| Part of a series on |

| The Holocaust |

|---|

|

In the decades since the Holocaust, some national governments, international bodies and world leaders have been criticized for their failure to take appropriate action to save the millions of European Jews, Roma, and other victims of the Holocaust. Critics say that such intervention, particularly by the Allied governments, might have saved substantial numbers of people and could have been accomplished without the diversion of significant resources from the war effort.[1]

Other researchers have challenged such criticism. Some have argued that the idea that the Allies took no action is a myth—that the Allies accepted as many German Jewish immigrants as the Nazis would allow—and that theoretical military action by the Allies, such as bombing the Auschwitz concentration camp, would have saved the lives of very few people.[2] Others have said that the limited intelligence available to the Allies—who, as late as October 1944, did not know the locations of many of the Nazi death camps or the purposes of the various buildings within those camps they had identified—made precision bombing impossible.[3]

Allied states

[edit]United Kingdom

[edit]By 1939, about 304,000 of about 522,000 German Jews had fled Germany, including 60,000 to the British Mandate of Palestine (including over 50,000 who had taken advantage of the Haavara, or "Transfer" Agreement between German Zionists and the Nazis), but British immigration quotas limited the number of Jewish emigrants to Palestine.[4] In March 1938, Germany annexed Austria and made the 200,000 Jews of Austria stateless refugees. In September, the British and French governments allowed Germany the right to occupy and annex the Sudetenland of Czechoslovakia, and in March 1939, Hitler occupied the remainder of the country, making a further 200,000 Jews stateless.[citation needed]

In 1939, British policy as stated in its 1939 White Paper capped Jewish immigration to Mandatory Palestine at 75,000 over the next five years, after which all further Jewish immigration would be made subject to Arab approval. The British government had offered homes for Jewish immigrant children and proposed Kenya as a haven for Jews, but refused to back a Jewish state or facilitate Jewish settlement, contravening the terms of the League of Nations Mandate over Palestine.[citation needed]

Before, during and after the war, the British government limited Jewish immigration to Mandatory Palestine so as to avoid a negative reaction from Palestinian Arabs. In the summer of 1941, however, Chaim Weizmann estimated that with the British ban on Jewish immigration, when the war was over, it would take two decades to get 1.5 million Jews to Palestine from Europe through clandestine immigration; David Ben-Gurion had originally believed 3 million could be brought in ten years. Thus Palestine it has been argued by at least one writer, once war had begun—could not have been the saviour of anything other than a small minority of those Jews murdered by the Nazis.[5]

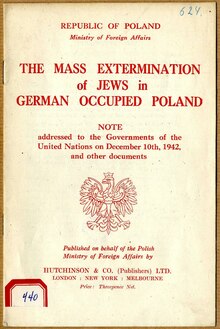

The British government, along with all UN member nations, received credible evidence about the Nazi attempts to exterminate the European Jewry as early as 1942 from the Polish government-in-exile. Titled "The Mass Extermination of the Jews in German Occupied Poland", the report provided a detailed account of the conditions in the ghettos and their liquidation.[6] Additionally the Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden met with Jan Karski, courier to the Polish resistance who, having been smuggled into the Warsaw ghetto by the Jewish underground, as well as having posed as an Estonian guard at Bełżec transit camp, provided him with detailed eyewitness accounts of Nazi atrocities against the Jews.[7][8]

These lobbying efforts triggered the Joint Declaration by Members of the United Nations of 17 December 1942 which made public and condemned the mass extermination of the Jews in Nazi-occupied Poland. The statement was read to British House of Commons in a floor speech by Foreign secretary Anthony Eden, and published on the front page of the New York Times and many other newspapers.[9] BBC radio aired two broadcasts on the final solution during the war: the first at 9 am on 17 December 1942, on the UN Joint Declaration, read by Polish Foreign Minister in-exile Edward Raczynski, and the second during May 1943, Jan Karski's eyewitness account of mass Jewish executions, read by Arthur Koestler.[10] However, the political rhetoric and public reporting was not followed up with military action by the British government- an omission that has been the source of significant historical debate.[citation needed]

United States

[edit]Initially, America refused to accept Jewish refugees who were in need. Between 1933 and 1945, the United States accepted more refugees than any other country: around 132,000. It has faced criticism for not admitting more refugees, especially during the war, as even the immigration quotas available went unfilled.[11][12]

In Washington, President Roosevelt, sensitive to the importance of his Jewish constituency, consulted with Jewish leaders. He followed their advice to not emphasize the Holocaust for fear of inciting antisemitism in the U.S. Historians argue that after Pearl Harbor:

- Roosevelt and his military and diplomatic advisers sought to unite the nation and blunt Nazi propaganda by avoiding the appearance that the United States was fighting a war for the Jews. They did not tolerate any potentially divisive initiatives nor did they tolerate any diversion from their campaign to win the war as quickly and decisively as possible....Success on the battlefield, Roosevelt and his advisers believed, was the only sure way to save the surviving Jews of Europe.[13]

Historian Laurel Leff has written on modern day attempts by State Department historians to whitewash the indifference of certain US consular officials dealing with visa applications of Jewish refugees attempting to flee from Nazi Germany. She contends that the record of those diplomats was far worse than the State Department today is willing to admit, and presents a number of examples in which the actions of US officials directly prevented imperiled Jews from finding sanctuary in the United States even though immigration quotas had not been filled.[14]

