Generalissimo, Prince Alexander Suvorov Rymniksky | |

|---|---|

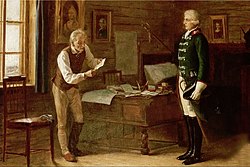

Alexander Suvorov by Charles de Steuben (1815) | |

| Native name | Александр Васильевич Суворов |

| Other name(s) | Aleksandr Vasilevich Suvorov[1] |

| Nickname(s) |

|

| Born | November 24, 1730 Moscow, Moscow Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | May 18, 1800 (aged 69) St. Petersburg, Saint Petersburg Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Buried | Annunciation Church, Alexander Nevsky Lavra, St. Petersburg 59°55′15″N 30°23′17″E / 59.92093°N 30.38800°E |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1745–1800 |

| Rank | Generalissimus (Russian Empire) Feldmarschall (Holy Roman Empire) |

| Commands held | 11th Fanagoriysky Grenadier Regiment Coalition Forces in Italy |

| Battles/wars | See: § Military record |

| Awards | See: § Progeny and titles |

| Alma mater | First Cadet Corps |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Arkady Suvorov Natalya Zubova [ru] |

| Signature | |

| Coat of arms of Count Suvorov-Rymniksky, Prince of Italy | |

|---|---|

|

Count Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov-Rymniksky, Prince of Italy[2][a] (24 November [O.S. 13 November] 1729 or 1730 – 18 May [O.S. 6 May] 1800; Russian: Князь Италийский граф Александр Васильевич Суворов-Рымникский, romanized: Kni͡az' Italiyskiy graf Aleksandr Vasil'yevič Suvorov-Rymnikskiy; IPA: [ɐlʲɪkˈsandr vɐˈsʲilʲjɪvʲɪtɕ sʊˈvorəf]), was a Russian general and military theorist in the service of the Russian Empire.

Born in Moscow, he studied military history as a young boy and joined the Imperial Russian Army at the age of 17. Promoted to colonel in 1762 for his successes during the Seven Years' War, his victories during the War of the Bar Confederation included the capture of Kraków and victories at Orzechowo, Lanckorona, and Stołowicze. His reputation rose further when, in the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774, he captured Turtukaya twice and won a decisive victory at Kozludzha. After a period of little progress, he was promoted to general and led Russian forces in the Russo-Turkish War of 1787–1792, participating in the siege of Ochakov, as well as victories at Kinburn and Focșani.

Suvorov won a decisive victory at the Battle of Rymnik, and afterwards defeated the Ottomans in the storming of Izmail. His victories at Focșani and Rymnik established him as the most brilliant general in Russia, if not in all of Europe.[3] In 1794, he put down the Polish uprising, defeating them at the battle of Praga and elsewhere. After Catherine the Great died in 1796, her successor Paul I often quarrelled with Suvorov. After a period of ill-favour, Suvorov was recalled to a field marshal position at the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars. He was given command of the Austro-Russian army, and after a series of victories, such as the battle of the Trebbia, he captured Milan and Turin, and nearly erased all of Napoleon's Italian conquests of 1796–97.[4][5] After an Austro-Russian army was defeated in Switzerland, Suvorov, ordered to reinforce them, was cut off by André Masséna and later surrounded in the Swiss Alps. His successful extraction of the exhausted, ill-supplied, and heavily-outnumbered Russian army was rewarded by a promotion to Generalissimo. Masséna himself would later confess that he would exchange all of his victories for Suvorov's passage of the Alps.[6] Suvorov died in 1800 of illness in Saint Petersburg. He was instrumental in expanding the Russian Empire, as his success ensured Russia's conquering of Kuban, Crimea, and New Russia.[7]

One of the foremost generals in all of military history, and considered the greatest military commander in Russian history, Suvorov has been compared to Napoleon in military generalship. Undefeated, he has been described as the best general Republican France ever fought,[8] and noted as "one of those rare generals who were consistently successful despite suffering from considerable disadvantages."[9] Suvorov was also admired by his soldiers throughout his whole military life, and was respected for his honest service and truthfulness.[10]

|

Main article: House of Suvorov |

Alexander Suvorov was born into a noble family originating from Novgorod at the Moscow mansion in Arbat, given as dowry from his maternal grandfather, Fedosey Manukov [ru]. His father, Vasily Ivanovich Suvorov [ru], was a general-in-chief and a senator in the Governing Senate, and was credited with translating Vauban's works into Russian.[11] His mother, Avdotya Fedoseyevna (née Manukova), was the daughter of judge Fedosey Manukov, and was an ethnic Russian.[12] According to a family legend his paternal ancestor named Suvor[13] had emigrated from Karelia, at the time ruled by the Swedish Empire, with his family in 1622 and enlisted at the Russian service to serve Tsar Michael Feodorovich (his descendants became Suvorovs).[14][11] Suvorov himself narrated for the record the historical account of his family to his aide, colonel Anthing, telling particularly that his Swedish-born ancestor was of noble descent, having engaged under the Russian banner in the wars against the Tatars and Poles. These exploits were rewarded by Tsars with lands and peasants.[15] This version, however, was questioned recently by prominent Russian linguists, professors Nikolay Baskakov and Alexandra Superanskaya [ru], who pointed out that the word Suvorov more likely comes from the ancient Russian male name Suvor based on the adjective suvory, an equivalent of surovy, which means "severe" in Russian. Baskakov also pointed to the fact that the Suvorovs' family coat of arms lacks any Swedish symbols, implying its Russian origins.[16] Among the first of those who pointed to the Russian origin of the name were Empress Catherine II, who noted in a letter to Johann von Zimmerman in 1790: "It is beyond doubt that the name of the Suvorovs has long been noble, is Russian from time immemorial and resides in Russia", and Count Semyon Vorontsov in 1811, a person familiar with the Suvorovs.[17] Their views were supported by later historians: it was estimated that by 1699 there were at least 19 Russian landlord families of the same name in Russia, not counting their namesakes of lower status, and they all could not descend from a single foreigner who arrived only in 1622.[17] Moreover, genealogy studies indicated a Russian landowner named Suvor mentioned under the year 1498, whereas documents of the 16th century mention Vasily and Savely Suvorovs, with the last of them being a proven ancestor of General Alexander Suvorov.[17] The Swedish version of Suvorov's genealogy had been debunked in the Genealogical collection of Russian noble families by V. Rummel and V. Golubtsov (1887) tracing Suvorov's ancestors from the 17th-century Tver gentry.[18] In 1756 Alexander Suvorov's first cousin, Sergey Ivanovich Suvorov, in his statement of background (skazka) for his son said that he did not have any proof of nobility; he started his genealogy from his great-grandfather, Grigory Ivanovich Suvorov, who served as a dvorovy boyar scion at Kashin.[18]

As a boy, Suvorov was a sickly child and his father assumed he would work in civil service as an adult. However, he proved to be an excellent learner, avidly studying mathematics, literature, philosophy, and geography, learning to read French, German, Polish, and Italian, and with his father's vast library devoted himself to intense study of military history, strategy, tactics, and several military authors including Plutarch, Quintus Curtius, Cornelius Nepos, Julius Caesar, and Charles XII. This also helped him develop a good understanding of engineering, siege warfare, artillery, and fortification.[19] His father, however, insisted that he was unfit for military affairs. However, when Alexander was young, General Gannibal asked to speak to the child, and was so impressed with the boy that he persuaded the father to allow him to pursue the career of his choice.[11]

|

Main articles: Seven Years' War, Third Silesian War, and Pomeranian War |

Suvorov entered the military in 1745 and served in the Semyonovsky Lifeguard Regiment for nine years.[20] During this period he continued his studies attending classes at Cadet Corps of Land Forces.[21] He spent most of his time in the barracks: the troops loved him, though everyone considered him eccentric.[22] Besides, he was sent with diplomatic dispatches to Dresden and Vienna; to carry out these assignments on March 16, 1752, he received a diplomatic courier passport, signed by the Chancellor Count Alexey Bestuzhev-Ryumin.[23] In 1756–58 Alexander next worked on the College of War; from 1758 he was engaged in forming reserve units, and was commandant of Memel.[24] Suvorov gained his first battle experience fighting against the Prussians during the Seven Years' and the Third Silesian wars (1756–1763).[b] His first skirmish occurred on 25 July 1759 under Crossen, when Suvorov with a cavalry squadron attacked and routed Prussian dragoons;—he was serving in General-Major Mikhail Volkonsky's brigade.[25][26] The following month Suvorov participated in the complete victory over Frederick the Great at the battle of Kunersdorf,[27] after which the so-called Miracle of the House of Brandenburg happened.

