Global disparities in regards to access to computing and information resources

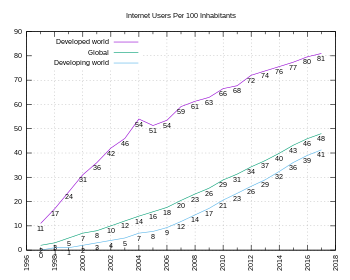

The global digital divide describes global disparities, primarily between developed and developing countries, in regards to access to computing and information resources such as the Internet and the opportunities derived from such access.[1]

The Internet is expanding very quickly, and not all countries—especially developing countries—can keep up with the constant changes.[example needed] The term "digital divide" does not necessarily mean that someone does not have technology; it could mean that there is simply a difference in technology. These differences can refer to, for example, high-quality computers, fast Internet, technical assistance, or telephone services.

Versus the digital divide

The global digital divide is a special case of the digital divide; the focus is set on the fact that "Internet has developed unevenly throughout the world"[14]: 681 causing some countries to fall behind in technology, education, labor, democracy, and tourism. The concept of the digital divide was originally popularized regarding the disparity in Internet access between rural and urban areas of the United States of America; the global digital divide mirrors this disparity on an international scale.

The global digital divide also contributes to the inequality of access to goods and services available through technology. Computers and the Internet provide users with improved education, which can lead to higher wages; the people living in nations with limited access are therefore disadvantaged.[15] This global divide is often characterized as falling along what is sometimes called the North–South divide of "northern" wealthier nations and "southern" poorer ones.

Obstacles to a solution

Some people argue that necessities need to be considered before achieving digital inclusion, such as an ample food supply and quality health care. Minimizing the global digital divide requires considering and addressing the following types of access:

Physical access

Involves "the distribution of ICT devices per capita…and land lines per thousands".[16]: 306 Individuals need to obtain access to computers, landlines, and networks in order to access the Internet. This access barrier is also addressed in Article 21 of the convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities by the United Nations.

Financial access

The cost of ICT devices, traffic, applications, technician and educator training, software, maintenance, and infrastructures require ongoing financial means.[17]

Financial access and "the levels of household income play a significant role in widening the gap" [18]

Socio-demographic access

Empirical tests have identified that several socio-demographic characteristics foster or limit ICT access and usage. Among different countries, educational levels and income are the most powerful explanatory variables, with age being a third one.[19][17]

While a Global Gender Gap in access and usage of ICT's exist, empirical evidence shows that this is due to unfavorable conditions concerning employment, education and income and not to technophobia or lower ability. In the contexts understudy, women with the prerequisites for access and usage turned out to be more active users of digital tools than men.[20] In the US, for example, the figures for 2018 show 89% of men and 88% of women use the Internet.[21]

Cognitive access

In order to use computer technology, a certain level of information literacy is needed. Further challenges include information overload and the ability to find and use reliable information.

Design access

Computers need to be accessible to individuals with different learning and physical abilities including complying with Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act as amended by the Workforce Investment Act of 1998 in the United States.[22]

Institutional access

In illustrating institutional access, Wilson states "the numbers of users are greatly affected by whether access is offered only through individual homes or whether it is offered through schools, community centers, religious institutions, cybercafés, or post offices, especially in poor countries where computer access at work or home is highly limited".[16]: 303

Political access

Guillen & Suarez argue that "democratic political regimes enable faster growth of the Internet than authoritarian or totalitarian regimes."[14]: 687 The Internet is considered a form of e-democracy, and attempting to control what citizens can or cannot view is in contradiction to this. Recently situations in Iran and China have denied people the ability to access certain websites and disseminate information. Iran has prohibited the use of high-speed Internet in the country and has removed many satellite dishes in order to prevent the influence of Western culture, such as music and television.[23]

Cultural access

Many experts claim that bridging the digital divide is not sufficient and that the images and language needed to be conveyed in a language and images that can be read across different cultural lines.[24] A 2013 study conducted by Pew Research Center noted how participants taking the survey in Spanish were nearly twice as likely not to use the internet.[25]

Proposed remedies

There are four specific arguments why it is important to "bridge the gap":[27]