Soviet Union

[edit]The Soviet Union was invaded and partially occupied by Axis forces. Approximately 300,000 to 500,000 Soviet Jews served in the Red Army during the conflict.[15] The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee established in 1941, was active in propagandising for the Soviet war effort but was treated with suspicion. The Soviet press, tightly censored, often deliberately obscured the particular anti-Jewish motivation of the Holocaust.[16]

Allied governments in exile

[edit]Poland

[edit]

The Nazis built the majority of their death camps in German occupied Poland which had a Jewish population of 3.3 million. From 1941 on, the Polish government-in-exile in London played an essential part in revealing Nazi crimes[17] providing the Allies with some of the earliest and most accurate accounts of the ongoing Holocaust of European Jews.[18][19] Titled "The Mass Extermination of the Jews in German Occupied Poland", the report provided a detailed account of the conditions in the ghettos and their liquidation.[20][21] Though its representatives, like the Foreign Minister Count Edward Raczyński and the courier of the Polish Underground movement, Jan Karski, called for action to stop it, they were unsuccessful. Most notably, Jan Karski met with British Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden as well as US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, providing the earliest eyewitness accounts of the Holocaust.[22][8] Roosevelt heard him out however seemed uninterested, asking about the condition of Polish horses but not one question about the Jews.[23]

The report that the Polish Foreign Minister in-exile, Count Edward Raczyński sent on 10 December 1942, to all the Governments of the United Nations was the first official denunciation by any Government of the mass extermination and of the Nazi aim of total annihilation of the Jewish population. It was also the first official document singling out the sufferings of European Jews as Jews and not only as citizens of their respective countries of origin.[18] The report of 10 December 1942 and the Polish Government's lobbying efforts triggered the Joint Declaration by Members of the United Nations of 17 December 1942 which made public and condemned the mass extermination of the Jews in German-occupied Poland. The statement was read to British House of Commons in a floor speech by Foreign secretary Anthony Eden, and published on the front page of the New York Times and many other newspapers.[9] Additionally BBC radio aired two broadcasts on the final solution during the war which were prepared by the Polish government-in-exile.[24] This rhetoric, however, was not followed up by military action by Allied nations. During an interview with Hannah Rosen in 1995, Karski said about the failure to rescue most of the Jews from mass murder, "The Allies considered it impossible and too costly to rescue the Jews, because they didn't do it. The Jews were abandoned by all governments, church hierarchies and societies, but thousands of Jews survived because thousands of individuals in Poland, France, Belgium, Denmark, Holland helped to save Jews." [25]

During the occupation period, 3 million Polish Jews were killed. This represented 90 percent of the pre-war population and half of all Jews killed in the Holocaust.[26] Additionally the Nazis ethnically cleansed another 1.8-2 million Poles, bringing Poland's Holocaust death toll to around 4.8-5 million people.[27][28] After the war Poland defied both the wishes of the Allied and Soviet governments, allowing Jewish emigration to Mandatory Palestine. Around 200,000 Jews availed themselves of this opportunity, leaving only around 100,000 Jews in Poland.[citation needed]

Neutral states

[edit]Portugal

[edit]Portugal had been ruled from 1933 by an authoritarian political regime led by António de Oliveira Salazar which had been influenced by contemporary fascist regimes. However, it was unusual in not explicitly incorporating Antisemitism in its own ideology.[29] In spite of this, Portugal had introduced immigration measures which discriminated against Jewish refugees in 1938. Its rules on issuing transit visas were further tightened at the time of the German invasion of France in May–June 1940. Aristides de Sousa Mendes, the country's consul at Bordeaux, nonetheless issued large numbers of visas to refugees, including Jews, fleeing the German advance but was later officially sanctioned for his actions.[30] Although few Jews were permitted to settle in Portugal itself, some 60,000 to 80,000 Jewish refugees passed through Portugal which, especially before 1942, was a major route for refugees fleeing to the United Kingdom and the United States.[31] A number of prominent Jewish aid agencies were permitted to establish offices in Lisbon.

Portugal's Ministry of Foreign Affairs received information from its consuls in German-occupied Europe from 1941 about the escalation of the persecution of Jews. The historian Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses writes that it was nonetheless considered insignificant:

Salazar's analysis of the European situation [...] was based on an old-fashioned brand of realpolitik which saw states and their leaders acting out of reasonable and quantifiable considerations. The murderous racial enterprise that drove the Third Reich appears to have bypassed Salazar, despite the information that must have been accessible to him (very little of which survives, however, in his archive). The Portuguese press, meanwhile, was prevented from reporting on the Final Solution as its details became known, and Salazar never made a pronouncement on the subject. The fate of Europe's Jewish population was not seen as an issue that affected the national interest...[32]

Salazar's regime took limited steps to intervene on behalf of certain Portuguese Jews living in German-occupied Europe from 1943 and did succeed in saving small numbers in Vichy France and German-occupied Northern Greece. After lobbying from Moisés Bensabat Amzalak, a Jewish regime loyalist, Salazar also unsuccessfully attempted to intercede with the German government on behalf of the Portuguese Sephardic community in the German-occupied Netherlands. Alongside Spanish and Swedish diplomatic missions, the Portuguese Legation in Hungary also issued papers to some 800 Hungarian Jews in late 1944.[31]

