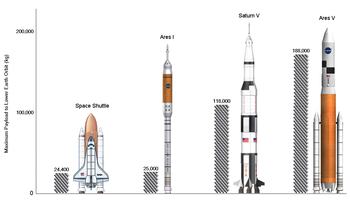

Super heavy-lift launch vehicles, to scale

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Super heavy-lift launch vehicle |

| Preceded by | Heavy-lift launch vehicle |

| Built | Since 1967 |

| General characteristics | |

| Capacity |

|

A super heavy-lift launch vehicle is a rocket that can lift to low Earth orbit a "super heavy payload", which is defined as more than 50 metric tons (110,000 lb)[1][2] by the United States and as more than 100 metric tons (220,000 lb) by Russia.[3] It is the most capable launch vehicle classification by mass to orbit, exceeding that of the heavy-lift launch vehicle classification.

Only 14 such payloads were successfully launched before 2022: 12 as part of the Apollo program before 1972 and two Energia launches, in 1987 and 1988. Most planned crewed lunar and interplanetary missions depend on these launch vehicles.

Several super heavy-lift launch vehicle concepts were produced in the 1960s,[4] including the Sea Dragon. During the Space Race, the Saturn V and N1 were built by the United States and Soviet Union, respectively. After the Saturn V's successful Apollo program and the N1's failures, the Soviets' Energia launched twice in the 1980s, once bearing the Buran spaceplane. The next two decades saw multiple concepts drawn out once again, most notably Space Shuttle-derived vehicles and Rus-M, but none were built. In the 2010s, super heavy-lift launch vehicles received interest once again, leading to the launch of the Falcon Heavy, the Space Launch System, and Starship, and the beginning of development of the Long March and Yenisei rockets.

Flown vehicles

[edit]Retired

[edit]- Saturn V was a NASA launch vehicle that made 13 orbital launches between 1967 and 1973, principally for the Apollo program through 1972. The Apollo lunar payload included a command module, service module, and Lunar Module, with a total mass of 45 t (99,000 lb).[5][6] When the third stage and Earth-orbit departure fuel was included, Saturn V placed approximately 140 t (310,000 lb) into low Earth orbit.[7] The final launch of Saturn V in 1973 placed Skylab, a 77-tonne (170,000 lb) payload, into LEO.

- The Energia launcher was designed by the Soviet Union to launch up to 105 t (231,000 lb) to low Earth orbit.[8] Energia launched twice in 1987/88 before the program was cancelled by the Russian government, which succeeded the Soviet Union, but only the second flight payload reached orbit. On the first flight, launching the Polyus weapons platform (approximately 80 t (180,000 lb)), the vehicle failed to enter orbit due to a software error on the kick-stage.[8] The second flight successfully launched the Buran orbiter.[9] Buran was intended to be reusable, similar to the Space Shuttle Orbiter, but it relied entirely on the disposable launcher Energia to reach orbit.

Operational

[edit]- Falcon Heavy is rated to launch 63.8 t (141,000 lb) to low Earth orbit (LEO) in a fully expendable configuration and an estimated 57 t (126,000 lb) in a partially reusable configuration, in which only two of its three boosters are recovered.[10][11][a] The latter configuration flew on 1 November 2022,[13] but with a much smaller ~3,700 kg (8,200 lb) payload being launched to geostationary orbit with maximum of ~9,200 kg (20,300 lb) payload being launched to geostationary orbit on 29 July 2023 on the rocket's seventh overall flight. The fully expendable configuration flew only once on 1 May 2023, but with a much smaller ~6,722 kg (14,819 lb) payload being launched to geostationary orbit. The first test flight occurred on 6 February 2018, in a configuration in which recovery of all three boosters was attempted, with Elon Musk's Tesla Roadster of 1,250 kg (2,760 lb) sent to an orbit beyond Mars.[14][15][16]

- The Space Launch System (SLS) is a US government super heavy-lift expendable launch vehicle developed by NASA and launched its first mission on 16 November 2022. It is slated to be the primary launch vehicle for NASA's deep space exploration plans,[17][18] including the planned crewed lunar flights of the Artemis program and a possible follow-on human mission to Mars in the 2030s.[19][20][21]

