| Thutmose I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thutmosis, Tuthmosis, Thothmes in Latinized Greek | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

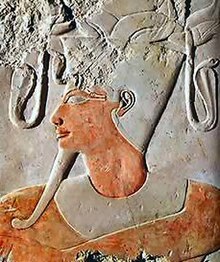

A stone head, most likely depicting Thutmose I, at the British Museum | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 12 yrs; 1506–1493 BC (low chronology); 1526 BC to 1513 BC (high chronology) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Amenhotep I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Thutmose II | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Ahmose Mutnofret | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Thutmose II Hatshepsut Amenmose Wadjmose Nefrubity | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Unknown (possibly Amenhotep I or Ahmose Sapair) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Senseneb | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 1493 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | KV20, later KV38; Mummy found in the Deir el-Bahri royal cache (Theban Necropolis) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments | Pylons IV and V, two obelisks, and a hypostyle hall at Karnak | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | 18th Dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Thutmose I (sometimes read as Thutmosis or Tuthmosis I, Thothmes in older history works in Latinized Greek; meaning "Thoth is born") was the third pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. He received the throne after the death of the previous king, Amenhotep I. During his reign, he campaigned deep into the Levant and Nubia, pushing the borders of Egypt farther than ever before in each region. He also built many temples in Egypt, and a tomb for himself in the Valley of the Kings; he is the first king confirmed to have done this (though Amenhotep I may have preceded him).

Thutmose I's reign is generally dated to 1506–1493 BC, but a minority of scholars—who think that astrological observations used to calculate the timeline of ancient Egyptian records, and thus the reign of Thutmose I, were taken from the city of Memphis rather than from Thebes—would date his reign to 1526–1513 BC.[2][3] He was succeeded by his son Thutmose II, who in turn was succeeded by Thutmose II's sister, Hatshepsut.

|

See also: Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt family tree |

It has been speculated that Thutmose's father was Amenhotep I. His mother, Senseneb, was of non-royal parentage and may have been a lesser wife or concubine.[4] Queen Ahmose, who held the title of Great Royal Wife of Thutmose, was probably the daughter of Ahmose I and the sister of Amenhotep I;[5] however, she was never called "king's daughter," so there is some doubt about this, and some historians believe that she was Thutmose's own sister.[6] Assuming she was related to Amenhotep, it could be thought that she was married to Thutmose in order to guarantee succession. However, this is known not to be the case for two reasons. Firstly, Amenhotep's alabaster bark built at Karnak associates Amenhotep's name with Thutmose's name well before Amenhotep's death.[7] Secondly, Thutmose's first-born son with Ahmose, Amenmose, was apparently born long before Thutmose's coronation. He can be seen on a stela from Thutmose's fourth regnal year hunting near Memphis, and he became the "great army-commander of his father" sometime before his death, which was no later than Thutmose's own death in his 12th regnal year.[8] Thutmose had another son, Wadjmose, and two daughters, Hatshepsut and Nefrubity, by Ahmose. Wadjmose died before his father, and Nefrubity died as an infant.[9]

Thutmose had also one son by his another wife, Mutnofret, who was likely a daughter of Ahmose I and a sister of Amenhotep I.[10]. This son succeeded him as Thutmose II, whom Thutmose I married to his daughter, Hatshepsut.[9] It was later recorded by Hatshepsut that Thutmose willed the kingship to both Thutmose II and Hatshepsut. However, this is considered to be propaganda by Hatshepsut's supporters to legitimise her claim to the throne when she later assumed power.[11]

A heliacal rising of Sothis was recorded in the reign of Thutmose's predecessor, Amenhotep I, which has been dated to 1517 BC, assuming the observation was made at Thebes.[12] The year of Amenhotep's death and Thutmose's subsequent coronation can be accordingly derived, and is dated to 1506 BC by most modern scholars. However, if the observation were made at either Heliopolis or Memphis, as a minority of scholars promote, Thutmose would have been crowned in 1526 BC.[13] Manetho records that Thutmose I's reign lasted 12 Years and 9 Months (or 13 Years) as a certain Mephres in his Epitome.[14] This data is supported by two dated inscriptions from Years 8 and 9 of his reign bearing his cartouche found inscribed on a stone block in Karnak.[15] Accordingly, Thutmose is usually given a reign from 1506 BC to 1493 BC (low chronology), but a minority of scholars would date him from 1526 BC to 1513 BC (high chronology).[12]