Spain

[edit]

Francoist Spain remained neutral during the conflict but retained close economic and political links with Nazi Germany. It was ruled throughout the period by the authoritarian regime of Francisco Franco which had come to power with German and Italian support during the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). Paul Preston wrote that "one of Franco's central beliefs was the 'Jewish–masonic–Bolshevik conspiracy'. He was convinced that Judaism was the ally of both American capitalism and Russian communism".[33] Public Jewish religious services, like their Protestant equivalents, had been forbidden since the Civil War.[34] José Finat y Escrivá de Romaní, the Director of Security, ordered a list of Jews and foreigners in Spain to be compiled in May 1941. The same year, Jewish status was marked on identity papers for the first time.[34][35]

Historically, Spain had attempted to extend its influence over Sephardic Jews in other parts of Europe. Many Sephardic Jews living in German-occupied Europe either held Spanish citizenship or protected status. The German occupation authorities issued a series of measures requiring neutral states to repatriate their Jewish citizens and the Spanish government ultimately accepted 300 Spanish Jews from France and 1,357 from Greece but failed to intervene on behalf of the majority of Spanish Jews in German-occupied Europe.[36] Michael Alpert writes that "to save these Jews would mean having to accept that they had the right to repatriation, to live as residents in Spain, or so it seems to have been feared in Madrid. While, on the one hand, the Spanish regime, as always inconsistently, issued instructions to its representatives to try to prevent the deportation of Jews, on the other, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Madrid allowed the Nazis and Vichy puppet government to apply anti-Jewish regulations to people whom Spain should have protected".[36] In addition, Spanish authorities permitted 20,000 to 35,000 Jews to travel through Spanish territory on transit visas from France.[37][38]

Ángel Sanz Briz, a Spanish diplomat, protected several hundred Jews in Hungary in 1944. After he was ordered to withdraw from the country ahead of the Red Army's advance, he encouraged Giorgio Perlasca, an Italian businessman, to pose as the Spanish consul-general and continue his activities. In this way, 3,500 Jews are thought to have been saved.[39] Stanley G. Payne described Sanz Briz's actions as "a notable humanitarian achievement by far the most outstanding of anyone in Spanish government during World War II" but argued that he "might have accomplished even more had he received greater assistance from Madrid".[40] In the aftermath of the war, "a myth was carefully constructed to claim that Franco's regime had saved many Jews from extermination" as a means to deflect foreign criticism away from allegations of active collaboration between the Franco and Nazi regimes.[35]

Sweden

[edit]Sweden remained neutral throughout the conflict but also retained close economic ties with Nazi Germany. German forces invaded and occupied Norway and Denmark in April 1940 while Finland entered into a de facto alliance with Nazi Germany from 1941 meaning that Sweden was drawn towards the Axis sphere of influence and German soldiers were even able to travel through its territory on leave from German-occupied Norway until 1943. Sweden itself had only a small Jewish population and had tightened its immigration policies in the interwar years which meant that few Jewish refugees had been taken into the country before the war. Swedish society remained highly conservative and introspective, although antisemitism remained marginal in national politics.[41] In some circles, there was some sympathy for Nazi war aims and anti-communism as well as Nazi racial theories which overlapped with the Nordicism. Several hundred Swedish nationals volunteered to serve in the Waffen-SS and some were reported to have served as guards at Treblinka extermination camp.[42]

In Sweden, the Ministry for Foreign Affairs received news about the policy of extermination. In a chance discussion in a train, the Swedish diplomat Göran von Otter was told of the extermination of Jews at Belzec extermination camp by an SS officer in August 1942. He reported the information to the Ministry in the hope that it would publicly condemn the atrocities, although no action was taken.[43] Even so, the historian Paul A. Levine writes that "Swedish officials, and in fact much of the newspaper-reading public, had as much or more information about many details of the 'Final Solution' than their counterparts in other neutral or Allied countries".[44] Although coverage varied by newspaper, there were widespread reports in the Swedish press of the extermination of Jews in German-occupied Europe throughout much of the subsequent period.[45]

The authorities in German-occupied Norway began a series of operations in October 1942 to round up the country's small Jewish population, estimated at 2,000. The news was reported in the Swedish press[46] but the Ministry for Foreign Affairs was "rather slow to realise what was going on".[47] Most Norwegian Jews were detained in the first operations but the Norwegian resistance did succeed in smuggling an estimated 1,100 Jews across the border into Sweden in the so-called Carl Fredriksens Transport.[47] Subsequently, attitudes among Swedish officials began to change. After news of the imminent detention of Danish Jews was leaked, the Danish Resistance successfully evacuated 8,000 Danish Jews to Sweden, with the approval of the Swedish government, in October and November 1943.[48] After American pressure, the Swedish government also despatched a diplomatic mission to Hungary in July 1944 to seek to use Hungary's peculiar diplomatic status to intercede on behalf of Hungarian Jews. Raoul Wallenberg ultimately issued several hundred visas and 10,000 protective passes with the aid of the Swedish chargé d'affaires in Budapest Per Anger but was detained after Soviet forces captured the Budapest and is thought to have been executed.[48] In the final months of the war, the Swedish Red Cross was able to evacuate substantial numbers of political prisoners from German concentration camps in the so-called White Buses including a small number of Danish Jews interned in the Theresienstadt Ghetto.

