Civil rights movement in Nashville, Tennessee

The Nashville Student Movement was an organization that challenged racial segregation in Nashville, Tennessee, during the Civil Rights Movement. It was created during workshops in nonviolence taught by James Lawson. The students from this organization initiated the Nashville sit-ins in 1960. They were regarded as the most disciplined and effective of the student movement participants during 1960.[1] The Nashville Student Movement was key in establishing leadership in the Freedom Riders.[2]

Members of the Nashville Student Movement, who went on to lead many of the activities and create and direct many of the strategies of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, included Diane Nash, Bernard Lafayette, James Bevel, John Lewis, C. T. Vivian, Jim Zwerg, and others.[3][4]

Protesters intentionally dressed 'sharp' during protests in anticipation of their arrests.[5]

Prominent figures of the Civil Rights Movement, such as Martin Luther King Jr., recognized the brilliance of the Nashville Student Movement. King praised the individuals of this movement for their amazingly organized and highly disciplined attitudes.[6] The Nashville Student Movement, using Gandhian methods, shone a light on the proficiency of these nonviolent methods, which ultimately allowed for the 1960s movements to have the success they had. Nonviolent methods and tactics allowed for the message to travel further and led to the Nashville Student movement becoming a pillar of success during the age of the Civil Rights Movement.[7] An impressive accomplishment achieved by the actions of the Nashville Student Movement, was the ending of segregation in Nashville.[8] This helped Nashville lead the way for desegregation in the United States and acted as an example for other American cities to follow. Lawson, a vitally important member of the movement, served as an effective mentor for the younger generation, and using his knowledge of nonviolence which he gained by religious practices he helped others use pacifism as a method for ending Jim Crow laws.[9]

Response

The Nashville Student Movement received praise from Civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.[10]

Legacy

The Children, a 1999 book by David Halberstam, chronicles the participants and actions of the Nashville students.[11][12][13]

The establishment of the Nashville Student Movement was covered in John Lewis' 2013 graphic novel March: Book One and its animated series adaptation.[14][15]

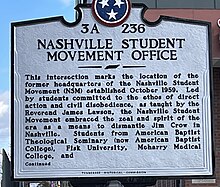

A marker called the "Nashville Student Movement Office" was placed at 21st Avenue North and Jefferson Street to commemorate the civil rights protests in Nashville.[16]

Tourism officials in Nashville and Tennessee overall have made efforts to make the civil rights movement in Nashville as a historical tourist attraction. Efforts began in January 2018, and six Nashville locations were made a part of the U.S. Civil Rights Trail across various Southern states, a collection of different Civil Rights locations.[17]

Nashville became an important site for civil rights activism because of the segregation and racial discrimination that continued in that city. The south was a notorious location for racism and white supremacy, as the demographic was predominately white compared to African Americans. Within Nashville there were four known colleges, which today are known as HBCUs (Historical Black Colleges & Universities). The students that attended these universities experienced various forms of discrimination outside on the streets of Nashville. Many of them decided to stand up and join together to for their rights. These students joined alongside Reverend James Lawson (activist), who orchestrated lessons on nonviolence. A majority of these lessons took place at Clark Memorial United Methodist Church on 14th Avenue North. Even one of the participants from the organization stated, "Clark was the birthplace of the civil rights movement in Nashville." Proceeding with the sit-ins, on the morning of February 27, 82 of the activists were arrested and trailed together on the same day. Of the 82 participants 77 were black students and five were white students. The mass arrests made the court only give them a choice between jail time and paying a fine. The racism that many African Americans had encountered in their daily life was what many had considered to be the cultural leftovers from history. After much success from other historical civil rights movements such as Brown v. Board of Education, Louisiana bus boycott, and the Alabama bus boycott, segregation and racism continued. The Nashville Student Movement tried using the Gandhian approach to nonviolent protests to bring an end to legal segregation in the South.