| ||

|---|---|---|

Media gallery |

||

|

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Ba'athism |

|---|

|

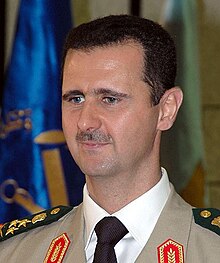

Bashar al-Assad[a][b] (born 11 September 1965) is a Syrian politician who is the current and 19th president of Syria since 17 July 2000. In addition, he is the commander-in-chief of the Syrian Armed Forces and the secretary-general of the Central Command of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party, which nominally espouses a neo-Ba'athist ideology. His father and predecessor was General Hafiz al-Assad, whose presidency in 1971–2000 marked the transfiguration of Syria from a republican state into a de facto dynastic dictatorship, tightly controlled by an Alawite-dominated elite composed of the armed forces and the Mukhabarat (secret services), who are loyal to the al-Assad family.

Born and raised in Damascus, Bashar graduated from the medical school of Damascus University in 1988 and began to work as a doctor in the Syrian Army. Four years later, he attended postgraduate studies at the Western Eye Hospital in London, specialising in ophthalmology. In 1994, after his elder brother Bassel died in a car accident, Bashar was recalled to Syria to take over Bassel's role as heir apparent. He entered the military academy, taking charge of the Syrian occupation of Lebanon in 1998. On 17 July 2000, Bashar al-Assad became president, succeeding his father Hafiz, who had died on 10 June 2000. A series of crackdowns in 2001–02 ended the Damascus Spring, a period of cultural and political activism marked by calls for transparency and democracy. Although Bashar inherited the power structures and personality cult nurtured by Hafiz al-Assad, he lacked the loyalty received by his father, which led to rising discontent against his rule. As result, many members of the Old Guard resigned or were purged; and the inner-circle were replaced by staunch loyalists from Alawite clans. Bashar al-Assad's early economic liberalisation programs worsened inequalities and centralized the socio-political power of the loyalist Damascene elite of the Assad family; alienating the Syrian rural population, urban working classes, businessmen, industrialists and people from once-traditional Ba'ath strongholds. The Cedar Revolution in Lebanon in February 2005, triggered by the assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, forced Bashar al-Assad to end Syrian occupation of Lebanon.

Assad's regime is a highly personalist dictatorship,[c] which governs Syria as a totalitarian police state.[d] Bashar al-Assad's reign has been characterised by numerous human rights violations and severe repression. While the Assad government describes itself as secular, various political scientists and observers note that his regime exploits sectarian tensions in the country. The first decade in power was marked by intense censorship, summary executions, forced disappearances, discrimination of ethnic minorities and extensive surveillance by the Ba'athist secret police. The United States, the European Union, and majority of the Arab League called for Assad's resignation from the presidency in 2011 after he ordered a violent crackdown on Arab Spring protesters during the events of the Syrian revolution, which led to the Syrian civil war. The civil war has killed around 580,000 people, of which a minimum of 306,000 deaths are non-combatant, with pro-Assad forces causing more than 90% of the civilian deaths.[7] The war has also forcibly displaced 14 million Syrians, with over 7 million refugees, causing the largest refugee crisis in the world. An additional 154,000 civilians have been forcibly disappeared or subject to arbitrary detentions; with over 135,000 individuals being tortured, imprisoned, or dead in government detention centres as of 2023.[e]

The Assad regime's perpetration of numerous war crimes and crimes against humanity during the civil war has led to international condemnation and isolation.[f] The Syrian military is estimated to have conducted over 300 chemical attacks, with UN investigations confirming at least nine chemical attacks conducted by pro-Assad forces.[13] The deadliest incident was a chemical attack in Ghouta on 21 August 2013, which caused the deaths of 1,100–1,500 civilians. In December 2013, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay stated that findings from an inquiry by the UN implicated Assad in war crimes. Investigations by the OPCW-UN Joint Investigative Mechanism and OPCW-UN IIT concluded that the Assad government was responsible for the 2017 Khan Shaykhun sarin attack and 2018 Douma chemical attack respectively.[g] In June 2014, the American Syrian Accountability Project included Assad on a list of war crimes indictments of government officials and sent it to the International Criminal Court. In 2023, Canada and the Netherlands filed a joint lawsuit at the International Court of Justice accusing the Assad government of infringing UN Convention Against Torture.[h] On 15 November 2023, France issued an arrest warrant against Assad over the use of banned chemical weapons against civilians in Syria.[14] Assad has categorically denied the allegations of these charges and has accused foreign countries, especially the American-led intervention in Syria, of purportedly attempting regime change.[15][16]

|

Further information: Al-Assad family |

Bashar al-Assad was born in Damascus on 11 September 1965, as the second son and third child of Anisa Makhlouf and Hafiz al-Assad.[17] "Al-Assad" in Arabic means "the lion". Assad's paternal grandfather, Ali Sulayman al-Assad, had managed to change his status from peasant to minor notable and, to reflect this, in 1927 he had changed the family name from "Wahsh" (meaning "Savage") to "Al-Assad".[18]

Assad's father, Hafiz, was born to an impoverished rural family of Alawite background and rose through the Ba'ath Party ranks to take control of the Syrian branch of the Party in the Corrective Movement, culminating in his rise to the Syrian presidency.[19] Hafiz promoted his supporters within the Ba'ath Party, many of whom were also of Alawite background.[17][20] After the revolution, Alawite strongmen were installed while Sunnis, Druze, and Ismailis were removed from the army and Ba'ath party.[21] Hafiz al-Assad's 30-year military rule witnessed the transformation of Syria into a dynastic dictatorship. The new political system was led by the Ba'ath party elites dominated by the Alawites, who were fervently loyal to the Assad family and controlled the military, security forces and secret police.[22][23]

The younger Assad had five siblings, three of whom are deceased. A sister named Bushra died in infancy.[24] Assad's youngest brother, Majd, was not a public figure and little is known about him other than he was intellectually disabled,[25] and died in 2009 after a "long illness".[26]

Unlike his brothers Bassel and Maher, and second sister, also named Bushra, Bashar was quiet, reserved and lacked interest in politics or the military.[27][25][28] The Assad children reportedly rarely saw their father,[29] and Bashar later stated that he only entered his father's office once while he was president.[30] He was described as "soft-spoken",[31] and according to a university friend, he was timid, avoided eye contact and spoke in a low voice.[32]

Assad received his primary and secondary education in the Arab-French al-Hurriya School in Damascus.[27] In 1982, he graduated from high school and then studied medicine at Damascus University.[33]

In 1988, Assad graduated from medical school and began working as an army doctor at the Tishrin Military Hospital on the outskirts of Damascus.[34][35] Four years later, he settled in London to start postgraduate training in ophthalmology at the Western Eye Hospital.[36] He was described as a "geeky I.T. guy" during his time in London.[37] Bashar had few political aspirations,[38] and his father had been grooming Bashar's older brother Bassel as the future president.[39] However, he died in a car accident in 1994 and Bashar was recalled to the Syrian Army shortly thereafter. State propaganda soon began elevating Bashar's public imagery as "the hope of the masses" to prepare him as the next patriarch in charge of Syria, to continue the rule of the Assad dynasty.[40][41]

Soon after the death of Bassel, Hafiz al-Assad decided to make Bashar the new heir apparent.[42] Over the next six and a half years, until his death in 2000, Hafiz prepared Bashar for taking over power. General Bahjat Suleiman, an officer in the Defense Companies, was entrusted with overseeing preparations for a smooth transition,[43][29] which were made on three levels. First, support was built up for Bashar in the military and security apparatus. Second, Bashar's image was established with the public. And lastly, Bashar was familiarised with the mechanisms of running the country.[44]

To establish his credentials in the military, Bashar entered the military academy at Homs in 1994 and was propelled through the ranks to become a colonel of the elite Syrian Republican Guard in January 1999.[34][45][46] To establish a power base for Bashar in the military, old divisional commanders were pushed into retirement, and new, young, Alawite officers with loyalties to him took their place.[47]