In the post-war period, the Swedish government placed emphasis on its humanitarian actions to save Jews as a means of deflecting criticism of its economic and political relations with Nazi Germany. Historian Ingrid Lomfors states that this "sowed the seed of the image of Sweden as a 'humanitarian superpower'" in post-war Europe and its prominent involvement in the United Nations.[43] Göran Persson, a former Swedish Prime Minister, founded the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance in 1998.

Switzerland

[edit]Jews who were about to emigrate [… from Germany] had to obtain passports. At first, nothing in a passport indicated whether the bearer was a Jew. Apparently, no one thought of making any changes in passports issued to Jews or held by Jews until action was initiated by officials of a foreign country. That country was Switzerland.[49]

Of the five neutral countries of continental Europe, Switzerland has the distinction of being the only one to have promulgated a German antisemitic law.[50] (Excluding European microstates, the five European neutral states were Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and Turkey.) The country closed its French border to refugees for a period from 13 August 1942, and did not allow unfettered access to Jews seeking refuge until 12 July 1944.[50] In 1942 the President of the Swiss Confederation, Philipp Etter as a member of the Geneva-based ICRC even persuaded the committee not to issue a condemnatory proclamation concerning German "attacks" against "certain categories of nationalities".[51][52]

Turkey

[edit]Turkey remained officially neutral and maintained diplomatic relations with Nazi Germany.[53] During the war, Turkey denaturalized 3,000 to 5,000 Jews living abroad; 2,200 and 2,500 Turkish Jews were ultimately deported to extermination camps such as Auschwitz and Sobibor; and several hundred interned in Nazi concentration camps. When Nazi Germany encouraged neutral countries to repatriate their Jewish citizens, Turkish diplomats received instructions to avoid repatriating Jews even if they could prove their Turkish nationality.[54]

Turkey was also the only neutral country to implement anti-Jewish laws during the war.[55] Between 1940 and 1944, around 13,000 Jews passed through Turkey from Europe to Mandatory Palestine.[56] More Turkish Jews suffered as a result of discriminatory policies during the war than were saved by Turkey.[57] Although Turkey has promoted the idea that it was a rescuer of Jews during the Holocaust, this is considered a myth by historians.[58][53] This myth has been used to promote Armenian genocide denial.[59]

Latin American states

[edit]Most of the states in Latin America remained neutral for much or all of World War II. The region, in particular Argentina and Brazil, had historically received large numbers of European immigrants including significant numbers of Jews from Eastern Europe. Immigration restrictions were introduced in the 1920s and 1930s, however, in response to nationalist unrest and the Great Depression. Antisemitism remained common in many parts of Latin American society.

Brazil's foreign ministry, for example, ordered its consulates in Europe to deny visas to people of "Semitic origin" in the 1930s. These stipulations were followed by many Brazilian diplomats who held strong antisemitic views. However, some such as Luis Martins de Souza Dantas, Brazil's ambassador in Vichy France, actively disobeyed their instructions and continued to issue visas to Jews as late as 1941.[60]

As neutral states, Latin American diplomats remained in German-occupied Europe for much of the conflict. Gonzalo Montt Rivas, Chilean consul in Prague, informed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in a report in November 1941 that "German triumph [in the war] will leave Europe freed of Semites". According to the historian Richard Breitman, his reports "reveal considerable access to the thinking of Nazi officials" which he speculates may have originated from Montt's friendly relations with the Foreign Intelligence Service of the Reich Security Main Office. Chilean diplomatic correspondence, including Montt's November dispatch, was regularly intercepted by British intelligence services and shared with their American counterparts.[61]

Some Latin American Jews were living in Europe at the time of the Holocaust. Although warned on several occasions by the German authorities to repatriate its Jewish citizens, the Argentine regime refused to repatriate its approximately 100 nationals living in German-occupied Europe before the country severed diplomatic relations with Nazi Germany under Allied pressure in January 1944. All are believed to have been exterminated.[62]

Vatican and Catholic Church

[edit]The pontificate of Pius XII coincided with the Second World War and the Nazi Holocaust, which saw the industrialized mass murder of millions of Jews and others by Adolf Hitler's Germany. Pius employed diplomacy to aid the victims of the Nazis during the war and, through directing his Church to provide discreet aid to Jews, saved thousands of lives.[63] Pius maintained links to the German Resistance, and shared intelligence with the Allies. His strongest public condemnation of genocide was, however, considered inadequate by the Allied Powers, while the Nazis viewed him as an Allied sympathizer who had dishonoured his policy of Vatican neutrality.[64] In Rome action was taken to save many Jews in Italy from deportation, including sheltering several hundred Jews in the catacombs of St. Peter's Basilica. In his Christmas addresses of 1941 and 1942, the pontiff was forceful on the topic but did not mention the Nazis by name. The Pope encouraged the bishops to speak out against the Nazi regime and to open the religious houses in their dioceses to hide Jews. At Christmas 1942, once evidence of the industrial slaughter of the Jews had emerged, he voiced concern at the murder of "hundreds of thousands" of "faultless" people because of their "nationality or race". Pius intervened to attempt to block Nazi deportations of Jews in various countries from 1942 to 1944.