Under development

[edit]- The SpaceX Starship system is a two-stage-to-orbit fully reusable launch vehicle being privately developed by SpaceX, consisting of the Super Heavy booster as the first stage and a second stage, also called Starship.[22][23] It is designed to be a long-duration cargo and passenger-carrying spacecraft.[24] After two failed flight tests,[25][26] Starship completed its first successful launch on its third flight on March 14, 2024,[27] and achieved soft landing of both stages on its fourth flight.[28]

- The Long March 9 is a Chinese three-stage-to-orbit partially reusable launch vehicle currently being developed by the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology. The design has undergone numerous major changes over the years and with the most recent designs showing some resemblance to the SpaceX Starship. The Long March 9 is planned to be operational by the early 2030s.[29]

- The Long March 10 is a Chinese three-stage-to-orbit partially reusable launch vehicle currently being developed by the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology with an initial launch targeting the 2025–2027 time range.

Unsuccessfully flown

[edit]- The N1 was a three-stage super heavy lift launch vehicle developed in the Soviet Union from 1965 to 1974. It was the Soviet counterpart to the Saturn V, however all four test flights of the vehicle ended in flight failure. For lunar missions, it would carry the L3 crewed lunar payload into Low Earth Orbit, which had an additional two stages, a Soyuz 7K-LOK as a mothership and an LK lunar lander that would be used for crewed lunar landings. Its Block A first stage held the record for the most thrust of any rocket stage built until it was superseded by the Super Heavy booster on its first flight.

Comparison

[edit]| Rocket | Configuration | Organization | Nationality | Human rated | Max First Stage Thrust | Mass to LEO | Maiden successful orbital flight | First >50 t payload | Status | Reusable | Launches (success / total) |

Launch cost | Launch cost (2020, US$ in millions) |

Cost / t (2020, US$ in millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturn V | Apollo/Skylab | NASA | Yes | 34,500 kN (7,750,000 lbf) |

140 t (310,000 lb)A | 1967 | 1967 | Retired (1973) |

No | 12G / 13 | US$1.23 billion (2019) | US$1,245 | $8.9 | |

| N1 | OKB-1 | Not achieved | 45,400 kN (10,200,000 lbf) |

95 t (209,000 lb) | none | none | Cancelled (1974) | No | 0 / 4 | 3 billion |

US$1,500[30] | $16 | ||

| Energia | NPO Energia | Not achieved | 34,800 kN (7,800,000 lbf) |

100 t (220,000 lb)B | (1987) | (1987) | Retired (1988) |

No | 2 / 2 | US$764 million (1985) | US$1,838 | $18 | ||

| Falcon Heavy | Recoverable Side Boosters | SpaceX | No | 22,800 kN (5,100,000 lbf) |

57 t (126,000 lb)[10] | 2022 | Not yet | Operational but mass untested | Partially | 5 / 5 F | US$90 million (2018) | US$92 | $1.6 | |

| Expended | No | 63.8 t (141,000 lb)[31] | 2023 | Not yet | Operational but mass untested | No | 1 / 1 F | US$150 million (2018) | US$154 | $2.4 | ||||

| SLS | Block 1 | NASA | Yes | 39,000 kN (8,800,000 lbf) |

95 t (209,000 lb)[32]D | 2022 | 2022 | Operational | No | 1 / 1 | US$2.2 billion (2021) | US$2,100 | 22.1 | |

| Block 1B | Planned | 105 t (231,000 lb)[33] | Planned (2028) | — | Under development | No | — | ? | ? | ? | ||||

| Block 2 | Planned | 41,000 kN (9,200,000 lbf) |

130 t (290,000 lb)[34] | Planned (2031) | — | Under development | No | — | ? | ? | ? | |||

| Starship | V1 | SpaceX | No | 69.9 MN (15,700,000 lbf)[35] | 100 t (220,000 lb)[36]E | Planned (2024) | Not yet | Flight Testing | No | 2 / 4 | Project US$<90 million (2024)[37]I | US$<75 | $<0.75 | |

| V2 | Unknown | 80.8 MN (18,200,000 lbf)[35] | 150 t (330,000 lb)[36]E | Planned (2024) | — | Under development | Fully | — | Projected US$<10 million (2024)[37]I | US$<8.4 | $<0.056 | |||

| V3 | Planned | 98 MN (22,000,000 lbf)[35] | 200 t (440,000 lb)[38]E | TBA | — | Under development | Fully | — | Projected US$<6 million (2024)[38] | US$<5 | $<0.025 | |||

| Long March 10 | CALT | Planned | 26,250 kN (5,900,000 lbf) |

70 t (150,000 lb)[39] | Planned (2027) | — | Under development | No | — | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Long March 9 | CALT | Planned | 60,000 kN (13,490,000 lbf) |