In 1998, Bashar took charge of Syria's Lebanon file, which had since the 1970s been handled by Vice President Abdul Halim Khaddam, who had until then been a potential contender for president.[47] By taking charge of Syrian affairs in Lebanon, Bashar was able to push Khaddam aside and establish his own power base in Lebanon.[48] In the same year, after minor consultation with Lebanese politicians, Bashar installed Emile Lahoud, a loyal ally of his, as the President of Lebanon and pushed former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri aside, by not placing his political weight behind his nomination as prime minister.[49] To further weaken the old Syrian order in Lebanon, Bashar replaced the long-serving de facto Syrian High Commissioner of Lebanon, Ghazi Kanaan, with Rustum Ghazaleh.[50]

Parallel to his military career, Bashar was engaged in public affairs. He was granted wide powers and became head of the bureau to receive complaints and appeals of citizens, and led a campaign against corruption. As a result of this campaign, many of Bashar's potential rivals for president were put on trial for corruption.[34] Bashar also became the President of the Syrian Computer Society and helped to introduce the internet in Syria, which aided his image as a moderniser and reformer. Ba'athist loyalists in the party, military and the Alawite sect were supportive of Bashar al-Assad, enabling him to become his father's successor.[51]

|

Further information: Foreign Policy of Bashar al-Assad |

After the death of Hafiz al-Assad on 10 June 2000, the Constitution of Syria was amended. The minimum age requirement for the presidency was lowered from 40 to 34, which was Bashar's age at the time.[52] Assad contested as the only candidate and subsequently confirmed president on 10 July 2000, with 97.29% support for his leadership.[53][54][55] In line with his role as President of Syria, he was also appointed the commander-in-chief of the Syrian Armed Forces and Regional Secretary of the Ba'ath Party.[51] A series of state elections have since been held regularly every seven years which Assad won with overwhelming majority of votes. The elections are unanimously regarded by independent observers as a sham process and boycotted by the opposition.[i][j] The last two elections - held in 2014 and 2021 - were conducted only in areas controlled by the Syrian government during the country's ongoing civil war and condemned by the United Nations.[65][66][67]

|

See also: Damascus Spring |

Immediately after he took office, a reform movement known as Damascus Spring led by writers, intellectuals, dissidents, cultural activists, etc. made cautious advances, which led to the shut down of Mezzeh prison and the declaration of a wide-ranging amnesty releasing hundreds of Muslim Brotherhood affiliated political prisoners.[68] However, security crackdowns commenced again within the year, turning it into the Damascus Winter.[69][70] Hundreds of intellectuals were arrested, targeted, exiled or sent to prison and the state of emergency was continued. The early concessions were rolled back to tighten authoritarian control, censorship was increased and the Damascus Spring movement was banned under the pretext of "national unity and stability". The regime's policy of a "social market economy" became a symbol of corruption, as Assad loyalists became its sole beneficiaries.[51][71][72][73] Several discussion forums were shut down and many intellectuals were abducted by the Mukhabarat to get tortured and killed. Many analysts believe that initial promises of opening up were part a government strategy to find out Syrians who were not supportive of the new leadership.[70]

During a state visit by British Prime Minister Tony Blair to Syria in October 2001, Bashar publicly condemned the United States invasion of Afghanistan in a joint press conference, stating that "[w]e cannot accept what we see every day on our television screens - the killing of innocent civilians. There are hundreds dying every day." Assad also praised Palestinian militant groups as "freedom fighters" and criticised Israel and the Western world during the conference. British officials subsequently described Assad's political views as being more conciliatory in private, claiming that he criticized the September 11 attacks and accepted the legitimacy of the State of Israel.[74]

During the war on terror, Assad played realpolitik with the United States, at-times co-operating and other times clashing with the American government. Syria's prison networks were a major site of extraordinary rendition by the CIA of al-Qaeda suspects, who were interrogated in Syrian prisons.[75][76][77] Soon after Assad assumed power, he "made Syria's link with Hezbollah—and its patrons in Tehran—the central component of his security doctrine",[78] and in his foreign policy, Assad adopted a belligerent stance towards the U.S., Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey.[79] During the Iraqi insurgency against American occupation, Syrian intelligence trained Al-Qaeda militants, turning Syria into a transit hub for Jihadists travelling into Iraq. AQI would subsequently evolve into the Islamic State group, which sent its fighters from Iraq to join the Syrian Civil War.[80][81]

|

See also: Assassination of Rafic Hariri, Cedar Revolution, and Syrian occupation of Lebanon |

"It will be Lahoud.. opposing him is tantamount to opposing Assad himself.. I will break Lebanon over your head and over Walid Jumblatt's head. So you had better return to Beirut and arrange the matter on that basis."

— Assad's threats to Rafic Hariri in August 2004, over the issue of tenure extension of Syrian ally Emile Lahoud[82]

On 14 February 2005, Rafic Hariri, the former prime minister of Lebanon, was assassinated in a massive truck-bomb explosion in Beirut, killing 22 people. The Christian Science Monitor reported that "Syria was widely blamed for Hariri's murder. In the months leading to the assassination, relations between Hariri and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad plummeted amid an atmosphere of threats and intimidation."[83] Bashar promoted his brother-in-law Assef Shawkat, a key figure suspected of orchestrating the terrorist attack, as the chief of Syrian Military Intelligence Directorate immediately after Hariri's death.[84]

The killings caused massive uproar, triggering an intifada in Lebanon and hundreds of thousands of protestors poured on the streets to demand total withdrawal of Syrian military forces. After mounting international pressure that called Syria to implement the UNSC Resolution 1559, Bashar al-Assad declared on 5 March that he shall order the departure of Syrian soldiers. On 14 March 2005, more than a million Lebanese protestors - Muslims, Christians, Druze - demonstrated in Beirut, marking the monthly anniversary of Hariri's murder. UN Resolution 1595, adopted on 7 April, send an international commission to investigate the assassination of Hariri. By 5 May 2005, United Nations had officially confirmed the total departure of all Syrian soldiers, ending the 29-year old military occupation. The uprisings that occurred in these months came to be known as Lebanon's "independence intifada" or the "Cedar Revolution".[85]

UN investigation commission's report published on 20 October 2005 revealed that high-ranking members of Syrian intelligence and Assad family had directly supervised the killing.[86][87][88] The BBC reported in December 2005 that "Damascus has strongly denied involvement in the car bomb which killed Hariri in February".[89]

On 27 May 2007, Assad was approved for another seven-year term in a referendum on his presidency, with 97.6% of the votes supporting his continued leadership.[90][91][92] Opposition parties were not allowed in the country and Assad was the only candidate in the referendum.[55] Syria's opposition parties under the umbrella of Damascus Declaration denounced the elections as illegitimate and part of the regime's strategy to sustain the "totalitarian system".[93][94] Elections in Syria are officially designated as the event of "renewing the pledge of allegiance" to the Assads and voting is enforced as a compulsory duty on every citizen. Announcement of the results are followed by pro-government rallies conducted across the country extolling the regime, wherein citizens declare their "devotion" to the President and celebrate "the virtues" of the Assad dynasty.[95][96][97]

Syria began developing a covert nuclear weapons programme with assistance of North Korea during the 2000s, but its suspected nuclear reactor was destroyed by the Israeli Air Force during Operation Outside the Box in September 2007.[98][99][100]

|

See also: Arab Spring, 2011 Syrian Revolution, Syrian civil war, and Sanctions against Syria |

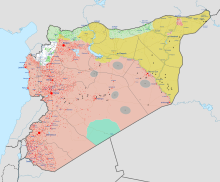

Protests in Syria began on 26 January 2011 following the Arab Spring protests that called for political reforms and the reinstatement of civil rights, as well as an end to the state of emergency which had been in place since 1963.[101] One attempt at a "day of rage" was set for 4–5 February, though it ended uneventfully.[102] Protests on 18–19 March were the largest to take place in Syria for decades, and the Syrian authority responded with violence against its protesting citizens.[103] In his first public response to the protests delivered on 30 March 2011, Assad blamed the unrest on "conspiracies" and accused the Syrian opposition and protestors of seditious "fitna", toeing the party-line of framing the Ba'athist state as the victim of an international plot. He also derided the Arab Spring movement, and described those participating in the protests as "germs" and fifth-columnists.[104][105][106]

"Throughout the speech, al-Assad remained faithful to the basic ideological line of Syrian Baathism: the binary opposition of a devilishly determined, conspiring ‘outside’ bent on hurting a heroically defending and essentially good ‘inside’... consistent with Baathist dualism, [the speech] makes the sparing, if not grudging, mention of supposedly minor dissent in this ‘inside’. This dissent loses its political meaning, or moral justification, acquiring ‘othering’ essence when the president places it in the dismissive context of the ‘fitna’... Following this hard-line speech, the protesters’ demands moved from reforming to overthrowing the regime."