At the time when Pyotr Semyonovich Saltykov, upon his Kunersdorf victory, remained unmoved and did not even send Cossacks to pursue the fleeing enemy, Suvorov said to William Fermor: "if I were commander-in-chief, I would go to Berlin right now". Fortunately for Frederick, he faced not Suvorov.[28]

Then, Alexander served under the command of General-Major Maxim Berg [ru]. Suvorov successfully defended his positions at Reichenbach, but contrary to his future rules did not pursue the retreating enemy, if the only surviving account of this action is accurate. At the skirmish of Schweidnitz, in a third assault, Suvorov managed to take the hill occupied by the hussar picket; in this clash 60 Cossacks opposed 100 hussars.[29] For another example, in the combat of Landsberg on 15 September 1761, his Cossack-hussar cavalry unit defeated 3 squadrons of the Prussian hussars.[30] On leaving the Friedberg Forest, he hit General Platen's side units and took many prisoners.[29] He also fought minor battles at Bunzelwitz, Birstein, Weisentine,[c] Költsch, and seized the small fortified town of Golnau.[31] After repeatedly distinguishing himself in battle Suvorov will become a colonel in 1762, aged around 33.[32] Soon afterwards, following the capture of Golnau, he was given temporary command of the Tver Dragoon Regiment [ru] until the regimental commander recovered. Prussian observation detachments had spread far from Kolberg; Berg moved there in two columns, the left he led himself, and the right, which consisted of three Hussar, two Cossack, and Tver Dragoon regiments, he entrusted to Suvorov. In the village of Naugard[d] the Prussians positioned themselves with 2 battalions of infantry and a weak dragoon regiment. Forming his unit in two lines, Suvorov began the attack. He felled the dragoons, struck one of the battalions, killed many on the spot and took at least a hundred prisoners. At Stargard, Suvorov attacked the rearguard of Platen, during which Suvorov cut into the enemy cavalry and infantry, during which it was reported that "many were taken and beaten from the enemy".[33] Suvorov managed to avoid heavy losses.[31] All the battles described took place at the same time as the siege of Kolberg (1761) in Pomerania.

It is stated that Suvorov visited Prussian Masonic lodge. But it is doubtful that he himself was ever a Freemason.[34][35] Just before his career in 1761, he took part in the raid on Berlin by Zakhar Chernyshev's forces (one year after the Kunersdorf). Suvorov took in a young boy, took care of him during the whole campaign, and on arrival at the quarters sent to the widow, the boy's mother, a letter reading:[36]

"Dear mother, your little son is safe with me. If you want to leave him with me, he will not lack anything and I will take care of him as if he were my own son. If you wish to keep him with you, you can take him from here or write me where to send him."

|

Main article: Bar Confederation |

Suvorov next served in Poland during the Confederation of Bar. Leading a unit of the army of Ivan Ivanovich Weymarn [ru], he dispersed the Polish forces under Pułaski at Orzechowo, captured Kraków (1768), overthrew the Poles of Moszyński near Nawodzice in the spring of 1770, before defeating Moszyński's Polish troops at Opatów in July.[37] The following year Alexander Suvorov won a small combat with Charles Dumouriez's army at Lanckorona, but he failed in the storming of the Lanckorona Castle, being injured here; and then on 20 May 1771, he unsuccessfully stormed the mountain near Tyniec Abbey, which included a strong redoubt enclosed by a palisade, trous de loup,[38] and strengthened with two guns.[39] The Russians under Suvorov and Lieutenant Colonel Shepelev captured the fortification twice, but were beaten back. Fearing to lose a lot of troops and time, Suvorov retreated.[38] It were among the few tactical setbacks in his career, however, these were not field engagements.

Slightly earlier than at Tyniec, however, Suvorov had won small victories over the Confederates at Rachów and Kraśnik (27 & 28 February 1771), capturing an entire wagon train in the first of these clashes. By a "happy coincidence", Suvorov survived in it. After their failure at the Lanckorona Castle, the Suzdals [ru] restored their reputation in Suvorov's eyes, not only at Kraśnik but also in Rachów. He wrote to Weymarn:[40]

The infantry acted with great subordination, and I made my peace with them.

Follow-up clashes rectify Suvorov's situation: the battle of Lanckorona one day after an incident at Tyniec, where Dumouriez, the future hero of the French Republic, was severely defeated; the combat of Zamość on 22 May 1771;[41] the battle of Stołowicze; and the siege of the Wawel Castle (Kraków Castle), where the French and the szlachta, under the leadership of Brigadier Marquess Gabriel de Claude, made a sortie from the fortifications, and a force of Tyniec moved towards them – the Poles and their French allies were "defeated by brutal shooting and put to flight",[42] paving the way for the first partition of Poland between Austria, Prussia and Russia.[43] Suvorov meanwhile reached the rank of major-general.[32]

|

Main article: Kościuszko Uprising |

More than two years after the signing of the treaty of Iași (Jassy) with the Ottoman Empire, Suvorov was yet again transferred to Poland where he assumed the command of one of the corps and led the victorious battles of Dywin, Kobryń, Krupczyce, and the battle of Brest where he vanquished the forces of the Polish commander Karol Sierakowski [pl]; afterwards, Suvorov won the battle at Kobyłka. The cavalry attacks at Brest and Kobyłka resemble of Suvorov's offence at Lanckorona 22 years earlier, which ended in the defeat of Dumouriez. The battle showed that there was stability in his tactical rules, and he did not act on momentary impulse.[44]

Suvorov was praised and exalted, anecdotes were told about him, his letters were quoted. It became known that he wrote a letter to Platon Zubov, in which, congratulating Zubov "with local victories," he proceeded: "I recommend to your favour my brothers and children, squires of the Great Catherine, who is so illustrious thanks to them". Suvorov sent to his daughter poems, where he described his working life:[45]

The heavens have given us

Twenty-four hours.

I do not indulge my fate,

But sacrifice it to my Monarch,

And to end [die] suddenly,

I sleep and eat when at leisure.

Hello, Natasha [ru] and her household.

On November 4, 1794, Suvorov's forces stormed Warsaw, held by Józef Zajączek's troops, and captured Praga, one of its boroughs (a suburb or the so-called faubourg). The massacre of 12,000[46][e] civilians in Praga broke the spirits of the defenders and soon put an end to the Kościuszko Uprising. During the event, Russian forces looted and burned the entire borough. This carnage was committed by the troops in revenge for the slaughter of the Russian garrison in Warsaw during the Warsaw Uprising in April 1794, when up to 4,000 Russian soldiers died.[48] According to some sources[49] the massacre was the deed of Cossacks who were semi-independent and were not directly subordinate to Suvorov. Suvorov supposedly tried to stop the massacre and even went to the extent of ordering the destruction of the bridge to Warsaw over the Vistula River[50] with the purpose of preventing the spread of violence to Warsaw from its suburb. Other historians dispute this,[51] but most sources make no reference to Suvorov either deliberately encouraging or attempting to prevent the massacre.[52][53][54] "I have shed rivers of blood," the troubled Suvorov confessed, "and this horrifies me".[19] A total of 11,000 to 13,000 Poles were taken prisoner (approximately 450 officers), including captured with weapons, unarmed and wounded. Of the men taken alive and wounded, more than 6,000 were sent home; up to 4,000 were sent to Kiev, – from the regular army, without the scythemen, who were set at liberty with other non-military men.[46]

Many writers call the storming of Praga a simple slaughterhouse. As historian Alexander Petrushevsky notes, Suvorov's dispositions of the troops were characterised by remarkable thoroughness; such was that of Praga according to Petrushevsky. "It is homogeneous with the Izmailian at its core and identical to it in many basic details. Both show a remarkable military calculation, which includes not only figures, but knowledge of the enemy's character, properties and general strength, a correct estimation of their own resources, moral and material, and a choice of means based on these data. But even more than the plan (the storming programme), what is striking is its execution, in which some features of the plan turned out to be additional steps to the Russian victory. Only troops who are perfectly trained and between whom and their leader there is complete harmony can act in this way".[46]

Despite early successes on a battlefield, the organizer of the uprising, Tadeusz Kościuszko, was captured by the Don Cossack general Fyodor P. Denisov [ru] at the battle of Maciejowice, where Kościuszko was defeated at the hand of Baron Fersen's larger forces. Suvorov's and other Russians' victories led to the third partition of Poland. He sent a report to his sovereign consisting of only three words:[55]

"Hurrah, Warsaw's ours!" (Ура, Варшава наша!).

Catherine replied in two words:[55]

"Hurrah, Field-Marshal!" (rus. Ура, фельдмаршал! – that is, awarding him this rank).