Upon Thutmose's coronation, Nubia rebelled against Egyptian rule. According to the tomb autobiography of Ahmose, son of Ebana, Thutmose traveled up the Nile and fought in the battle, personally killing the Nubian king.[16] Upon victory, he had the Nubian king's body hung from the prow of his ship, before he returned to Thebes.[16] After that campaign, he led a second expedition against Nubia in his third year in the course of which he ordered the canal at the first cataract—which had been built under Sesostris III of the 12th Dynasty—to be dredged in order to facilitate easier travel upstream from Egypt to Nubia. This helped integrate Nubia into the Egyptian empire.[9] This expedition is mentioned in two separate inscriptions by the king's son Thure:[17]

Year 3, first month of the third season, day 22, under the majesty of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Aakheperre who is given life. His Majesty commanded to dig this canal after he found it stopped up with stones [so that] no [ship sailed upon it]; Year 3, first month of the third season, day 22. His Majesty sailed this canal in victory and in the power of his return from overthrowing the wretched Kush.[18]

In the second year of Thutmose's reign, the king cut a stele at Tombos, which records that he built a fortress at Tombos, near the third cataract, thus permanently extending the Egyptian military presence, which had previously stopped at Buhen, at the second cataract.[19]

Thutmose's Tombos stele indicates that he had already fought a campaign in Syria; hence, his Syrian campaign may be placed at the beginning of his second regnal year.[20] This second campaign was the farthest north any Egyptian ruler had ever campaigned.

Although it has not been found in modern times, he apparently set up a stele when he crossed the Euphrates River.[21] During this campaign, the Syrian princes declared allegiance to Thutmose. However, after he returned, they discontinued tribute and began fortifying against future incursions.[9] Thutmose celebrated his victories with an elephant hunt in the area of Niy, near Apamea in Syria,[8] and returned to Egypt with strange tales of the Euphrates, "that inverted water which flows upstream when it ought to be flowing downstream."[9] The Euphrates was the first major river which the Egyptians had ever encountered which flowed from the north, which was downstream on the Nile, to the south, which was upstream on the Nile. Thus the river became known in Egypt as simply, "inverted water."[9]

Textual sources from the time of Thutmose I include references to Retenu, Naharin, and the 'land of Mitanni'. The last is believed to be the first historical reference to that kingdom.[22]

Many Levantine sites were destroyed in the middle of the 16th century B.C., and these destructions have often been attributed to the military campaigns of Thutmose I, or of his predecessor Amenhotep I. Initially these campaigns may have aimed at defeating the power of the Hyksos, who were strong in this area previously.[22]

As many as 20 sites in the Levant suffered destruction at this time. For example, the fiery destruction of Stratum XVIII at Gezer has been assigned to the second half of 16th century, the time of Amenhotep I and Thutmose I. This is based on the pottery and scarabs discovered in the destruction debris.[22]

It does not appear that the aim of the Egyptians at this stage was to control the area permanently, because they did not establish any permanent presence in the area. This was to come later on during 18th dynasty.[22]

Thutmose had to face one more military threat, another rebellion by Nubia in his fourth year.[20] His influence accordingly expanded even farther south, as an inscription dated to his reign has been found as far south as Kurgus, which was south of the fourth cataract.[21] He inscribed a large tableau on the Hagar el-Merwa, a quartz outcrop c. 40m long and 50m wide located 1200m from the Nile, on top of several local inscriptions.[23] This is the furthest south the Egyptian presence is attested.[23] During his reign, he initiated a number of projects which effectively ended Nubian independence for the next 500 years. He enlarged a temple to Sesostris III and Khnum, opposite the Nile from Semna.[24] There are also records of specific religious rites which the viceroy of El-Kab was to have performed in the temples in Nubia in proxy for the king.[25] He also appointed a man called Turi to the position of viceroy of Kush, also known as the "King's Son of Cush."[26] With a civilian representative of the king permanently established in Nubia itself, Nubia did not dare to revolt as often as it had and was easily controlled by future Egyptian kings.[20]