— Professor Akeel Abbas on Assad's first public speech after the outbreak of Syrian Revolution protests[107]

The U.S. imposed limited sanctions against the Assad government in April 2011, followed by Barack Obama's executive order as of 18 May 2011 targeting Bashar Assad specifically and six other senior officials.[108][109][110] On 23 May 2011, the EU foreign ministers agreed at a meeting in Brussels to add Assad and nine other officials to a list affected by travel bans and asset freezes.[111] On 24 May 2011, Canada imposed sanctions on Syrian leaders, including Assad.[112]

On 20 June, in response to the demands of protesters and international pressure, Assad promised a national dialogue involving movement toward reform, new parliamentary elections, and greater freedoms. He also urged refugees to return home from Turkey, while assuring them amnesty and blaming all unrest on a small number of saboteurs.[113]

In July 2011, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said Assad had "lost legitimacy" as president.[109] On 18 August 2011, Barack Obama issued a written statement that urged Assad to "step aside".[114][115][116] In August, the cartoonist Ali Farzat, a critic of Assad's government, was attacked. Relatives of the humourist told media outlets that the attackers threatened to break Farzat's bones as a warning for him to stop drawing cartoons of government officials, particularly Assad. Farzat was hospitalised with fractures in both hands and blunt force trauma to the head.[117][118]

Since October 2011, Russia, as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, repeatedly vetoed Western-sponsored draft resolutions in the UN Security Council that would have left open the possibility of UN sanctions, or even military intervention, against the Assad government.[119][120][121]

By the end of January 2012, it was reported by Reuters that over 5,000 civilians and protesters (including armed militants) had been killed by the Syrian army, security agents and militia (Shabiha), while 1,100 people had been killed by "terrorist armed forces".[122]

On 10 January 2012, Assad gave a speech in which he maintained the uprising was engineered by foreign countries and proclaimed that "victory [was] near". He also said that the Arab League, by suspending Syria, revealed that it was no longer Arab. However, Assad also said the country would not "close doors" to an Arab-brokered solution if "national sovereignty" was respected. He also said a referendum on a new constitution could be held in March.[123]

On 27 February 2012, Syria claimed that a proposal that a new constitution be drafted received 90% support during the relevant referendum. The referendum introduced a fourteen-year cumulative term limit for the president of Syria. The referendum was pronounced meaningless by foreign nations including the U.S. and Turkey; the EU announced fresh sanctions against key regime figures.[124] In July 2012, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov denounced Western powers for what he said amounted to blackmail thus provoking a civil war in Syria.[125] On 15 July 2012, the International Committee of the Red Cross declared Syria to be in a state of civil war,[126] as the nationwide death toll for all sides was reported to have neared 20,000.[127]

On 6 January 2013, Assad, in his first major speech since June, said that the conflict in his country was due to "enemies" outside of Syria who would "go to Hell" and that they would "be taught a lesson". However, he said that he was still open to a political solution saying that failed attempts at a solution "does not mean we are not interested in a political solution."[128][129] In July 2014, Assad renewed his third term of presidency after voting process conducted in pro-regime territories which were boycotted by the opposition and condemned by the United Nations.[65][66][67] According to Joshua Landis: "He's (Assad) going to say: 'I am the state, I am Syria, and if the West wants access to Syrians, they have to come through me.'"[66]

After the fall of four military bases in September 2014,[130] which were the last government footholds in the Raqqa Governorate, Assad received significant criticism from his Alawite base of support.[131] This included remarks made by Douraid al-Assad, cousin of Bashar al-Assad, demanding the resignation of the Syrian Defence Minister, Fahd Jassem al-Freij, following the massacre by the Islamic State of hundreds of government troops captured after the IS victory at Tabqa Airbase.[132] This was shortly followed by Alawite protests in Homs demanding the resignation of the governor,[133] and the dismissal of Assad's cousin Hafez Makhlouf from his security position leading to his subsequent exile to Belarus.[134] Growing resentment towards Assad among Alawites was fuelled by the disproportionate number of soldiers killed in fighting hailing from Alawite areas,[135] a sense that the Assad regime has abandoned them,[136] as well as the failing economic situation.[137] Figures close to Assad began voicing concerns regarding the likelihood of its survival, with one saying in late 2014; "I don't see the current situation as sustainable ... I think Damascus will collapse at some point."[130]

In 2015, several members of the Assad family died in Latakia under unclear circumstances.[138] On 14 March, an influential cousin of Assad and founder of the shabiha, Mohammed Toufic al-Assad, was assassinated with five bullets to the head in a dispute over influence in Qardaha—the ancestral home of the Assad family.[139] In April 2015, Assad ordered the arrest of his cousin Munther al-Assad in Alzirah, Latakia.[140] It remains unclear whether the arrest was due to actual crimes.[141]

After a string of government defeats in northern and southern Syria, analysts noted growing government instability coupled with continued waning support for the Assad government among its core Alawite base of support,[142] and that there were increasing reports of Assad relatives, Alawites, and businessmen fleeing Damascus for Latakia and foreign countries.[143][144] Intelligence chief Ali Mamlouk was placed under house arrest sometime in April and stood accused of plotting with Assad's exiled uncle Rifaat al-Assad to replace Bashar as president.[145] Further high-profile deaths included the commanders of the Fourth Armoured Division, the Belli military airbase, the army's special forces and of the First Armoured Division, with an errant air strike during the Palmyra offensive killing two officers who were reportedly related to Assad.[146]

|

See also: Russian involvement in the Syrian Civil War and Foreign involvement in the Syrian civil war |

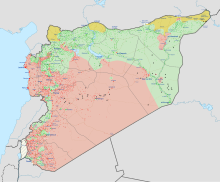

On 4 September 2015, when prospects of Assad's survival looked bleak, Russian President Vladimir Putin said that Russia was providing the Assad government with sufficiently "serious" help: with both logistical and military support.[147][148][149] Shortly after the start of direct military intervention by Russia on 30 September 2015 at the formal request of the Syrian government, Putin stated the military operation had been thoroughly prepared in advance and defined Russia's goal in Syria as "stabilising the legitimate power in Syria and creating the conditions for political compromise".[150] Putin's intervention saved the Assad regime at a time when it was on the verge of a looming collapse. It also enabled Moscow to achieve its key geo-strategic objectives such as total control of Syrian airspace, naval bases that granted permanent martial reach across the Eastern Mediterranean and easier access to intervene in Libya.[149]

In November 2015, Assad reiterated that a diplomatic process to bring the country's civil war to an end could not begin while it was occupied by "terrorists", although it was considered by BBC News to be unclear whether he meant only ISIL or Western-supported rebels as well.[151] On 22 November, Assad said that within two months of its air campaign Russia had achieved more in its fight against ISIL than the U.S.-led coalition had achieved in a year.[152] In an interview with Česká televize on 1 December, he said that the leaders who demanded his resignation were of no interest to him, as nobody takes them seriously because they are "shallow" and controlled by the U.S.[153][154] At the end of December 2015, senior U.S. officials privately admitted that Russia had achieved its central goal of stabilising Syria and, with the expenses relatively low, could sustain the operation at this level for years to come.[155]

In December 2015, Putin stated that Russia was supporting Assad's forces and was ready to back anti-Assad rebels in a joint fight against IS.[156]

On 22 January 2016, the Financial Times, citing anonymous "senior western intelligence officials", claimed that Russian general Igor Sergun, the director of GRU, the Main Intelligence Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, had shortly before his sudden death on 3 January 2016 been sent to Damascus with a message from Vladimir Putin asking that President Assad step aside.[157] The Financial Times' report was denied by Putin's spokesman.[158]