150 t (330,000 lb)[40] | Planned (2033) | — | Under development | Partially | — | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Yenisei | Yenisei | Progress | Planned | 43,500 kN (9,780,000 lbf) |

103 t (227,000 lb) | TBA | — | Under development | No | — | ? | ? | ? | |

| Don | Planned | 130 t (290,000 lb) | TBA | — | Under development | No | — | ? | ? | ? | ||||

^A Includes mass of Apollo command and service modules, Apollo Lunar Module, Spacecraft/LM Adapter, Saturn V Instrument Unit, S-IVB stage, and propellant for translunar injection; payload mass to LEO is about 122.4 t (270,000 lb)[41]

^B Required upper stage or payload to perform final orbital insertion

^C Side booster cores recoverable, center core intentionally expended. First re-use of the side boosters was demonstrated in 2019 when the ones used on the Arabsat-6A launch were reused on the STP-2 launch.

^D Includes mass of Orion spacecraft, European Service Module, Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage, and propellant for translunar injection

^E Does not include dry mass of spaceship

^F Falcon Heavy has launched 9 times since 2018, but first three times did not qualify as a "super heavy" because recovery of the center core was attempted.

^G Apollo 6 was a "partial failure": It reached orbit, but had problems with the second and third stages.

^I Estimate by third party

Proposed designs

[edit]Chinese proposals

[edit]Long March 10 was first proposed in 2018 as a concept for the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program.[42] Long March 9, an over 150 t (330,000 lb) to LEO capable rocket was proposed in 2018[43] by China, with plans to launch the rocket by 2028. The length of the Long March-9 will exceed 114 meters, and the rocket would have a core stage with a diameter of 10 meters. Long March 9 is expected to carry a payload of over 150 tonnes into low-Earth orbit, with a capacity of over 50 tonnes for Earth-Moon transfer orbit.[44][45] Development was approved in 2021.[46]

Russian proposals

[edit]Yenisei,[47] a super heavy-lift launch vehicle using existing components instead of pushing the less-powerful Angara A5V project, was proposed by Russia's RSC Energia in August 2016.[48]

A revival of the Energia booster was proposed in 2016, also to avoid pushing the Angara project.[49] If developed, this vehicle could allow Russia to launch missions towards establishing a permanent Moon base with simpler logistics, launching just one or two 80-to-160-tonne super-heavy rockets instead of four 40-tonne Angara A5Vs implying quick-sequence launches and multiple in-orbit rendezvous. In February 2018, the КРК СТК (space rocket complex of the super-heavy class) design was updated to lift at least 90 tonnes to LEO and 20 tonnes to lunar polar orbit, and to be launched from Vostochny Cosmodrome.[50] The first flight is scheduled for 2028, with Moon landings starting in 2030.[51] It looks like this proposal has been at least paused.[52]

US proposals

[edit]Blue Origin has plans for a project following their New Glenn rocket, termed New Armstrong, which some media sources have speculated will be a larger launch vehicle.[53]

Cancelled designs

[edit]

Numerous super-heavy-lift vehicles have been proposed and received various levels of development prior to their cancellation.

As part of the Soviet crewed lunar project to compete with Apollo/Saturn V, the N1 rocket was secretly designed with a payload capacity of 95 t (209,000 lb). Four test vehicles were launched from 1969 to 1972, but all failed shortly after lift-off.[54] The program was suspended in May 1974 and formally cancelled in March 1976.[55][56] The Soviet UR-700 rocket design concept competed against the N1, but was never developed. In the concept, it was to have had a payload capacity of up to 151 t (333,000 lb)[57] to low earth orbit.