Thutmose I organized great building projects during his reign, including many temples and tombs, but his greatest projects were at the Temple of Karnak under the supervision of the architect Ineni.[27] Previous to Thutmose, Karnak probably consisted only of a long road to a central platform, with a number of shrines for the solar bark along the side of the road.[28] Thutmose was the first king to drastically enlarge the temple. He had the fifth pylon built along the temple's main road, along with a wall to run around the inner sanctuary and two flagpoles to flank the gateway.[28] Outside of this, he built a fourth pylon and another enclosure wall.[28] Between pylons four and five, he had a hypostyle hall constructed, with columns made of cedar wood. This type of structure was common in ancient Egyptian temples, and supposedly represents a papyrus marsh, an Egyptian symbol of creation.[29] Along the edge of this room he built colossal statues, each one alternating wearing the crown of Upper Egypt and the crown of Lower Egypt.[28] Finally, outside of the fourth pylon, he erected four more flagpoles[28] and two obelisks, although one of them, which now has fallen, was not inscribed until Thutmose III inscribed it about 50 years later.[27] The cedar columns in Thutmose I's hypostyle hall were replaced with stone columns by Thutmose III, however at least the northernmost two were replaced by Thutmose I himself.[27] Hatshepsut also erected two of her own obelisks inside of Thutmose I's hypostyle hall.[28]

In addition to Karnak, Thutmose I also built statues of the Ennead at Abydos, buildings at Armant, Ombos, el-Hiba, Memphis, and Edfu, as well as minor expansions to buildings in Nubia, at Semna, Buhen, Aniba, and Quban.[citation needed]

Thutmose I was the first king who definitely was buried in the Valley of the Kings.[21] Ineni was commissioned to dig this tomb, and presumably to build his mortuary temple.[8] His mortuary temple has not been found, quite possibly because it was incorporated into or demolished by the construction of Hatshepsut's mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri.[30] His tomb, however, has been identified as KV38. In it was found a yellow quartzite sarcophagus bearing the name of Thutmose I.[5] His body, however, may have been moved by Thutmose III into the tomb of Hatshepsut, KV20, which also contains a sarcophagus with the name of Thutmose I on it.[21]

Thutmose I was originally buried and then reburied in KV20 in a double burial with his daughter Hatshepsut rather than KV38, which could only have been built for Thutmose I during the reign of his grandson Thutmose III based on "a recent re-examination of the architecture and contents of KV38."[31] The location of KV20, if not its original owner, had long been known since the Napoleonic expedition of 1799 and, in 1844, the Prussian scholar Karl Richard Lepsius had partially explored its upper passage.[32] However, all its passageways "had become blocked by a solidified mass of rubble, small stones and rubbish which had been carried into the tomb by floodwaters" and it was not until the 1903–1904 excavation season that Howard Carter, after two previous seasons of strenuous work, was able to clear its corridors and enter its double burial chamber.[32] Here, among the debris of broken pottery and shattered stone vessels from the burial chamber and lower passages were the remnants of two vases made for Queen Ahmose Nefertari, which formed part of the original funerary equipment of Thutmose I; one of the vases contained a secondary inscription which states that Thutmose II "[made it] as his monument to his father."[33] Other vessels which bore the names and titles of Thutmose I had also been inscribed by his son and successor, Thutmose II, as well as fragments of stone vessels made for Hatshepsut before she herself became king as well as other vessels which bore her royal name of 'Maatkare', which would have been made only after she took the throne in her own right.[34]