It was reported in December 2016 that Assad's forces had retaken half of rebel-held Aleppo, ending a 6-year stalemate in the city.[159][160] On 15 December, as it was reported government forces were on the brink of retaking all of Aleppo—a "turning point" in the civil war, Assad celebrated the "liberation" of the city, and stated, "History is being written by every Syrian citizen."[161]

After the election of Donald Trump, the priority of the U.S. concerning Assad was unlike the priority of the Obama administration, and in March 2017 U.S. Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley stated the U.S. was no longer focused on "getting Assad out",[162] but this position changed in the wake of the 2017 Khan Shaykhun chemical attack.[163] Following the missile strikes on a Syrian airbase on the orders of President Trump, Assad's spokesperson described the U.S.' behaviour as "unjust and arrogant aggression" and stated that the missile strikes "do not change the deep policies" of the Syrian government.[164] President Assad also told the Agence France-Presse that Syria's military had given up all its chemical weapons in 2013, and would not have used them if they still retained any, and stated that the chemical attack was a "100 percent fabrication" used to justify a U.S. airstrike.[165] In June 2017, Russian President Putin said "Assad didn't use the [chemical weapons]" and that the chemical attack was "done by people who wanted to blame him for that."[166] UN and international chemical weapons inspectors from the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) found the attack was the work of the Assad regime.[167]

On 7 November 2017, the Syrian government announced that it had signed the Paris Climate Agreement.[168] In May 2018, it recognized the independence of Russian-occupied separatist republics of Abhazia and South Ossetia in Georgia, leading to backlash from the European Union, United States, Canada and other countries.[169][170][171] On 30 August 2020, the First Hussein Arnous government was formed, which included a new Council of Ministers.[172]

In the 2021 presidential elections held on 26 May, Assad secured his fourth 7-year tenure; by winning 95.2% of the eligible votes. The elections were boycotted by the opposition and SDF; while the refugees and internally displaced citizens were disqualified to vote; enabling only 38% of Syrians to participate in the process. Independent international observers as well as representatives of Western countries described the elections as a farce. United Nations condemned the elections for directly violating Resolution 2254; and announced that it has "no mandate".[173][174][175][176][177]

On 10 August 2021, the Second Hussein Arnous government was formed.[178] Under Assad, Syria became a strong supporter of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine and was one of the five countries that opposed the UN General Assembly resolution denouncing the invasion, which called upon Russia to pull back its troops. Three days prior to the invasion, Foreign Minister Faisal Mekdad was dispatched to Moscow to affirm Syria's recognition of Donetsk and Luhansk separatist republics. A day after the invasion, Bashar al-Assad praised the invasion as "a correction of history and a restoration of balance in the global order after the fall of the Soviet Union" in a phone call with Vladimir Putin.[179][180][181] Syria became the first country after Russia to officially recognize the "independence and sovereignty" of the two breakaway regions in June 2022.[182][183][184]

On the 12th anniversary of beginning of the protests of Syrian Revolution, Bashar al-Assad held a meeting with Vladimir Putin during an official visit to Russia. In a televised broadcast with Putin, Assad defended Russia's "special military operation" as a war against "neo-Nazis and old Nazis" of Ukraine.[185][186] He recognised the Russian annexation of four Ukrainian oblasts and ratified the new Russian borders, claiming that the territories were "historically Russian". Assad also urged Russia to expand its military presence in Syria by establishing new bases and deploying more boots on the ground, making its military role permanent.[k]

In March 2023, he visited the United Arab Emirates and met with UAE's President Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan.[192] In May 2023, he attended the Arab League summit in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where he was welcomed by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.[193] In September 2023, Assad attended the Asian Games opening ceremony in Hangzhou and met with Chinese President Xi Jinping.[194] They announced the establishment of a China–Syria strategic partnership.[195]

|

Main article: Corruption in Syria |

|

See also: Economy of Syria |

At the onset of the Syrian revolution, corruption in Syria was endemic, and the country was ranked 129th in the 2011 Corruption Perceptions Index.[196] Since the 1970s, Syria's economy has been dominated by the patronage networks of Ba'ath party elites and Alawite loyalists of the Assad family, who established control over Syria's public sectors based on kinship and nepotism. The pervasive nature of corruption had been a source of controversy within the Ba'ath party circles and the wider public; as early as the 1980s.[197]

Bashar al-Assad's economic liberalization programme during the 2000s became a symbol of corruption and nepotism, as the beneficiaries of the scheme were Alawite loyalists who seized much of the privatized sectors and business assets. This alienated the government from the vast majority of the Syrian public, particularly rural Syrians and urban working classes, who widely loathed the ensuing economic disparities, which became overtly visible.[22][71] Assad's cousin Rami Makhlouf was the regime's most favored oligarch during this period, marked by the institutionalization of corruption, handicapping of small businesses and casting down private entrepreneurship.[198] The persistence of corruption, sectarian bias towards Alawites, nepotism and widespread bribery that existed in party, bureaucracy and military led to popular anger that resulted in the eruption of the 2011 Syrian Revolution. The protests were the most fierce in working-class neighbourhoods, which had long bore the brunt of the regime's exploitation policies that privileged its own loyalists.[199][200]

According to ABC News, as a result of the Syrian civil war, "government-controlled Syria is truncated in size, battered and impoverished."[201] Economic sanctions (the Syria Accountability Act) were applied long before the Syrian civil war by the U.S. and were joined by the EU at the outbreak of the civil war, causing disintegration of the Syrian economy.[202] These sanctions were reinforced in October 2014 by the EU and U.S.[203][204] Industry in parts of the country that are still held by the government is heavily state-controlled, with economic liberalisation being reversed during the current conflict.[205] The London School of Economics has stated that as a result of the Syrian civil war, a war economy has developed in Syria.[206] A 2014 European Council on Foreign Relations report also stated that a war economy has formed:

Three years into a conflict that is estimated to have killed at least 140,000 people from both sides, much of the Syrian economy lies in ruins. As the violence has expanded and sanctions have been imposed, assets and infrastructure have been destroyed, economic output has fallen, and investors have fled the country. Unemployment now exceeds 50 percent and half of the population lives below the poverty line ... against this backdrop, a war economy is emerging that is creating significant new economic networks and business activities that feed off the violence, chaos, and lawlessness gripping the country. This war economy – to which Western sanctions have inadvertently contributed – is creating incentives for some Syrians to prolong the conflict and making it harder to end it.[207]

A UN commissioned report by the Syrian Centre for Policy Research states that two-thirds of the Syrian population now lives in "extreme poverty".[208] Unemployment stands at 50 percent.[209] In October 2014, a $50 million mall opened in Tartus which provoked criticism from government supporters and was seen as part of an Assad government policy of attempting to project a sense of normalcy throughout the civil war.[210] A government policy to give preference to families of slain soldiers for government jobs was cancelled after it caused an uproar[135] while rising accusations of corruption caused protests.[137] In December 2014, the EU banned sales of jet fuel to the Assad government, forcing the government to buy more expensive uninsured jet fuel shipments in the future.[211]

Taking advantage of the increased role of the state as a result of the civil war, Bashar and his wife Asma have begun annexing Syria's economic assets from their loyalists, seeking to displace the old business elites and monopolize their direct control of the economy. Maher al-Assad, the brother of Bashar, has also become wealthy by overseeing the operations of Syria's state-sponsored captagon drug industry and seizing much of the spoils of war. The ruling couple currently owns vast swathes of Syria's shipping, real estate, telecommunications and banking sectors.[212][213] Significant changes have been happening to Syrian economy since the government's confiscation campaigns launched in 2019, which involved major economic assets being transferred to the Presidential couple to project their power and influence. Particularly noteworthy dynamic has been the rise of Asma al-Assad, who heads Syria's clandestine economic council and is thought to have become "a central funnel of economic power in Syria". Through her Syria Trust NGO, the backbone of her financial network, Asma vets the foreign aid coming to Syria; since the government authorizes UN organizations only if it works under state agencies.[214]

Corruption has been rising sporadically in recent years, with Syria being considered the most corrupt country in the Arab World.[215][216] As of 2022, Syria is the ranked second worst globally in the Corruption Perceptions Index.[217][218]

|

See also: Sectarianism and minorities in the Syrian civil war |

Hafiz al-Assad's government was widely counted amongst the most repressive Arab dictatorships of the 20th century. As Bashar inherited his father's mantle, he sought to implement "authoritarian upgrading" by purging the Old Guard and staffing party and military with loyalist Alawite officers, further entrenching the sectarianism within the system.[219][80] While officially the Ba'athist government adheres to a strict secularist doctrine, in practice it has implemented sectarian engineering policies in the society to suppress dissent and monopolize its absolute power.[220]

"During Hafez-al-Assad's reign, he resorted to emphasising the sectarian identities that the previous Ba'ath Party rejected; believing the only way to ensure stability was through building a trusted security force... Hafez pursued a strategy to “make the Alawite community a loyal monolith while keeping Syria's Sunni majority divided”. Yet Syria became a police state, enforcing stability through threat of brute force repression... Bashar had already followed in his father's footsteps, carefully manoeuvring his most loyal allies into the military-security apparatus, government ministries and the Ba’ath party."