When 60,000 German soldiers and the Gestapo occupied Rome in 1943, thousands of Jews were hiding in churches, convents, rectories, the Vatican and the papal summer residence. According to Joseph Lichten, the Vatican was called upon by the Jewish Community Council in Rome to help fill a Nazi demand of one hundred pounds of gold. The council had been able to muster seventy pounds, but unless the entire amount was produced within thirty-six hours had been told three hundred Jews would be imprisoned. The Pope granted the request, according to Chief Rabbi Zolli of Rome.[65] Despite the payment of the ransom 2,091 Jews were deported on October 16, 1943, and most of them died in Germany.

Upon his death in 1958, Pius was praised emphatically by the Israeli Foreign Minister and other world leaders. But his insistence on Vatican neutrality and avoidance of naming the Nazis as the evildoers of the conflict became the foundation for contemporary and later criticisms from some quarters. Studies of the Vatican archives and international diplomatic correspondence continue.

Non-governmental organisations

[edit]International Committee of the Red Cross

[edit]The International Committee of the Red Cross did relatively little to save Jews during the Holocaust and discounted reports of the organized Nazi genocide, such as of the murder of Polish Jewish prisoners that took place at Lublin. At the time, the Red Cross justified its inaction by suggesting that aiding Jewish prisoners would harm its ability to help other Allied POWs. In addition, the Red Cross claimed that if it would take a major stance to improve the situation of those European Jews, the neutrality of Switzerland, where the International Red Cross was based, would be jeopardized.

Today, the Red Cross acknowledges its passivity during the Holocaust and has apologized for this.[66]

Jewish organisations

[edit]Jewish issue at international conferences

[edit]Évian Conference

[edit]The Évian Conference was convened at the initiative of Franklin D. Roosevelt in July 1938 to discuss the problem of Jewish refugees. For ten days, from July 6 to July 15, delegates from thirty-two countries met at Évian-les-Bains, France. However, most western countries were reluctant to accept Jewish refugees, and the question was not resolved.[67][68] The Dominican Republic was the only country willing to accept Jewish refugees—up to 100,000.[69]

Bermuda Conference

[edit]The UK and the US met in Bermuda in April 1943 to discuss the issue of Jewish refugees who had been liberated by Allied forces and the Jews who remained in Nazi-occupied Europe. The Bermuda Conference led to no change in policy; the Americans would not change their immigration quotas to accept the refugees, and the British would not alter its immigration policy to permit them to enter Palestine.[70][71]

The failure of the Bermuda Conference prompted U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, the only Jewish member of Franklin D. Roosevelt's cabinet, to publish a white paper entitled Report to the Secretary on the Acquiescence of this Government to the Murder of the Jews.[72] This led to the creation of a new agency, the War Refugee Board.[73]

Japan and Japanese-occupied Southeast Asia

[edit]In 1936, German-Japanese Pact was concluded between Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan.[74] However, on December 6, 1938, the Japanese government made a decision of prohibiting the expulsion of the Jews in Japan, Manchukuo, and the rest of Japanese-occupied China.[75] On December 31, Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka told the Japanese Army and Navy to receive Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany.[citation needed] Diplomat Chiune Sugihara granted more than 2,000 transit visas and saved 6,000 Jewish refugees from Lithuania.[76][77]

Response after the Holocaust

[edit]Nuremberg Trials

[edit]The international response to the war crimes of World War II and the Holocaust was to establish the Nuremberg international tribunal. Three major wartime powers, the US, USSR and Great Britain, agreed to punish those responsible. The trials brought human rights into the domain of global politics, redefined morality at the global level, and gave political currency to the concept of crimes against humanity, where individuals rather than governments were held accountable for war crimes.[78] Twelve were sentenced to death, ten were hanged,[a] seven were sentenced to varying prison lengths and three were acquitted. Four organisations were ruled to be criminal – The Leadership Corps of the Nazi Party, the SS, the Gestapo, and the SD.

Genocide

[edit]Towards the end of World War II, Raphael Lemkin, a lawyer of Polish-Jewish descent, aggressively pursued within the halls of the United Nations and the United States government the recognition of genocide as a crime. Largely due to his efforts and the support of his lobby, the United Nations was propelled into action. In response to Lemkin's arguments, the United Nations adopted the term in 1948 when it passed the "Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide".[79]

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

[edit]Many believe that the extermination of Jews during the Holocaust inspired the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1948. This view has been challenged by recent historical scholarship. One study has shown that the Nazi slaughter of Jews went entirely unmentioned during the drafting of the Universal Declaration at the United Nations, though those involved in the negotiations did not hesitate to name many other examples of Nazi human rights violations.[80] Other historians have countered that the human rights activism of the delegate René Cassin of France, who received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1968 for his work on the Universal Declaration, was motivated in part by the death of many Jewish relatives in the Holocaust and his involvement in Jewish organisations providing aid to Holocaust survivors.[81]

See also

[edit]- Auschwitz bombing debate

- History of the Jews during World War II

- Holocaust victims

- Kindertransport

- Rescue of Jews during the Holocaust

- Responsibility for the Holocaust

- Riegner Telegram

- Righteous Among the Nations

- Role of the international community in the Rwandan genocide

- Secondary antisemitism

- Szmul Zygielbojm

- Witold Pilecki

- World War II

Notes

[edit]- ^ One of the sentenced committed suicide and another was sentenced in absentia

References

[edit]- ^ Morse 1968; Power 2002; Wyman 1984.