The newly appointed field marshal remained in Poland until 1795, when he returned to Saint Petersburg. But his sovereign and friend Catherine died in 1796, and her son and successor Paul I dismissed the veteran in disgrace.[32]

|

Main article: Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774 |

The Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774 saw his first successful campaigns against the Turks in 1773–1774, and particularly in the battle of Kozludža (1774); Suvorov laid the foundations of his reputation there.[32] During the same conflict, the Imperial Russian Navy triumphed over the Ottoman Navy at the battle of Cheshme, and Peter (Pyotr) Rumyantsev, likewise one of the most capable Russian commanders of the era as per statistician Gaston Bodart and historian K. Osipov [ru], routed the Ottomans at the battle of Kagul. Petrushevsky states the following: "The battles of Larga, Chesma, and Kagul were balm for the Russian heart of Suvorov, but at the same time a vexation stirred up in him from the fact that he had not participated there. While in Poland, Suvorov's displeasure, inflated by his self-love and unsatisfied thirst for activity, was fed by news from the Turkish theatre of war. There was (or he thought there was) what he wanted, that "comfort" about which he wrote to Yakov Bulgakov in January 1771. Especially strong was to ignite in Suvorov is the desire to go to the main army after its glorious deeds of 1770". It was then that he had already started pushing for a transfer from Poland to Turkey.[56]

His later earned victories against the Ottomans bolstered the morale of his soldiers who were usually outnumbered, such as the stormings of Turtukaya on 21 May–28 June 1773 and the repelling of the assault on Hirsovo fortress with a subsequent counterattack on 14 September that year.[57] In Suvorov's first reconnaissance to Turtukaya the troops pulled up to the tract of Oltenița, not far from the Danube, waiting for dawn. Suvorov stayed at the outposts, wrapped himself in a cloak and went to bed not far from the Danube shore. It was not yet daybreak when he heard loud shouts: "alla, alla"; jumping to his feet, he saw several Turkish horsemen, who with raised sabres were rushing towards him. He had barely time to jump on his horse and gallop away. Carabiniers were immediately sent to assist the attacked Cossacks, and those first-mentioned attacked the Turks in the flank, while they, having struck down the Cossacks, carried on to the heights. The Turks were repulsed, throwing themselves to the ships and hurriedly departed from the shore; there were only 900 of them, of whom 85 were killed, more were sunk; several men were taken prisoners, including the chief of the detachment. According to the testimony of the prisoners Suvorov managed to find out how many men were in the Turtukaya stronghold,[58] and following its capture, even before sunrise, Suvorov wrote in pencil on a small piece of paper and sent to Lieutenant-General Count Ivan Saltykov, in whose division he served, the following short report: "Your Excellency, we have won; thank God, thank you". Suvorov also sent another report to the Commander-in-Chief Rumyantsev, consisting of couplets:[59][60]

Glory to God, glory to you,

Turtukaya is taken and I am there too.

The war ended with the treaty of Küçük Kaynarca.

Suvorov's astuteness in war was uncanny and he also proved a self-willed subordinate who acted upon his own initiative. Rumyantsev's putting Suvorov on trial for his arbitrary reconnaissance of Turtukaya belongs to the realm of pure fiction. Rumyantsev was not dissatisfied with Suvorov, but with Ivan Saltykov.[61] There was inactivity in Wallachia after Suvorov's initial capture of Turtukaya; Saltykov did not take advantage of the successful Turtukaya engagement despite the insistence of Rumyantsev; and Ottoman communications on the Danube became unimpeded. Lieutenant-General Mikhail Kamensky, with whose help Suvorov defeated the Turks at Kozludzha, not liking Suvorov, at the same time teased Ivan Saltykov with the mention of Alexander Vasilyevich. In one "decent, but rather unpleasant" letter to Saltykov, he amuses himself about the second Turtukaya victory of Suvorov and the inaction of Saltykov himself.[62] Plus, a little earlier several reconnaissances had been made from Saltykov's division and one of them very unsuccessful. Colonel Prince Repnin was taken prisoner with 3 staff officers, more than 200 Russians were killed and missing, 2 ships, and 2 cannons were recaptured.[61]

|

Main article: Russo-Turkish War of 1787–1792 |

From 1787 to 1791, under the overall command of Grigory Alexandrovich Potemkin, he again fought the Turks during the Russo-Turkish War of 1787–1792 and won many victories; he was wounded twice at the hard-won Kinburn engagement (1787) and saved only thanks to the intervention of the grenadier Stepan Novikov. Novikov heard the call of his chief, threw himself at the Turks; he stabbed one, shot another and turned to the third, but that one fled, and with him the rest. The retreating Russian grenadiers noticed Suvorov and shouted: "Brothers, the general stayed in front", – rushed again upon the Ottomans. The fight resumed, and the bewildered Turkish soldiers began again to rapidly lose one trench after another.[63] Suvorov suffered greatly from grievous wounds and huge loss of blood; although he kept on his feet, he often fainted, and this went on for a month.[64]

Suvorov was also soon involved in the costly siege of Ochakov (Özi). Energetic and courageous as usual, Alexander Suvorov proposed to take the fortress by storm, but Potemkin was cautious. "That's not how we beat the Poles and the Turks," Suvorov said in a close group of people; "one look will not take the fortress. If you had listened to me, Ochakov would have been in our hands long ago".[65] The siege that took place was supported by a blockade of the Black Sea flotilla of Charles Henri de Nassau-Siegen under John Paul Jones, a renowned fighter for American independence. After a fierce naval combat, the Russian rowing vessels surrounded the flagship and took it; only Kapudan-ı Derya Hasan Pasha managed to escape.[66] However, when great damage was done to the Ottoman fortress plus fleet, "as if inviting" the besiegers to storm, Potemkin still continued the siege, which Rumyantsev wryly called the siege of Troy, and Suvorov described in couplet that he was:

Sitting on a stone so cold,

Watching Ochakov as of old.[f]

The mortality rate was extreme, from one cold 30–40 people a day: the soldiers were stiff in their dugouts, suffering terrible want of essentials, and so were the horses. During Potemkin's visit to the camp, the soldiers took the courage to personally ask him to storm, but this did not work. At last there was a deafening murmur among the whole army. Only having reached such a hopeless situation Potemkin decided to storm, setting it for 17 December,[68][69] in which Suvorov did not participate due to a bullet wound that penetrated his neck and stopped at the back of his head. This happened during a successful Ottoman sortie from the fortress.[g][70]

In 1789, after the joint Russian and Habsburg victorious battle of Focșani, he and the talented Austro-Bavarian general Josias of Coburg fought most decisive victories in their career. First at the battle of Rymnik, where, despite the vast inferiority in numbers (a Russian–Austrian force of 25,000 against 100,000 Turks), Suvorov persuaded the Austrian commander to attack;[71] with the bold flanking maneuver of Suvorov and the resilience of the Austrians, together they routed the Ottoman army within a few hours, losing only 500 men in the process. Suvorov earned the nickname "General Forward" in the ranks of the Austrian corps for the latter victory; the word combination came to his attention and gave him sincere pleasure, as he later recalled this martial assessment of his person, smugly grinning.[72] Suvorov's 11th Fanagoriysky Grenadier Regiment was formed from soldiers who took part at Rymnik. Catherine the Great, in turn, made Suvorov a count with the name Rymniksky (or Rimniksky[73]) as a victory title in addition to his own name, and the Emperor Joseph II made him a count of the Holy Roman Empire.[32]

The second one came at the storming of Izmail in Bessarabia on 22 December 1790. On 20 December Suvorov convened a military council. Petrushevsky writes as follows: "Suvorov had nothing to consult about, but by doing so, he acted on the basis of the law and used this means to communicate his decision to others, to make his view their view, his conviction – their conviction." Petrushevsky further observes: "This is very difficult for ordinary commanders who do not tower over their subordinates in anything other than their position; but easy for such as Suvorov. There is no need for ranting, or intricately woven evidence; it is the winning authority that persuades, the unbending will that fascinates". Suvorov spoke a little in council and nevertheless brought everyone into raptures, he enthralled the very people who a few days ago considered the same assault unrealisable. The youngest of those present, Brigadier Platov, said the word assault, and the decision to assault was taken by all 13 persons without exception. The council determined:[74]

"approaching Izmail, according to the disposition to storm it without delay, in order to give the enemy no time for further strengthening, and therefore there is no need for reference to his lordship the commander-in-chief [Grigory Potemkin]. Serasker's request is to be refused. The siege must not be turned into a blockade. Retreat is reprehensible to Her Imperial Majesty's victorious troops. By virtue of chapter fourteen of the military regulations [ru]."

Turkish forces inside the fortress had the orders to stand their ground to the end and haughtily declined the Russian ultimatum. Despite the fact that Mehmed Pasha was a resolute and firm commander, and inflicted serious losses on the Russians, his army was destroyed. Their defeat was seen as a major catastrophe in the Ottoman Empire, and in Russian military history there has never been a similar instantaneous storming of a fortress in terms of numbers and casualties as that of Izmail, much less without a proper siege. An unofficial Russian national anthem in the late 18th and early 19th centuries "Grom pobedy, razdavaysya!" ("Let the Thunder of Victory Rumble!"; by Gavrila Derzhavin and Józef Kozłowski) immortalized Suvorov's victory and 24 December is today commemorated as a Day of Military Honour in Russia. In this war Fyodor Ushakov also won many famous naval victories, as in the battle of Tendra, which deprived the Ottomans of Izmail's support from the Danube. Suvorov announced the capture of Ismail in 1791 to the Empress Catherine in a doggerel couplet.[75]

The war ended with the treaty of Jassy.