Carter, however, also discovered 2 separate coffins in the burial chamber. The beautifully carved sarcophagus of Hatshepsut "was discovered open with no sign of a body, and with the lid lying discarded on the floor;" it is now housed in the Cairo Museum along with a matching yellow quartzite canopic chest.[34] A second sarcophagus was found lying on its side with its almost undamaged lid propped against the wall nearby; it was eventually presented to Theodore M. Davis, the excavation's financial sponsor as a gesture of appreciation for his generous financial support.[34] Davis would, in turn, present it to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The second quartzite sarcophagus had originally been engraved with the name of "the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Maatkare Hatshepsut."[34] However, when the sarcophagus was complete, Hatshepsut decided to commission an entirely new sarcophagus for herself while she donated the existing finished sarcophagus to her father, Thutmose I.[34] The stonemasons then attempted to erase the original carvings by restoring the surface of the quartzite so that it could be re-carved with the name and titles of Tuthmose I instead. This quartzite sarcophagus measures 7 feet long by 3 feet wide with walls 5 inches thick and bears a dedication text which records Hatshepsut's generosity towards her father:

...long live the Female Horus...The king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Maatkare, the son of Re, Hatshepsut-Khnemet-Amun! May she live forever! She made it as her monument to her father whom she loved, the Good God, Lord of the Two Lands, Aakheperkare, the son of Re, Thutmosis the justified.[35]

Thutmose I was, however, not destined to lie alongside his daughter after Hatshepsut's death. Thutmose III, Hatshepsut's successor, decided to reinter his grandfather in an even more magnificent tomb, KV38, which featured another yellow sarcophagus dedicated to Thutmose I and inscribed with texts which proclaimed this pharaoh's love for his deceased grandfather.[36] Unfortunately, however, Thutmose I's remains would be disturbed late during the 20th dynasty when KV38 was plundered; the sarcophagus' lid was broken and all this king's valuable precious jewelry and grave goods were stolen.[36]

Thutmose I's mummy was ultimately discovered in the Deir el-Bahri Cache above the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, revealed in 1881. He had been interred along with those of other 18th and 19th dynasty leaders Ahmose I, Amenhotep I, Thutmose II, Thutmose III, Ramesses I, Seti I, Ramesses II, and Ramesses IX, as well as the 21st dynasty pharaohs Pinedjem I, Pinedjem II, and Siamun.

The original coffin of Thutmose I was taken over and re-used by a later pharaoh of the 21st dynasty. The mummy of Thutmose I was thought to be lost, but Egyptologist Gaston Maspero, largely on the strength of familial resemblance to the mummies of Thutmose II and Thutmose III, believed he had found his mummy in the otherwise unlabelled mummy #5283.[38] This identification has been supported by subsequent examinations, revealing that the embalming techniques used came from the appropriate period of time, almost certainly after that of Ahmose I and made during the course of the Eighteenth dynasty.[39]

Gaston Maspero described the mummy in the following manner:

The king was already advanced in age at the time of his death, being over fifty years old, to judge by the incisor teeth, which are worn and corroded by the impurities of which the Egyptian bread was full. The body, though small and emaciated, shows evidence of unusual muscular strength; the head is bald, the features are refined, and the mouth still bears an expression characteristic of shrewdness and cunning.[38]

James Harris and Fawzia Hussien (1991) conducted an X-ray survey on New Kingdom royal mummies and examined the mummified remains of Thutmose I. The results of the study determined that the mummy of Thutmose I had all the craniofacial characteristics common among Nubian populations and a “typical Nubian morphology”.[40]

A 2020 genetic study performed by a team under Zahi Hawass on the Amarna royal mummies also featured the unidentified royal mummy previously thought to be Thutmose I in the control samples. The results of the study indicated that the mummy belonged to the haplogroup L which is mainly observed in southern, western and central Asia (highest in the Indian subcontinent).[41]

What was thought to be his mummy could be viewed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. However, in 2007, Dr. Zahi Hawass announced that the mummy which was previously thought to be Thutmose I is that of a thirty-year-old man who had died as a result of an arrow wound to the chest. Because of the young age of the mummy and the cause of death, it was determined that the mummy was probably not that of King Thutmose I himself.[42] The mummy has the inventory number CG 61065.[43] In April 2021 the mummy was moved to National Museum of Egyptian Civilization along with those of 17 kings and 4 queens in an event termed the Pharaohs' Golden Parade.[44]