Pallava dynasty | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 275 CE–897 CE | |||||||||||||||

![Pallava territories during Narasimhavarman I c. 645. This includes the Chalukya territories occupied by the Pallavas.[1]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c0/Pallava_territories.png/250px-Pallava_territories.png) Pallava territories during Narasimhavarman I c. 645. This includes the Chalukya territories occupied by the Pallavas.[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Dynasty | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Kanchipuram | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

• 275–300 | Simhavarman I | ||||||||||||||

• 885–897 | Aparajitavarman | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Classical India | ||||||||||||||

• Established | 275 CE | ||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 897 CE | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | India Sri Lanka[3] | ||||||||||||||

| Pallava Monarchs (200s–800s CE) | |

|---|---|

| Virakurcha | (??–??) |

| Vishnugopa I | (??–??) |

| Vishnugopa II | (??–??) |

| Simhavarman III | (??–??) |

| Simhavishnu | 575–600 |

| Mahendravarman I | 600–630 |

| Narasimhavarman I | 630–668 |

| Mahendravarman II | 668–670 |

| Paramesvaravarman I | 670–695 |

| Narasimhavarman II | 695–728 |

| Paramesvaravarman II | 728–731 |

| Nandivarman II | 731–795 |

| Dantivarman | 795–846 |

| Nandivarman III | 846–869 |

| Nrpatungavarman | 869–880 |

| Aparajitavarman | 880–897 |

The Pallava dynasty existed from 275 CE to 897 CE, ruling a significant portion of the Deccan, also known as Tondaimandalam. The Pallavas played a crucial role in shaping in particular southern Indian history and heritage.[4][5] The dynasty rose to prominence after the downfall of the Satavahana Empire, whom they had formerly served as feudatories.[6][7]

The Pallavas became a major southern Indian power during the reign of Mahendravarman I (600–630 CE) and Narasimhavarman I (630–668 CE), and dominated the southern Telugu region and the northern parts of the Tamil region for about 600 years, until the end of the 9th century. Throughout their reign, they remained in constant conflict with both the Chalukyas of Vatapi to the north, and the Tamil kingdoms of Chola and Pandyas to their south. The Pallavas were finally defeated by the Chola ruler Aditya I in the 9th century CE.[8]

The Pallavas are most noted for their patronage of Hindu Vaishnava temple architecture, the finest example being the Shore Temple, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Mamallapuram. Kancheepuram served as the capital of the Pallava kingdom. The dynasty left behind magnificent sculptures and temples, and are recognized to have established the foundations of medieval southern Indian architecture, which some scholars believe the ancient Hindu treatise Manasara inspired.[9] They developed the Pallava script, from which Grantha ultimately took form. This script eventually gave rise to several other Southeast Asian scripts such Khmer. The Chinese traveller Xuanzang visited Kanchipuram during Pallava rule and extolled their benign rule.

Etymology

[edit]The word Pallava means a creeper or branch in Sanskrit.[10][11][12] Pallava also means arrow or spruce in Tamil.[13][14][15]

Origins

[edit]

The origins of the Pallavas have been debated by scholars.[16] The available historical materials include three copper-plate grants of Sivaskandavarman in the first quarter of the 4th century CE, all issued from Kanchipuram but found in various parts of Andhra Pradesh, and another inscription of Simhavarman I half century earlier in the Palnadu (Pallava Nadu) area of the western Guntur district.[17][18] All the early documents are in Prakrit, and scholars find similarities in paleography and language with the Satavahanas and the Mauryas.[19] Their early coins are said to be similar to those of Satavahanas.[20] Two main theories regarding the origins of the Pallavas have emerged based on available historical data. The first theory suggests that the Pallavas were initially subordinate to the Satavahanas, a ruling dynasty in the Andhradesa region (north of the Penna River in modern-day Andhra Pradesh[21]). According to this theory, the Pallavas later expanded their influence southward, eventually establishing their power in Kanchi (modern-day Kanchipuram). The second theory proposes that the Pallavas originated in Kanchi itself, where they initially rose to prominence. From there, they expanded their dominion northward, reaching as far as the Krishna River. Another theory posits that the Pallavas were descendants of Chola Prince Ilandiraiyan and had their roots in Tondaimandalam, the region around Kanchi. These theories provide different perspectives on the Pallavas' early history and territorial expansion, but the exact origins of the Pallava dynasty continue to be a subject of debate among historians.