From 1774 to 1797, Suvorov stayed and served in Russia itself, that is, in Transvolga or "Zavolzhye", in Astrakhan, Kremenchug, the Russian capital Saint Petersburg; in Crimea, or, more accurately, Little Tartary (Kuban which is in the North Caucasus, and Kherson); in the recently former Poland (Tulchin, Kobrin); and in the Vyborg Governorate, on the border with Swedish Finland.

|

Main article: Pugachev's Rebellion |

In 1774, Suvorov was dispatched to suppress Pugachev's Rebellion, whose leader Yemelyan Pugachev claimed to be the assassinated Tsar Peter III. Count Pyotr Panin, appointed for operations against Pugachev, asked to appoint a general to assist him, who could replace him in case of illness or death. On the very day of the news' arrival of Pugachev's passage to the right bank of the Volga, Rumyantsev sent orders – to send Suvorov to Moscow as soon as possible. Suvorov, who was in Moldavia, immediately rushed out at full speed, met in Moscow with his wife and father. On the order left by Panin, in one caftan and without luggage, raced to the village of Ukholovo, between Shatsk and Pereyaslavl Ryazansky. He arrived in Ukholovo on September 3 (NS), just at the time when Panin received notice of Alexander Vasilyevich's appointment. Panin gave him broad powers and ordered the military and civil authorities – to execute all Suvorov's orders.[76]

After receiving instructions, Suvorov the same day set out on the road, in the direction of Arzamas and Penza to Saratov, with a small escort of 50 men. Panin reported to the Empress on the rapid performance of his new subordinate, which "promised in the circumstances of the time a lot of good ahead and therefore worthy of attention". Thanking him for such zeal and speed, the Empress granted him 2,000 chervonets to equip the crew. Reaching Saratov, Suvorov learned that tireless Ivan Mikhelson, who "like a shadow" followed everywhere after Pugachev and repeatedly defeated him, again defeated him badly. Strengthening his detachment here, Suvorov hurried to Tsaritsyn, but a lot of horses went to Pugachev, there was a lack of them, and Suvorov was forced to continue the journey by water. Defeated by Mikhelson, Pugachev slipped away; having somehow crossed the Volga with a small number of his loyalists, he disappeared into the vast steppe. Hasty arrival of Suvorov in Tsaritsyn drew the attention of the Empress, who announced her pleasure to Count Panin. But Suvorov was still essentially late. However, Suvorov did not stop it, he assigned to his detachment 2 squadrons, 2 Cossack sotnias, using horses captured by Mikhelson put on horseback 300 infantrymen, seized 2 light guns, and after spending less than a day on it all, crossed the Volga. Apparently, for reconnaissance on the rebels, he first moved upriver, came to a large village, which kept the Pugachev side, took 50 oxen, and then seeing that around the quiet, turned to the steppe. This vast steppe, which stretched for several hundred km., desolate, woodless, homeless, was a "dead desert, where even without the enemy's weapons was threatened with death". Suvorov had very little bread; he ordered to kill, salt and bake on fire some of the taken cattle and use the slices of meat for people instead of bread, as he did in the last campaign of the Seven Years' War. Thus secured for some time, Suvorov's detachment went deeper into the steppe. "They followed the sun by day and the stars by night; there were no roads, they followed the traces and moved as fast as they could, not paying attention to any atmospheric changes, because there was no place to hide from them". In different places Suvorov was overtaken and joined by several detachments, who went before him from Tsaritsyn; September 23 (NS), he came to the Maly Uzen River, divided his squad into four parts and went to the Bolshoy Uzen in different directions. Soon they stumbled on Pugachev's trail; they found out that Pugachev was here in the morning, that his men, seeing an unstoppable pursuit, lost faith in the success of their cause, revolted, tied Pugachev and took him to Yaitsk, to extradite the leader to save themselves. And indeed Pugachev was arrested, as it turned out later, at this time, some 53 km (33 mi) from Suvorov.[77] Suvorov arrived at the scene only in time to conduct the first interrogation of the rebel leader, but Suvorov missed the chance to defeat him in battle, who had been betrayed by his fellow Cossacks and was eventually beheaded in Moscow.[32]

|

Main article: Kuban Nogai Uprising |

As a result of the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774, the Crimean Khanate became independent of the Ottomans, but in fact became a Russian protectorate (1774 to 1783). The Russian-imposed Şahin Giray proved unpopular. The Kuban Nogais remained hostile to the Russian government.[78] From the end of January 1777, Suvorov set about building new fortifications at Kuban, despite the severe cold and predator raids, suggesting that the entire cordon should be shortened, and that it should be connected to the Azov-Mozdok fortified line [ru]. There were only about 12,000 men under Suvorov's command. He explored the region, more than 30 fortifications were built, and the order of service at the cordon was changed. Attacks from across the Kuban ceased; Tatars, guarded against the unrest of Turkish Zakuban [ru] emissaries and from the raids of predators, were pacified, and began to make sure that the Russians really had good intentions towards them. But the peace was short-lived, however. "Intelligent Rumyantsev could not fail to appreciate the fruitful activities of Suvorov in Kuban" and spoke of him with pleasure and praise.[79]

By 1781, the situation in the Crimean Khanate, especially in the North-West Caucasus, had "heated up to the limit". Dissatisfaction with the Khan and the withdrawal of Russian troops led to an uprising of the Kuban Nogais at the beginning of the year. By July 1782, the uprising had spread to Crimea. In September–October 1782, Suvorov was engaged in "restoring order" on the territory of N.-W. Caucasus. The first insurrection was suppressed by the force of returning Russian troops directly by Alexander Suvorov and Anton de Balmen at the end of 1782 (Balmen put down a rebellion on the Crimean Peninsula territory). In 1783, Suvorov with complete surprise for the rebels crossed the Kuban River and in the battle of the Laba on 1 October (near Kermenchik tract) decisively quelled the second Nogai uprising, which, in turn, was triggered by Catherine's manifesto, declaring Crimea, Taman, and Kuban as Russian possessions.[78] At the Laba, Nogai losses amounted to 4,000.[80]

|

Main article: Emigration of Christians from the Crimea (1778) |

On behalf of Empress Catherine II, Suvorov participated in an incident – the forced resettlement of Christians from Crimea.[19] The possession of Crimea did not seem secure for Russia at that time. Russia had to extract all it could from Crimea, and this was achieved by resettling Christians, mainly of Greek and Armenian nationalities, from Crimea: they had industry, horticulture and agriculture, which constituted a significant part of the Crimean Khan's income. The fact that the Crimean Christians were burdened "to the last degree" by the Khan's extortions and, therefore, the tax exemption granted to them in the new place should have inclined them in favor of the measure conceived by the Russian government, was in favor of the feasibility of resettlement. Thus the matter was resolved and Suvorov was entrusted with its execution.[81] In the second half of September 1778 the resettlement ended. More than 31,000 souls were evicted; the Greeks were mostly settled between the rivers Berda [uk] and Kalmius, along the river Solyonaya [uk] and all the way to Azov; the Armenians near Rostov and generally on the Don. Rumyantsev reported to the Empress that "the withdrawal of the Christians can be regarded as a conquest of a noble province". 130,000 rubles were spent for transportation and food. Petrushevsky suggests that food itself cost very cheap, because Suvorov bought from the same Christians 50,000 quarters of bread, which, coming locally to the shops, cost half as much as delivered from Russia, what resulted in savings of 100,000 rubles. "Suvorov's orders were distinguished by remarkable and calculated prudence, he had put his heart into this business". More than half a year later, when the case was almost submitted to the archives, Suvorov still felt as if he had a moral obligation towards the settlers and wrote to Potemkin:[82]

"The Crimean settlers suffer many shortcomings in their present state; look upon them with a merciful eye, who have sacrificed so much to the throne; relish their bitter remembrance."

After Suvorov organized the resettlement of Armenian migrants displaced from Crimea, Catherine gave them permission to establish a new city, named Nor Nakhichevan by the Armenians. In addition, Alexander Suvorov would later found the city of Tiraspol (1792), now the capital of Transnistria.