- ^ Rubinstein 1997.

- ^ Kitchens 1994.

- ^ US Holocaust Museum Holocaust Encyclopedia: "Refugees". and "German Jewish Refugees 1933-1939".

- ^ Segev 2000, p. 461.

- ^ File:The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied.pdf

- ^ Karski, Jan (2013). Story of a Secret State. Georgetown University Press.

- ^ a b Jones, Nigel (4 May 2011). "Story of a Secret State by Jan Karski: review". The Daily Telegraph.

Karski reached London where he had an interview with the foreign secretary Anthony Eden, the first of many top officials to effectively ignore his account of the Nazis' systematic effort to exterminate European Jewry. The very enormity of Karski's report paradoxically worked against him being believed, and paralysed any action against the killings. Logistically unable to reach Poland, preoccupied with fighting the war on many fronts, and unwilling to believe even the Nazis capable of such bestiality, the Allies put the Holocaust on the back burner. When Karski took his tale across the Atlantic, the story was the same. President Roosevelt heard him out, then asked about the condition of horses in Poland."

- ^ a b "11 Allies Condemn Nazi War on Jews". The New York Times. December 18, 1942. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- ^ Karski, Jan (2011). Story of a Secret State: My Report to the World. Penguin Classics (2nd ed.). p. Appendix p.3. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ "Immigration Policy in World War II | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History". www.gilderlehrman.org. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "How Many Refugees Came to the United States from 1933-1945? - Americans and the Holocaust - United States Holocaust Memorial Museum". exhibitions.ushmm.org.

- ^ Richard Breitman and Allan J. Lichtman, FDR and the Jews (2013) p. 318–319. The authors also argue: "Roosevelt played no apparent role in the decision not to bomb Auschwitz. Even if the matter had reached his desk, however, he would not likely have contravened his military. Every major American Jewish leader and organization that he respected remained silent on the matter, as did all influential members of Congress and opinion-makers in the mainstream media." p. 321.

- ^ Leff, Laurel (2022-11-24). "Seeking the Middle, Creating a Muddle: The Failed Efforts of State Department Historians to Reinterpret the Role of US Consuls in the Nazi-Era Refugee Crisis". Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs. 16 (2): 229–249. doi:10.1080/23739770.2022.2131269. ISSN 2373-9770. S2CID 254010125.

- ^ Altshuler, Mordechai (2014). "Jewish Combatants in the Red Army Confront the Holocaust". In Murav, Harriet; Estraikh, Gennady (eds.). Soviet Jews in World War II. Boston: Academic Studies Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781618119261.

- ^ Berkhoff, Karel C. (2009). ""Total Annihilation of the Jewish Population": The Holocaust in the Soviet Media, 1941-45". Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. 10 (1): 61–105. doi:10.1353/kri.0.0080. S2CID 159464815.

- ^ "The role of the Polish government-in-exile / Informing the world / History / Auschwitz-Birkenau". auschwitz.org. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

- ^ a b Krzysztof Kania, Edward Raczynski, 1891-1993, Dyplomata i Polityk (Edward Raczynski, 1891-1993, Diplomat and Politician), Wydawnictwo Neriton, Warszawa, 2014, p. 232

- ^ Martin Gilbert, Auschwitz and the Allies, 1981 (Pimlico edition, p.101) "On December 10, the Polish Ambassador in London, Edward Raczynski sent Eden an extremely detailed twenty-one point summary of all the most recent information regarding the killing of Jews in Poland; confirmation, he wrote, "that the German authorities aim with systematic deliberation at the total extermination of the Jewish population of Poland" as well as of the "many thousands of Jews" whom the Germans had deported to Poland from western and Central Europe, and from the German Reich itself."

- ^ Engel (2014)

- ^ The Mass Extermination of the Jews in German Occupied Poland

- ^ The meeting with Roosevelt occurred in the Oval Office on 28 July 1943 "Algemeiner 07/17/2013". Algemeiner.com. 2013-07-17. Retrieved 2014-03-04.