The proponents of the Andhra origin theory include S. Krishnaswami Aiyangar and K. A. Nilakanta Sastri. They believe that Pallavas were originally feudatories of the Satavahanas in the south-eastern part of their empire who became independent when the Satavahana power declined.[22] They are seen to be "strangers to the Tamil country", unrelated to the ancient lines of Cheras, Pandyas and Cholas. Since Simhavarman's grant bears no regal titles, they believe that he might have been a subsidiary to the Andhra Ikshvakus who were in power in Andhradesa at that time. In the following half-century, the Pallavas became independent and expanded up to Kanchi.[23][24]

S. Krishnaswami Aiyengar also speculates that the Pallavas were natives of Tondaimandalam and the name Pallava is identical with the word Tondaiyar.[25] Chola Prince Ilandiraiyan is traditionally regarded as the founder of the Pallava dynasty.[26] Ilandiraiyan is referred to in the literature of the Sangam period such as the Pathupattu. In the Sangam epic Manimekalai, he is depected as the son of Chola king Killi and the Naga princess Pilivalai, the daughter of king Valaivanan of Manipallavam.

Another theory is propounded by historians R. Sathianathaier[16] and D. C. Sircar,[27] with endorsements by Hermann Kulke, Dietmar Rothermund[28] and Burton Stein.[29] Sircar points out that the family legends of the Pallavas speak of an ancestor descending from Ashwatthama, the legendary warrior of Mahabharata, and his union with a Naga princess. According to Ptolemy, the Aruvanadu region between the northern and southern Penner rivers (Penna and Ponnaiyar[30][31]) was ruled by a king Basaronaga around 140 CE. By marrying into this Naga family, the Pallavas would have acquired control of the region near Kanchi.[27] While Sircar allows that Pallavas might have been provincial rulers under the later Satavahanas with a partial northern lineage, Sathianathaier sees them as natives of Tondaimandalam (the core region of Aruvanadu). He argues that they could well have adopted northern Indian practices under the Mauryan Asoka's rule. He relates the name "Pallava" to Pulindas, whose heritage is borne by names such as "Pulinadu" and "Puliyurkottam" in the region.[32]

According to Sir H. A. Stuart the Pallavas were Kurumbas and Kurubas their modern representatives.[33] This is supported by Marathi historian R. C. Dhere who stated that Pallavas were originally pastoralists that belonged to Kuruba lineages.[34] The territory of Pallavas was bordered by the Coromandel Coast along present Tamil Nadu and southern Andhra Pradesh. Out of the coins found here, the class of gold and silver coins belonging to the 2nd-7th century CE period contain the Pallava emblem, the maned lion, together with Kannada or Sanskrit inscription which showed that the Pallavas used Kannada too in their administration along with Prakrit, Sanskrit and Tamil.[35]

According to C. V. Vaidya, the Pallavas were Maharashtrian Aryans who spoke Maharashtri Prakrit for centuries and hence retained it even in the midst of surrounding Dravidian languages. They may even be said to have been 'Marathas' for their name was said to be still preserved in the Maratha family name of 'Pālave' (which is just Prakrit form of Pallava). And a further corroboration is that the gotra of the Pālave Maratha family is Bharadwaja, same as the one which Pallavas have attributed to themselves in their records.[36]

Overlaid on these theories is another hypothesis of Sathianathaier which claims that "Pallava" is a derivative of Pahlava (the Sanskrit term for Parthians). According to him, partial support for the theory can be derived from a crown shaped like an elephant's scalp depicted on some sculptures, which seems to resemble the crown of Demetrius I.[16]

Rivalries

[edit]With Cholas

[edit]The Pallavas captured Kanchi from the Cholas as recorded in the Velurpalaiyam Plates, around the reign of the fifth king of the Pallava line Kumaravishnu I.[citation needed] Thereafter Kanchi figures in inscriptions as the capital of the Pallavas. The Cholas drove the Pallavas away from Kanchi in the mid-4th century, in the reign of Vishnugopa, the tenth king of the Pallava line.[citation needed] The Pallavas re-captured Kanchi from the Kalabhras in the mid-6th century, [citation needed]possibly in the reign of Simhavishnu,[citation needed] the fourteenth king of the Pallava line, whom the Kasakudi plates state as "the lion of the earth". Thereafter the Pallavas held on to Kanchi until the 9th century, until the reign of their last king, Vijaya-Nripatungavarman.[39]

With Kadambas

[edit]The Pallavas were in conflict with major kingdoms at various periods of time. A contest for political supremacy existed between the early Pallavas and the Kadambas. Numerous Kadamba inscriptions provide details of Pallava-Kadamba hostilities.[40]

With Kalabhras

[edit]During the reign of Vishnugopavarman II (approx. 500–525), political convulsion engulfed the Pallavas due to the Kalabhra invasion of the Tamil country. Towards the close of the 6th century, the Pallava Simhavishnu stuck a blow against the Kalabhras. The Pandyas followed suit. Thereafter the Tamil country was divided between the Pallavas in the north with Kanchipuram as their capital, and Pandyas in the south with Madurai as their capital.[41]

