Head office in Beijing | |

Native name | 国家开发银行 |

|---|---|

| Industry | Development finance |

| Founded | 1994 |

| Headquarters | Beijing |

Key people | Zhao Huan, Chairman |

| Products | Banking |

| Revenue | 681,795,000,000 renminbi (2018) |

| Owner | Government-owned |

Number of employees |

|

| Website | www |

| Simplified Chinese | 国家开发银行 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 國家開發銀行 | ||||||

| |||||||

China Development Bank (CDB) is a policy bank of China under the State Council. Established in 1994, it has been described as the engine that powers the national government's economic development policies.[2][3] It has raised funds for numerous large-scale infrastructure projects, including the Three Gorges Dam and the Shanghai Pudong International Airport.

The bank is the second-largest bond issuer in China after the Ministry of Finance. In 2009, it accounted for about a quarter of the country's yuan bonds and is the biggest foreign-currency lender. CDB debt is owned by local banks and treated as a risk-free asset under the proposed People's Republic of China capital adequacy rules (i.e. the same treatment as PRC government bonds).[3]

History

[edit]

The China Development Bank[4] (CDB) was established in March 1994 to provide development-oriented financing for high-priority government projects. It is under the direct jurisdiction of the State Council and the People's Central Government. At present, it has 35 branches across the country and one representative office.

The main objective as a state financial institution is to support the macroeconomic policies of the central government and to support national economic development and strategic structural changes in the economy.[5] The bank provides financing for national projects such as infrastructure development, basic industries, energy, and transportation.[6] Most of CDB's loans are for domestic projects, and it began lending for projects abroad in the early 2000s.[7]: 41

From 1994 to 1998, CDB's fundraising was subject to a higher degree of state control than in later periods.[7]: 32 In the 1990s, CDB facilitated the creation of China's interbank bond market.[7]: 9 Initially, the People's Bank of China (PBOC) required domestic financial institutions such as commercial banks to buy policy bank bonds.[7]: 32 At this stage, the PBOC usually set high yields and did not permit the apportioned bonds to be sold on the secondary market.[7]: 33 In February 1996, CDB began its first overseas bond issuance in Japan, followed a year later by an issuance in the United States.[7]: 34 Overseas issuance helped CDB diversify its funding sources.[7]: 34 Ultimately, the issuance of bonds allowed CDB to become a financially independent bank without the state's tax revenues.[7]: 9

In April 1998, former PBOC deputy governor Chen Yuan, the eldest son of Chen Yun, was appointed CDB's governor.[7]: 34 [8]: 63 Chen implemented reforms designed to increase CDB's autonomy by reducing state involvement in CDB's fundraising and lending.[7]: 34

From 1998 to 2008, CDB increased its fundraising autonomy and used an auction-based bond issuance mechanism to raise its funds.[7]: 32 In 1999, CDB offered China's first floating rate bond.[7]: 35

CDB plays a major role in alleviating infrastructure and energy bottlenecks in the Chinese economy. In 2003, CDB made loan arrangements for, or evaluated and underwrote, a total of 460 national debt projects and issued 246.8 billion yuan in loans. This accounted for 41% of its total investment. CDB's loans to the "bottleneck" investments that the government prioritizes amounted to 91% of its total loan count. It also issued a total of 357.5 billion yuan in loans to western areas and more than 174.2 billion yuan to old industrial bases in Northeast China. These loans substantially increased the economic growth and structural readjustments of the Chinese economy.[9]

In 2005 and 2006, CDB successfully issued two pilot Asset-Backed Securities[10] (ABS) products in the domestic China market. Along with other ABS products issued by China Construction Bank, CDB has created a foundation for a promising debt capital and structured finance market.[11][12]

China and Venezuela established the China-Venezuela Joint Fund in 2007, with the goal of offering capital funding for infrastructure projects in Venezuela which can be performed by Chinese companies.[7]: 98–99 CDB lent $4 billion to the fund and the Venezuelan Economic and Social Development Bank (BANDES) contributed $2 billion.[7]: 98