During project Aelita (1969–1972), the Soviets were developing a way to beat the Americans to Mars. They designed the UR-700A, a nuclear powered variant of the UR-700, and UR-700M, a LOx/Kerosene variant to assemble the 1,400 t (3,100,000 lb) MK-700 spacecraft in earth orbit in two launches. The UR-700M would have a payload capacity of 750 t (1,650,000 lb).[58] The only Universal Rocket to make it past the design phase was the UR-500 while the N1 was selected to be the Soviets' HLV for lunar and Martian missions.[59]

The UR-900, proposed in 1969, would have had a payload capacity of 240 t (530,000 lb) to low earth orbit. It never left the drawing board.[60]

The General Dynamics Nexus was proposed in the 1960s as a fully reusable successor to the Saturn V rocket, having the capacity of transporting up to 450–910 t (990,000–2,000,000 lb) to orbit.[61][62]

The American Saturn MLV family of rockets was proposed in 1965 by NASA as successors to the Saturn V rocket.[63] It would have been able to carry up to 160,880 kg (354,680 lb) to low Earth orbit. The Nova designs were also studied by NASA before the agency chose the Saturn V in the early 1960s.[64]

Based on the recommendations of the Stafford Synthesis report, First Lunar Outpost (FLO) would have relied on a massive Saturn-derived launch vehicle known as the Comet HLLV. The Comet would have been capable of injecting 230.8 t (508,800 lb) into low earth orbit and 88.5 t (195,200 lb) on a TLI making it one of the most capable vehicles ever designed.[65] FLO was cancelled during the design process along with the rest of the Space Exploration Initiative.[citation needed]

The U.S. Ares V for the Constellation program was intended to reuse many elements of the Space Shuttle program, both on the ground and flight hardware, to save costs. The Ares V was designed to carry 188 t (414,000 lb) and was cancelled in 2010.[66]

The Shuttle-Derived Heavy Lift Launch Vehicle ("HLV") was an alternate super heavy-lift launch vehicle proposal for the NASA Constellation program, proposed in 2009.[67]

A 1962 design proposal, Sea Dragon, called for an enormous 150 m (490 ft) tall, sea-launched rocket capable of lifting 550 t (1,210,000 lb) to low Earth orbit. Although preliminary engineering of the design was done by TRW, the project never moved forward due to the closing of NASA's Future Projects Branch.[68][69]

The Rus-M was a proposed Russian family of launchers whose development began in 2009. It would have had two super heavy variants: one able to lift 50–60 tons, and another able to lift 130–150 tons.[70]

SpaceX Interplanetary Transport System was a 12 m (39 ft) diameter launch vehicle concept unveiled in 2016. The payload capability was to be 550 t (1,210,000 lb) in an expendable configuration or 300 t (660,000 lb) in a reusable configuration.[71] In 2017, the 12 m evolved into a 9 m (30 ft) diameter concept Big Falcon Rocket, which became the SpaceX Starship.[72]

See also

[edit]- Comparison of orbital launch systems

- List of orbital launch systems

- Sounding rocket, suborbital launch vehicle

- Small-lift launch vehicle, capable of lifting up to 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) to low Earth orbit

- Medium-lift launch vehicle, capable of lifting 2,000 to 20,000 kg (4,400 to 44,000 lb) of payload into low Earth orbit

- Heavy-lift launch vehicle, capable of lifting 20,000 to 50,000 kg (44,000 to 110,000 lb) of payload into low Earth orbit

Notes

[edit]- ^ A configuration in which all three cores are intended to be recoverable is classified as a heavy-lift launch vehicle since its maximum possible payload to LEO is under 50,000 kg.[12][11]

References

[edit]- ^ McConnaughey, Paul K.; et al. (November 2010). "Draft Launch Propulsion Systems Roadmap: Technology Area 01" (PDF). NASA. Section 1.3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

Small: 0–2 t payloads; Medium: 2–20 t payloads; Heavy: 20–50 t payloads; Super Heavy: > 50 t payloads.

- ^ "Seeking a Human Spaceflight Program Worthy of a Great Nation" (PDF). Review of U.S. Human Spaceflight Plans Committee. NASA. October 2009. pp. 64–66. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

...the U.S. human spaceflight program will require a heavy-lift launcher ... in the range of 25 to 40 mt ... this strongly favors a minimum heavy-lift capacity of roughly 50 mt....