Birudas

[edit]The royal custom of using a series of descriptive honorific titles, Birudas, was particularly prevalent among the Pallavas. The Birudas of Mahendravarman I are in Sanskrit, Tamil and Telugu. The Telugu Birudas show Mahendravarman's involvement with the Andhra region continued to be strong at the time he was creating his cave-temples in the Tamil region. The suffix "Malla" was used by the Pallava rulers.[42] Mahendravarman I used the Biruda, Shatrumalla, "a warrior who overthrows his enemies", and his grandson Paramesvara I was called Ekamalla "the sole warrior or wrestler". Pallava kings, presumably exalted ones, were known by the title Mahamalla ("great wrestler").[43]

Languages used

[edit]

Pallava inscriptions have been found in Tamil, Prakrit and Sanskrit.

Tamil was main language used by the Pallavas in their inscriptions, though a few records continued to be in Sanskrit.[44] At the time of the time of Paramesvaravarman I, the practice came into vogue of inscribing a part of the record in Sanskrit and the rest in Tamil. Almost all the copper plate records, viz., Kasakudi, Tandantottam, Pattattalmangalm, Udayendiram and Velurpalaiyam are composed both in Sanskrit and Tamil.[44]

Many Pallava royal inscriptions were in Sanskrit or Prakrit, considered the official languages. Similarly, inscriptions found in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka State are in Sanskrit and Prakrit.[45] Sanskrit was widely used by Simhavishnu and Narasimhavarman II in literature. The phenomenon of using Prakrit as official languages in which rulers left their inscriptions and epigraphies continued till the 6th century. It would have been in the interest of the ruling elite to protect their privileges by perpetuating their hegemony of Prakrit in order to exclude the common people from sharing power (Mahadevan 1995a: 173–188). The Pallavas in their Tamil country used Tamil and Sanskrit in their inscriptions.[46][44]

Writing system

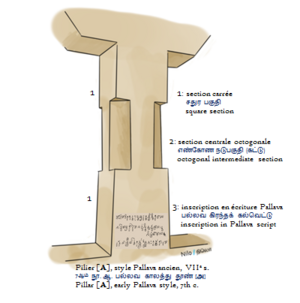

[edit]Under the Pallava dynasty, a unique form of Grantha script, a descendant of Pallava script which is a type of Brahmic script, was used. Around the 6th century, it was exported eastwards and influenced the genesis of almost all Southeast Asian scripts.

Religion

[edit]Pallavas were followers of Hinduism and made gifts of land to gods and Brahmins. In line with the prevalent customs, some of the rulers performed the Aswamedha and other Vedic sacrifices.[47] They were, however, tolerant of other faiths. The Chinese monk Xuanzang who visited Kanchipuram during the reign of Narasimhavarman I reported that there were 100 Buddhist monasteries, and 80 Hindu temples in Kanchipuram.[48] The semi-legendary founder of Zen Buddhism, Bodhidharma, is in an Indian tradition regarded to be the third son of a Pallava king.[49]

Pallava architecture

[edit]

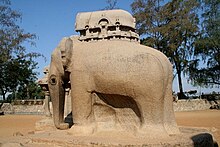

The Pallavas were instrumental in the transition from rock-cut architecture to stone temples. The earliest examples of Pallava constructions are rock-cut temples dating from 610 to 690 and structural temples between 690 and 900. A number of rock-cut cave temples bear the inscription of the Pallava king, Mahendravarman I and his successors.[50][51][52][53]

Among the accomplishments of the Pallava architecture are the rock-cut temples at Mamallapuram. There are excavated pillared halls and monolithic shrines known as Rathas in Mahabalipuram. Early temples were mostly dedicated to Shiva. The Kailasanatha temple in Kanchipuram and the Shore Temple built by Narasimhavarman II, rock cut temple in Mahendravadi by Mahendravarman are fine examples of the Pallava style temples.[54] The temple of Nalanda Gedige in Kandy, Sri Lanka is another. The famous Tondeswaram temple of Tenavarai and the ancient Koneswaram temple of Trincomalee were patronised and structurally developed by the Pallavas in the 7th century.[52][55]

Pallava society

[edit]The Pallava period beginning with Simhavishnu (575 CE – 900 CE) was a transitional stage in southern Indian society with monument building, foundation of devotional (bhakti) sects of Alvars and Nayanars, the flowering of rural Brahmanical institutions of Sanskrit learning, and the establishment of chakravartin model of kingship over a territory of diverse people; which ended the pre-Pallavan era of territorially segmented people, each with their culture, under a tribal chieftain.[56] While a system of ranked relationship among groups existed in the classical period, the Pallava period extolled ranked relationships based on ritual purity as enjoined by the shastras.[57] Burton distinguishes between the chakravatin model and the kshatriya model, and likens kshatriyas to locally based warriors with ritual status sufficiently high enough to share with Brahmins; and states that in south India the kshatriya model did not emerge.[57] As per Burton, south India was aware of the Indo-Aryan varna organised society in which decisive secular authority was vested in the kshatriyas; but apart from the Pallava, Chola and Vijayanagar line of warriors which claimed chakravartin status, only few locality warrior families achieved the prestigious kin-linked organisation of northern warrior groups.[57]