— Antonia Robson[221]

The regime has attempted to portray itself to the outside world as "the protector of minorities" and instills the fear of the majority rule in the society to mobilize loyalists from minorities.[222] Assad loyalist figures like Michel Samaha have advocated sectarian mobilization to defend the regime from what he labelled as the “sea of Sunnis.” Assad regime has unleashed sectarian violence through private Alawite militias like the Shabiha, particularly in Sunni areas. Alawite religious iconography and communal sentiments are common themes used by Alawite warrior-shaykhs who lead the Alawite militias; as justification to commit massacres, abductions and torture in opposition strongholds.[223] Various development policies adopted by the regime had followed a sectarian pattern. An urbanization scheme implemented by the government in the city of Homs led to expulsions of thousands of Sunni residents during the 2000s, while Alawite majority areas were left intact.[224]

Even as Syrian Ba'athism absorbed diverse communal identities into the homogenous unifying discourse of the state; socio-political power became monopolized by Alawite loyalists. Despite officially adhering to non-confessionalism, Syrian Armed Forces have also been institutionally sectarianized. While the conscripts and lower-ranks are overwhelmingly non-Alawite, the higher ranks are packed by Alawite loyalists who effectively control the logistics and security policy. Elite units of the Syrian military such as the Tiger Forces, Republican Guard, 4th Armoured Division, etc. regarded by the government as crucial for its survival; are composed mostly of Alawites. Sunni officers are under constant surveillance by the secret police, with most of them being assigned with Alawite assistants who monitor their movements. Pro-regime paramilitary groups such as the National Defense Force are also organized around sectarian loyalty to the Ba'athist government. During the Syrian Revolution uprisings, the Ba'athist government deployed a securitization strategy that depended on sectarian mobilization, unleashing violence on protestors and extensive crackdowns across the country, prompting opposition groups to turn to armed revolt. Syrian society was further sectarianized following the Iranian intervention in the Syrian civil war, which witnessed numerous Khomeinist militant groups sponsored by Iran fight in the side of the Assad government.[225][221]

|

See also: Human rights in Syria |

Ba'athist government has been ruling Syria as a totalitarian state, policing every aspect of Syrian society for decades. Commanders of government's security forces – consisting of Syrian Arab Army, secret police, Ba'athist paramilitaries – directly implement the executive functions of the state, with scant regard for legal processes and bureaucracy. The surveillance system of the Mukhabarat is pervasive, with the total number of agents working for its various branches estimated to be as high as 1:158 ratio with the civilian population. Security services shut down civil society organizations, curtail freedom of movement within the country and bans non-Ba'athist political literature and symbols.[99][226] In 2010, Human Rights Watch published the report "A Wasted Decade" documenting repression during Assad's first decade of emergency rule; marked by arbitrary arrests, censorship and discrimination against Syrian Kurds.[226][227]

Throughout the 2000s, the dreaded Mukhabarat agents carried out routine abductions, arbitrary detentions and torture of civilians. Numerous show trials were conducted against dissidents, filling Syrian prisons with journalists and human rights activists. Members of Syria's General Intelligence Directorate had long enjoyed broad privileges to carry out extrajudicial actions and they have immunity from criminal offences. In 2008, Assad extended this immunity to other departments of security forces.[227] Human Rights groups, such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, have detailed how the Assad government's secret police tortured, imprisoned, and killed political opponents, and those who speak out against the government.[228][229] In addition, some 600 Lebanese political prisoners are thought to be held in government prisons since the Syrian occupation of Lebanon, with some held for as long as over 30 years.[230] Since 2006, the Assad government has expanded the use of travel bans against political dissidents.[231] In an interview with ABC News in 2007, Assad stated: "We don't have such [things as] political prisoners," though The New York Times reported the arrest of 30 Syrian political dissidents who were organising a joint opposition front in December 2007, with 3 members of this group considered to be opposition leaders being remanded in custody.[232]

The government also denied permission for human rights organizations and independent NGOs to work in the country.[227] In 2010, Syria banned face veils at universities.[233][234] Following the protests of Syrian Revolution in 2011, Assad partially relaxed the veil ban.[235]

Foreign Affairs journal released an editorial on the Syrian situation in the wake of the 2011 protests:[236]

During its decades of rule... the Assad family developed a strong political safety net by firmly integrating the military into the government. In 1970, Hafez al-Assad, Bashar's father, seized power after rising through the ranks of the Syrian armed forces, during which time he established a network of loyal Alawites by installing them in key posts. In fact, the military, ruling elite, and ruthless secret police are so intertwined that it is now impossible to separate the Assad regime from the security establishment. Bashar al-Assad's threat to use force against protesters would be more plausible than Tunisia's or Egypt's were. So, unlike in Tunisia and Egypt, where a professionally trained military tended to play an independent role, the regime and its loyal forces have been able to deter all but the most resolute and fearless oppositional activists... At the same time, it is significantly different from Libya, where the military, although brutal and loyal to the regime, is a more disorganized group of militant thugs than a trained and disciplined army.

Between 2011 and 2013; the state security apparatus is believed to have tortured and killed over 10,000 civil activists, political dissidents, journalists, civil defense volunteers and those accused of treason and terror charges, as part of a campaign of deadly crackdown ordered by Assad.[237] In June 2023, UN General Assembly voted in favour of establishing an independent body to investigate the whereabouts of hundreds of thousands of missing civilians who have been forcibly disappeared, killed or languishing in Assad regime's dungeons and torture chambers. The vote was condemned by Russia, North Korea and Iran.[238][239][240]

In 2023, Canada and Netherlands filed a lawsuit against Syria at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), charging the latter with violating the United Nations Convention Against Torture. The joint petition accused the Syrian regime of organizing "unimaginable physical and mental pain and suffering" as a strategy to collectively punish the Syrian population.[241][242][243] Russia vetoed UN Security Council efforts to prosecute Bashar al-Assad at the International Criminal Court.[244]

|

Further information: Arab Belt Project, Arabization in Syria, and Qamishli massacre |

Ba'athist Syria had long banned Kurdish language in schools and public institutions; and discrimination against Kurds steadily increased during the rule of Bashar al-Assad. State policy officially suppressed Kurdish culture; with more than 300,000 Syrian Kurds being rendered stateless. Kurdish grievances against state persecution eventually culminated in the 2004 Qamishli Uprisings, which were crushed down violently after sending Syrian military forces. The ensuing crackdown resulted in the killings of more than 36 Kurds and injuring at least 160 demonstrators. More than 2000 civilians were arrested and tortured in government detention centres. Restrictions on Kurdish activities has been further tightened following the Qamishli massacre, with the Assad regime virtually banning all Kurdish cultural gatherings and political activism under the charges of “inciting strife” or “weakening national sentiment.” During 2005–2010, Human Rights Watch verified security crackdowns on at least 14 Kurdish political and cultural gatherings.[227][226] In March 2008, Syrian military opened fire at a Kurdish gathering in Qamishli that marked Nowruz, killing three and injuring five civilians.[245]

|

Main articles: Censorship in Syria and Internet censorship in Syria |

On 22 September 2001, Assad decreed a Press Law that tightened government control over all literature printed or published in Syria; ranging from newspapers to books, pamphlets and periodicals. Publishers, writers, editors, distributors, journalists and other individuals accused of violating the Press Law are imprisoned or fined. Censorship has also been expanded into the cyberspace, and various websites are banned. Numerous bloggers and content creators have been arrested under various "national security" charges.[227]