- ^ Osipov, Yury (2004–2017). Great Russian Encyclopedia. Moscow: Great Russian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ "The Enormous Sea-Launched Rocket That Never Flew". Popular Mechanics. 3 April 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ "Apollo 11 Lunar Module". NASA. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ "Apollo 11 Command and Service Module (CSM)". NASA. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ Alternatives for Future U.S. Space-Launch Capabilities (PDF), The Congress of the United States. Congressional Budget Office, October 2006, pp. X, 1, 4, 9, archived from the original on 1 October 2021, retrieved 16 March 2016

- ^ a b "Polyus". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 25 May 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ "Buran". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ a b Musk, Elon [@elonmusk] (12 February 2018). "Side boosters landing on droneships & center expended is only ~10% performance penalty vs fully expended. Cost is only slightly higher than an expended F9, so around $95M" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b "Capabilities & Services". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 15 January 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ Elon Musk [@elonmusk] (30 April 2016). "@elonmusk Max performance numbers are for expendable launches. Subtract 30% to 40% for reusable booster payload" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (4 October 2021). "Payload issue delays SpaceX's next Falcon Heavy launch to early 2022". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 31 May 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (6 February 2018). "Falcon Heavy, SpaceX's Big New Rocket, Succeeds in Its First Test Launch". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ "Tesla Roadster (AKA: Starman, 2018-017A)". ssd.jpl.nasa.gov. 1 March 2018. Archived from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ SMC [@AF_SMC] (18 June 2019). "The 3700 kg Integrated Payload Stack (IPS) for #STP2 has been completed! Have a look before it blasts off on the first #DoD Falcon Heavy launch! #SMC #SpaceStartsHere" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Siceloff, Steven (12 April 2015). "SLS Carries Deep Space Potential". Nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "World's Most Powerful Deep Space Rocket Set To Launch In 2018". Iflscience.com. 29 August 2014. Archived from the original on 1 September 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ Chiles, James R. "Bigger Than Saturn, Bound for Deep Space". Airspacemag.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Finally, some details about how NASA actually plans to get to Mars". Arstechnica.com. 28 March 2017. Archived from the original on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ Gebhardt, Chris (6 April 2017). "NASA finally sets goals, missions for SLS – eyes multi-step plan to Mars". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ Berger, Eric (29 September 2019). "Elon Musk, Man of Steel, reveals his stainless Starship". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ "Starship". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 30 September 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ Lawler, Richard (20 November 2018). "SpaceX BFR has a new name: Starship". Engadget. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ Therrien, Alex; Whitehead, Jamie (20 April 2023). "SpaceX Starship live: SpaceX Starship finally launches but blows up after take-off". BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ Wattles, Jackie (18 November 2023). "Live updates: SpaceX Starship rocket lost in second test flight". CNN. Archived from the original on 18 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ^ Weber, Ryan (13 March 2024). "Starship Flight 3 Excels through most Major Milestones". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ "SpaceX soars through new milestones in test flight of the most powerful rocket ever built". 6 June 2024. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ Beil, Adrian (28 April 2023). "How Chang Zheng 9 arrived at the "Starship-like" design". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ "N1 1964". Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022. (adjusted for inflation since 1985)

- ^ "Falcon Heavy". SpaceX. 16 November 2012. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ Harbaugh, Jennifer, ed. (9 July 2018). "The Great Escape: SLS Provides Power for Missions to the Moon". NASA. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ "Space Launch System" (PDF). NASA Facts. NASA. 11 October 2017. FS-2017-09-92-MSFC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Creech, Stephen (April 2014). "NASA's Space Launch System: A Capability for Deep Space Exploration" (PDF). NASA. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ a b c Elon Reveals Starship Version 3; We Have Questions!. Retrieved 17 April 2024 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ a b "SpaceX – Starship". SpaceX. 17 April 2024. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ a b Smith, Rich (11 February 2024). "The Secret to SpaceX's $10 Million Starship, and How SpaceX Will Dominate Space for Years to Come". The Motley Fool. Archived from the original on 12 February 2024. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ a b Berger, Eric (8 April 2024). "Elon Musk just gave another Mars speech—this time the vision seems tangible". Ars Technica. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ Xin, Ling (30 April 2024). "China's most powerful space engine configuration is 'ready for flight'". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ Beil, Adrian (3 March 2023). "Starship debut leading the rocket industry toward full reusability". NASASpaceflight.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Yes, NASA's New Megarocket Will be More Powerful Than the Saturn V". Space.com. 16 August 2016. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ "China is building a new rocket to fly its astronauts on the moon". Space.com. October 2020. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ "China reveals details for super-heavy-lift Long March 9 and reusable Long March 8 rockets". 5 July 2018. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Xuequan, Mu (19 September 2018). "China to launch Long March-9 rocket in 2028". Xinhua. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018.