Chronology

[edit]Sastri chronology

[edit]The earliest documentation on the Pallavas is the three copper-plate grants, now referred to as the Mayidavolu (from Maidavolu village in Guntur district of Andhra Pradesh), Hirehadagali (from Hire Hadagali of Karnataka) and the British Museum plates (Durga Prasad, 1988) belonging to Skandavarman I and written in Prakrit.[58] Skandavarman appears to have been the first great ruler of the early Pallavas, though there are references to other early Pallavas who were probably predecessors of Skandavarman.[59] Skandavarman extended his dominions from the Krishna in the north to the Pennar in the south and to the Bellary district in the West. He performed the Aswamedha and other Vedic sacrifices and bore the title of "Supreme King of Kings devoted to dharma".[58]

The Hirahadagali copper plate (Bellary District) record in Prakrit is dated in the eighth year of Sivaskanda Varman to 283 CE and confirms the gift made by his father who is described merely as "Bappa-deva" (revered father) or Boppa. It will thus be clear that this dynasty of the Prakrit charters beginning with "Bappa-deva" were the historical founders of the Pallava dominion in southern India.[60][61]

The Hirahadagalli Plates were found in Hirehadagali, Bellary district and is one of the earliest copper plates in Karnataka and belongs to the reign of early Pallava ruler Shivaskanda Varma. Pallava King Sivaskandavarman of Kanchi of the early Pallavas ruled from 275 to 300 CE, and issued the charter in 283 CE in the eighth year of his reign.

As per the Hirahadagalli Plates of 283 CE, Pallava King Sivaskandavarman granted an immunity viz the garden of Chillarekakodumka, which was formerly given by Lord Bappa to the Brahmins, freeholders of Chillarekakodumka and inhabitants of Apitti. Chillarekakodumka has been identified by some as ancient village Chillarige in Bellary, Karnataka.[60]

In the reign of Simhavarman II, who ascended the throne in 436, the territories lost to the Vishnukundins in the north up to the mouth of the Krishna were recovered.[62] The early Pallava history from this period onwards is furnished by a dozen or so copper-plate grants in Sanskrit. They are all dated in the regnal years of the kings.[47]

The following chronology was composed from these charters by Nilakanta Sastri in his A History of South India:[47]

Early Pallavas

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| History of Tamil Nadu |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Andhra Pradesh and Telangana |

|---|

|

| History and Kingdoms |

- Simhavarman I (275–300)

- Shivskandvarman (unknown)

- Vijayskandavarman (unknown)

- Skandavarman (unknown)

- Vishnugopa I (350–355)

- Kumaravishnu I (350–370)

- Skandavarman II (370–385)

- Viravarman (385–400)

- Skandavarman III (400–436)

- Simhavarman II (436–460)

- Skandavarman IV (460–480)

- Nandivarman I (480–510)

- Kumaravishnu II (510–530)

- Buddhavarman (530–540)

- Kumaravishnu III (540–550)

- Simhavarman III (550–560)

Later Pallavas

[edit]

The incursion of the Kalabhras and the confusion in the Tamil country was broken by the Pandya Kadungon and the Pallava Simhavishnu.[63] Mahendravarman I extended the Pallava Kingdom and was one of the greatest sovereigns. Some of the most ornate monuments and temples in southern India, carved out of solid rock, were introduced under his rule. He also wrote the play Mattavilasa Prahasana.[64]

The Pallava kingdom began to gain both in territory and influence and were a regional power by the end of the 6th century, defeating kings of Ceylon and mainland Tamilakkam.[65] Narasimhavarman I and Paramesvaravarman I stand out for their achievements in both military and architectural spheres. Narasimhavarman II built the Shore Temple.

