]

Léopold Sédar Senghor's "Elégie pour la Reine de Saba", published in his Elégies majeures in 1976, uses the Queen of Sheba in a love poem and for a political message. In the 1970s, he used the Queen of Sheba fable to widen his view of Negritude and Eurafrique by including "Arab-Berber Africa".[78]

Rudyard Kipling's book Just So Stories includes the tale of The Butterfly that Stamped. Therein, Kipling identifies Balkis, "Queen that was of Sheba and Sable and the Rivers of the Gold of the South" as best, and perhaps only, beloved of the 1000 wives of Suleiman-bin-Daoud, King Solomon. She is explicitly ascribed great wisdom ("Balkis, almost as wise as the Most Wise Suleiman-bin-Daoud"); nevertheless, Kipling perhaps implies in her a greater wisdom than her husband, in that she is able to gently manipulate him, the afrits and djinns he commands, the other quarrelsome 999 wives of Suleimin-bin-Daoud, the butterfly of the title and the butterfly's wife, thus bringing harmony and happiness for all.

The Queen of Sheba appears as a character in The Ring of Solomon, the fourth book in Jonathan Stroud's Bartimaeus Sequence. She is portrayed as a vain woman who, fearing Solomon's great power, sends the captain of her royal guard to assassinate him, setting the events of the book in motion.

In modern popular culture, she is often invoked as a sarcastic retort to a person with an inflated sense of entitlement, as in "Who do you think you are, the Queen of Sheba?"[79]

It seems that the most acceptable view is that which places its composition at the end of the seventh or the beginning of the eighth century, a view that is strengthened by its relationship to the Pirkei de-R. Eliezer

Targum Scheni :Jetzt können wir unsere Aufmerksamkeit kurz der zweiten Haupttradition der Esther Targume zuwenden, die als Targum Scheni bekannt ist. Dieses Werk stammt vom Ende des 7. oder Anfang des 8. Jahrhunderts. /// Translation: This work (Targum Sheni) dates to the end of the 7th or beginning of the 8th century

The present text, a translation of a story that occurs in Targum Sheni of the Book Esther, dates from the seventh to early eighth century and is the earliest narrative articulation of the Queen of Sheba in Jewish tradition

People and things in the Quran | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Note: Names are sorted alphabetically. Standard form: Islamic name / Biblical name (title or relationship) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Islamic honored women | |

|---|---|

| Generations of Adam | |

| Generations of Ibrāhīm and his sons | |

| Generation of Mūsa | |

| Reign of Kings | |

| House of Imran | |

| Time of Muhammad | |

| Family and reputed relations | |

|---|---|

| Occurrences | |

| Reputed works |

|

| Related articles | |

| Bible chapters | |

|---|---|

| Places | |

| People | |

| Phrases | |

| Analysis | |

| In art | |

| Manuscripts | |

| Sources | |

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| People | |