- ^ Claude Lanzmann (4 May 2011). "U.S Holocaust memorial Museum, Claude Lanzmann Interview with Jan Karski". Steven Spielberg Film and Video Archive. Karski first told Roosevelt that the Polish nation was depending on him to deliver them from the Germans. Karski said to Roosevelt, "All hope, Mr. President, has been placed by the Polish nation in the hands of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Karski says that he told President Roosevelt about Belzec and the desperate situation of the Jews. Roosevelt concentrated his questions and remarks entirely on Poland and did not ask one question about the Jews ". Watch the video, or see the full transcript

- ^ The first aired at 9 am on 17 December 1942, on the UN Joint Declaration, read by Polish Foreign Minister in-exile Edward Raczynski, and the second during May 1943, Jan Karski's eyewitness account of mass Jewish executions, read by Arthur Koestler. Karski, Jan Story of a Secret State: My Report to the World, Penguin Classics, 2nd edition (2011) Appendix p.3 ISBN 9781589019836

- ^ "Interview with Jan Karski". Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- ^ Dawidowicz 1975 (1986 ed., ISBN 0-553-34302-5, p. 403)

- ^ This excludes deaths resulting from military or resistance activities which total over a million

- ^ An estimated 1.8–1.9 million non-Jewish Polish citizens have died as a result of the Nazi occupation and the war (Franciszek Piper, Polish scholar and chief historian at Auschwitz). See also "Polish Victims". Holocaust Encyclopedia – USHMM. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Flunser Pimentel 2018, p. 441.

- ^ Flunser Pimentel 2018, p. 442–3.

- ^ a b Flunser Pimentel 2018.

- ^ Ribeiro de Meneses 2009, p. 223.

- ^ Preston 2020, p. 341.

- ^ a b Payne 2008, p. 215.

- ^ a b Preston 2020, p. 342.

- ^ a b Alpert 2009, p. 207.

- ^ Alpert 2009, p. 205.

- ^ Payne 2008, p. 220.

- ^ Payne 2008, p. 234.

- ^ Payne 2008, p. 230.

- ^ Gilmour 2010, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Wiklund, Mats (17 September 2011). "Murky truth of how a neutral Sweden covered up its collaboration with Nazis". The Independent. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ a b Ledel, Johannes (9 November 2020). "Sweden grapples with 'guilty conscience' over ignored Holocaust tip-off". Times of Israel. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Levine 2005, p. 81.

- ^ Zander 2015, p. 287.

- ^ Gilmour 2010, p. 192.

- ^ a b Åmark 2015, p. 310.

- ^ a b Åmark 2015, p. 311.

- ^ Hilberg 2003, p. 173.

- ^ a b Hilberg 1995, pp. 258.

- ^ Hilberg 1995, p. 259.

As can be seen, the proclamation's description of Nazi crimes was vague, and would not even have explicitly mentioned the word Jews. - ^ Favez 1999, p. 88.

- ^ a b Webman, Esther (2014). "Corry Guttstadt, Turkey, the Jews and the Holocaust (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013)". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 46 (2): 426–428. doi:10.1017/S0020743814000361. S2CID 162685190.

- ^ Baer 2020, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Baer 2020, p. 202.

- ^ Ofer, Dalia (1990). Escaping the Holocaust: Illegal Immigration to the Land of Israel, 1939-1944. Oxford University Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-19-506340-0.

- ^ Baer, Marc David (2015). "Corry Guttstadt. Turkey, the Jews, and the Holocaust. Translated from German by Kathleen M. Dell'Orto, Sabine Bartel, and Michelle Miles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013. 353 pp. - I. Izzet Bahar. Turkey and the Rescue of European Jews. New York and London: Routledge, 2015. 308 pp". AJS Review. 39 (2): 467–470. doi:10.1017/S0364009415000252.

- ^ Baer 2020, p. 4.

- ^ Baer, Marc D. (2020). Sultanic Saviors and Tolerant Turks: Writing Ottoman Jewish History, Denying the Armenian Genocide. Indiana University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-253-04542-3.

- ^ Ben-Dror, Graciela. "The Catholic Elites in Brazil and Their Attitude Toward the Jews, 1933–1939". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ Breitman, Richard (15 August 2016). "What Chilean Diplomats Learned about the Holocaust". Nazi War Crimes Interagency Working Group. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ^ Tenembaum, Baruch (9 November 2002). "The fate of Argentine Jews in the Holocaust". The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation. Buenos Aires Herald. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ "Encyclopædia Britannica: "Reflections on the Holocaust"".

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: "Roman Catholicism" – the period of the world wars.

- ^ Lichten, p. 120

- ^ Bugnion, François (5 November 2002). "Dialogue with the past: the ICRC and the Nazi death camps". ICRC. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ Sander, Gordon F. (July 15, 2023). "Inside America's failed, forgotten conference to save Jews from Hitler". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ^ "THE EVIAN CONFERENCE". Holocaust Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ^ "Sosúa: A Refuge for Jews in the Dominican Republic" (PDF). Museum of Jewish Heritage. 8 January 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ Medoff, Rafael (April 2003). "The Allies' Refugee Conference—A 'Cruel Mockery'". David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies. Archived from the original on 13 May 2004. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ Penkower 1988, p. 112.

- ^ Text of report Archived 2017-02-02 at the Wayback Machine, at website of TV show American Experience, a program shown on PBS.

- ^ "Background & Overview of the War Refugee Board". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ^ Goodman & Miyazawa 2000, p. 111.

- ^ Goodman & Miyazawa 2000, pp. 111–12.

- ^ Sugihara 2001, p. 87.

- ^ Pfefferman, Noami (2 November 2000). "Sugihara's Mitzvah". JewishJournal.com. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ Makinda 2005, p. 943.

- ^ Cooper 2008.