- Simhavishnu (575–600)[64]

- Mahendravarman I (600–630)[64]

- Narasimhavarman I (Mamalla) (630–668)[64]

- Mahendravarman II (668–672)

- Paramesvaravarman I (670–695)[64]

- Narasimhavarman II (Raja Simha) (695–722)[64]

- Paramesvaravarman II (705–710)

Later Pallavas of the Kadava Line

[edit]The kings that came after Paramesvaravarman II belonged to the collateral line of Pallavas and were descendants of Bhimavarman, the brother of Simhavishnu. They called themselves as Kadavas, Kadavesa and Kaduvetti. Hiranyavarman, the father of Nandivarman Pallavamalla is said to have belonged to the Kadavakula in epigraphs.[66] Nandivarman II himself is described as "one who was born to raise the prestige of the Kadava family".[67]

- Nandivarman II (Pallavamalla) (732–796) son of Hiranyavarman of Kadavakula[66][64]

- Dantivarman (795–846)[64]

- Nandivarman III (846–869)[64]

- Aparajitavarman (879–897)[64]

Aiyangar chronology

[edit]According to the available inscriptions of the Pallavas, historian S. Krishnaswami Aiyangar proposes the Pallavas could be divided into four separate families or dynasties; some of whose connections are known and some unknown.[68] Aiyangar states

We have a certain number of charters in Prakrit of which three are important ones. Then follows a dynasty which issued their charters in Sanskrit; following this came the family of the great Pallavas beginning with Simha Vishnu; this was followed by a dynasty of the usurper Nandi Varman, another great Pallava. We are overlooking for the present the dynasty of the Ganga-Pallavas postulated by the Epigraphists. The earliest of these Pallava charters is the one known as the Mayidavolu 1 (Guntur district) copper-plates.

Based on a combination of dynastic plates and grants from the period, Aiyangar proposed their rule thus:

Early Pallavas

[edit]- Bappadevan, chola prince (250–275) – married a Naga of Mavilanga (Kanchi)[citation needed] – The Great Founder of a Pallava lineage

- Shivaskandavarman I (275–300)

- Simhavarman (300–320)

- Bhuddavarman (320–335)

- Bhuddyankuran (335–340)

Middle Pallavas

[edit]- Visnugopa (340–355) (Yuvamaharaja Vishnugopa)

- Kumaravisnu I (355–370)

- Skanda Varman II (370–385)

- Vira Varman (385–400)

- Skanda Varman III (400–435)

- Simha Varman II (435–460)

- Skanda Varman IV (460–480)

- Nandi Varman I (480–500)

- Kumaravisnu II (c. 500–510)

- Buddha Varman (c. 510–520)

- Kumaravisnu III (c. 520–530)

- Simha Varman III (c. 530–537)

Later Pallavas

[edit]- Simhavishnu (537–570)

- Mahendravarman I (571–630)

- Narasimhavarman I (Mamalla) (630–668)

- Mahendravarman II (668–672)

- Paramesvaravarman I (672–700)

- Narasimhavarman II (Raja Simha) (700–727)

- Paramesvaravarman II (705–710)

Later Pallavas of the Kadava Line

[edit]- Nandivarman II (Pallavamalla) (732–796) son of Hiranyavarman of Kadavakula[66]

- Dantivarman (775–825)

- Nandivarman III (825–869)

- Nirupathungan (869–882)

- Aparajitavarman (882–896)

Genealogy of Māmallapuram Praśasti

[edit]The genealogy of Pallavas mentioned in the Māmallapuram Praśasti is as follows:[43]

- Vishnu

- Brahma

- Unknown / undecipherable

- Unknown / undecipherable

- Bharadvaja

- Drona

- Ashvatthaman

- Pallava

- Unknown / undecipherable

- Unknown / undecipherable

- Simhavarman I (c. 275)

- Unknown / undecipherable

- Unknown / undecipherable

- Simhavarman IV (436–c. 460)

- Unknown / undecipherable

- Unknown / undecipherable

- Skandashishya

- Unknown / undecipherable

- Unknown / undecipherable

- Simhavisnu (c. 550–585)

- Mahendravarman I (c. 571–630)

- Maha-malla Narasimhavarman I (630–668)

- Unknown / undecipherable

- Paramesvaravarman I (669–690)

- Rajasimha Narasimhavaram II (690–728)

- Unknown / undecipherable

- Pallavamalla Nandivarman II (731–796)

- Unknown / undecipherable

- Nandivarman III (846–869)

Relation with the Cholas

[edit]According to historian S. Krishnaswami Aiyengar, the Pallavas were natives of Tondaimandalam and the name Pallava is identical with the word Tondaiyar.[25] Chola Prince Ilandiraiyan is traditionally regarded as the founder of the Pallava dynasty.[26] Ilandiraiyan is referred to in the literature of the Sangam period such as the Pathupattu. In the Sangam epic Manimekalai, he is depected as the son of Chola king Killi and the Naga princess Pilivalai, the daughter of king Valaivanan of Manipallavam. When the boy grew up the princess wanted to send her son to the Chola kingdom. So she entrusted the prince to a merchant who dealt in woolen blankets called Kambala Chetty when his ship stopped in the island of Manipallavam. During the voyage to the Chola kingdom, the ship was wrecked due to rough weather and the boy was lost. He was later found washed ashore with a Tondai twig (creeper) around his leg. So he came to be called Tondaiman Ilam Tiraiyan meaning the young one of the seas or waves. When he grew up the northern part of the Chola kingdom was entrusted to him and the area he governed came to be called Tondaimandalam after him.He was a poet himself and four of his songs are extant even today.[69] He ruled from Tondaimandalam and was known as "Tondaman."[26]

Other relationships

[edit]Pallava royal lineages were influential in the old kingdom of Kedah of the Malay Peninsula under Rudravarman I, Champa under Bhadravarman I and the Kingdom of the Funan in Cambodia.[70] Some historians have claimed the present Pallar caste are descendants of the Pallavas who ruled the Andhra and Tamil countries between the 6th and 9th centuries.[citation needed] Tamil scholar M. Srinivasa Iyengar claimed claimed the Pallars were one of the communities who served often in Pallava armies.[71]

The similarity of the name ending "-varman" of Pallava rulers with that of Hindu kings during the Hindu/Buddhist era of Indonesia such as king Mulavarman of the Kutai Martadipura Kingdom, king Purnawarman of the Tarumanagara kingdom, king Adityawarman of the Malayapura kingdom, etc. has been commented upon by historians since discovery.[72] There have been possible high relations and connections of the Hindu kingdoms of Indonesia with the Pallava dynasty and other Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms of India back then.

List of feudatories

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 146, map XIV.2 (e). ISBN 0226742210.

- ^ Vaidya C.V., Medieval History of Hindu India Volume 1, pg.281

- ^ Ancient Jaffna: Being a Research Into the History of Jaffna from Very Early Times to the Portuguese Period, C. Rasanayagam, p.241, Asian Educational Services 1926

- ^ Sen, Aloka Parasher (28 February 2021), "Defining the Early Deccan: A Re-think*", Settlement and Local Histories of the Early Deccan, Routledge, pp. 39–60, doi:10.4324/9781003155607-2, ISBN 978-1-003-15560-7, S2CID 229492642, retrieved 14 May 2023

- ^ Francis, Emmanuel (28 October 2021). "Pallavas". The Encyclopedia of Ancient History: 1–4. doi:10.1002/9781119399919.eahaa00499. ISBN 978-1-119-39991-9. S2CID 240189630.

- ^ The journal of the Numismatic Society of India, Volume 51, p.109

- ^ Alī Jāvīd and Tabassum Javeed. (2008). World heritage monuments and related edifices in India, p.107 [1]

- ^ Gabriel Jouveau-Dubreuil, The Pallavas, Asian Educational Services, 1995 - Art, Indic - 86 pages, p. 83

- ^ Past and present: Manasara (English translation), 14 May 2020

- ^ South Indian History Congress. (17 February 1980), Proceedings of the First Annual Conference, vol. 1, The Congress and The Madurai Kamaraj University Co-op Printing Press

- ^ N. Ramesan, Copper Plate Inscriptions of the State Museum, Volume 3, Issues 28-29 of Arch. series, Government of Andhra Pradesh, 1960, p. 55

- ^ Gautam Sengupta, Suchira Roychoudhury, Sujit Som, Past and present: ethnoarchaeology in India, Pragati Publications in collaboration with Centre for Archaeological Studies and Training, Eastern India, 2006, p. 133

((citation)): CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ValaiTamil. "Pallava, பல்லவம் Tamil Agaraathi, tamil-english dictionary, english words, tamil words". ValaiTamil. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Pallavas". tamilnation.org. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "About Tamil Nadu | Tamil Nadu Government Portal". www.tn.gov.in. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Sathianathaier 1970, pp. 255–256.

- ^ Aiyangar & Nilakanta Sastri 1960, pp. 315–316[missing long citation]: "This view, which till recently was no more than an intelligent guess, seems to gain support from a Prakrit Brahmi inscription recently discovered in the Palnad taluk of the Guntur district. In spite of its mutilated condition, it clearly mentions Sihavamma Simhavarman I of the Palava dynasty and Bharadaya gotta... This is the earliest Pallava inscription so far known."

- ^ Rama Rao 1967, pp. 47–48: "The Manchikallu Prakrt inscription mentions a Simhavamma or Simhavarman of the Pallava family and the Bharadvaja gotra and registers gifts made by him after performing Santi and Svastyayana for his victory and increase of strength."

- ^ Aiyangar & Nilakanta Sastri 1960, pp. 315–316.

- ^ Subramanian, K. R. (1989) [1932], Buddhist Remains in Andhra and the History of Andhra Between 225 and 610 A.D., Asian Educational Services, p. 71, ISBN 978-81-206-0444-5

- ^ Gopalachari, K. (1957), "The Satavahana Empire", in K. A. Nilakanta Sastri (ed.), A Comprehensive History of India, II: The Mauryas and Satavahanas 325 SC.-AD 300, Calcutta: Indian History Congress/Orient Longman, pp. 296–297, note 1: "The Andhradesa of our period was limited in the north by Kalinga and in the east by the sea; in the south it did not extend far beyond the northern part of the Nellore district (the Pallava Karmarashtra), in the west it extended far into the interior."

- ^ Aiyangar & Nilakanta Sastri 1960, pp. 314–316: "There is much in favour of the thesis that the Pallavas rose into prominence in the service of the Satavahanas in the south-eastern division of their empire, and attained independence when that power declined."

- ^ Aiyangar & Nilakanta Sastri 1960, pp. 314–316.

- ^ Sathianathaier 1970, p. 256: "S. Krishnaswami Aiyangar regards the Pallavas as the feudatories of the Satavahanas—officers and governors of the south-eastern part of their empire, equates the term Pallava with the terms Tondaiyar and Tondaman (people and rulers of Tonda-mandalam), and says that, after the fall of the Satavahana Empire, those feudatories 'founded the new dynasty of the Pallavas, as distinct from the older chieftains, the Tondamans of the region.'"

- ^ a b T. V. Mahalingam. Kāñcīpuram in early South Indian history. Asia Pub. House, 1969. p. 22.

- ^ a b c Ramaswamy 2007, p. 80.

- ^ a b Sircar 1970, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Kulke & Rothermund 2004, p. 120.

- ^ Stein, Burton (2016). "Book Reviews : Kancipuram in Early South Indian History, by T. V. Mahalingam (Madras : Asia Publishing House, 1969), pp. vii-243". The Indian Economic & Social History Review. 7 (2): 317–321. doi:10.1177/001946467000700208. ISSN 0019-4646. S2CID 144817627.: "...the rather well argued and plausible stand that the Palavas were indigenous to the central Tamil plain, Tondaimandalam..."

- ^ Sircar, Dines Chandra (1935), The Early Pallavas, Calcutta: Jitendra Nath De, pp. 5–6: "There can hardly be any doubt that this Aruvanadu between the Northern and Southern Pennars is the Arouarnoi of Ptolemy's Geography. This Arouarnoi is practically the same as the Kanci-mandala, i.e. the district round Kanci."

- ^ Aiyangar, S. K. (1928), "Introduction", in R. Gopalan (ed.), History of the Pallavas of Kanchi, University of Madras, pp. xi–xii: "... River South Pennar where began the division known as Aruvānādu, which extended northwards along the coast almost as far as the Northern Pennar."

- ^ Sathianathaier 1970, pp. 256–257.

- ^ H.V. Nanjundayya; L.K. Anathakrishna (1988). The Mysore tribes and castes, Vol 4. Mysore, Mysore University. p. 30. OCLC 830766457.

The following extract from the Census Report of Madras for 1891, gives them a higher status than they usually claim :— "They (the Kurubas) are the modern representatives of the ancient Kurumbas or Pallavas, who were once so powerful, throughout South India, but very little trace of their greatness now remains.

- ^ Dhere, Ramchandra Chintaman (2011). Rise of a Folk God: Vitthal of Pandharpur, South Asia Research. Feldhaus, Anne (trans.). Oxford University Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-19977-764-8.

The history of South India shows clearly that all the southern royal dynasties who arose from pastoralist, cowherd groups gained Kshatriya status by claiming to be Moon lineage Kshatriyas, by taking Yadu as their ancestor, and by continually keeping alive their pride in being 'Yadavas'. Many dynasties in South India, from the Pallavas to the Yadavarayas, were originally members of pastoralist, cowherd groups and belonged to Kuruba lineages.

- ^ Rapson, Edward James (1897). Indian Coins-Numismatics. K.J. Trübner. p. 37.

- ^ Vaidya C.V., History of Medieval Hindu India, pg.281

- ^ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 25, 145. ISBN 0226742210.

- ^ Agrawal, Ashvini (1989). "Chapter II: THE POLITICAL CONDITION OF INDIA BEFORE THE RISE OF GUPTAS - EASTERN INDIA". Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 60, 61. ISBN 81-208-0592-5.

- ^ Rev. H Heras, SJ (1931) Pallava Genealogy: An attempt to unify the Pallava Pedigrees of the Inscriptions, Indian Historical Research Institute

- ^ KR Subramanian. (1989). Buddhist remains in Āndhra and the history of Āndhra between 224 & 610 A.D, p.106-109

- ^ Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999), Ancient Indian History And Civilization, New Age International, p. 445, ISBN 9788122411980

- ^ Marilyn Hirsh (1987) Mahendravarman I Pallava: Artist and Patron of Māmallapuram, Artibus Asiae, Vol. 48, Number 1/2 (1987), pp. 109-130

- ^ a b Rabe, Michael D (1997). "The Māmallapuram Praśasti: A Panegyric in Figures". Artibus Asiae. 57 (3/4): 189–241. doi:10.2307/3249929. JSTOR 3249929.

- ^ a b c Venkayya, V (April 1911). "Velurpalaiyam Plates of Nandivarman III". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 43: 521–524. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00041617. JSTOR 25189883. S2CID 163316246.

- ^ Rajan K. (Jan-Feb 2008). Situating the Beginning of Early Historic Times in Tamil Nadu: Some Issues and Reflections, Social Scientist, Vol. 36, Number 1/2, pp. 40-78

- ^ Heras, p 38

- ^ a b c Nilakanta Sastri, A History of South India, p.92

- ^ Kulke and Rothermund, pp121–122

- ^ Hemanth, Ungal Anban (3 January 2021). "History of Bodhidharma — Mysteries & Secrets (Indian Pallava Prince)". Lessons from History. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ Nilakanta Sastri, pp412–413

- ^ James G. Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M, The Rosen Publishing Group, p. 399, ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8

- ^ a b "Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram". UNESCO.org. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ^ "Advisory body evaluation" (PDF). UNESCO.org. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ^ Nilakanta Sastri, p139

- ^ Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram, Dist. Kanchipuram Archived 29 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Archaeological Survey of India (2014)

- ^ Burton Stein (1980), Peasant state and society in medieval South India, Oxford University Press, pp. 63–64

- ^ a b c Burton Stein (1980), Peasant state and society in medieval South India, Oxford University Press, p. 70

- ^ a b Nilakanta Sastri, A History of South India, p.91

- ^ Nilakanta Sastri, A History of South India, p.91–92

- ^ a b Aiyangar, S. Krishnaswami (2003), "Early History Of The Pallavas", Some Contributions Of South India To Indian Culture, Cosmo Publications (15 July 2003), ISBN 978-8170200062

- ^ Moraes, George M. (1995), The Kadamba Kula: A History of Ancient and Mediaeval Karnataka, Asian Educational Services, p. 6, ISBN 9788120605954

- ^ Arunkumar, R. (2014), "Political History of Ancient South India" (PDF), Caste system in ancient South India, Gulbarga University/Shodhganga, hdl:10603/28091

- ^ Kulke and Rothermund, p.120

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sen, Sailendra (2013), A Textbook of Medieval Indian History, Primus Books, pp. 41–42, ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4

- ^ Kulke and Rothermund, p111

- ^ a b c V. Ramamurthy, History of Kongu, Volume 1, International Society for the Investigation of Ancient Civilization, 1986, p. 172

- ^ Eugen Hultzsch, South Indian Inscriptions, Volume 12, Manager of Publications, 1986, p. viii

- ^ S.Krishnaswami Aiyangar. Some Contributions Of South India To Indian Culture. Early History of the Pallavas

- ^ Sastri 1961, p. 126.

- ^ Cœdès, George (1 January 1968), The Indianized States of South-East Asia, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 9780824803681

- ^ Venkatasubramanian 1986, p. 35.

- ^ VOGEL, J. Ph. (1918). "The Yupa Inscriptions of King Mulavarman, from Koetei (East Borneo)". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië. 74 (1/2): 167–232. ISSN 1383-5408. JSTOR 20769898.

References

[edit]- Aiyangar, S. K.; Nilakanta Sastri, K. A. (1960), "The Pallavas", in R. C. Majumdar; K. K. Dasgupta (eds.), A Comprehensive History of India, Volume III, Part 1: A.D. 300–985, New Delhi: Indian History Congress/People's Publishing House

- Avari, Burjor (2007), India: The Ancient Past, New York: Routledge

- Hermann, Kulke; Rothermund D (2001) [2000], A History of India, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-32920-5

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004), A History of India (Fourth ed.), Routledge, ISBN 9780415329194

- Minakshi, Cadambi (1938), Administration and Social Life Under the Pallavas, Madras: University of Madras

- Prasad, Durga (1988), History of the Andhras up to 1565 A.D., Guntur, India: P.G. Publishers

- Sathianathaier, R. (1970) [first published 1954], "Dynasties of South India", in Majumdar, R. C.; Pusalkar, A. D. (eds.), The Classical Age, History and Culture of Indian People (Third ed.), Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, pp. 255–275

- Sircar, D. C. (1970) [first published 1954], "Genealogy and Chronology of the Pallavas", in Majumdar, R. C.; Pusalkar, A. D. (eds.), The Classical Age, History and Culture of Indian People (Third ed.), Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, pp. 275–290

- Raghava Iyengar, R (1949), Perumbanarruppatai, a commentary, Chidambaram, India: Annamalai University Press

External links

[edit] Media related to Pallava Empire at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pallava Empire at Wikimedia Commons