A 2007 law requires internet cafés to record all the comments users post on chat forums.[246] Another decree in 2008 obligated internet cafes to keep records of their customers and notify them routinely to the police.[247] Websites such as Arabic Wikipedia, YouTube, and Facebook were blocked intermittently between 2008 and February 2011.[248][249][250] Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) ranked Syria as the third dangerous country to be an online blogger in 2009. Individuals are arrested based on a wide variety of accusations; ranging from undermining "national unity" to posting or sharing "false" content.[227][247]

Syria was ranked as the third most censored country in CPJ's 2012 report. Apart from restrictions for international journalists that prohibit their entry, domestic press is controlled by state agencies that promote Ba'athist ideology. From 2011, the Syrian government has issued a complete media blackout and foreign correspondents were quickly detained, abducted or tortured. As a result, the outside world is able to know of situations happening inside Syria only through videos of independent civilian journalists. The Assad government has shut down internet coverage, mobile networks as well as telephone lines in areas under its control to prevent any news that has its attempts to monopolize information related to Syria.[251]

|

Further information: Casualties of the Syrian civil war and Syrian refugee crisis |

The crackdown ordered by Bashar al-Assad against Syrian protestors was the most ruthless of all military clampdowns in the entire Arab Spring. As violence deteriorated and death toll mounted to the thousands; the European Union, Arab League and United States began imposing wide range of sanctions against Assad regime. By December 2011, United Nations had declared the situation in Syria to be a "civil war".[252] By this point, all the protestors and armed resistance groups had viewed the unconditional resignation of Bashar al-Assad as part of their core demands. In July 2012, Arab League held an emergency session demanding the "swift resignation" of Assad and promised "safe exit" if he accepted the offer.[253][254] Assad rebuffed the offers, instead seeking foreign military support from Iran and Russia to defend his embattled regime through scorched-earth tactics, massacres, sieges, forced starvations, ethnic cleansing, etc.[255]

The crackdowns and extermination campaigns of Assad regime resulted in the Syrian refugee crisis; causing the forced displacement of 14 million Syrians, with around 7.2 million refugees.[256] This has made the Syrian refugee crisis the largest refugee crisis in the world; and UNHCR High Commissioner Filippo Grandi has described it as "the biggest humanitarian and refugee crisis of our time and a continuing cause for suffering."[256][257]

Eva Koulouriotis has described Bashar al-Assad as the "master of ethnic cleansing in the 21st century".[258] During the course of the civil war, Assad ordered depopulation campaigns throughout the country to re-shape its demography in favour of his regime, and the military tactics have been compared to the persecutions of the Bosnian war. Between 2011 and 2015, Ba'athist militias are reported to have committed 49 ethno-sectarian massacres for the purpose of implementing its social engineering agenda in the country. Alawite loyalist militias known as the Shabiha have been launched into Sunni villages and towns; perpetrating numerous anti-Sunni massacres. These include the Houla, Bayda and Baniyas massacres, Al-Qubeir massacre, Al-Hasawiya massacre, etc. which have resulted in hundreds of deaths; with hundreds of thousands of residents fleeing under threats of regime persecution and sexual violence. Pogroms and deportations were pronounced in central Syrian regions and Alawite majority coastal areas, where the Syrian military and Hezbollah view as a priority to establish strategic control by expelling Sunni residents and bringing in Iran-backed Shia militants.[259][260][258][261] In 2016, UN officials criticized Bashar al-Assad for pursuing demographic engineering and ethnic cleansing in Darayya district in Damascus, under the guise of de-escalation deals.[262]

Syrian government forces have pursued mass-killings of civilian populations as part of its war-strategy throughout the conflict; and is responsible for inflicting more than 90% of the total civilian deaths in the Syrian civil war.[7] Between 2011 and 2021, a minimum of 306,000 civilian deaths are estimated to have occurred by the UN.[105][106] As of 2022, total death toll has risen to approximately 580,000.[263] An additional 154,000 civilians have been forcibly disappeared or subject to arbitrary detentions across Syria, between 2011 and 2023. As of 2023, more than 135,000 individuals are being tortured, incarcerated or dead in Ba'athist prison networks, including thousands of women and children.[264]

|

Further information: Human rights violations during the Syrian civil war and Use of chemical weapons in the Syrian civil war |

"The nature and extent of Assad's violence is strategic in design and effect. He is pursuing a strategy of terror, siege, and depopulation in key areas, calculating that winning back the loyalty of much of the Sunni middle class and underclass is highly unlikely and certainly not worth the resources and political capital. Better to level half the country than to give it over to the opposition."

— Emile Hokayem, Senior Fellow at International Institute for Strategic Studies[265]

Numerous politicians, dissidents, authors and journalists have nicknamed Assad as the "butcher" of Syria for his war-crimes, anti-Sunni sectarian mass-killings, chemical weapons attacks and ethnic cleansing campaigns.[266][267][268][269] The Federal Bureau of Investigation has stated that at least 10 European citizens were tortured by the Assad government while detained during the Syrian civil war, potentially leaving Assad open to prosecution by individual European countries for war crimes.[270][167] UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay stated in December 2013 that UN investigations directly implicated Bashar al-Assad guilty of crimes against humanity and pursuing an extermination strategy developed "at the highest level of government, including the head of state."[271]

Stephen Rapp, the U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes Issues, stated in 2014 that the crimes committed by Assad are the worst seen since those of Nazi Germany.[272] In March 2015, Rapp further stated that the case against Assad is "much better" than those against Slobodan Milošević of Serbia or Charles Taylor of Liberia, both of whom were indicted by international tribunals.[273] Charles Lister, Director of the Countering Terror and Extremism Program at Middle East Institute, describes Bashar al-Assad as "21st century's biggest war criminal".[177]

In a February 2015 interview with the BBC, Assad dismissed accusations that the Syrian Arab Air Force used barrel bombs as "childish", claiming that his forces have never used these types of "barrel" bombs and responded with a joke about not using "cooking pots" either.[274] The BBC Middle East editor conducting the interview, Jeremy Bowen, later described Assad's statement regarding barrel bombs as "patently not true".[275][276] As soon as demonstrations arose in 2011–2012, Bashar al-Assad opted to implement the "Samson option", the characteristic approach of the neo-Ba'athist regime since the era of Hafiz al-Assad; wherein protests were violently suppressed and demonstrators were shot and fired at directly by the armed forces. However, unlike Hafiz; Bashar had even less loyalty and was politically fragile, exacerbated by alienation of the majority of the population. As a result, Bashar chose to crack down on dissent far more comprehensively and harshly than his father; and a mere allegation of collaboration was reason enough to get assassinated.[277]

Nadim Shehadi, the director of The Fares Center for Eastern Mediterranean Studies, stated that "In the early 1990s, Saddam Hussein was massacring his people and we were worried about the weapons inspectors," and claimed that "Assad did that too. He kept us busy with chemical weapons when he massacred his people."[278][279] Contrasting the policies of Hafiz al-Assad and that of his son Bashar, former Syrian vice-president and Ba'athist dissident Abdul Halim Khaddam states:

"The Father had a mind and the Son has a loss of reason. How could the army use its force and the security appartus with all its might to destroy Syria because of a protest against the mistakes of one of your security officials. The father would act differently. Father Hafiz hit Hama after he encircled it, warned and then hit Hama after a long siege... But his son is different. On the subject of Daraa, Bashar gave instructions to open fire on the demonstrators."[280]

Human rights organizations and criminal investigators have documented Assad's war crimes and sent it to the International Criminal Court for indictment.[281] Since Syria is not a party to the Rome Statute, International Criminal Court requires authorization from the UN Security Council to send Bashar al-Assad to tribunal. As this gets consistently vetoed by Assad's primary backer Russia, ICC prosecutions have not transpired. On the other hand, courts in various European countries have begun prosecuting and convicting senior Ba'ath party members, Syrian military commanders and Mukhabarat officials charged with war crimes.[282] In September 2015, France began an inquiry into Assad for crimes against humanity, with French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius stating "Faced with these crimes that offend the human conscience, this bureaucracy of horror, faced with this denial of the values of humanity, it is our responsibility to act against the impunity of the killers".[283]