- ^ Duranti, Marco. 'The Holocaust, the Legacy of 1789 and the Birth of International Human Rights Law.' Journal of Genocide Research, Vol 14, No. 2 (2012).' [1]

- ^ Winter, Jay and Antoine Prost. René Cassin and Human Rights: From the Great War to the Universal Declaration (Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 346.

Bibliography

[edit]- Alpert, Michael (2009). "Spain and the Jews in the Second World War". Jewish Historical Studies. 42: 201–210. JSTOR 29780130.

- Åmark, Klas (2015). "Swedish anti-Nazism and resistance against Nazi Germany during the Second World War". Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte. 28 (2): 300–312. doi:10.13109/kize.2015.28.2.300. JSTOR 24713121.

- Brazeal, Gregory (2011). "Bureaucracy and the U.S. Response to Mass Atrocity". National Security & Armed Conflict Law Review. 1 (1): 57–71. SSRN 1724387.

- Breitman, Richard, and Allan J. Lichtman. FDR and the Jews (2013).

- Cooper, John (2008). Raphael Lemkin and the Struggle for the Genocide Convention. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Favez, Jean-Claude (1999). The Red Cross and the Holocaust. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Flunser Pimentel, Irene (2018). "Portugal and the Holocaust". In Stuczynski, Claude B.; Feitler, Bruno (eds.). Portuguese Jews, New Christians, and 'New Jews': A Tribute to Roberto Bachmann (PDF). Leiden: Brill. pp. 441–455. ISBN 9789004364974.

- Gilmour, John (2010). Sweden, the Swastika and Stalin: The Swedish Experience in the Second World War. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748627462.

- Goodman, David G.; Miyazawa, Masanori (2000). Jews in the Japanese Mind: The History and Uses of a Cultural Stereotype. Lexington Books.

- Hilberg, Raul (1995) [1992]. Perpetrators Victims Bystanders: The Jewish Catastrophe 1933–1945. London: Secker & Warburg.

- Hilberg, Raul (2003). The Destruction of the European Jews (3rd ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Kennedy, David M. (1999). Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Engel, David (2014). In the Shadow of Auschwitz: The Polish Government-in-exile and the Jews, 1939-1942. UNC Press Books. ISBN 9781469619576.

- Kitchens, James H. (1994). "The Bombing of Auschwitz Re-examined". The Journal of Military History. 58 (2): 233–266. doi:10.2307/2944021. JSTOR 2944021.

- Lawson, Tom (2006). The Church of England and the Holocaust: Christianity, Memory and Nazism. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781843832195.

- Leff, Laurel (2005). Buried by the Times: The Holocaust and America's Most Important Newspaper. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81287-0.

- Levine, Paul A. (2005). "Whither Holocaust Studies in Sweden? Some Thoughts on Levande Historia and Other Matters Swedish". Holocaust Studies. 11 (1): 75–98. doi:10.1080/17504902.2005.11087141.

- Makinda, Sam (2005). "Following postnational signs: the trail of human rights". Futures. 37 (9): 943–957. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2005.01.009.

- Medoff, Rafael (2008). Blowing the Whistle on Genocide: Josiah E. DuBois, Jr. and the Struggle for an American Response to the Holocaust. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press.

- Morse, Arthur D. (1968). While Six Million Died: A Chronicle of American Apathy. New York, NY: Random House.

- Novick, Peter (1999). The Holocaust in American Life. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

- Payne, Stanley G. (2008). Franco and Hitler: Spain, Germany and World War II. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300122824.

- Penkower, Monty Noam (1988). The Jews Were Expendable: Free World Diplomacy and the Holocaust. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press.

- Power, Samantha (2002). "A Problem from Hell": America and the Age of Genocide. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Preston, Paul (2020). A People Betrayed: A History of Corruption, Political Incompetence and Social Division in Modern Spain (1st American ed.). New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation. ISBN 9780871408686.

- Ribeiro de Meneses, Filipe (2009). Salazar: A Political Biography (1st ed.). New York: Enigma Books. ISBN 978-1-929631-90-2.

- Rubinstein, William D. (1997). The Myth of Rescue: Why the Democracies Could Not Have Saved More Jews from the Nazis. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Segev, Tom (2000). One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs Under British Mandate. London: Little, Brown.

- Sugihara, Seishirō (2001). Chiune Sugihara and Japan's Foreign Ministry: Between Incompetence and Culpability, Part 2. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- Tokayer, Marvin; Swartz, Mary (2004). The Fugu Plan: The Untold Story Of The Japanese And The Jews During World War II. Gefen Publishing House; 1st Gefen Ed edition.

- Wyman, David S. (1984). The Abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

- Zander, Ulf (2015). "Dans l'œil de la tempête: la Suède et la Shoah". Revue d'Histoire de la Shoah (203): 277–290. doi:10.3917/rhsho.203.0277.

Further reading

[edit]- Wasserstein, Bernard (1999). Britain and the Jews of Europe, 1939-1945 (2nd ed.). London: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0718501587.

- Lánícek, Jan; Lambertz, Jan (2022). More than Parcels: Wartime Aid for Jews in Nazi-Era Camps and Ghettos. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-4924-3.

External links

[edit]Rabbi Eliezer Melamed, The Great Democracies' Disgrace on Arutz Sheva.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||