As part of China's response to the 2008 global financial crisis, emphasis on CDB's policy aspects increased and the state formalized its credit guarantee for CDB.[7]: 32 CDB was one of the financial agencies implementing China's stimulus plan and vastly increased its lending for infrastructure and industrial projects.[7]: 37–38

From 2009 to 2019, CDB has issued 1.6 trillion yuan in loans to more than 4,000 projects involving infrastructure, communications, transportation, and basic industries. The investments are spread along the Yellow River, and both south and north of the Yangtze River. CDB has been increasingly focusing on developing the western and northwestern provinces in China. This could help reduce the growing economic disparity in the western provinces, and it has the potential to revitalize the old industrial bases of northeast China.[13]

In 2010, CDB provided $30 billion in financing to Chinese solar power manufacturers.[14]: 1

At the end of 2010, CDB held US$687.8 billion in loans, more than twice the amount of the World Bank.[3]

After Chen left the governorship of CDB in 2013, the bank's institutional power decreased.[7]: 157

The next CDB governor, Hu Huaibang, removed CDB personnel to staff the bank with personnel loyal to himself.[7]: 158 Hu then leveraged his personal influence to approve large amounts of industrial loans which ultimately failed.[7]: 158 Hu was removed from office in 2018 on suspicion of corruption and he was sentenced to life in prison in 2021 for accepting bribes to approve projects that should not have passed CDB criteria.[7]: 158–159 Following these events, CDB became significantly more cautious in its financing decisions.[7]: 159

CDB is among the state entities which contribute to the China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, which was established in an effort to decrease China's reliance on foreign semiconductor companies.[15]: 274 The fund was established in 2014.[15]: 274

In 2015, China used its foreign exchange reserves to recapitalize CDB, which in turn empowered it to make significant foreign loans.[8]: 70

In early 2016, a paifang (Chinese-style gate) that stood in front of the CDB head office building in Beijing was demolished, in what was widely interpreted as a sign of loss of favor from the Chinese political leadership.[16]

In 2017, CDB provided RMB 130 billion to fund infrastructure and environmental upgrading in Xiong'an.[17]: 155

As of December 2018, outstanding loans to 11 provincial-level regions along the belt amounted to 3.85 trillion yuan (about 575 billion U.S. dollars), according to the CDB. New yuan loans to these regions reached 304.5 billion yuan last year, accounting for 48 percent of the bank's total new yuan loans. The funds mainly went to major projects in the fields of ecological protection and restoration, infrastructure connectivity, and industrial transformation and upgrading. The CDB will continue to support ecological protection and green development of the Yangtze River in 2019, said CDB Chairman Zhao Huan. China issued a development plan for the Yangtze River Economic Belt in September 2016 and a guideline for green development of the belt in 2017. The Yangtze River Economic Belt consists of nine provinces and two municipalities that cover roughly one-fifth of China's land. It has a population of 600 million and generates more than 40 percent of the country's GDP.[18]

In 2020, China joined the G20-led Debt Service Suspension Initiative, through which official bilateral creditors suspended debt repayments of 73 of the poorest debtor countries.[7]: 134 China did not include CDB loans as part of the initiative under the logic that CDB was a commercial lender rather than an official bilateral creditor.[7]: 135

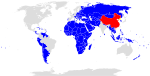

Along with the Silk Road Fund and the Export-Import Bank of China, the China Development Bank is one of the primary financing sources for Belt and Road Initiative projects in Africa,[19]: 245 and is an important funder of BRI projects more generally.[20]

Organizational structure

[edit]The Governors of the bank report to a Board of Supervisors, who are accountable to the central government. There are four vice governors and two assistant governors.[21] At the end of 2004, CDB had about 3,500 employees.[citation needed] About 1,000 of CDB's employees work at the Beijing Headquarters, with the rest in 35 mainland branches; including a representative office in Tibet and a branch in Hong Kong.[citation needed]}

As of 2021, the CDB has more than 9,000 employees.[1]

CDB does not accept deposits from individuals.[7]: 39 Its depositors are other financial agencies that are collaborating with CDB or entities which are repaying loans borrowed from CDB.[7]: 39