In 1778 Alexander as well prevented a Turkish landing on the Crimean Peninsula, thwarting another Russo-Turkish war.[19] In 1780 he became a lieutenant-general and in 1783 – General of the Infantry, upon completion of his tour of duty in the Caucasus and Crimea.[32]

Going to Kherson (1792), Suvorov received quite a detailed instruction. He was entrusted with command over the troops in the Yekaterinoslav Governorate, Taurida Oblast and the territory newly annexed from Ottoman Turkey, with the responsibility to manage the fortification works there. Black Sea Fleet was under the command of Vice-Admiral Nikolay Mordvinov, and a rowing fleet under the command of General-Major Osip Deribas, who was dependent on Suvorov only for troops in the fleet. Suvorov was ordered to inspect the troops to ascertain their condition and replenish what was missing, to survey the coast and borders, and submit his opinion on bringing them to safety from accidental attack; he was also allowed to change the disposition of the troops without giving any reason for neighbors to think that the Russians were anxious; – finally, he was ordered to collect and submit notifications from abroad.[83]

Engineering occupied the most prominent place in Suvorov's activities in the south, as well as in Finland. The plans signed by him were preserved: the project of the Phanagoria fortress, three projects of fortifications of the Kinburn Spit and the Dnieper–Bug estuary, the plan of the Kinburn Fortress [ru], the main logistics center of Tiraspol, the fort of Hacıdere (Ovidiopol) on the Dnieper–Bug estuary, Khadjibey (Odessa) and Sevastopol (Akhtiar) fortifications. Some of these were built during his time there and have progressed considerably, others had only just begun; there were also fortifications remained in the project due to short time and lack of money. At Sevastopol four forts were started, including 2 casemated; in Khadjibey was placed a military harbor with a merchant pier, according to François Sainte de Wollant's plans, under the direct supervision of Deribas and supreme surveillance of Suvorov.[84]

In Tulchin he contributed to the training of troops (1796). On arriving in Tulchin, Suvorov first of all paid attention to the welfare of the soldiers. There were "huge numbers" dying, as in epidemic times, especially at work in the port of Odessa, where the annual percentage of deaths reached up to 1/4 of the entire staff of the troops, and one separate team died out almost entirely. The reason: "many generals were suppliers to the troops"; the builder of Odessa Deribas capitalised "terribly" on this. Against all the "evils" detected, Suvorov took immediate measures, akin to those of the previous ones, and watched their execution vigilantly. Barely two months have passed before the death rate in Odessa fell fourfold, and in some other places the percentage of deaths was closer to normal, and in August it was below normal.[85]

A feast was held in Russia to commemorate glorious military exploits, especially the storming of Izmail. A few days before the feast, May 6 (NS), 1791, Suvorov received from Potemkin command of the Empress – to go around Finland to the Swedish border, to design a border fortifications. Suvorov went willingly, "just to get rid of his inactivity"; the region was familiar to him, as 17 years ago he had already traveled around the Swedish border, and although the present task seemed more difficult, but with his usual energy and diligence, Suvorov completed it in less than 4 weeks.[86] The Empress treated with full approval of Suvorov's construction works.[87]

During the harsh Finnish spring, he traveled in sledges in the wild backwoods of the Russian–Swedish border, enduring hardships that "a military man of high position does not know even in wartime". Repeated the same old thing: Suvorov had already traveled in winter inclement weather, riding on a Cossack horse, without luggage, to Izmail.[86]

Suvorov, besides building and repairing fortresses, had troops and a flotilla on his hands. The greater part of the rowing flotilla was in the skerries, the smaller on Lake Saimaa. At first the flotilla was commanded by Prince Nassau-Siegen, but in the summer of 1791, he absented himself from Catherine on the Rhine to offer his services to the French princes for the war against the Republicans. The flotilla was numbering upwards of 125 vessels of various names and sizes, with 850 guns; it was under the command of Counter-Admiral Marquess de Traversay and General-Major Hermann, subordinates to Suvorov. He was responsible for manning ships, for training people, for conducting naval exercises and maneuvers. Suvorov was never a nominal chief; he endeavoured to familiarise himself, as much as possible, with marine speciality. Some practical information he had acquired earlier, in the Dnieper–Bug estuary, where a flotilla was also under his command, and continued in Finland to look into naval affairs. On his first trip here he took private lessons, about which he wrote to Military Secretary Turchaninov [ru]; later, according to some reports, he jokingly asked to test himself in naval knowledge and passed the exam "quite satisfactorily".[88]

Suvorov lived in different places in Finland, depending on the need: in Vyborg, Kymmenegård [fi], Ruotsinsalmi. In Kymmenegård he left a memory of his concern for the Orthodox Church: he sent a church choir director from St. Petersburg to train local choristers, bought different church things for several hundred rubles. Here he formed a circle of acquaintances, free from service time spent fun; Suvorov often danced, and in a letter to Dmitry Khvostov bragged that once he "contradanced for three hours straight".[89]

Suvorov remained a close confidant of Catherine, but he had a negative relationship with her son and heir apparent Paul. He even his own regiment of Russian soldiers whom he dressed up in Prussian-style uniforms and paraded around. Suvorov was strongly opposed to these uniforms and had fought hard for Catherine to get rid of similar uniforms that were used by Russians up until 1784.[32]

When Catherine died of a stroke in 1796, Paul I was crowned Emperor and brought back these outdated uniforms.[19] It is considered that in the same year the Golden Age [ru] of Russian nobility and of the Russian Empire came to an end, along with Catherine the Great.[90] Suvorov was not happy with Paul's reforms and disregarded his orders to train new soldiers in this Prussian manner, which he considered cruel and useless.[19] Paul was infuriated and dismissed Suvorov, exiling him to his estate Konchanskoye [ru] near Borovichi and kept under surveillance. His correspondence with his wife, who had remained at Moscow for his marriage relations had not been happy, was also tampered with. It is recorded that on Sundays he tolled the bell for church and sang among the rustics in the village choir. On week days he worked among them in a smock-frock.[32]

|

Main articles: French Revolutionary Wars and War of the Second Coalition |

|

Main article: Italian and Swiss expedition |

In February 1799, Paul I, worried about the victories of France in Europe during the French Revolutionary Wars and at the insistence of the coalition leaders, was forced to reinstate Suvorov as field marshal.[32] Alexander Suvorov was given command of the Austro-Russian army and sent to drive France's forces out of Italy. For subordination of the Austrian soldiers to a general of foreign service, it was deemed necessary to place him a step above the most senior Austrian generals of the army of Italy, also granting the field-marshal of the HRE.[91]

Suvorov and Napoleon never met in battle because Napoleon was campaigning in Egypt and Syria at the time. However, in 1799, Suvorov erased practically all of the gains Napoleon had made for France in northern Italy during 1796 and 1797, defeating some of the republic's top generals: Moreau and Schérer at the Adda River (Lecco, Vaprio d'Adda, Cassano d'Adda, Verderio Superiore), again Moreau at San Giuliano (Spinetta Marengo[h]), MacDonald near the rivers of Tidone, Trebbia, Nure at the Trebbia battle, and Joubert along with Moreau at Novi;[19] but the Russians lost the battle of Bassignana. All the major battles (Adda, Trebbia, Novi) are of the most decisive nature.[92] Besides, the following Italian fortresses fell before Suvorov: Brescia (21 April); Peschiera del Garda, Tortona, Pizzighettone (April); Alessandria, Mantua (July). Suvorov captured Milan and Turin, as well as citadels of these cities, and became a hero to those who opposed the French Revolution. Allied forces also took the towns of Parma and Modena, the capitals of the Duchies of Parma–Piacenza and Modena–Reggio respectively. The British drawn many caricatures dedicated to Suvorov's expedition.[i]

The French client states Cisalpine Republic and Piedmontese Republic collapsed in the face of Suvorov's onset. Admiral Ushakov, sent to the Mediterranean for support to Suvorov, in 1799 completed the five-month siege of Corfu (1798–1799) and put an end to the French occupation of the Ionian Islands in Greece. On receiving news of the capture of Corfu, Suvorov exclaimed:[93]

Our Great Peter is alive! What he, after defeating the Swedish fleet near Åland in 1714, said, namely that nature has produced only one Russia: she has no rival, — we see it now. Hooray! To the Russian fleet!.. I now say to myself: why wasn't I at least a midshipman at Corfu?

The sister republic in the south, the Parthenopean, also fell before the British Royal Navy, Ushakov's naval squadron, and the local rebels, since Jacques MacDonald at the head of the Army of Naples was forced to abandon southern Italy to meet Suvorov at the Trebbia, leaving only weak garrisons in the Neapolitan lands. MacDonald attacked Ott's small force, whereupon Suvorov quickly concentrated most of his army against MacDonald and threw his men into the fray immediately after a hard march. This confrontation near the Trebbia proved to be the toughest French defeat of Suvorov's Italian campaign: by the end of the retreat, MacDonald had barely 10,000 to 12,000[j] men left out of an army of 35,000.[95] The battle of Novi, on the other hand, is the most difficult victory in Suvorov's career, largely because the French had strong defensive positions and the Allies could not fully deploy their superior cavalry as a consequence;[96] however, the Russo-Austrian victory turned into a complete rout for the French army. Its troops lost 16,000 of their comrades-in-arms (in total) and were driven from Italy, save for a handful in the Maritime Alps and around Genoa.[97] But the Hofkriegsrat did not choose to take advantage, and sent Suvorov with his Austrian and Russian forces to Switzerland. Suvorov himself gained the title of "Prince of the House of Savoy" and the rank of grand marshal of the Piedmont troops from the King of Sardinia,[98] and after the Trebbian battle – the title of "Prince of Italy" (or Knyaz Italiysky).[99]