- ^ 盧伯華 (1 December 2022). "頭條揭密》中國版星艦2030首飛 陸長征9號超重型火箭定案" (in Traditional Chinese). 中国新闻网. Archived from the original on 3 May 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ Berger, Eric (24 February 2021). "China officially plans to move ahead with super-heavy Long March 9 rocket". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly (19 February 2019). "The Yenisei super-heavy rocket". RussianSpaceWeb. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ ""Роскосмос" создаст новую сверхтяжелую ракету". Izvestia (in Russian). 22 August 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ "Роскосмос" создаст новую сверхтяжелую ракету. Izvestia (in Russian). 22 August 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ "РКК "Энергия" стала головным разработчиком сверхтяжелой ракеты-носителя" [RSC Energia is the lead developer of the super-heavy carrier rocket]. RIA.ru. RIA Novosti. 2 February 2018. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly (8 February 2019). "Russia Is Now Working on a Super Heavy Rocket of Its Own". Popular Mechanics. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Better late than never: why the development of the Yenisei launch vehicle was stopped". 17 September 2021. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ "Blue Origin's huge new rocket has a nose cone bigger than its current rocket". Cnet. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "N1 Moon Rocket". Russianspaceweb.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ Harvey, Brian (2007). Soviet and Russian Lunar Exploration. Springer-Praxis Books in Space Exploration. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-387-21896-0. Archived from the original on 24 February 2024. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ van Pelt, Michel (2017). Dream Missions: Space Colonies, Nuclear Spacecraft and Other Possibilities. Springer-Praxis Books in Space Exploration. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 22. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-53941-6. ISBN 978-3-319-53939-3. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ "Russian UR-700 launch vehicle". astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "UR-700M". astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ "UR-700M". www.astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 8 October 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ "Russian UR-900 launch vehicle". astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ "SP-4221 The Space Shuttle Decision Chapter 2 NASA's Uncertain Future". NASA. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Nexus SSTO VTOVL launch vehicle". astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "Modified Launch Vehicle (MLV) Saturn V Improvement Study Composite Summary Report". NASA NTRS. 2 July 1965. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Teitel, Amy Shira (31 May 2019). "Nova: The Apollo rocket that never was". Astronomy Magazine. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "First Lunar Outpost". spacedaily.com. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "Ares". Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ "Shuttle-Derived Heavy Lift Launch Vehicle" (PDF). NASA. 17 June 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Grossman, David (3 April 2017). "The Enormous Sea-Launched Rocket That Never Flew". Popular Mechanics. Archived from the original on 30 November 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ “Study of Large Sea-Launch Space Vehicle,” Contract NAS8-2599, Space Technology Laboratories, Inc./Aerojet General Corporation Report #8659-6058-RU-000, Vol. 1 – Design, January 1963

- ^ "Rus-M launch vehicle". russianspaceweb.com. Archived from the original on 27 February 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "Making Humans a Multiplanetary Species" (PDF). SpaceX. 27 September 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (19 November 2018). "Goodbye, BFR … hello, Starship: Elon Musk gives a classic name to his Mars spaceship". GeekWire. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

Spaceflight lists and timelines | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | |||||||||||||||||

| Human spaceflight |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Solar System exploration | |||||||||||||||||

| Earth-orbiting satellites | |||||||||||||||||

| Vehicles | |||||||||||||||||

| Launches by rocket type |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Launches by spaceport | |||||||||||||||||

| Agencies, companies and facilities | |||||||||||||||||

| Other mission lists and timelines | |||||||||||||||||