In February 2016, head of the UN Commission of Inquiry on Syria, Paulo Pinheiro, told reporters: "The mass scale of deaths of detainees suggests that the government of Syria is responsible for acts that amount to extermination as a crime against humanity." The UN Commission reported finding "unimaginable abuses", including women and children as young as seven perishing while being held by Syrian authorities. The report also stated: "There are reasonable grounds to believe that high-ranking officers—including the heads of branches and directorates—commanding these detention facilities, those in charge of the military police, as well as their civilian superiors, knew of the vast number of deaths occurring in detention facilities ... yet did not take action to prevent abuse, investigate allegations or prosecute those responsible".[284]

In March 2016, the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs led by New Jersey Rep. Chris Smith called on the Obama administration to create a war crimes tribunal to investigate and prosecute violations "whether committed by the officials of the Government of Syria or other parties to the civil war".[285]

In June 2018, Germany's chief prosecutor issued an international arrest warrant for one of Assad's most senior military officials, Jamil Hassan.[286] Hassan is the head of Syria's powerful Air Force Intelligence Directorate. Detention centers run by Air Force Intelligence are among the most notorious in Syria, and thousands are believed to have died because of torture or neglect. Charges filed against Hassan claim he had command responsibility over the facilities and therefore knew of the abuse. The move against Hassan marked an important milestone of prosecutors trying to bring senior members of Assad's inner circle to trial for war crimes.

In an investigative report about the Tadamon Massacre, Professors Uğur Ümit Üngör and Annsar Shahhoud, found witnesses who attested that Assad gave orders for the Syrian Military Intelligence to direct the Shabiha to kill civilians.[287]

On 15 November 2023, France issued an arrest warrant against Syrian President Bashar Assad over the use of banned chemical weapons against civilians in Syria.[14] In May 2024, French anti-terrorism prosecutors requested the Paris appeals court to consider revoking Assad's arrest warrant, asserting his absolute immunity as a serving head of state.[288]

On 26 June 2024, the Paris appeals court determined that the international arrest warrant issued by France against Assad for alleged complicity in war crimes during the Syrian civil war remains valid. This decision was confirmed by attorneys involved in the case.[288]

According to the lawyers, this ruling marked the first instance where a national court acknowledged that the personal immunity of a serving head of state is not absolute, as reported by The Associated Press.[288]

|

Main article: Use of chemical weapons in the Syrian civil war |

|

See also: Syria and weapons of mass destruction |

The Syrian military has deployed chemical warfare as a systematic military strategy in the Syrian civil war, and is estimated to have committed over 300 chemical attacks, targeting civilian populations throughout the course of the conflict.[289][290] Investigation conducted by the GPPi research institute documented 336 confirmed attacks involving chemical weapons in Syria between 23 December 2012 and 18 January 2019. The study attributed 98% of the total verified chemical attacks to the Assad's regime. Almost 90% of the attacks had occurred after the Ghouta chemical attack in August 2013.[291][292]

Syria joined the Chemical Weapons Convention and OPCW member state in October 2013, and there are currently three OPCW missions with UN mandates to investigate chemical weapons issues in Syria. These are the Declaration Assessment Team (DAT) to verify Syrian declarations of CW Programme; OPCW Fact-Finding Mission (FFM) tasked to identify the chemical attacks and type of weapons used; and the Investigation and Identification Team (IIT) which investigates the perpetrators of the chemical attacks. The conclusions are submitted to the United Nations bodies.[293]

In April 2021, Syria was suspended from OPCW through the public vote of member states, for not co-operating with the body's Investigation Identification Team (IIT) and violating the Chemical Weapons Convention.[294][295][296] Findings of another investigation report published the OPCW-IIT in July 2021 concluded that the Syrian regime had engaged in confirmed chemical attacks at least 17 times, out of the reported 77 chemical weapon attacks attributed to Assadist forces.[297][298] As of March 2023, independent United Nations inquiry commissions have confirmed at least nine chemical attacks committed by forces loyal to the Assad government.[299][300]

The deadliest chemical attack have been the Ghouta chemical attacks, when Assad government forces launched the nerve agent sarin into civilian areas during its brutal Siege of Eastern Ghouta in early hours of 21 August 2013. Thousands of infected and dying victims flooded the nearby hospitals, showing symptoms such as foaming, body convulsions and other neurotoxic symptoms. An estimated 1,100-1,500 civilians; including women and children, are estimated to have been killed in the attacks.[301][302][303] The attack was internationally condemned and represented the deadliest use of chemical weapons since the Iran-Iraq war.[304][305] On 21 August 2022, United States government marked the ninth anniversary of Ghouta Chemical attacks stating: "United States remembers and honors the victims and survivors of the Ghouta attack and the many other chemical attacks we assess the Assad regime has launched. We condemn in the strongest possible terms any use of chemical weapons anywhere, by anyone, under any circumstances... The United States calls on the Assad regime to fully declare and destroy its chemical weapons program... and for the regime to allow the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons’ Declaration Assessment Team."[306]

In April 2017, there was a sarin chemical attack on Khan Sheikhoun that killed more than 80 people.[307][308][237] The attack prompted U.S. President Donald Trump to order the U.S. military to launch 59 missiles at the Syrian Shayrat airbase.[309][310] Several months later, a joint report from the UN and international chemical weapons inspectors concluded that the attack was the work of the Assad regime.[167][311]

In April 2018, a chemical attack occurred in Douma, prompting the U.S. and its allies to accuse Assad of violating international laws and initiated joint missile strikes at chemical weapons facilities in Damascus and Homs. Both Syria and Russia denied the involvement of the Syrian government at this time.[312][313] The third report published on 27 January 2023 by the OPCW-IIT concluded that the Assad regime was responsible for the 2018 Douma chemical attack which killed at least 43 civilians.[l]

|

See also: Holocaust denial |

In a speech delivered at the Ba'ath party's central committee meeting in December 2023, Bashar al-Assad claimed that there was "no evidence" of the killings of six million Jews during the Holocaust. Emphasizing that Jews were not the sole victims of Nazi extermination campaigns, Assad alleged that the Holocaust was "politicized" by Allied powers to facilitate the mass-deportation of European Jews to Palestine, and that it was used as an excuse to justify the creation of Israel. Assad also accused the U.S. government of financially and militarily sponsoring the rise of Nazism during the inter-war period.[314][315]

|

Further information: Syrian opposition |

The secular resistance to Assad rule is mainly represented by the Syrian National Council and National Coalition of Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces, two political bodies that constitute a coalition of centre-left and right-wing conservative factions of the Syrian opposition. Military commanders and civilian leaders of Free Syrian Army militias are represented in these councils. The coalition represents the political wing of the Syrian Interim Government and seeks the democratic transition of Syria through grass-roots activism, protests and armed resistance to overthrow the Ba'athist dictatorship.[316][317][318] A less influential faction within the Syrian opposition is the National Coordination Committee for Democratic Change (NCC), a coalition of left-wing socialist parties that seek to end the rule of Assad family but without foreign involvement. Established in June 2011, major parties in the NCC coalition are the Democratic Arab Socialist Union, Syrian Democratic People's Party and the Communist Labour Party.[319]

National Democratic Rally (NDR) was an older left-wing opposition coalition of socialist parties formed in 1980, but banned by the Baathist government. NDR was active during the nation-wide protests of the 1980s and the Damascus Spring of the 2000s.[320] During the early years of the civil war, the Druze in Syria primarily sought to remain neutral, "seeking to stay out of the conflict". Druze-Israeli politician Majalli Wahabi claimed in 2016 that over half support the Assad government despite its relative weakness in Druze areas.[321] The "Sheikhs of Dignity" movement, which had sought to remain neutral and to defend Druze areas,[322] blamed the government after its leader Sheikh Wahid al-Balous was assassinated and organized large scale protests which left six government security personnel dead.[323] Druze community became fervently opposed to the Assad government over time and has been vocal about its opposition to increasing Iranian interference in Syria.[324] In August 2023, mass protests against Assad regime erupted in the Druze-majority city of Suweida,[325][326] which eventually spread to other regions of Southern Syria.[327][328][329] Druze cleric Hikmat al-Hajiri, religious leader of Syrian Druze community, has declared war against "Iranian invasion of the country".[330] Syrian Sufi scholar Muhammad al-Yaqoubi, a fervent opponent of both the Ba'athist regime and Islamic State group, has described Assad's rule as a "reign of terror" that wreaked havoc and enormous misery on the Syrian populace.[331]