Like Gustavus Adolphus, Turenne, Frederick II the Great, Alexander the Great, Hannibal, and Caesar, in military affairs Alexander Vasilyevich was not vulnerable at any point, rushing with speed to the most important places, and carefully observed the principle of force concentration all his life:[100] at San Giuliano Vecchio (1st Marengo), for example, his troops gathered more than double superiority,[101] and at Novi not so considerable, but at least reaching about 38 per cent, which was still offset by the French army's favourable position.[102] The combat of Lecco, fought as a diversionary maneuver, brought virtually no advantage to either side, but at the beginning, before the reinforcements, the Russian troops were far inferior in numbers. At the combat of Vaprio (part of Cassano), passing through a river obstacle, the Coalition eventually managed to concentrate four thousand more troops in practice than the French did, largely also at the expense of the Cossacks; although in the middle of the battle the French had a twofold preponderance in numbers. In the end there were about 11,000 Austrians and Cossacks versus 7,000 French; but French troops began to give up their footholds before the remaining Austrian battalions arrived. Notwithstanding all, the outcome of the combat at Vaprio d'Adda could have been the only outcome: the timely arrival of 3,000 from Sérurier's division, 6,000 from Victor's division (2,000 he could have left at Cassano d'Adda on the way), would be 16,000 French, led by Moreau, against 11,000 of the enemy.[103] At Cassano d'Adda, Suvorov allocated about 13,000 Austrians against approximately 3,000 French from the divisions of Paul Grenier and Claude-Victor (along with reinforcements), who had taken up strong defences behind the stream; but it was the combat of Vaprio that was decisive and pivotal. At Verderio the Sérurier detachment, cut off during the combat at Vaprio d'Adda, was surrounded and pinned down by the river. Thus, with roughly equal strength overall, having a minimum of 65,000 men at his disposal against the 58,000 available for active operations in the field[104] as part of the French Army of Italy, Suvorov was able to use every advantage he had in the theater to win a complete victory at the battle of Cassano.[105] The blame lies with Barthélemy Schérer: he scattered an even cordon along the whole river; on the more important stretch from Lecco to Cassano d'Adda, 42 km (26 mi), there were no more than 12,000; meanwhile Suvorov had 42,000 on the same stretch.[106]

Near the Trebbia, in contrast to the above, MacDonald had one and a half superiority; this circumstance is explained by the fact that Kray, despite the order of Suvorov, did not send him reinforcements, based on the direct command of Holy Roman Emperor Francis II not to separate any forces before the surrender of Mantua. It was too late for the commander-in-chief to find out.[107] At the battle of the Trebbia on the first day at the Tidone River, the French had 19,000 men against his 14–15,000,[108] and were thrown back. By the Trebbia River itself on the second day the forces were equal, and on the third day Suvorov, with some 22,000 men, beat MacDonald's force of 33,000–35,000. Suvorov then rushed into a fighting pursuit, and at the Nure River, similar to Verderio, an entire Auvergne Regiment was captured after a short battle.[109]

Despite the restraining influence of the Hofkriegsrat, Suvorov always held the initiative in his hands when dealing with the enemy. If the French sometimes tried to catch him (e.g., the movements of Moreau and MacDonald to join at Tortona), the Allies concentrated and dealt brutal blows like at the Trebbia. As for Novi, Joubert, advancing from Genoa to Tortona and expecting to catch the Allied Field Army scattered, unexpectedly met Suvorov and his "strike fist" behind Novi Ligure.[110] But perseverance in the battle of Novi came to the point that when the Russian attacks were unsuccessful, Suvorov got off his horse and, rolling on the ground, shouted: "dig a grave for me, I will not survive this day", and then resumed his attacks. Moreau spoke of Suvorov in this way:[111]

"What can you say of a general so resolute to a superhuman degree, and who would perish himself and let his army perish to the last man rather than retreat a single pace."

As a disadvantage to his decisiveness, Field Marshal Suvorov, famous for the storming of Izmail, did not want to storm the citadels of Italian cities, and preferred to resort, in accordance with the situation, to blockade and siege.[112] Nevertheless, during the Italian campaign of 1799 Suvorov's talent expressed itself fully and comprehensively. Nikolay Orlov describes: "When assessing Suvorov's actions, one must always keep in mind the unfavourable situation for the commander, the environment in which he was:—meaning mainly the inconvenience of commanding the Allied troops, originating from the difference in political aspirations of the Allied governments, and the binding influence of the Hofkriegsrat".[113]

The Polish forces had a no small quantity of militias, and the Turks and Tartars were largely "unstable hordes". True, "all these opponents were characterised by fanatical bravery, it was not easy for Suvorov to overcome them; the wars brought Suvorov practice, from which he took out extensive experience, his talent gradually developed and strengthened in this fight, the commander learned the essence, the spirit of war".[114] In 1799, Suvorov's enemies were troops purely regular, crowned with the glory of victories over the German armies (considered themselves the best in Europe), and were led by some of the best generals of the time,[113] including Jean Victor Moreau, "a man in the prime of life" (35), who was generally respected in the army, distinguished by his theoretical knowledge of the art of war and combat experience, affability and high intelligence. "He was not a high-minded genius, but the presence of mind and unwavering equanimity gave him the ability to come out with honour from the most critical circumstances. At any rate, after Bonaparte, he was the best French general of the time" (the talented Lazare Hoche was no longer alive),[115] winning the famous victory at Hohenlinden a year later. The theater of war was not like those steppes, swamps and forests, among which the commander had hitherto fought.[113] In the war with the French Suvorov was not only commander-in-chief, independently acting in the theater of operations, but in addition he was in charge of the allied army – a matter even more difficult for a commander,[113] and in the battles of Cassano and Novi the Austrians formed the bulk of the army, while at Cassano only irregular Cossack troops participated from the Russian side, including the encirclement of the French detachment at Verderio. It should also be noted that Suvorov, being fiery and irritable, was able to restrain himself in many cases.[111]

|

Main article: Suvorov's Swiss campaign |

After the victorious Italian theater, Suvorov planned to march on Paris, but instead was ordered to Switzerland to join up with the Russian forces already there and drive the French out. The Russian army under General Korsakov was defeated by André Masséna at Zürich, and Friedrich von Hotze's Austrian army was defeated by Jean-de-Dieu Soult at the Linth River before Suvorov could reach and unite with them all. "…I have defeated myself Jelačić and Lincken who are now pinned down in Glarus. Marshal Suvorov is surrounded on all sides. He will be the one forced to surrender!"—said Gabriel Jean Joseph Molitor to Franz von Auffenberg and Pyotr Ivanovich Bagration.[116]

Surrounded by Masséna's 77,000 French troops,[117] Suvorov with a force of 18,000 Russian regulars and 5,000 Cossacks, exhausted and short of provisions, led a strategic withdrawal from the Alps while fighting off the French.[19]

Early on in the path, going to join with the not yet defeated Korsakov, he struggled against general Claude Lecourbe and overcame the St. Gotthard and Oberalp (that goes round Oberalpsee) mountain passes. Suvorov's troops beat the French out of Hospental (situated in the Urseren valley), followed by the so-called Teufelsbrücke, or "Devil's Bridge", located in the Schoellenen Gorge, and the Urnerloch rock tunnel. All these interventions were not without great losses for Suvorov; but in his main attack, where he concentrated some 6,700 against 6,000 Frenchmen, he suffered relatively the same casualties as his opponent.[118] However, Suvorov's troops were at their wits' end.

Russian troops of Andrey Grigoryevich Rosenberg crossed the Lukmanier Pass, Austrian troops of Franz Auffenberg overcame the Chrüzli Pass, while Suvorov himself also later traversed more remote passes such as Chinzig and Pragel (Bragell), before climbing the 8,000-foot mountain Rossstock.[119] Marching over rocks had worn out the soldiers' inadequate footwear, of which many were now even deprived, uniforms were often in tatters, rifles and bayonets were rusting from the constant dampness, and the men were starving for lack of adequate supplies,—they were exhausted, surrounded by impassable mountains in freezing cold, and, one way or another, faced a French army far superior in numbers and equipment. Cossack reconnaissance units instead of the Austrians of Lincken found the French there. France's forces, meanwhile, blocked off many important places for troop movements;[120] and on September 29 (18 OS), still uncertain but informed about the fate of Korsakov and Hotze (from the testimony of French prisoners), Suvorov assembled a council of war in the refectory of the Franciscan monastery of Saint Joseph, which decided to pave the way for the army toward Glarus. During the council the Russian commander showed himself extremely resolute not to surrender, blamed the Austrian allies for all the hardships they were forced to suffer, and proposed what appeared to him to be the only possible solution. Suvorov dictated the disposition: in the vanguard appointed to go Auffenberg, who came out on the 29th, and the next day the rest of the troops, except for Rosenberg's corps and Foerster's [ru] division, which remained in the rearguard and must hold the enemy coming out of Schwyz until all the packs had passed over the mountain Bragell. Rosenberg was ordered to hold firm,—to repel the French with all his strength, but not to pursue him beyond Schwyz.[121] Alexander Suvorov's speech was written down from the words of Pyotr Ivanovich Bagration, made a huge impression on everyone who attended[122] (especially angry and menacing looked Derfelden and Bagration[121]):

We are surrounded by mountains… surrounded by a strong enemy, proud of victory… Since the Pruth expedition, under the Sovereign Emperor Peter the Great, Russian troops have never been in such a perilous position…[122] To go back is dishonorable. I have never retreated. Advancing to Schwyz[k] is impossible: Masséna commands more than 60,000 men and our troops do not reach 20,000. We are short of supplies, ammunition and artillery… We cannot expect help from anyone. We are on the edge of the precipice! All we have left is to rely on Almighty God and the courage and spirit of sacrifice of my troops! We are Russians! God is with us![120]

Between 30 September and 1 October 1799, Suvorov's vanguard of 2,100 men, led by Bagration, was able to break through the Klöntal valley,—with Klöntalersee inside,—and reached the goal. It inflicted 1,000 killed or wounded, and another 1,000 captured to a French force of 6,500 men.[8] However, Bagration tried to push further than Glarus, failing to do so: he was finally stopped by Molitor's troops.