Ownership

[edit]CDB is wholly state-owned through multiple state bodies.[7]: 85 As of 2019, the owners were Central Huijin Investment Ltd. (one of China's sovereign funds), Buttonwood Investment Holding Company Ltd. (owned by the State Administration of Foreign Exchange), and the National Council for Social Security Fund.[7]: 85

Subsidiaries

[edit]Leadership

[edit]

CDB has a thirteen member board of directors.[7]: 84 Three are the executives in charge of managing CDB.[7]: 84 Six are directors from the agencies that hold shares of CDB.[7]: 84 The four "government-ministry directors" come from the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Commerce, and the People's Bank of China.[7]: 84

Highest ranking official

[edit]- Yao Zhenyan (1994-1998)[7]: 83

- Chen Yuan (1998-2013)[7]: 83

- Hu Huaibang (2013-2018)[7]: 83

- Zhao Huan (2018-present)[7]: 83

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "About China Development Bank 2021". www.cdb.com.cn. Archived from the original on 2016-06-22. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ^ CDB History Archived Archived 2005-07-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Michael Forsythe, Henry Sanderson (June 2011). "Financing China Costs Poised to Rise With CDB Losing Sovereign-Debt Status". Bloomberg Market Magazine.

- ^ "China Development Bank International Investment Limited - About Us". cdb-intl.com. Archived from the original on 2019-05-13. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ "China Development Bank International Investment Limited - Investor Relations". cdb-intl.com. Archived from the original on 2019-05-21. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ "China Development Bank International Investment Limited - Portfolio". cdb-intl.com. 2019-08-30. Archived from the original on 2019-05-17. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Chen, Muyang (2024). The Latecomer's Rise: Policy Banks and the Globalization of China's Development Finance. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501775857. JSTOR 10.7591/jj.6230186.

- ^ a b Liu, Zongyuan Zoe (2023). Sovereign Funds: How the Communist Party of China Finances its Global Ambitions. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. doi:10.2307/jj.2915805. ISBN 9780674271913. JSTOR jj.2915805. S2CID 259402050.

- ^ "Annual report" (PDF). www.cdb-intl.com. 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ "Handbook of China's Financial System1/61 Chapter 6: Bond MarketHandbook on China's Financial System" (PDF). www.zhiguohe.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ "Annual report" (PDF). www.cdb-intl.com. 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ "Annual report" (PDF). www.cdb-intl.com. 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

((cite web)): CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Lewis, Joanna I. (2023). Cooperating for the Climate: Learning from International Partnerships in China's Clean Energy Sector. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-54482-5.

- ^ a b Zhang, Angela Huyue (2024). High Wire: How China Regulates Big Tech and Governs Its Economy. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197682258.001.0001. ISBN 9780197682258.

- ^ Lucy Hornby & Yuan Yang (29 February 2016). "China Development Bank's landmark gate demolished". Financial Times.

- ^ Hu, Richard (2023). Reinventing the Chinese City. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-21101-7.

- ^ Wang, Ling; Lee, Shao-ju; Chen, Ping; Jiang, Xiao-mei; Liu, Bing-lian (2016-06-20). Contemporary Logistics in China: New Horizon and New Blueprint. Springer. p. 124. ISBN 9789811010521.

- ^ Murphy, Dawn (2022). China's Rise in the Global South: the Middle East, Africa, and Beijing's Alternative World Order. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-1-5036-3009-3.

- ^ Curtis, Simon; Klaus, Ian (2024). The Belt and Road City: Geopolitics, Urbanization, and China's Search for a New International Order. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 167. doi:10.2307/jj.11589102. ISBN 9780300266900. JSTOR jj.11589102.

- ^ China Development Bank

External links

[edit]| Central bank | |

|---|---|

| Policy bank | |

| State Council commercial | |

| Nationwide commercial | |

| Urban commercial | |

| Regulatory agency | |

| Corridors and projects (2019 Joint Communique) |

| ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linked to the BRI |

| ||||||||||||||

| Financial |

| ||||||||||||||

| Political |

| ||||||||||||||

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Other | |