- Economic equality – For example, the telephone is often seen as one of the most important components, because having access to a working telephone can lead to higher safety. If there were to be an emergency, one could easily call for help if one could use a nearby phone. In another example, many work-related tasks are online, and people without access to the Internet may not be able to complete work up to company standards. The Internet is regarded by some as a basic component of civic life that developed countries ought to guarantee for their citizens. Additionally, welfare services, for example, are sometimes offered via the Internet.[27]

- Social mobility – Computer and Internet use is regarded as being very important to development and success. However, some children are not getting as much technical education as others, because lower socioeconomic areas cannot afford to provide schools with computer facilities. For this reason, some kids are being separated and not receiving the same chance as others to be successful.[27]

- Democracy – Some people believe that eliminating the digital divide would help countries become healthier democracies. They argue that communities would become much more involved in events such as elections or decision making.[28][27]

- Economic growth – It is believed that less-developed nations could gain quick access to economic growth if the information infrastructure were to be developed and well used. By improving the latest technologies, certain countries and industries can gain a competitive advantage.[27]

While these four arguments are meant to lead to a solution to the digital divide, there are a couple of other components that need to be considered. The first one is rural living versus suburban living. Rural areas used to have very minimal access to the Internet, for example. However, nowadays, power lines and satellites are used to increase the availability in these areas. Another component to keep in mind is disabilities. Some people may have the highest quality technologies, but a disability they have may keep them from using these technologies to their fullest extent.[27]

Using previous studies (Gamos, 2003; Nsengiyuma & Stork, 2005; Harwit, 2004 as cited in James), James asserts that in developing countries, "internet use has taken place overwhelmingly among the upper-income, educated, and urban segments" largely due to the high literacy rates of this sector of the population.[29]: 58 As such, James suggests that part of the solution requires that developing countries first build up the literacy/language skills, computer literacy, and technical competence that low-income and rural populations need in order to make use of ICT.

It has also been suggested that there is a correlation between democrat regimes and the growth of the Internet. One hypothesis by Gullen is, "The more democratic the polity, the greater the Internet use...The government can try to control the Internet by monopolizing control" and Norris et al. also contends, "If there is less government control of it, the Internet flourishes, and it is associated with greater democracy and civil liberties.[30]

From an economic perspective, Pick and Azari state that "in developing nations…foreign direct investment (FDI), primary education, educational investment, access to education, and government prioritization of ICT as all-important".[30]: 112 Specific remedies proposed by the study include: "invest in stimulating, attracting, and growing creative technical and scientific workforce; increase the access to education and digital literacy; reduce the gender divide and empower women to participate in the ICT workforce; emphasize investing in intensive Research and Development for selected metropolitan areas and regions within nations".[30]: 111

There are projects worldwide that have implemented, to various degrees, the remedies outlined above. Many such projects have taken the form of Information Communications Technology Centers (ICT centers). Rahnman explains that "the main role of ICT intermediaries is defined as an organization providing effective support to local communities in the use and adaptation of technology. Most commonly, an ICT intermediary will be a specialized organization from outside the community, such as a non-governmental organization, local government, or international donor. On the other hand, a social intermediary is defined as a local institution from within the community, such as a community-based organization.[31]: 128

Other proposed remedies that the Internet promises for developing countries are the provision of efficient communications within and among developing countries so that citizens worldwide can effectively help each other to solve their problems. Grameen Banks and Kiva loans are two microcredit systems designed to help citizens worldwide to contribute online towards entrepreneurship in developing communities. Economic opportunities range from entrepreneurs who can afford the hardware and broadband access required to maintain Internet cafés to agribusinesses having control over the seeds they plant.