When Molitor took up a position at Netstal, he held for a long time, in spite of Bagration's persistent attacks. Finally driven out of Netstal with the loss of a cannon, a banner and 300 prisoners, Molitor retreated to Näfels, on both banks of the river Linth. Here the French took a strong position, where they again repulsed Bagration long and hard. No matter how weakened Bagration's troops were by the previous battles and heavy march through the mountains, they had so far gained superior numbers over Molitor's detachment. Molitor had gone into full retreat, but the long-expected advance troops of Gazan soon came to his aid. The French now received an overwhelming strength and knocked them out of Näfels. Bagration in turn attacked Näfels and drove off the French, who then went on the attack again. Five or six times the village passed from hand to hand, and when last time it was occupied by the Russians, Bagration received orders from Suvorov to withdraw to Netstal, where at that time the rest of Derfelden's troops were already concentrated. It was evening when Bagration came out of Näfels; noticing this, Gazan moved all his forces to the attack and himself led the grenadiers to the bayonets; but this time the French were also repulsed, and Bagration's troops retreated quite calmly to Netstal.[123]

Meanwhile, on the same days, the rearguard of 7,000 men[8][124] out of a total of 14,000, commanded by Andrey Rosenberg, who, according to plan, was assigned the task of deterrence, met with Masséna's forces, which numbered up to 15,000 men[8] out of 24,000 in the Muotatal (Muota valley), formerly Muttental. Suvorov ordered to hold on there at all costs, and the rearguard, suffering 500[124] to 700[125] casualties, routed the French by inflicting them between 2,700[8] and 4,000[126] losses in two days. More than 1,000 prisoners alone were taken, including a general and 15 officers. Suvorov reported to Paul 6,500 French dead, wounded and prisoners of war in two days of fighting: 1,600 – September 30 and 4,500 – October 1.[127] While Suvorov was fighting the French, the short-lived Roman sister republic had also fallen before the troops of the restored Kingdom of Naples.

Despite all the Russian successes on the battlefield, they were not going to win the campaign. Suvorov hoped to make the way for his exhausted, ill-supplied troops over the Swiss passes to the Upper (Alpine) Rhine and arrive at Vorarlberg, where the army, much shattered after a lot of crossing and fighting, almost destitute of horses and artillery, went into winter quarters.[32] When Suvorov battled his way through the snow-capped Alps his army was checked but never defeated. Suvorov refused to call it a retreat and commenced a trek through the deep snows of the Panixer (Ringenkopf) Pass and into the 9,000-foot mountains of the Bündner Oberland, by then deep in snow. Thousands of Russians slipped from the cliffs or succumbed to cold and hunger, eventually escaping encirclement and reached Chur on the Rhine, with the bulk of his army intact at 16,000 men.[128] After the troops reached Chur, they crossed another pass in the form of the St. Luzisteig, and hence left the territory of present-day Switzerland.[119]

For this marvel of strategic retreat, earning him the nickname of the Russian Hannibal, Suvorov became the fourth Generalissimo of Russia on 8 November 1799 (28 OS).[129] Historian Christopher Duffy, on the back cover of his book Eagles Over the Alps: Suvorov in Italy and Switzerland, 1799, called Suvorov's whole Italian and Swiss adventure a kind of Russian "crusade" against the forces of revolution.[130]

Recently, beginning with his involuntary stay in the village of Konchanskoye, Suvorov often felt unwell; when he returned to duty, he seemed to have recovered, but by the end of the Italian campaign again began to grow weak. Before the Swiss campaign, his weakness was so great that he could hardly walk, his eyes began to hurt more often than before; making itself felt the old wounds, especially on his leg, so that not always could put on a boot. The Swiss campaign made him sicker; he began to complain of cold, which had never happened before; the cough, which had become attached to him some months before, did not leave him either, and the wind became particularly sensitive.[131] He was officially promised a military triumph in Russia, but Emperor Paul cancelled the ceremony and recalled the Russian armies from Europe, including the Batavian Republic after the unsuccessful Anglo-Russian invasion of Holland; and ultimately the French would regain all of their conquered possessions on the Italian Peninsula.

The return journey of Suvorov to Russia lasted more than three months.[132]

Suvorov's name, which had grown during the Italian campaign, took on a double luster after the Swiss campaign, and when he retired from the theatre of war and entered Holy Roman Empire (Germany), he became the centre of attention. Travellers, diplomats and soldiers flocked to his destinations, especially on his longer stops in Lindau, Augsburg and Prague. "A general reverence bordering on awe", ladies sought out the honour of kissing his hand, and he did not particularly resist this. Everywhere he was welcomed and seen off, though he avoided it; every social gathering was eager to have him as its guest.[133]

Russian society was proud of its hero and worshipped him enthusiastically. The Emperor Paul was a "true" representative of the national mood; he accompanied all his rescripts with expressions of the most gracious disposition to the Generalissimo, spoke of his unanimity with him, asked advice, and apologised for giving instructions himself. "Forgive me, Prince Alexander Vasilievich," wrote the tsar, "may the Lord God preserve you, and you preserve the Russian soldiers, of whom some were everywhere victorious because they were with you, and others were not victorious because they were not with you". In other rescript it has told:

"…excuse me, that I have taken it upon myself to give you advice; but as I only give it for preservation of my subjects, which have rendered me so much merit under your leadership, I am sure, that you with pleasure will accept it, knowing your affection to me."

In the third:

"I shall be pleased if you will come to me to advice and to love, after you have bring the Russian troops into our borders."

The fourth reads:

"It is not for me, my hero, to reward you, you are above my measures, but for me to feel it and appreciate it in my heart, giving you your due."

The Tsar had extended his courtesy to the point that, in reply to Suvorov's New Year greetings, he asked him to share them with his troops if he, the Tsar, was "worthy of it" and expressed his desire "to be worthy of such an army".[134]

The famous Admiral Lord Nelson, who, according to the Russian ambassador in London, was at that time together with Suvorov the "idol" of the English nation, also sent the Generalissimo an enthusiastic letter. "There is no man in Europe," he wrote, "who loves you as I do; all marvel, like Nelson, at your great exploits, but he loves you for your contempt of wealth". Someone called Suvorov "the land Nelson"; Nelson was very flattered by this. Someone else said that there is a very great similarity in appearance between the Russian Generalissimo and the British Admiral. Rejoicing at this, Nelson added in a letter to Suvorov that although his, Nelson's, deeds can not equal with those of Suvorov, but he asked Suvorov not to deprive him of the dear name of a loving brother and sincere friend. Suvorov answered Nelson in the same way, and expressed his pleasure that their portraits certify the similarity existing between the originals, but in particular was proud of the fact that the two were alike in their way of thinking.[135]

He also received a warm welcome from his old associate, the Prince of Coburg. The Grand Duke Constantine went to Coburg, through whom Suvorov conveyed a letter or bow to the Prince and via the same Grand Duke received a reply. The Prince called him the greatest hero of his time, thanked him for his memory, lamented the Russian army's removal to the fatherland and lamented the bitter fate of Germany. Suvorov replied to the Prince and said among other things that the entire reason for the failure lies in the differences of systems, and if the systems do not come together, there is no point in starting a new campaign.[135]

Furthermore, a little earlier he had correspondence with Archduke Charles, which, however, was of a sharp nature.[136] Suvorov received greetings and congratulations even from strangers.[135]

Early in 1800, Suvorov returned to Saint Petersburg. Paul, for some reason, refused to give him an audience, and, worn out and ill, the old veteran died a few days afterwards on 18 May 1800, at Saint Petersburg.[32] The main reason for the newly emerged disfavor of Emperor Paul to Suvorov remains uncertain.[137] Suvorov was meant to receive the funeral honors of a Generalissimo, but was buried as an ordinary field marshal due to Paul's direct interference. Lord Whitworth, the British ambassador, and the poet Gavrila Derzhavin were the only persons of distinction present at the funeral. Suvorov lies buried in the Church of the Annunciation in the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, the simple inscription on his grave stating, according to his own direction, "Here lies Suvorov".[32]