Central to the regime's support base is the Ba'athist loyalists who dominate Syrian politics, trade unions, youth organizations, students unions, bureaucracy and armed forces.[332] Ba'ath party institutions and its political activities form the "vital pillars of regime survival". Family networks of politicians in the Ba'ath party-led National Progressive Front (NPF) and businessmen loyal to the Assad family form another pole of support. Electoral listing is supervised by Ba'ath party leadership which expels candidates not deemed "sufficiently loyal".[333][334][335] Although it has been reported at various stages of the Syrian civil war that religious minorities such as the Alawites and Christians in Syria favour the Assad government because of its secularism,[336][337] opposition exists among Assyrian Christians who have claimed that the Assad government seeks to use them as "puppets" and deny their distinct ethnicity, which is non-Arab.[338] Although Syria's Alawite community forms Bashar al-Assad's core support base and dominate the military and security apparatus,[339][340] in April 2016, BBC News reported that Alawite leaders released a document seeking to distance themselves from Assad.[341]

Kurdish Supreme Committee was a coalition of 13 Kurdish political parties opposed to Assad regime. Before its dissolution in 2015, the committee consisted of KNC and PYD.[319] Circassians in Syria have also become strong opponents of the regime as Ba'athist crackdowns and massacres across Syria intensified viciously; and members of Circassian ethnic minority have attempted to escape Syria, fearing persecution.[342] In 2014, the Christian Syriac Military Council, the largest Christian organization in Syria, allied with the Free Syrian Army opposed to Assad,[343] joining other Syrian Christian militias such as the Sutoro who had joined the Syrian opposition against the Assad government.[344] Abu Muhammad al-Joulani, commander of the Tahrir al-Sham rebel militia, condemned Assad regime for converting Syria "into an ongoing earthquake the past 12 years", in the context of the 2023 Turkey-Syria earthquakes.[345]

"In June 2014, Assad won a disputed presidential election held in government-controlled areas (and boycotted in opposition-held areas[346] and Kurdish areas governed by the Democratic Union Party[347]) with 88.7% of the vote. Turnout was estimated to be 73.42% of eligible voters, including those in rebel-controlled areas.[348] The regime's electoral commission also disqualified millions of Syrian citizens displaced outside the country from voting.[349] Independent observers and academic scholarship unanimously describe the event as a sham election organized to legitimise Assad's rule.[350][351][352] In his inauguration ceremony, Bashar denounced the opposition as "terrorists" and "traitors"; while attacking the West for backing what he described as the "fake Arab spring".[353]

Times of Israel reported that although various individuals interviewed in a "Sunni-dominated, middle-class neighborhood of central Damascus" exhibited fealty for Assad; it was not possible to discern the actual support for the regime due to the ubiquitous influence of the secret police in the society.[354] Ba'athist dissident Abdul Halim Khaddam who had served as Syrian Vice President during the tenures of both Hafiz and Bashar, disparaged Bashar al-Assad as a pawn in Iran's imperial scheme. Contrasting the power dynamics that existed under both the autocrats, Khaddam stated:

"[Bashar] is not like his father.. He never allowed the Iranians to intervene in Syrian affairs.. During Hafez Assad's time, an Iranian delegation arrived in Syria and attempted to convert some of the Muslim Alawite Syrians to Shia Islam... Assad ordered his minister of foreign Affairs to summon the Iranian ambassador to deliver an ultimatum: The delegation has 24 hours to exit Syria.... They had no power [during Hafez's rule], unlike Bashar who gave them [Iranians] power and control."[355][356]

Foreign journalists and political observers who travelled to Syria have described it as the most "ruthless police state" in the Arab World. Assad's violent repression of Damascus Spring of the early 2000s and the publication of a UN report that implicated him in the assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, exacerbated Syria's post-Cold War isolation.[357][358] Following global outrage against Assad regime's deadly crackdown on the Arab Spring protestors which led to the Syrian civil war, scorched-earth policy against the civilian populations resulting in more than half a million deaths, mass murders and systematic deployment of chemical warfare throughout the conflict; Bashar al-Assad became an international pariah and numerous world leaders have urged him to resign.[359][358][360][361]

Since 2011, Bashar al-Assad has lost recognition from several international organizations such as the Arab League (in 2011),[362] Union for the Mediterranean (in 2011)[363] and Organization of Islamic Co-operation (in 2012).[364][365] United States, European Union, Turkey, Arab League and various countries began enforcing broad sets of sanctions against Syrian regime from 2011, with the objective of forcing Assad to resign and assist in a political solution to the crisis.[366] International bodies have criticized one-sided elections organized by Assad government during the conflict. In the 2014 London conference of countries of the Friends of Syria group, British Foreign Secretary William Hague characterized Syrian elections as a "parody of democracy" and denounced the regime's "utter disregard for human life" for perpetrating war-crimes and state-terror on the Syrian population.[367] Assad's policy of holding elections under the circumstances of an ongoing civil war were also rebuked by the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon.[368]

Georgia suspended all relations with Syria following Bashar al-Assad's recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, condemning his government as a "Russian manipulated regime" that supported Russian occupation and "ethnic cleansing".[m] Following Assad's strong backing of Russian invasion of Ukraine and recognition of the breakaway separatist republics, Ukraine cut off all diplomatic relations with Syria in June 2022. Describing Assad's policies as "worthless", Ukrainian President Volodimir Zelensky pledged to expand further sanctions against Syria.[372][373] In March 2023, National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine put into effect a range of sanctions targeting 141 firms and 300 individuals linked to Assad regime, Russian weapons manufacturers and Iranian dronemakers. This was days after Assad's visit to Moscow, wherein he justified Russian invasion of Ukraine as a fight against "old and new Nazis". Bashar al-Assad, Prime Minister Hussein Arnous and Foreign Minister Faisal Mikdad were amongst the individuals who were sanctioned.[n] Sanctions also involved freezing of all Syrian state properties in Ukraine, curtailment of monetary transactions, termination of economic commitments and recision of all official Ukrainian awards.[377] Syria formally broke its diplomatic ties to Ukraine on July 20, citing the principle of reciprocity.[379]

In April 2023, a French court declared three high-ranking Ba'athist security officials guilty of crimes against humanity, torture and various war-crimes against French-Syrian citizens. These included Ali Mamlouk, director of National Security Bureau of Syrian Ba'ath party and Jamil Hassan, former head of the Syrian Air Force Intelligence Directorate.[380][381] France had issued international arrest warrants against the three officers over the case in 2018.[382] In May 2023, French Foreign Minister Catherine Colonna publicly demanded the prosecution of Bashar al-Assad for engaging in chemical warfare and killing hundreds of thousands of people; branding him as "the enemy of his own people".[383][384] On 15 November 2023, France issued an arrest warrant against Assad for use of chemical weapons against civilians in Syria.[14]

Bashar al-Assad is widely criticised by left-wing activists and intellectuals world-wide for appropriating leftist ideologies and its socialist, progressive slogans as a cover for his own family rule and to empower a loyalist clique of elites at the expense of ordinary Syrians. His close alliance with clergy-ruled Khomeinist Iran and its sectarian militant networks; while simultaneously pursuing a policy of locking up left-wing critics of Assad family has been subject to heavy criticism.[385]

Egyptian branch of the Iraqi Ba'ath movement has declared its strong support to the Syrian revolution; denouncing Ba'athist Syria as a repressive dictatorship controlled by the "Assad gang". It has attacked Assad family's Ba'athist credentials, accusing the Syrian Ba'ath party of acting as the borderguards of Israel ever since its overthrowal of the Ba'athist National Command during the 1966 coup d'état. Describing Bashar al-Assad as a disgraceful person for inviting hostile powers like Iran to Syria, Egyptian Ba'athists have urged the Syrian revolutionaries to unite in their efforts to overthrow the Assad regime and resist foreign imperialism.[386]

Describing Assad's regime as a mafia state that thrives on corruption and sectarianism, Lebanese socialist academic Gilbert Achcar stated: