| UH-60 Black Hawk | |

|---|---|

| |

| A U.S. Army UH-60M Blackhawk landing, 2019 | |

| Role | Utility helicopter |

| Manufacturer | Sikorsky Aircraft |

| First flight | 17 October 1974 |

| Introduction | 1979 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | United States Army Republic of Korea Armed Forces Japan Self-Defense Forces Colombian Armed Forces |

| Produced | 1974–present |

| Number built | 5,000 by January 2023[1] |

| Developed from | Sikorsky S-70 |

| Variants | Sikorsky SH-60 Seahawk Sikorsky HH-60 Pave Hawk Sikorsky MH-60 Jayhawk Mitsubishi H-60 |

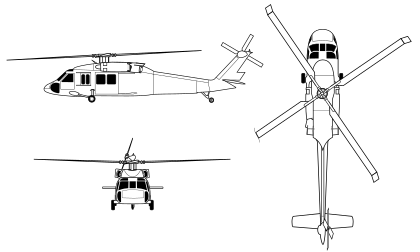

The Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk is a four-blade, twin-engine, medium-lift utility military helicopter manufactured by Sikorsky Aircraft. Sikorsky submitted the S-70 design for the United States Army's Utility Tactical Transport Aircraft System (UTTAS) competition in 1972. The Army designated the prototype as the YUH-60A and selected the Black Hawk as the winner of the program in 1976, after a fly-off competition with the Boeing Vertol YUH-61.

Named after the Native American war leader Black Hawk, the UH-60A entered service with the U.S. Army in 1979, to replace the Bell UH-1 Iroquois as the Army's tactical transport helicopter. This was followed by the fielding of electronic warfare and special operations variants of the Black Hawk. Improved UH-60L and UH-60M utility variants have also been developed. Modified versions have also been developed for the U.S. Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard. In addition to U.S. Army use, the UH-60 family has been exported to several nations. Black Hawks have served in combat during conflicts in Grenada, Panama, Iraq, Somalia, Ukraine, the Balkans, Afghanistan, and other areas in the Middle East.

Major variants include the Sikorsky SH-60 Seahawk used for naval purposes, Sikorsky HH-60 Pave Hawk for combat search and rescue, and many other types and upgrades including various export, VIP, special operation types. Various upgrades have taken place over the years and the latest version is the UH-60M.

Development

[edit]

Initial requirement

[edit]In the late 1960s, the United States Army began forming requirements for a helicopter to replace the UH-1 Iroquois, and designated the program as the Utility Tactical Transport Aircraft System (UTTAS). The Army also initiated the development of a new, common turbine engine for its helicopters that would become the General Electric T700. Based on experience in Vietnam, the Army required significant performance, survivability and reliability improvements from both UTTAS and the new powerplant.[2] The Army released its UTTAS request for proposals (RFP) in January 1972.[3] The RFP also included air transport requirements. Transport within the C-130 limited the UTTAS cabin height and length.[4]

The UTTAS requirements for improved reliability, survivability and lower life-cycle costs resulted in features such as dual-engines with improved hot and high altitude performance, and a modular design (reduced maintenance footprint); run-dry gearboxes; ballistically tolerant, redundant subsystems (hydraulic, electrical and flight controls); crashworthy crew (armored) and troop seats; dual-stage oleo main landing gear; ballistically tolerant, crashworthy main structure; quieter, more robust main and tail rotor systems; and a ballistically tolerant, crashworthy fuel system.[5]

Four prototypes were constructed, with the first YUH-60A flying on 17 October 1974. Prior to the delivery of the prototypes to the US Army, a preliminary evaluation was conducted in November 1975 to ensure the aircraft could be operated safely during all testing.[6] Three of the prototypes were delivered to the Army in March 1976, for evaluation against the rival Boeing-Vertol design, the YUH-61A, and one was kept by Sikorsky for internal research. The Army selected the UH-60 for production in December 1976. Deliveries of the UH-60A to the Army began in October 1978 and the helicopter entered service in June 1979.[7]

Upgrades and variations

[edit]

After entering service, the helicopter was modified for new missions and roles, including mine laying and medical evacuation. An EH-60 variant was developed to conduct electronic warfare and special operations aviation developed the MH-60 variant to support its missions.[8]

Due to weight increases from the addition of mission equipment and other changes, the Army ordered the improved UH-60L in 1987. The new model incorporated all of the modifications made to the UH-60A fleet as standard design features. The UH-60L also featured more power and lifting capability with upgraded T700-GE-701C engines and an improved gearbox, both from the SH-60B Seahawk.[9] Its external lift capacity increased by 1,000 lb (450 kg) up to 9,000 lb (4,100 kg). The UH-60L also incorporated the SH-60B's automatic flight control system (AFCS) for better flight control with more powerful engines.[10] Production of the L-model began in 1989.[9]

Development of the next improved variant, the UH-60M, was approved in 2001, to extend the service life of the UH-60 design into the 2020s. The UH-60M incorporates upgraded T700-GE-701D engines, improved rotor blades, and state-of-the-art electronic instrumentation, flight controls and aircraft navigation control. After the U.S. DoD approved low-rate initial production of the new variant,[11] manufacturing began in 2006,[12] with the first of 22 new UH-60Ms delivered in July 2006.[13] After an initial operational evaluation, the Army approved full-rate production and a five-year contract for 1,227 helicopters in December 2007.[14] By March 2009, 100 UH-60M helicopters had been delivered to the Army.[15] In November 2014, the US military ordered 102 aircraft of various H-60 types, worth $1.3 billion.[16]

Following their use in the operation to kill Osama bin Laden in May 2011, it emerged that the 160th SOAR used a secret version of the UH-60 modified with low-observable technology which enabled it to evade Pakistani radar. Analysis of the tail section, the only remaining part of the aircraft which crashed during the operation,[17][18] revealed extra blades on the tail rotor and other noise reduction measures, making the craft much quieter than conventional UH-60s. The aircraft appeared to include features like special high-tech materials, harsh angles, and flat surfaces found only in stealth jets.[Nb 1][19] Low observable versions of the Black Hawk have been studied as far back as the mid-1970s.[20]

In September 2012, Sikorsky was awarded a Combat Tempered Platform Demonstration (CTPD) contract to further improve the Black Hawk's durability and survivability. The company is to develop new technologies such as a zero-vibration system, adaptive flight control laws, advanced fire management, a more durable main rotor, full-spectrum crashworthiness, and damage-tolerant airframe; then they are to transition them to the helicopter. Improvements to the Black Hawk are to continue until the Future Vertical Lift program is ready to replace it.[21][22]

In December 2014, the 101st Airborne Division began testing new resupply equipment called the Enhanced Speed Bag System (ESBS). Soldiers in the field requiring quick resupply have depended on speed bags filled with items airdropped from a UH-60. However, all systems were ad hoc with bags not made to keep objects secure from impacts, so up to half of the airdropped items would be damaged upon hitting the ground. Started in 2011, the ESBS sought to standardize the airdrop resupply method and keep up to 90 percent of supplies intact. The system includes a hands-free reusable linear brake and expendable speed line and a multipurpose cargo bag. When the bag is deployed, the brake applies friction to the rope, slowing it down enough to keep the bag oriented down on the padded base, a honeycomb and foam kit inside to dissipate energy.[23][24][25]

The ESBS better protects helicopter-dropped supplies, and allows the Black Hawk to fly higher above the ground, 100 ft (30 m) up from 10 feet, while travelling 20 knots (23 mph; 37 km/h), limiting exposure to ground fire. Each bag can weigh 125–200 lb (57–91 kg) and up to six can be deployed at once, dropping at 40–50 feet per second (12–15 m/s). Since supplies can be delivered more accurately and the system can be automatically released on its own, the ESBS can enable autonomous resupply from unmanned helicopters.[23][24][25]

Design

[edit]

The UH-60 features four-blade main and tail rotors, and is powered by two General Electric T700 turboshaft engines.[26] The main rotor is fully articulated and has elastomeric bearings in the rotor head. The tail rotor is canted and features a rigid crossbeam.[27] The helicopter has a long, low profile shape to meet the Army's requirement for transporting aboard a C-130 Hercules, with some disassembly.[26] It can carry 11 troops with equipment, lift 2,600 pounds (1,200 kg) of cargo internally or 9,000 pounds (4,100 kg) of cargo (for UH-60L/M) externally by sling.[14]

The Black Hawk helicopter series can perform a wide array of missions, including the tactical transport of troops, electronic warfare, and aeromedical evacuation. A VIP version known as the VH-60N is used to transport important government officials (e.g., Congress, Executive departments) with the helicopter's call sign of "Marine One" when transporting the President of the United States.[citation needed] In air assault operations, it can move a squad of 11 combat troops or reposition a 105 mm M119 howitzer with 30 rounds ammunition and a four-man crew in a single lift.[14][28] The Black Hawk is equipped with advanced avionics and electronics for increased survivability and capability, such as the Global Positioning System.

The UH-60 can be equipped with stub wings at the top of the fuselage to carry fuel tanks or various armaments. The initial stub wing system is called External Stores Support System (ESSS).[29] It has two pylons on each wing to carry two 230 US gal (870 L) and two 450 US gal (1,700 L) tanks in total.[10] The four fuel tanks and associated lines and valves form the external extended range fuel system (ERFS).[citation needed] U.S. Army UH-60s have had their ESSS modified into the crashworthy external fuel system (CEFS) configuration, replacing the older tanks with up to four total 200 US gal (760 L) crashworthy tanks along with self-sealing fuel lines.[30] The ESSS can also carry 10,000 lb (4,500 kg) of armament such as rockets, missiles and gun pods.[10][31] The ESSS entered service in 1986. However, it was found that the four fuel tanks obstruct the field of fire for the door guns; thus, the external tank system (ETS), carrying two fuel tanks on the stub wings, was developed.[10]

The unit cost of the H-60 models varies due to differences in specifications, equipment and quantities. For example, the unit cost of the Army's UH-60L Black Hawk is $5.9 million while the Air Force HH-60G Pave Hawk has a unit cost of $10.2 million.[citation needed]

Operational history

[edit]The UH-60 Black Hawk is in service with 35 different countries as of 2024.[32]

Australia

[edit]

Australia bought early model UH-60 in the 1980s, and is buying a fleet of newer versions ones in the 2020s: Australia ordered fourteen S-70A-9 Black Hawks in 1986 and an additional twenty-five Black Hawks in 1987.[33][34] The first US-produced Black Hawk was delivered in 1987 to the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF).[33] de Havilland Australia produced thirty-eight Black Hawks under license from Sikorsky in Australia delivering the first in 1988 and the last in 1991.[35][33] In 1989, the RAAF's fleet of Black Hawks was transferred to the Australian Army.[33][36] The Black Hawks saw operational service in Cambodia, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, East Timor and Pakistan.[37]

In April 2009, the then-defence chief Air Chief Marshal Angus Houston, told the government not to deploy Black Hawks to Afghanistan as at the time they "lacked armor and self-defense systems", and despite an upgrade to address this underway, it was more practical to use allies' helicopters.[38][39] In 2004, the government selected the Multi-Role Helicopter (MRH-90) Taipan, a variant of the NHIndustries NH90, to replace the Black Hawk even though the Department of Defence had recommended the S‐70M Black Hawk.[40]

In January 2014, the Army began retiring the fleet of 34 Black Hawks from service (five had been lost in accidents) and had planned for this to be completed by June 2018.[41][42] The Chief of Army delayed the retirement of 20 Black Hawks until 2021 to enable the Army to develop a special operations role capable MRH-90.[43][44] On 10 December 2021, the S-70A-9 Black Hawks were retired from service.[45] On the same day, amid issues with the performance of the MRH-90s the government announced that they would be replaced by UH-60M Black Hawks.[45][46] In January 2023, the Army announced the acquisition of 40 UH-60Ms with deliveries commencing in 2023.[47]

Brazil

[edit]Brazil received four UH-60L helicopters in 1997, for the Brazilian Army peacekeeping forces. It received six UH-60Ls configured for special forces, and search and rescue uses in 2008. It ordered ten more UH-60Ls in 2009; deliveries began in March 2011.[48]

China

[edit]In December 1983, examples of the Aerospatiale AS-332 Super Puma, Bell 214ST SuperTransport and Sikorsky S-70A-5 (N3124B) were airlifted to Lhasa for testing. These demonstrations included take-offs and landings at altitudes to 17,000 feet (5,200 m) and en route operations to 24,000 feet (7,300 m). At the end of this testing, the People's Liberation Army purchased 24 S-70C-2s, equipped with more powerful GE T700-701A engines for improved high-altitude performance.[49] While designated as civil variants of the S-70 for export purposes, they are operated by the People's Liberation Army Aviation units.

Colombia

[edit]

Colombia first received UH-60s from the United States in 1987. The Colombian National Police, Colombian Aerospace Force, and Colombian Army use UH-60s to transport troops and supplies to places which are difficult to access by land for counter-insurgency (COIN) operations against drug and guerrilla organizations, for search and rescue, and for medical evacuation. Colombia also operates a militarized gunship version of the UH-60, with stub wings, locally known as Arpía (English: Harpy).[50][51]

The Colombian Army became the first worldwide operator of the S-70i with Terrain Awareness and Warning Capability (HTAWS) after taking delivery of the first two units on 13 August 2013.[52]

Israel

[edit]The Israeli Air Force (IAF) received 10 surplus UH-60A Black Hawks from the United States in August 1994.[53] Named Yanshuf (English: Owl) by the IAF,[54] the UH-60A began replacing Bell 212 utility helicopters.[53] The IAF first used the UH-60s in combat during 1996 in southern Lebanon[53] in Operation Grapes of Wrath against Hezbollah.

Mexico

[edit]

The Mexican Air Force ordered its first two UH-60Ls in 1991 to transport special forces units, and another four in 1994.[55] In July and August 2009, the Federal Police used UH-60s in attacks on drug traffickers.[56][57] In August 2011, the Mexican Navy received three upgraded and navalized UH-60M.[58] On 21 April 2014, the U.S. State Department approved the sale of 18 UH-60Ms to Mexico pending approval from Congress.[59] In September 2014, Sikorsky received a $203.6 million (~$258 million in 2023) firm-fixed-price contract modification for the 18 UH-60s designated for the Mexican Air Force.[60]

Philippines

[edit]

2 S-70-A5 VIP helicopters purchased 1983 and was delivered in 1984, this Blackhawk served the 250th PAW for more than 3 decades as a Presidential VVIP transport helicopter. Only 1 remains in service with the 505th Search and Rescue Group.[61]

In March 2019, the Philippines' Department of National Defense (DND) signed a contract worth US$241.4 million (~$284 million in 2023) with Lockheed Martin's Polish subsidiary PZL Mielec for 16 Sikorsky S-70i Black Hawks to the PAF.[62] On 10 December 2020, the PAF commissioned their first batch of six S-70i Blackhawks, with the remaining 10 to be delivered in 2021.[63] In June 2021, the air service received a second batch of five helicopters.[64] In November 2021, the third batch of five arrived.[65]

On 22 February 2022, DND and PZL Mielec formally signed the US$624 million contract for 32 additional S-70i Black Hawks,[66] totalling to around 48 units ordered.[67] This will make the Philippine Air Force the largest user of S-70i Blackhawk Helicopters globally.[68]

Poland

[edit]In January 2019, Poland ordered four S-70i Black Hawks with four delivered to the Polish Special Forces in December of that same year.[69] Another four S-70i helicopters are on order with two scheduled for delivery in 2023 and two in 2024.[69] In July 2023, Poland launched a procurement tender for S-70i Black Hawks with a goal to order approximately 32 helicopters.[70]

Slovakia

[edit]In February 2015, the U.S. State Department approved a possible Foreign Military Sale of nine UH-60Ms with associated equipment and support to Slovakia and sent it to Congress for its approval.[71][72] In April 2015, Slovakia's government approved the procurement of nine UH-60Ms along with training and support.[73][74] In September 2015, Slovakia ordered four UH-60Ms.[75] The first two UH-60Ms were delivered in June 2017; the Slovak Air Force had received all nine UH-60Ms by January 2020. These are to replace its old Soviet Mil Mi-17s.[76][77][78] In 2020, the Slovak minister of defense announced Slovakia's interest in buying two more UH-60Ms.[79]

Slovak Training Academy from Košice, a private company, operates four older UH-60As for new pilot training.[80]

Sweden

[edit]

Sweden requested 15 UH-60M helicopters by Foreign Military Sale in September 2010.[81] The UH-60Ms were ordered in May 2011, and deliveries began in January 2012.[82] In March 2013, Swedish ISAF forces began using Black Hawks in Afghanistan for MEDEVAC purposes.[83] The UH-60Ms have been fully operational since 2017.[84] Sweden designates it the Helicopter 16 (Hkp 16).[citation needed] In June 2024, Sweden ordered 12 more UH-60Ms from the US.[85]

Taiwan

[edit]Taiwan (Republic of China) operated S-70C-1/1A after the Republic of China Air Force received ten S-70C-1A and four S-70C-1 Bluehawk helicopters in June 1986 for Search and Rescue.[86] Four more S-70C-6s were received in April 1998. The ROC Navy received the first of ten S-70C(M)-1s in July 1990. 11 S-70C(M)-2s were received beginning April 2000.[87] In January 2010, the US announced approval for a Foreign Military Sale of 60 UH-60Ms to Taiwan[88] with 30 designated for the Army, 15 for the National Airborne Service Corps (including the one that crashed off Orchid Island in 2018) and 15 for the Air Force Rescue Group (including the one that crashed 2 January 2020).[89]

Turkey

[edit]Turkey has operated the UH-60 during NATO deployments to Afghanistan and the Balkans. The UH-60 has also been used in counter-terror/internal security operations.[citation needed]

The Black Hawk competed against the AgustaWestland AW149 in the Turkish General Use Helicopter Tender, to order up to 115 helicopters and produce many of them indigenously, with Turkish Aerospace Industries responsible for final integration and assembly.[90][91] On 21 April 2011, Turkey announced the selection of Sikorsky's T-70.[92][93][94]

In the course of the coup d'état attempt in Turkey on 15 July 2016, eight Turkish military personnel of various ranks landed in Greece's northeastern city of Alexandroupolis on board a Black Hawk helicopter and claimed political asylum in Greece.[95] The helicopter was returned to Turkey shortly thereafter.[96]

Ukraine

[edit]In February 2023, Ukraine's Main Directorate of Intelligence (HUR) published a video showing them operating at least two UH-60s painted in Ukrainian colors.[97] The helicopters appeared to have minimal modifications, namely the addition of two M240 7.62 mm machine guns for defensive purposes.[97] It was confirmed that at least one of these was purchased by a third party, Ace Aeronautics, following a Czech crowdfunding effort that raised US$6 million.[98] On 17 March 2024, Russia claimed to have shot down a UH-60 during the 2024 western Russia incursion, claiming it was a "troop transport" carrying 20 troops into combat. However, it was revealed to be a Mil Mi-8 instead.[99]

United States

[edit]

The UH-60 entered service with the U.S. Army's 101st Combat Aviation Brigade of the 101st Airborne Division in June 1979.[100] The U.S. military first used the UH-60 in combat during the invasion of Grenada in 1983, and again in the invasion of Panama in 1989. During the Gulf War in 1991, the UH-60 participated in the largest air assault mission in U.S. Army history with over 300 helicopters involved. Two UH-60s (89-26214 and 78–23015) were shot down, both on 27 February 1991, while performing Combat Search and Rescue of other downed aircrews, an F-16C pilot and the crew of a MEDEVAC UH-1H that were shot down earlier that day.[101]

In 1993, Black Hawks featured prominently in the Battle of Mogadishu in Somalia. Black Hawks also saw action in the Balkans and Haiti in the 1990s.[10] U.S. Army UH-60s and other helicopters conducted many air assaults and other support missions during the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The UH-60 has continued to serve in operations in Afghanistan and Iraq.[10]

Customs and Border Protection Office of Air and Marine (OAM) uses the UH-60 in its operations specifically along the southwest border. The Black Hawk has been used by OAM to interdict illegal entry into the U.S. Additionally, OAM regularly uses the UH-60 in search and rescue operations. Highly modified H-60s were employed during the U.S. Special Operations mission that resulted in the death of Osama bin Laden during Operation Neptune Spear on 1 May 2011.[19][102] One such MH-60 helicopter crash-landed during the operation and was destroyed by the team before it departed in the other MH-60 and a backup MH-47 Chinook with bin Laden's remains. Two MH-47s were used for the mission to refuel the two MH-60s and as backups.[103] News media reported that the Pakistani government granted the Chinese military access to the wreckage of the crashed 'stealth' UH-60 variant in Abbottabad;[104][105][106] Pakistan and China denied the reports,[104][105] and the U.S. government has not confirmed Chinese access.[105]

In U.S. service, the Army plans to eventually replace it with a tilt-rotor aircraft, the V-280 Valor; In December 2022, the V-280 was chosen by the US Army as the winner of the Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft program to replace UH-60 Blackhawk in Army service.[107][108] (that does not mean all UH-60 variants will be replaced, its for the Army version)

Additional users

[edit]The United Arab Emirates requested 14 UH-60M helicopters and associated equipment in September 2008, through Foreign Military Sale.[109] It had received 20 UH-60Ls by November 2010.[110] Bahrain ordered nine UH-60Ms in 2007.[111][112]

In December 2011, the Royal Brunei Air Force (RBAirF / TUDB) ordered twelve S-70i helicopters, which are similar to the UH-60M; four aircraft had been received by December 2013.[113] In June 2012, the U.S. Defense Security Cooperation Agency notified Congress that Qatar requested the purchase of twelve UH-60Ms, engines, and associated equipment.[114] The Royal Brunei Air Force had earlier bought four UH-60, but these were later sold to Malaysia.[115]

In May 2014, Croatian Defence Minister Ante Kotromanović announced the beginning of negotiations for the purchase of 15 used Black Hawks.[116] In October 2018, the US via Ambassador Robert Kohorst announced donation of two UH-60M helicopters with associated equipment and crew training to Croatia's Ministry of Defence, to be delivered in 2020.[117] In October 2019, the US State Dept approved the sale of two new UH-60M Blackhawks.[118][119] In February 2022, the first two helicopters were delivered to Croatia.[120][121] In January 2024, the State Department approved a possible Foreign Military Sale to Croatia for 8 UH-60M helicopters and related equipment and services for an estimated cost of $500 million.[122] The U.S. government has provided $139.4 million in financial assistance for 51 percent of the funding, as a compensation for the Croatian donation of 14 Mi-8 helicopters to Ukraine. The remaining sum is be provided by Croatia's Ministry of Defence in the three-year budget period from 2025 to 2027. The Letter of Offer and Acceptance was signed in March 2024.[123] Delivery of all 8 Black Hawks is expected in 2028.[124]

Tunisia requested 12 armed UH-60M helicopters in July 2014 through Foreign Military Sale.[125] In August 2014, the U.S. ambassador stated that the U.S. "will soon make available" the UH-60Ms to Tunisia.[126] The sale of 8 helicopters was approved and helicopters were delivered 2017 and 2018.[127]

In January 2015, the Malaysian Defence Minister Hishammuddin Hussein confirmed that Royal Malaysian Air Force (RMAF) is receiving S-70A Blackhawks from the Brunei government. These helicopters, believed to be four in total, were expected to be transferred to Malaysia by September with M134D miniguns added. The four Blackhawks were delivered to Royal Brunei Air Force (RBAirF / TUDB) in 1999.[115]

In 2018, Latvia requested to buy four UH-60M Black Hawks with associated equipment for an estimated cost of $200 million (~$239 million in 2023). In August 2018, the State Department approved the possible Foreign Military Sale. The Defense Security Cooperation Agency delivered the required certification notifying Congress of the possible sale.[128] In November 2018, Latvia ordered four UH-60Ms, and received the first two in December 2022.[129]

In 2019, Lithuania announced plans to buy six UH-60M helicopters[130] before ordering four UH-60Ms in 2020.[131] In July 2020, the US State Department approved the possible Foreign Military Sale of six UH-60Ms and associated equipment to Lithuania for $380 million.[132] In November 2020, Lithuania signed a contract worth $213 million for four UH-60Ms with an option to purchase two more aircraft.[133][134] Preparations are almost complete including facilities and training, with deliveries expected in late 2024.[135][136]

In 2019, Poland ordered four S-70i helicopters for its special forces.[137] As of 2023 there is negotiations to purchase additional S-70i helicopters.[138]

In August 2023, the Portuguese Air Force shared a photo on twitter of the first flight of one of the six UH-60s purchased from Arista Aviation Services.[139] The Portuguese armed forces conducted its first operation flight of its UH-60 in December 2023.[140]

In December 2023, the Hellenic Army selected the UH-60Ms for a possible order of 35 aircraft and associated equipment for an estimated cost of $1.95 billion pending the deal clears Congress.[141][142] This order was approved by US and Greek governments, and a contract for 35 helicopters agreed by April 2024.[143][144] In Greek service it will replace aged Bell UH-1H and Agusta-Bell AB205.[144] Greece already operates S-70B and MH-60R helicopters.[145]

Future and potential users

[edit]In February 2013, the Indonesian Army announced its interest in buying UH-60 Black Hawks to modernize its weaponry. The army wants them for combating terrorism, transnational crime, and insurgency to secure the archipelago.[146] In August 2023, Indonesian Aerospace and Lockheed Martin signed an agreement for the procurement of 24 UH-60/S-70 Blackhawks.[147][148]

In 2022, the Royal Air Force and British Army expects to select a helicopter for the New Medium Helicopter program to replace several existing helicopters. Sikorsky has indicated it expects its S-70M to meet the requirement to participate in this procurement selection program.[149]

Variants

[edit]

The UH-60 comes in many variants and many different modifications. The U.S. Army variants can be fitted with stub wings to carry additional fuel tanks or weapons.[10] Variants may have different capabilities and equipment to fulfil different roles.

Utility variants

[edit]- YUH-60A: Initial test and evaluation version for U.S. Army. First flight on 17 October 1974. Three were built.

- UH-60A Black Hawk: Original U.S. Army version, carrying a crew of four and up to 11 equipped troops.[150][verification needed] Equipped with T700-GE-700 engines.[151] Produced 1977–1989. U.S. Army is equipping UH-60As with more powerful T700-GE-701D engines and also upgrading A-models to UH-60L standards.[152]

- UH-60C Black Hawk: Modified version for command and control (C2) missions.[10][151]

- CH-60E: Proposed troop transport variant for the U.S. Marine Corps.[153]

- UH-60L Black Hawk: UH-60A with upgraded T700-GE-701C engines, improved durability gearbox, and updated flight control system.[10] Produced 1989–2007.[154] UH-60Ls are also being equipped with the GE T700-GE-701D engine.[152] The U.S. Army Corpus Christi Army Depot is upgrading UH-60A helicopters to the UH-60L configuration. In July 2018, Sierra Nevada Corporation proposed upgrading some converted UH-60L helicopters for the U.S. Air Force's UH-1N replacement program.[155]

- UH-60M Black Hawk: Improved design wide chord rotor blades, T700-GE-701D engines (max 2,000 shp or 1,500 kW each), improved durability gearbox, Integrated Vehicle Health Management System (IVHMS) computer, and new glass cockpit. Production began in 2006.[156] Planned to replace older U.S. Army UH-60s.[157]

- UH-60M Upgrade Black Hawk: UH-60M with fly-by-wire system and Common Avionics Architecture System (CAAS) cockpit suite. Flight testing began in August 2008.[158]

- UH-60V Black Hawk: Upgraded version of the UH-60L with the electronic displays (glass cockpit) of the UH-60M. Upgrades performed by Northrop Grumman featuring a centralized processor with a partitioned, modular operational flight program enabling capabilities to be added as software-only modifications.[159]

Special purpose

[edit]- EH-60A Black Hawk: UH-60A with modified electrical system and stations for two electronic systems mission operators. All examples of type have been converted back to standard UH-60A configuration.[151]

- YEH-60B Black Hawk: UH-60A modified for special radar and avionics installations, prototype for stand-off target acquisition system.[151]

- EH-60C Black Hawk: UH-60A modified with special electronics equipment and external antenna.[151] (All examples of type have been taken back to standard UH-60A configuration.)

- EUH-60L (no official name assigned): UH-60L modified with additional mission electronic equipment for Army Airborne C2.[151]

- EH-60L Black Hawk: EH-60A with major mission equipment upgrade.[151]

- UH-60Q Black Hawk: UH-60A modified for medical evacuation.[151][160] The UH-60Q is named DUSTOFF for "dedicated unhesitating service to our fighting forces".[161]

- HH-60L (no official name assigned): UH-60L extensively modified with medical mission equipment.[151] Components include an external rescue hoist, integrated patient configuration system, environmental control system, onboard oxygen system (OBOGS), and crash-worthy ambulatory seats.[160]

- HH-60M Black Hawk: UH-60M with medical mission equipment (medevac version) for U.S. Army.[151][162]

- HH-60U: USAF UH-60M version modified with an electro-optical sensor and rescue hoist. Three in use by Air Force pilots and special mission aviators since 2011. Has 85% commonality with the HH-60W.[163]

- HH-60W Jolly Green II: Modified version of the UH-60M for the U.S. Air Force as a Combat Rescue Helicopter to replace HH-60G Pave Hawks with greater fuel capacity and more internal cabin space, dubbed the "60-Whiskey". Deliveries to the USAF of the HH-50W began in 2020.The 41st Rescue Squadron received the first two HH-60W helicopters on 5 November 2020.[164][165]

- MH-60A Black Hawk: 30 UH-60As modified with additional avionics, night vision capable cockpit, FLIR, M134 door guns, internal auxiliary fuel tanks and other Special Operations mission equipment in early 1980s for U.S. Army.[166][167] Equipped with T700-GE-701 engines.[151] Variant was used by the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment. The MH-60As were replaced by MH-60Ls beginning in the early 1990s and passed to Army Aviation units in the Army National Guard.[153][168]

- MH-60L Black Hawk: Special operations modification, used by the U.S. Army's 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment ("Night Stalkers"), based on the UH-60L with T700-701C engines. It was developed as an interim version in the late 1980s pending the fielding of the MH-60K specifically designed for the 160th SOAR(A).[169] Equipped with many of the systems used on MH-60K, including FLIR, color weather map, auxiliary fuel system, and laser rangefinder/designator.[169][170] A total of 37 MH-60Ls were built and some 10 had received an in-flight refueling probe by 2003.[169]

- MH-60L DAP: The Direct Action Penetrator (DAP) is a special operations modification of the baseline MH-60L, operated by the U.S. Army's 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment.[171] The DAP is configured as a gunship, with no troop-carrying capacity. The DAP is equipped with ESSS or ETS stub wings, each capable of carrying configurations of the M230 Chain Gun 30 mm automatic cannon, 19-shot Hydra 70 rocket pod, AGM-114 Hellfire missiles, AIM-92 Stinger air-to-air missiles, GAU-19 gun pods, and M134 minigun pods,[172] M134D miniguns are used as door guns.[167]

- MH-60K Black Hawk: Special operations modification first ordered in 1988 for use by the U.S. Army's 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment ("Night Stalkers").[153] Equipped with the in-flight refueling probe,[173] and T700-GE-701C engines. More advanced than the MH-60L, the K-model also includes an integrated avionics system (glass cockpit), AN/APQ-174B terrain-following radar, color weather map, improved weapons capability, and various defensive systems.[173][174]

- MH-60M Black Hawk: Special operations version of UH-60M for U.S. Army. Equipped with in-flight refueling probe, Rockwell Collins Common Avionics Architecture System (CAAS) glass cockpit, updated sensors and defensive systems such as the AN/APQ-187 Silent Knight terrain-following radar, and more powerful YT706-GE-700 engines.[175][176] All special operations Black Hawks to be modernized to MH-60M standard by 2015. The MH-60M can be configured either as an assault helicopter carrying troops or as a DAP gunship.[177]

- MH-60 Black Hawk stealth helicopter: One of two (known) specially modified MH-60s used in the raid on Osama bin Laden's compound in Pakistan on 1 May 2011 was damaged in a hard landing, and was subsequently destroyed by U.S. forces.[178][179] Subsequent reports state that the Black Hawk destroyed was a previously unconfirmed but rumored, modification of the design with reduced noise signature and stealth technology.[18][19] The modifications are said to add several hundred pounds to the base helicopter including edge alignment panels, special coatings and anti-radar treatments for the windshields.[19]

- UH-60A RASCAL: NASA-modified version for the Rotorcraft-Aircrew Systems Concepts Airborne Laboratory; a US$25M program for the study of helicopter manoeuvrability in three programs, Superaugmented Controls for Agile Maneuvering Performance (SCAMP), Automated Nap-of-the-Earth (ANOE) and Rotorcraft Agility and Pilotage Improvement Demonstration (RAPID).[180][181] The UH-60A RASCAL performed a fully autonomous flight on 5 November 2012. U.S. Army personnel were on board, but the flying was done by helicopter. During a two-hour flight, the Black Hawk featured terrain sensing, trajectory generation, threat avoidance, and autonomous flight control. It was fitted with a 3D-LZ laser detection and ranging (LADAR) system. The autonomous flight was performed between 200 and 400 feet. Upon landing, the onboard technology was able to pinpoint a safe landing zone, hover, and safely bring itself down.[182]

- OPBH: On 11 March 2014, Sikorsky successfully conducted the first flight demonstration of their Optionally Piloted Black Hawk (OPBH), a milestone part of the company's Manned/Unmanned Resupply Aerial Lifter (MURAL) program to provide autonomous cargo delivery for the U.S. Army. The helicopter used the company's Matrix technology (software to improve features of autonomous, optionally-piloted VTOL aircraft) to perform autonomous hover and flight operations under the control of an operator using a man-portable Ground Control Station (GCS). The MURAL program is a cooperative effort between Sikorsky, the US Army Aviation Development Directorate (ADD), and the US Army Utility Helicopters Project Office (UH PO). The purpose of creating an optionally-manned Black Hawk is to make the aircraft autonomously carry out resupply missions and expeditionary operations while increasing sorties and maintaining crew rest requirements and leaving pilots to focus more on sensitive operations.[183][184]

- VH-60D Night Hawk: VIP-configured HH-60D, used for presidential transport by USMC. T700-GE-401C engines.[151] Variant was later redesignated VH-60N.[185]

- VH-60N White Hawk "White Top": Modified UH-60A with some features from the SH-60B/F Seahawks.[186] Is one of the VIP-configured USMC helicopter models that perform Presidential and VIP transport as Marine One. The VH-60N entered service in 1988 and nine helicopters were delivered.[186]

- VH-60M Black Hawk "Gold Top": Heavily modified UH-60M used for executive transport. Members of the Joint Chiefs, Congressional leadership, and other DoD personnel are flown on these exclusively by Alpha company 12th Aviation Battalion at Fort Belvoir, Virginia.[citation needed]

Export versions

[edit]- UH-60J Black Hawk: Variant for the Japanese Air Self Defense Force and Maritime Self Defense Force produced under license by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. Also known as the S-70-12.[187]

- UH-60JA Black Hawk: Variant for the Japanese Ground Self Defense Force. It is a license produced by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries.[187]

- AH-60L Arpía: Export version for Colombia developed by Elbit Systems, Sikorsky, and the Colombian Aerospace Force. It is Counter-insurgency (COIN) attack version with improved electronics, firing system, FLIR, radar, light rockets and machine guns.[10][188]

- AH-60L Battle Hawk: Export armed version unsuccessfully tendered for Australian Army[10] project AIR87, similar to AH-60L Arpía III. Sikorsky has also offered a Battlehawk armed version for export in the form of armament kits and upgrades. Sikorsky's Armed Black Hawk demonstrator has tested a 20 mm turreted cannon, and different guided missiles.[189][190] The United Arab Emirates ordered Battlehawk kits in 2011.[191]

- UH-60P Black Hawk: Version for South Korean Army, based on UH-60L with some improvements.[153] Around 150 were produced under license by Korean Air.[151][192]

- S-70A Black Hawk: Sikorsky's designation for Black Hawk. The designation is often used for exports.

- S-70A-1 Desert Hawk: Export version for the Royal Saudi Land Forces.

- S-70A-L1 Desert Hawk: Aeromedical evacuation version for the Royal Saudi Land Forces.

- S-70A-5 Black Hawk: Export version for the Philippine Air Force.

- S-70A-6 Black Hawk: Export version for Thailand.

- S-70A-9 Black Hawk: Export version for Australia, assembled under licence by Hawker de Havilland. The first eight were delivered to the Royal Australian Air Force, subsequently transferred to the Australian Army; the remainder were delivered straight to the Army after rotary-wing assets were divested by the Air Force in 1989.[193]

- S-70A-11 Black Hawk: Export version for the Royal Jordanian Air Force.

- S-70A-12 Black Hawk: Search and rescue model for the Japanese Air Self Defense Force and Maritime Self Defense Force. Also known as the UH-60J.

- S-70A-14 Black Hawk: Export version for Brunei.

- S-70A-16 Black Hawk: Engine test bed for the Rolls-Royce/Turbomeca RTM 332.

- S-70A-17 Black Hawk: Export version for Turkey.

- S-70A-18 Black Hawk: UH-60P and HH-60P for Republic of Korea Armed Forces built under license.[194]

- Sikorsky/Westland S-70-19 Black Hawk: This version is built under license in the United Kingdom by Westland. Also known as the WS-70.[citation needed]

- S-70A-20 Black Hawk: VIP transport version for Thailand.

- S-70A-21 Black Hawk: Export version for Egypt.

- S-70A-22 Black Hawk: VH-60P for South Korea built under license. Used for VIP transport by the Republic of Korea Air Force. Its fuselage is tipped with white to distinguish it from normal HH-60P.[195]

- S-70A-24 Black Hawk: Export version for Mexico.

- S-70A-26 Black Hawk: Export version for Morocco.

- S-70A-27 Black Hawk: Export version for Royal Hong Kong Auxiliary Air Force and Hong Kong Government Flying Service; three built.[196][197]

- S-70A-28D Black Hawk: Export version for Turkish Army.[198]

- S-70A-30 Black Hawk: Export version for Argentine Air Force, used as a VIP transport helicopter by the Presidential fleet; one built.[199]

- S-70A-33 Black Hawk: Export version for Royal Brunei Air Force.

- S-70A-39 Black Hawk: VIP transport version for Chile; one built.

- S-70A-42 Black Hawk: Export version for Austria.

- S-70A-43 Black Hawk: Export version for Royal Thai Army.

- S-70A-50 Black Hawk: Export version for Israel; 15 built.

- S-70C-2 Black Hawk: Export version for the People's Republic of China; 24 built.[49]

- S-70i Black Hawk: International military version assembled by Sikorsky's subsidiary, PZL Mielec in Poland.[200]

- S-70M Black Hawk: Modified military version assembled by Sikorsky's subsidiary, PZL Mielec in Poland from 2021.[201]

- See: Sikorsky SH-60 Seahawk, Sikorsky HH-60 Pave Hawk, Piasecki X-49, and Sikorsky HH-60 Jayhawk for other Sikorsky S-70 variants.

Operators

[edit]

See SH-60 Seahawk, HH-60 Pave Hawk, and HH-60 Jayhawk for operators of military H-60/S-70 variants; see Sikorsky S-70 for non-military operators of other H-60/S-70 family helicopters.

Afghanistan

Afghanistan

- Taliban (captured from the Afghan Air Force in August 2021)[202]

Albania

Albania

- Albanian Air Force 2 (4 on order)[203][204]

Australia

Australia

- Australian Army - 14 and 25 in original orders in 1986 and 1987. Retired in 2021 with 5 lost. 40 ordered in 2023 for delivery in 2024.[205]

- Royal Australian Navy (see H-60 Seahawk)

Austria

Austria

Bahrain

Bahrain

Brazil

Brazil

Brunei

Brunei

Chile

Chile

People's Republic of China

People's Republic of China

Colombia

Colombia

- Colombian Aerospace Force[206] AH-60L Arpía[10] (24)

- Colombian Army[206] S-70i (7 as of 2013)[52]

Croatia

Croatia

- Croatian Air Force - 8 UH-60Ms being procured with 4 received as of March 2024.[207] 8 more on order.[208]

Egypt

Egypt

Greece

Greece

- Hellenic Army - 35 UH-60M ordered on 5 April 2024.[209]

Indonesia

Indonesia

- Indonesian Army - 22 S-70M Black Hawks on order.[210]

Israel

Israel

Japan

Japan

- Japan Air Self-Defence Force[206] UH-60J[187]

- Japan Ground Self-Defence Force[206] UH-60JA[187]

- Japan Maritime Self-Defence Force[206] UH-60J[187] (see also SH-60J/K/L)

Jordan

Jordan

Latvia

Latvia

- Latvian Air Force - UH-60M (2 received, another 2 on order)[211]

Lithuania

Lithuania

- Lithuanian Air Force - UH-60M (4 on order; deliveries to begin in late 2024.)[212]

Malaysia

Malaysia

- Malaysian Army - UH-60A+ (4 on lease, deliveries to begin in 2023)[213]

- Royal Malaysian Air Force[206]

Mexico

Mexico

Morocco

Morocco

Philippines

Philippines

- Philippine Air Force S-70i (21)[65] (27 on order)[66][215]

Poland

Poland

- Polish Special Forces - 4 S-70i helicopters[216][217] (4 on order)[69]

Portugal

Portugal

- Portuguese Air Force - UH-60A (9 ordered for aerial firefighting)[218][219] Two received as of 2023.[220]

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia

- Royal Saudi Air Force[206]

- Royal Saudi Land Forces[206]

- Saudi Arabian National Guard[206]

- Royal Saudi Navy[206]

Republic of Korea

Republic of Korea

- Republic of Korea Air Force[206]

- Republic of Korea Army[206] UH-60P[151]

- Republic of Korea Navy[206]

Slovakia

Slovakia

Sweden

Sweden

Taiwan (Republic of China)

Taiwan (Republic of China)

Thailand

Thailand

- Royal Thai Army[206] UH-60L;[221] UH-60M[221]

- Royal Thai Air Force

- Royal Thai Navy[206] (see SH-60)

Tunisia

Tunisia

Turkey

Turkey

- Turkish Air Force - (6 T-70s on order)[222] First unit delivered in January 2023.[223]

- Turkish Land Forces[206]- 22+ T-70 ordered. First delivered[224]

- Special Forces Command(Turkey) - 6 T-70s ordered with deliveries underway.[224]

- Turkish Naval Forces[225] (see Sikorsky SH-60 Seahawk)[224]

- Gendarmerie General Command (Turkey)[226] - 14 T-70s ordered with 3 delivered.[224][227]

- General Directorate of Security(Turkey)[228] - 20 T-70s ordered[224]

- General Directorate of Forestry(Turkey) - 3 T-70s ordered with 2 delivered.[224][229]

United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates

Ukraine

Ukraine

- Main Directorate of Intelligence (Ukraine) - 2 UH-60As[230] One more being crowdfunded for GUR by Czech supporters under the "Gift for Putin" (Dárek pro-Putina) initiative.[231]

United States

United States

- United States Air Force (see HH-60)

- United States Army[206]

- United States Navy (see SH-60)

- United States Coast Guard (see MH-60)

- United States Department of State

- United States Department of Homeland Security

Former operators

[edit] Islamic Republic of Afghanistan

Islamic Republic of Afghanistan

- Afghan Air Force (until Aug. 2021)[206]

Accidents

[edit]- From 1981 to 1987, five Black Hawks crashed (killing or injuring all on board) while flying near radio broadcast towers because their electromagnetic emissions disrupted the helicopters' flight control systems. The Black Hawk helicopters were not hardened against high-intensity radiated fields, contrary to the SH-60 Seahawk Navy version. The pilots were instructed to fly away from emitters, and, in the long term, shielding was increased and backup systems were installed.[234]

- On 29 July 1992, one Australian Army Black Hawk collided into terrain near Oakey Army Aviation Centre. Killing two occupants.[235]

- On 3 March 1994, a UH-60 helicopter of the 15th Fighter Wing, Republic of Korea Air Force (ROKAF) exploded above Yongin, Gyeonggi-do, killing all of the six personnel on board, including General Cho Kun-hae, then Chief of the Air Staff of South Korea.[236]

- On 14 April 1994, two U.S. Army UH-60 Black Hawks in northern Iraq were shot down by mistake by U.S. Air Force F-15s patrolling the northern no-fly zone that had been imposed after the 1991 Gulf War. Twenty-six crew and passengers were killed.[237]

- On 12 June 1996, two Australian Army Black Hawks collided during an Army night-time special forces counter-terrorism exercise resulting in the death of eighteen soldiers - fifteen members of the SASR and three from the 5th Aviation Regiment.[238][239][240]

- On 12 February 2001, two Black Hawks from Schofield Barracks, Hawaii collided during NVG formation flight training, causing loss of both aircraft, six deaths and 11 injured soldiers.[241]

- On 12 February 2004, one Australian Army Black Hawk collided into terrain in the vicinity of Mount Walker, Queensland following contact between the tail rotor and a tree. The airframe was written off however there were no deaths - six out of the eight occupants received injuries.[242][243]

- On 26 September 2004, a U.S. Army Black Hawk crashed taking off from Tallill Airbase (Nasiriyah Airport), Iraq. The crew of four was rescued.[244]

- On 29 November 2006, one Australian Army Black Hawk crashed into and subsequently slid off the deck of HMAS Kanimbla sinking into deep waters off the coast of Fiji whilst conducting a training flight. The sinking resulted in the deaths of two soldiers - one pilot from the 5th Aviation Regiment, and one trooper from the SASR.[245][246]

- On 10 March 2015, a UH-60 from Eglin Air Force Base crashed off the coast of the Florida Panhandle near the base. All eleven on board were killed.[247]

- On 16 February 2018, UH-60M helicopter deployed by the Mexican Air Force to Oaxaca after an earthquake, crashed into a group of people while attempting to land.[248][249]

- On 2 January 2020, a UH-60M helicopter of the Republic of China Air Force (ROCAF) in Taiwan, crashed on a mountainside, killing eight people on board, including General Shen Yi-ming, chief of the general staff of Republic of China's armed forces.[250]

- On 23 June 2021, a Philippine Air Force S-70i crashed in Capas town in Tarlac during a night flight training, killing all 6 crew members. The unit was newly delivered in November of the previous year or only almost 8 months old.[251]

- On 22 February 2022, two Utah National Guard Black Hawk helicopters crashed at the Snowbird, Utah ski resort during a training exercise. One Black Hawk was overcome by whiteout conditions caused by the downdraft in the snow, and crashed, causing parts of the rotor blades to strike the other helicopter, forcing a hard landing. There were no major injuries to the crew or skiers.[252]

- On July 16, 2022, one Mexican Navy Black Hawk crashed at Sinaloa, killing 14 marines on board.[253]

- In September 2022, a Black Hawk operated by the Taliban crashed during a training exercise in Kabul, killing three.[254]

- On February 15, 2023, a Black Hawk crashed killing two members of the Tennessee National Guard in Huntsville, Alabama.[255]

- On 29 March 2023, two US Army Black Hawk medical helicopters crashed during a training mission over Kentucky. All nine soldiers aboard were killed. The cause of the crash is under investigation.[256][257]

- On 10 November 2023, a US Army Black Hawk crashed off the coast of Cyprus in the Mediterranenan Sea. All 5 soldiers aboard were killed.[258]

Specifications (UH-60M)

[edit]

Data from Encyclopedia of Modern Warplanes,[259] International Directory,[260] Tomajczyk,[261] U.S. Army,[262] Lockheed-Martin brochure[263] General Electric T700-GE-701D Brochure[264]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2 pilots + 2 crew chiefs/gunners

- Capacity: 3,190 lb (1,450 kg) of cargo internally, including 11 seated troops or 6 stretchers, or 9,000 lb (4,100 kg) of cargo externally

- Length: 64 ft 10 in (19.76 m) including rotors

- Fuselage length: 50 ft 1 in (15.27 m)

- Width: 7 ft 9 in (2.36 m)

- Height: 16 ft 10 in (5.13 m)

- Empty weight: 12,511[263] lb (5,675 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 22,000[263] lb (9,979 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × General Electric T700-GE-701C/D turboshaft engines, 1,902 shp (1,418 kW) each

- Main rotor diameter: 53 ft 8 in (16.36 m)

- Main rotor area: 2,260 sq ft (210 m2) * Blade section: root: Sikorsky SC2110; tip: Sikorsky SSC-A09[263]

Performance

- Maximum speed: 159 kn (183 mph, 294 km/h)

- Cruise speed: 152 kn (175 mph, 282 km/h) maximum range at 18,000 lb[citation needed]

- Never exceed speed: 193 kn (222 mph, 357 km/h)

- Combat range: 320 nmi (370 mi, 590 km)

- Ferry range: 1,199 nmi (1,380 mi, 2,221 km) with ESSS stub wings and external tanks[261]

- Service ceiling: 19,000 ft (5,800 m)

- Rate of climb: 1,646 ft/min (8.36 m/s)

- Disk loading: 7.19 lb/sq ft (35.1 kg/m2)

- Power/mass: 0.192 shp/lb (0.316 kW/kg)

Armament

- Guns:

- 2 × 7.62 mm (0.30 in) M240 machine guns[265] or

- 2 × 7.62 mm (0.30 in) M134 minigun[261] or

- 2 × 12.7 mm (0.50 in) GAU-19 gatling guns[261]

- Hardpoints: 4, 2 per ESSS stub wings , with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Rockets: 70 mm (2.75 in) Hydra 70 unguided rockets in either a 7 tube (M260) or 19 tube (M261) pod.[261]

- Missiles: Up to 4x AGM-114 Hellfire laser guided air-to-ground missiles or 2x AIM-92 Stinger heat seeking air-to-air missiles per hardpoint. The Hellfire launcher rails can also be equipped with M260 (7 tube) Hydra pods.[172][261]

- Other: 7.62 mm (0.30 in), 12.7 mm (0.50 in), 20 mm (0.787 in), or 30 mm (1.18 in) M230 gun pods[261]

- Bombs: Can be equipped with VOLCANO minefield dispersal system.[261] See UH-60 Armament Subsystems for more information.

See also

[edit]

- Black Hawk Down – 2001 war film by Ridley Scott

- Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft - UH-60 replacement[266]

Related development

- Sikorsky S-70 – (United States)

- Sikorsky HH-60 Pave Hawk – (United States)

- Sikorsky HH-60 Jayhawk – (United States)

- Sikorsky SH-60 Seahawk – (United States)

- Piasecki X-49 SpeedHawk – (United States)

- Sikorsky S-92 / Sikorsky CH-148 Cyclone – (United States)

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- AgustaWestland AW149 – (Italy)

- Airbus Helicopters H175 – (France, China)

- Bell CH-146 Griffon – (United States)

- Bell UH-1 Iroquois – (United States)

- Bell UH-1N Twin Huey – (United States)

- Bell UH-1Y Venom – (United States)

- Bell 525 Relentless – (United States)

- Boeing Vertol YUH-61 – (United States)

- Denel Oryx – (South Africa)

- Eurocopter AS532 Cougar – (France)

- Harbin Z-20 – (China)

- KAI KUH-1 Surion – (South Korea)

- Mil Mi-8 /Mil Mi-17 – (Soviet Union, Russia)

- NHIndustries NH90 – (France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands)

Related lists

- List of helicopters

- List of utility helicopters

- List of active military aircraft of the United States

- List of Sikorsky S-70 Models

- List of military electronics of the United States

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ According to an Army Times article, "During the 1990s U.S. Special Operations Command worked with the Lockheed Martin Skunk Works division, which also designed the F-117, to refine the radar-evading technology and apply it to the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment's MH-60s," [a retired special operations aviator] said. USSOCOM awarded a contract to Boeing to modify several MH-60s to the low-observable design "in the '99 to 2000 timeframe," he also said.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Ryan Finnerty (23 January 2023). "Sikorsky delivers 5,000th Black Hawk, with potential for new US orders". Flightglobal.

- ^ Leoni 2007, pp. 8–10.

- ^ Leoni 2007, pp. 11, 39.

- ^ Leoni 2007, pp. 39, 42–43.

- ^ Leoni 2007, pp. 42–48.

- ^ Leoni 2007, p. 165.

- ^ Eden, Paul. "Sikorsky H-60 Black Hawk/Seahawk", Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. Amber Books, 2004. ISBN 1-904687-84-9.

- ^ Tomajczyk 2003, pp. 15–29.

- ^ a b Leoni 2007, pp. 217–18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bishop 2008.

- ^ "Pentagon Acquisition Panel Authorizes UH-60M Black Hawk Low Rate Initial Production". Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Sikorsky Aircraft, 4 April 2005.

- ^ Leoni 2007, pp. 233–36.

- ^ "Sikorsky Aircraft Delivers First New Production UH-60M Black Hawk Helicopter to U.S. Army". Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Sikorsky Aircraft, 31 July 2006.

- ^ a b c "UH-60 Black Hawk Sikorsky S-70A – Multi-Mission Helicopter." Archived 9 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine Army-Technology.com. Retrieved 24 October 2012. [unreliable source?]

- ^ "Sikorsky Aircraft Delivers 100th New Production UH-60M BLACK HAWK Helicopter to U.S. ..." Archived 5 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine Reuters, 25 March 2009.

- ^ Parsons, Dan (19 November 2014). "US awards Sikorsky $1.3 billion in helicopter contracts". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 19 November 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- ^ "US used never-seen-before stealth helicopters for Osama raid." Archived 6 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine ndtv.com, 5 May 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ a b Ross, Brian, Rhonda Schwartz, Lee Ferran and Avni Patel. "Top Secret Stealth Helicopter Program Revealed in Osama Bin Laden Raid: Experts." Archived 5 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine ABC World News, 4 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d Naylor, Sean D. "Army mission helicopter was secret, stealth Black Hawk". Army Times, 4 May 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ "Structural Concepts and Aerodynamic Analysis for Low Radar Cross Section (LRCS) Fuselage Configurations". Archived 17 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine DTIC. Retrieved: 23 August 2011.

- ^ "Sikorsky awarded contract to integrate and test enhanced Black Hawk helicopter capabilities". Archived 2 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Sikorsky press release, 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Future Vertical Lift: Have Plan, Need Money" Archived 25 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Aviation today, 1 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Adding new punch to aerial deliveries" Archived 12 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Army, 16 August 2013

- ^ a b "Picatinny 'Speed Bag' resupplies Soldiers with less equipment damage" Archived 26 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Army, 25 June 2014

- ^ a b The enhanced speed bag system Archived 19 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Army, 7 July 2015

- ^ a b Harding, Stephen. "Sikorsky H-60 Black Hawk". U.S. Army Aircraft Since 1947. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 1997. ISBN 0-7643-0190-X.

- ^ Leoni 2007

- ^ "Weapons and Ordnance – PS106IS Primer (v 1.0)" (PDF). ucsd.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ "Preliminary Airworthiness Eval of UH-60A Configured with ESSS." Archived 4 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine US DoD. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ "H-60 Black Hawk Crashworthy External Fuel System (CEFS)" (PDF). Robertson Fuel Systems. July 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2013. [permanent dead link]

- ^ "Preliminary Airworthiness Eval of UH-60A/ESSS with Hellfire Missile Launcher Installed." Archived 4 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine DTIC.mil. Retrieved: 24 October 2012.

- ^ "Greece to Purchase 35 UH-60M Black Hawks Through FMS". GBP. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Sikorsky S70A-9 Black Hawk Helicopter" (PDF). Boeing. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ Leoni 2007, p. 253.

- ^ Department of Defence (1988). Defence Report 1987-88. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. pp. vi, 28. ISBN 064407891X. Archived from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "5th Aviation Regiment". Australian Army. Archived from the original on 27 February 2012.

- ^ Australian Army Flying Museum (2015). "Army aviation in Australia 1970–2015" (PDF). Australian Army. pp. 6, 7, 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2016.

- ^ Cleary, Paul (29 November 2014). "Combat choppers denied". The Australian. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "AIR 5416 - Project Echidna Electronic Warfare Self Protection for ADF Aircraft". Department of Defence. Defence Material Organisation. 24 November 2008. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- ^ The Auditor-General (2014). Multi-Role Helicopter Program (PDF). Audit Report No.52 2013–14. Canberra: Australian National Audit Office. pp. 16, 98–101, 107. ISBN 978-0642814975. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ The Auditor-General 2014, p. 84.

- ^ Coppinger, Bob (4 April 2021). "ARMY & RAAF A25 Sikorsky S70-A9 Black Hawk". ADF-Serials. Archived from the original on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Kerr, Julian (1 February 2016). "Air: MRH90 Taipan – reaching for 2016 milestones". Australian Defence Magazine. Archived from the original on 20 March 2024. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ Kerr, Julian (1 December 2015). "Australian Army to extend Black Hawk service lives for special forces use". Jane's Defence Weekly. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016.

- ^ a b McLaughlin, Andrew (10 December 2021). "With a new Black Hawk on the way, the original is retired". Australian Defence Business Review. Archived from the original on 20 March 2024. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ Minister for Defence Peter Dutton (10 December 2021). "Strengthening Army's helicopter capability". Department of Defence Ministers (Press release). Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "Black Hawk helicopters for Defence". Department of Defence (Press release). 18 January 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ "Brazil Buys UH-60L Black Hawks". Defense Industry Daily. 9 September 2012. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ a b Leoni 2007, pp. 286-292.

- ^ Leoni 2007, pp. 270–273.

- ^ Arpía Archived 3 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine. SpanishDict.com. Retrieved 30 September 2009. "Arpía [ar-pee'-ah] noun 1. (Poetic.) Harpy, a bird of prey represented by poets. (f)"

- ^ a b "SIKORSKY -Colombia Takes Delivery of First S-70i BLACK HAWK Helicopters with Terrain Awareness and Warning Capability". HispanicBusiness.com. 21 October 2013. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ a b c Leoni 2007, pp. 278–279.

- ^ "Sikorsky UH-60 / S-70 Blackhawk (Yanshuf)." Archived 3 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine Jewish Virtual Library Retrieved: 18 November 2013.

- ^ "Aztec Rotors – Helicopters of Mexican Air Force". acig.org. Archived from the original on 22 June 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ "Mexico sends 1,000 more police to drug area". NBC News. 16 July 2009. Archived from the original on 20 March 2024. Retrieved 26 September 2009.

- ^ "Mexican police arrest 34 drug cartel suspects". CNN. 3 August 2009. Archived from the original on 7 August 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2009.

- ^ "Blackhawks ready to fly for the Mexican Navy". app.com. 25 August 2011.

- ^ "Major Arms Sales". dsca.mil. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ "Sikorsky's $8.5-11.7B "Multi-Year 8" H-60 Helicopter Contract". Defense Industry Daily. 18 March 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ "Static Display: Philippine Air Force showcases Black Hawk and HU-1 at old Bacolod airport". Bacolod City Government. 15 October 2023. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ "Philippines orders 16 Sikorsky S-70i Black Hawk utility helicopters". Asia Pacific Defense Journal. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ "PH Air Force boosts fleet with first batch of new Black Hawk choppers". Philippine Daily Inquirer. 10 December 2020. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "Philippine Air Force receives five more S-70i Black Hawk helicopters". Airforce-technology.com. 9 June 2021.

- ^ a b Nepomuceno, Priam (9 November 2021). "Delivery of 'Black Hawk' choppers now complete: PAF". Philippine News Agency. PH. Archived from the original on 21 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Philippines signs $624 million deal to purchase 32 Black Hawk helicopters". Business Standard. 22 February 2022. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "Additional S-70i Blackhawk Helicopters for the Philippine Air Force?". Pitz Defense Analysis. 5 December 2021. Archived from the original on 5 December 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ "S-70i Black Hawk: Philippines Set To Become World's Largest Operator Of US Choppers; To Add 32 News Helos". The Eurasian Times. 12 March 2024. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "Poland Purchases Four New S-70i Black Hawk Helicopters". Overtdefense.com. 17 December 2021. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ Jennings, Gareth (21 July 2023). "Poland launches Black Hawk helo tender". Janes. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ "Slovakia – UH-60M Black Hawk Helicopters". Defense Security Cooperation Agency. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "State OK's Slovakia UH-60 Deal". Defense News, 20 February 2015.

- ^ "Slovakia considering US Black Hawk offer". Janes.com. 14 January 2015. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ [1] Archived 22 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine Jane's

- ^ "Contracts for September 3, 2015". Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ "Slovakia shows off new Black Hawk". 6 September 2017. Archived from the original on 7 September 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ TeamAirsoc. "SLOVAKIA SHOWS OFF NEW BLACK HAWK".

- ^ "Exclusive shots: The last three new Black Hawks from America landed in Presov". tvnoviny.sk. 11 January 2020.

- ^ "Naď: Ponuku od USA plánujeme využiť na vrtuľníky Black Hawk a ich výbavu". HN Slovensko. 20 December 2020.

- ^ "Afghan Black Hawk Pilots Training in Slovakia". Helis.com.

- ^ "Sweden makes surprise Black Hawk request". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 5 December 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "Sweden Ordering H-60M Helicopters for Afghan CSAR/MEDEVAC". Defense Industry Daily. 16 July 2012. Archived from the original on 5 May 2011.

- ^ av: Lasse Jansson. "Helikopter 16 på väg till Afghanistan - Försvarsmakten". Forsvarsmakten.se. Archived from the original on 18 April 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ "Sverige köper 15 Black Hawk-helikoptrar". Expressen. 9 April 2011. Archived from the original on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2011. (English translation) Archived 2 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ https://www.fmv.se/aktuellt--press/aktuella-handelser/bestallning-av-tolv-helikoptrar/

- ^ "ROCAF Sikorsky S-70C Bluehawk". Taiwanairpower.org. 11 November 2008. Archived from the original on 27 February 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ "Sikorsky S-70C(M) Thunderhawk". Taiwanairpower.org. April 2008. Archived from the original on 5 June 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ Govindasamy, Siva (31 January 2010). "USA okays Black Hawks for Taiwan, Beijing mulls sanctions". Flight International. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ "52 Black Hawk helicopters grounded after fatal crash". Taiwanairpower.org. 2 January 2020. Archived from the original on 20 March 2024. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "Turkey to decide in June between AW149, 'T-70' Black Hawk". Flight International. 9 April 2009. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ "TAI to procure more helicopters for security". Today's Zaman. 6 April 2009. [permanent dead link]

- ^ "Milyarlık helikopter ihalesi Skorsky'nin". Istanbulhaber. 21 April 2011. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ "Turkey Picks Sikorsky Helo in $3.5B Deal". Defense News. 21 April 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2011. [dead link]

- ^ "Sikorsky wins Turkish utility helicopter battle". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ^ "Turkish Soldiers Fly To Greece For Asylum". Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ^ "Turkey coup attempt: Greek dilemma over soldiers who fled". BBC. 19 July 2016. Archived from the original on 25 August 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ a b D'Urso, Stefano. "Ukraine Is Now Using At Least Two UH-60 Black Hawk Helicopters". theaviationist.com. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ D'Urso, Stefano. "First (And Only) Ukrainian Black Hawk Seen In Action". theaviationist.com. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ TYSHCHENKO, KATERYNA. "Ukraine's Defence Intelligence refutes Russians' reports about "downing" Black Hawk helicopter". Ukrainska Pravda. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ Goebel, Greg. "S-70 Origins: UTTAS". Air Vector. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ^ "Black Hawks." Archived 25 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine armyaircrews.com. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Page, Lewis. "Sikorsky, US Army claim whisper-flapcopter test success." Archived 10 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Register, 5 May 2011.

- ^ "Political punch: Obama gives order, Bin Laden is killed; White House time line." Archived 10 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine ABC News, May 2011.

- ^ a b "Bin Laden raid: China 'viewed US helicopter wreckage'". BBC. 15 August 2011. Archived from the original on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ a b c "Reports: Pakistan let Chinese inspect U.S. stealth copter." Archived 18 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine CNN, 15 August 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ "Report: Pakistan Granted China Access to U.S.'s Top-Secret Bin Laden Raid Chopper." Archived 6 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine Fox News Channel, 15 August 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ Capaccio, Anthony; Tiron, Roxana (5 December 2022). "US Army Taps Bell Textron for Helicopter of the Future". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2023. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Weisgerber, Marcus (5 December 2022). "Army Chooses Bell V-280 to Replace Its Black Hawk Helicopters". Defense One. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ "United Arab Emirates – UH-60M Black Hawk Helicopters" (PDF). US Defense Security Cooperation Agency. 9 September 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2011.

- ^ "Dubai Helishow: UAE increases Black Hawk fleet". Rotorhub. 2 November 2010. Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ "Selected Acquisition Report - UH-60M Black Hawk" (PDF). US Department of Defense. 31 December 2011. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2012.

- ^ "Conventional Arms Transfers to Developing Nations, 2003-2010" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ "Brunei receives first S-70i helicopters". IHS Jane's Defence Weekly. 4 December 2013. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ "Qatar – UH-60M Black Hawk Helicopters" (PDF). US Defense Security Cooperation Agency. 13 June 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ a b Abas, Marhalim (23 January 2015). "RMAF getting Brunei Blackhawks". Malaysian Defence. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "black Hawke". jutarnji.hr. Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Predstavljeni helikopteri Black Hawk UH-60M". morh.hr. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ Jennings, Gareth (31 October 2019). "Croatia cleared to buy Black Hawks". JANES.

- ^ "BREAKING NEWS – RH kupuje dodatne Black Hawk helikoptere!". Obris.org. 31 October 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ "Croatia welcomes lead pair of UH-60M Black Hawk helicopters". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ "The U.S. Delivers UH-60M Black Hawk Helicopters Valued at 360 Million Kuna in Latest U.S. Defense Contribution to Croatia". U.S. Embassy in Croatia. 3 February 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ "Croatia – UH-60M Black Hawk Helicopters". dsca.mil. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ Mladen (13 March 2024). "Helikopteri Black Hawk dokaz snažnog partnerstva Hrvatske i SAD-a". MORH (in Croatian). Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ Mladen (23 February 2024). "Odbor za obranu jednoglasno za postupak nabave Black Hawkova". MORH (in Croatian). Retrieved 23 February 2024.

- ^ "Tunisia – UH-60M Black Hawk Helicopters" Archived 27 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine. DSCA, 24 July 2014.

- ^ [2] Archived 19 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine tap.info.tn

- ^ "Tunisia completes Black Hawk purchase | Times Aerospace". timesaerospace.aero. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ [3] Archived 6 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine. DSCA

- ^ "Latvia gets its first 'Black Hawk' helicopters". eng.lsm.com. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ "Lithuania to purchase UH-60M Black Hawk helicopters from US". 20 October 2019.

- ^ "Lithuania signs deal for its first American military helicopters". 16 November 2020.

- ^ "Lithuania – UH-60M Black Hawk Helicopters". dsca.mil. 6 July 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ "Lithuania and the U.S. signed a contract on procurement of a new UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter platform from the U.S. Government". kam.lt. 13 November 2020. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ Adamowski, Jaroslaw (16 November 2020). "Lithuania signs deal for its first American military helicopters". Defense News. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ "Lithuanian Partners Complete U.S. Army Flight Course". National Guard. Retrieved 6 April 2024.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Helicopter maintenance hangar opened at Siauliai Air Force Base in Lithuania". www.baltictimes.com. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ "Four Black Hawk Helicopters for Poland By the End of 2019". defence24.com. 25 January 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- ^ Bisht, Inder Singh (25 July 2023). "Poland Initiates Black Hawk Helicopter Purchase Negotiations". The Defense Post. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ "Um dos seis helicópteros UH-60 adquiridos pela Força Aérea realizou o primeiro voo, no Alabama". twitter.com. 17 August 2023. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ Giovanni (18 December 2023). "Portuguese Air Force Begins Flying Its New Black Hawk Helicopters". Defense aerospace. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ "New helicopters for Hellenic Air Force and Army". scramble.nl. Scramble. 18 December 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "Greece – UH-60M Black Hawk Helicopters Defense Security Cooperation Agency". www.dsca.mil. 15 December 2023. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ "US approves UH-60Ms for Greece". Janes.com. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ a b Martin, Tim (8 April 2024). "Greece formally agrees to nearly $2 billion UH-60M Black Hawk helicopter deal". Breaking Defense. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ DefenceSpace (12 April 2024). "Greece Moves Forward In Procurement of UH-60M Black Hawk". Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ "Indonesia to purchase UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters". Airrecognition.com. 26 February 2013. Archived from the original on 21 August 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ "Indonesia to buy Boeing's F-15 jets, Lockheed's Black Hawk helicopters". DefenseNews.

- ^ "After F-15 Jets, Indonesia Buys 24 Sikorsky Black Hawk Helicopters". The Defense Post.

- ^ Dunlop, Tom (13 December 2021). "Black Hawk helicopters offered to UK as Puma replacement". Uk Defence Journal.

- ^ "Black Hawk." Archived 14 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Army Fact Files. Retrieved: 2 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n DoD 4120-15L, "Model Designation of Military Aerospace Vehicles," Archived 25 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine DoD, 12 May 2004.

- ^ a b "Sikorsky S-70 (H-60) Upgrades". (online subscription article) Jane's Aircraft Upgrades, 16 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d Donald, David, ed. "Sikorsky S-70". The Complete Encyclopedia of World Aircraft. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997. ISBN 0-7607-0592-5.

- ^ Leoni 2007, pp. 217–224.

- ^ "SNC Submits Sierra Force™ Helicopter in Final Bid for UH-1N Replacement Program" (Press release). Sierra Nevada Corporation. 23 July 2018. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ Leoni 2007, pp. 233–44.

- ^ "Sikorsky Aircraft Fully Equips First U.S. Army Unit With UH-60M BLACK HAWK Helicopters." Archived 25 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Sikorsky Aircraft, 10 June 2008.

- ^ "Sikorsky's UH-60M Upgrade Black Hawk Helicopter Achieves First Flight." Archived 27 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine Sikorsky, 29 August 2008.

- ^ "Northrop To Upgrade U.S. Army UH-60L Cockpits", Aviation week, 15 August 2014, archived from the original on 19 August 2014, retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ a b Colucci, Frank. "Modern Medevac Mobilized." Archived 25 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine Rotor & Wing, 1 October 2004.

- ^ Leoni 2007, p. 224.

- ^ "HH-60M Medevac Helicopter." Archived 19 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine Sikorsky. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ "Sikorsky pitches HH-60Us to replace USAF Hueys", FlightGlobal, 28 February 2017, archived from the original on 7 March 2017, retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ^ "'Whiskey' to perform personnel recovery mission" Archived 29 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine. AF, 24 November 2014.

- ^ "USAF's first HH-60W Jolly Green II arrives at Moody AFB". Air Force. 6 November 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Tomajczyk 2003, pp. 21–23.

- ^ a b Bishop 2008, pp. 20, 22.

- ^ Tomajczyk 2003, p. 23.

- ^ a b c Tomajczyk 2003, pp. 23–26.

- ^ MH-60 Black Hawk fact sheet, 160th SOAR, archived from the original on 31 October 2010

- ^ "160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (Airborne)". US Army Special Operations Command. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ^ a b "MH-60L DAP". American special ops. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ a b Tomajczyk 2003, pp. 26–29.

- ^ "Sikorsky S-70A/H-60." [permanent dead link] (online subscription article) Jane's Helicopter Markets and Systems, 31 March 2011.

- ^ "Sikorsky S-70 (H-60) – US Army MH-60 Upgrades" (online subscription article). [permanent dead link] Jane's Aircraft Upgrades, 2008, 11 June 2008.

- ^ "Sikorsky S-70 (H-60) Upgrades" (online subscription article). [permanent dead link] Jane's Aircraft Upgrades, 3 May 2011.