Indicates a favorable outcome Indicates an unfavorable outcome Indicates an uncertain outcome

| № | Date(s) | Clash(es) | Type(s) | Conflict(s) | Opponent(s) | Location(s) | Outcome(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 4 May – 2 July 1758 | Siege of Olmütz[citation needed] | Siege | Seven Years' War | ? | Margraviate of Moravia | ? |

| 2. | 25 July 1759 | Combat of Crossen | Open Battle | Seven Years' War | Margraviate of Brandenburg | Victory | |

| 3. | 12 August 1759 | Battle of Kunersdorf | Open Battle | Seven Years' War | Margraviate of Brandenburg | Decisive victory | |

| 4. | October 1760 | Raid on Berlin | Raid; Occupation |

Seven Years' War | Margraviate of Brandenburg | Berlin occupied for three days | |

| 5. | 1761 | Combat of Reichenbach | Open Battle | Seven Years' War | Austrian Silesia | Victory | |

| 6. | 1761 | Skirmish of Schweidnitz | Open Battle | Seven Years' War | Austrian Silesia | Victory | |

| 7. | 15 September 1761 | Combat of Landsberg | Open Battle | Seven Years' War | Margraviate of Brandenburg | Victory | |

| 8. | 1761 | Combat of the Friedberg Forest | Open Battle | Seven Years' War | Prussia | Victory | |

| 9. | 11 October 1761 | Storming of Golnau[138] | Storming Fortifications | Seven Years' War | Prussia | Victory | |

| 10. | 20–21 November 1761 | Assault on Neugarten | FIBUA | Seven Years' War | Margraviate of Brandenburg | Victory[139] | |

| 11. | 1761 | Combat of Stargard | Open Battle | Seven Years' War | Province of Pomerania | Victory | |

| 12. | 24 August – 16 December 1761 | Third Siege of Kolberg | Siege | Seven Years' War | Province of Pomerania | Victory | |

| 13. | 13 September 1769 | Battle of Orzechowo | Open Battle | War of the Bar Confederation | Brest Litovsk Voivodeship | Decisive victory | |

| 14. | 1770 | Combat of Nawodzice | Open Battle | War of the Bar Confederation | Sandomierz Voivodeship | Victory | |

| 15. | July 1770 | Combat of Opatów | Open Battle | War of the Bar Confederation | Sandomierz Voivodeship | Victory | |

| 16. | 20 February 1771 | Lanckorona | Open Battle | War of the Bar Confederation | Kraków Voivodeship | Victory | |

| 17. | 20 February 1771 | Lanckorona | Storming Fortifications | War of the Bar Confederation | Kraków Voivodeship | Withdrew[140] | |

| 18. | 27 February 1771 | Assault on Rachów | FIBUA | War of the Bar Confederation | Lublin Voivodeship | Victory | |

| 19. | 27–28 February 1771 | Combat of Kraśnik | Open Battle | War of the Bar Confederation | Lublin Voivodeship | Victory | |

| 20. | 20 May 1771 | Action of the Tyniec Abbey | Storming Fortifications | War of the Bar Confederation | Kraków Voivodeship | Withdrew[142] | |

| 21. | 21 May 1771 | Lanckorona | Open Battle | War of the Bar Confederation | Kraków Voivodeship | Decisive victory | |

| 22. | 22 May 1771 | Combat of Zamość | Open Battle | War of the Bar Confederation | Ruthenian Voivodeship | Victory | |

| 23. | 24 September 1771 | Battle of Stołowicze | Open Battle | War of the Bar Confederation | Nowogródek Voivodeship | Decisive victory | |

| 24. | 24 January – 26 April 1772 | Siege of the Kraków Castle | Siege | War of the Bar Confederation | Kraków Voivodeship | Victory | |

| 25. | 8 May 1773 | Combat of Oltenița | Open Battle | Sixth Russo-Turkish War | Wallachia | Victory | |

| 26. | 21 May 1773 | Turtukaya

|

Open Battle; Storming Fortifications |

Sixth Russo-Turkish War | Ottoman Bulgaria | Decisive victory | |

| 27. | 28 June 1773 | Turtukaya

|

Storming Fortifications; Open Battle |

Sixth Russo-Turkish War | Ottoman Bulgaria | Decisive victory | |

| 28. | 14 September 1773 | Defence of Hirsovo[143] | Storming Fortifications; Open Battle |

Sixth Russo-Turkish War | Dobruja | Victory | |

| 29. | 20 June 1774 | Battle of Kozludzha | Open Battle | Sixth Russo-Turkish War | Ottoman Bulgaria | Decisive victory | |

| 30. | 1 October 1783 | Battle of the Laba | Open Battle | Kuban Nogai uprising | Kuban | Decisive victory | |

| 31. | 11–12 October 1787 | Battle of Kinburn | Storming Fortifications;[144] Open Battle |

Seventh Russo-Turkish War | Silistra Eyalet | Decisive victory | |

| 32. | July – 17 December 1788 | Siege of Ochakov | Siege | Seventh Russo-Turkish War | Silistra Eyalet | Victory | |

| 33. | 1 August 1789 | Battle of Focșani | Open Battle | Seventh Russo-Turkish War | Moldavia | Decisive victory | |

| 34. | 22 September 1789 | Battle of Rymnik | Open Battle | Seventh Russo-Turkish War | Wallachia | Decisive victory | |

| 35. | 21–22 December 1790 | Storming of Izmail | Storming Fortifications | Seventh Russo-Turkish War | Silistra Eyalet | Decisive victory | |

| 36. | 15 September 1794 | Combat of Kobryń | Open Battle | Polish Revolution of 1794 | Brest Litovsk Voivodeship | Victory | |

| 37. | 17 September 1794 | Battle of Krupczyce | Open Battle | Polish Revolution of 1794 | Brest Litovsk Voivodeship | Decisive victory | |

| 38. | 19 September 1794 | Combat of Dywin | Open Battle | Polish Revolution of 1794 | Brest Litovsk Voivodeship | Victory | |

| 39. | 19 September 1794 | Battle of Terespol (Battle of Brest) |

Open Battle | Polish Revolution of 1794 | Brest Litovsk Voivodeship | Decisive victory | |

| 40. | 26 October 1794 | Battle of Kobyłka | Open Battle | Polish Revolution of 1794 | Masovian Voivodeship | Victory | |

| 41. | 2–4 November 1794 | Storming of Praga | Open Battle; Storming Fortifications |

Polish Revolution of 1794 | Warsaw | Decisive victory | |

| 42. | 21 April 1799 | Capture of Brescia | Surrender | Italian campaign |

Cisalpine Republic | Victory | |

| 43. |

|

Battle of the Adda River

|

Open Battle; Storming Fortifications |

Italian campaign | Cisalpine Republic | Decisive victory | |

| 44. | 16 May 1799 | Battle of San Giuliano (First Battle of Marengo) |

Open Battle | Italian campaign | Piedmontese Republic | Victory | |

| 45. | till 20 June 1799 | Siege of Turin Citadel[146] | Siege | Italian campaign | Turin | Victory | |

| 46. | 17–20 June 1799 | Battle of the Trebbia

|

Open Battle | Italian campaign | Duchy of Parma | Decisive victory | |

| 47. | 15 August 1799 | Battle of Novi | Open Battle; Storming Fortifications[147] |

Italian campaign | Piedmont | Decisive victory | |

| 48. | 24 September 1799 | Battle of the Gotthard Pass | Open Battle | Swiss campaign | Saint-Gotthard Massif | Victory | |

| 49. | 24 September 1799 | Combat of Hospital[148] / Hospental[149] | Open Battle | Swiss campaign | Canton of Waldstätten | Victory | |

| 50. | 24 September 1799 | Battle of Oberalpsee[148] / the Oberalp Pass[150] | Open Battle | Swiss campaign | Canton of Waldstätten; Canton of Raetia |

Victory | |

| 51. | 25 September 1799 | Combat of the Urnerloch[151] | Open Battle | Swiss campaign | Canton of Waldstätten | Victory | |

| 52. | 25 September 1799 | Battle of the Devil's Bridge | Open Battle | Swiss campaign | Canton of Waldstätten | Victory | |

| 53. | 30 September – 1 October 1799 | Battle of the Klöntal | Open Battle | Swiss campaign | Canton of Linth | Victory | |

| 54. | 30 September – 1 October 1799 | Battle of the Muttental | Open Battle | Swiss campaign | Canton of Waldstätten | Decisive victory | |

| 56. | 1 October 1799 | Battle of Glarus[152] | Open Battle | Swiss campaign | Canton of Linth | Victory | |

| 55. | 1 October 1799 | Combat of Netstal | Open Battle | Swiss campaign | Canton of Linth | Victory | |

| 57. | 5 October 1799 | Combats of Schwanden[153] | Open Battle | Swiss campaign | Canton of Linth | Victory |