At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the IMARA organization (from Swahili word for "power") sponsors a variety of outreach programs which bridge the Global Digital Divide. Its aim is to find and implement long-term, sustainable remedies which will increase the availability of educational technology and resources to domestic and international communities. These projects are run under the aegis of the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) and staffed by MIT volunteers who give training, install and donate computer setups in greater Boston, Massachusetts, Kenya, Indian reservations the American Southwest such as the Navajo Nation, the Middle East, and Fiji Islands. The CommuniTech project strives to empower underserved communities through sustainable technology and education.[32][33][34] According to Dominik Hartmann of the MIT's Media Lab, interdisciplinary approaches are needed to bridge the global digital divide.[35]

Building on the premise that any effective solution must be decentralized, allowing the local communities in developing nations to generate their content, one scholar has posited that social media—like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter—may be useful tools in closing the divide.[36] As Amir Hatem Ali suggests, "the popularity and generative nature of social media empower individuals to combat some of the main obstacles to bridging the digital divide".[36]: 188 Facebook's statistics reinforce this claim. According to Facebook, more than seventy-five percent of its users reside outside of the US.[37] Moreover, more than seventy languages are presented on its website.[37] The reasons for the high number of international users are due to many the qualities of Facebook and other social media. Amongst them, are its ability to offer a means of interacting with others, user-friendly features, and the fact that most sites are available at no cost.[36] The problem with social media, however, is that it can be accessible, provided that there is physical access.[36] Nevertheless, with its ability to encourage digital inclusion, social media can be used as a tool to bridge the global digital divide.[36]

Some cities in the world have started programs to bridge the digital divide for their residents, school children, students, parents and the elderly. One such program, founded in 1996, was sponsored by the city of Boston and called the Boston Digital Bridge Foundation.[38] It especially concentrates on school children and their parents, helping to make both equally and similarly knowledgeable about computers, using application programs, and navigating the Internet.[39][40]

Free Basics

Free Basics is a partnership between social networking services company Facebook and six companies (Samsung, Ericsson, MediaTek, Opera Software, Nokia and Qualcomm) that plans to bring affordable access to selected Internet services to less developed countries by increasing efficiency, and facilitating the development of new business models around the provision of Internet access. In the whitepaper realised by Facebook's founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg,[41] connectivity is asserted as a "human right", and Internet.org is created to improve Internet access for people around the world.

"Free Basics provides people with access to useful services on their mobile phones in markets where internet access may be less affordable. The websites are available for free without data charges, and include content about news, employment, health, education and local information etc. By introducing people to the benefits of the internet through these websites, we hope to bring more people online and help improve their lives."[42]

However, Free Basics is also accused of violating net neutrality for limiting access to handpicked services. Despite a wide deployment in numerous countries, it has been met with heavy resistance notably in India where the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India eventually banned it in 2016.

Satellite constellations

Several projects to bring internet to the entire world with a satellite constellation have been devised in the last decade, one of these being Starlink by Elon Musk's company SpaceX. Unlike Free Basics, it would provide people with a full internet access and would not be limited to a few selected services. In the same week Starlink was announced, serial-entrepreneur Richard Branson announced his own project OneWeb, a similar constellation with approximately 700 satellites that was already procured communication frequency licenses for their broadcast spectrum and could possibly be operational on 2020.[43]

The biggest hurdle to these projects is the astronomical, financial, and logistical cost of launching so many satellites. After the failure of previous satellite-to-consumer space ventures, satellite industry consultant Roger Rusch said "It's highly unlikely that you can make a successful business out of this." Musk has publicly acknowledged this business reality, and indicated in mid-2015 that while endeavoring to develop this technically-complicated space-based communication system he wants to avoid overextending the company and stated that they are being measured in the pace of development.

As of 2023, Starlink is being actively deployed with the goal to clear licensure hurdles in every country open to its services.

One Laptop per Child

One Laptop per Child (OLPC) was an attempt by an American non-profit to narrow the digital divide.[44] This organization, founded in 2005, provided inexpensively produced "XO" laptops (dubbed the "$100 laptop", though actual production costs vary) to children residing in poor and isolated regions within developing countries. Each laptop belonged to an individual child and provides a gateway to digital learning and Internet access. The XO laptops were designed to withstand more abuse than higher-end machines, and they contained features in context to the unique conditions that remote villages present. Each laptop was constructed to use as little power as possible, had a sunlight-readable screen, and was capable of automatically networking with other XO laptops in order to access the Internet—as many as 500 machines can share a single point of access.[44] The project went defunct in 2014.