Inland Northern (American) English,[1] also known in American linguistics as the Inland North or Great Lakes dialect,[2] is an American English dialect spoken primarily by White Americans in a geographic band reaching from the major urban areas of Upstate New York westward along the Erie Canal and through much of the U.S. Great Lakes region. The most distinctive Inland Northern accents are spoken in Chicago, Milwaukee, Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo, Rochester, and Syracuse.[3] The dialect can be heard as far west as eastern Iowa and even among certain demographics in the Twin Cities, Minnesota.[4] Some of its features have also infiltrated a geographic corridor from Chicago southwest along historic Route 66 into St. Louis, Missouri; today, the corridor shows a mixture of both Inland North and Midland American accents.[5] Linguists often characterize the western Great Lakes region's dialect separately as North-Central American English.

The early 20th-century accent of the Inland North was the basis for the term "General American",[6][7] though the regional accent has since altered, due to the Northern Cities Vowel Shift: its now-defining chain shift of vowels that began in the 1930s or possibly earlier.[8] A 1969 study first formally showed lower-middle-class women leading the regional population in the first two stages (raising of the TRAP vowel and fronting of the LOT/PALM vowel) of this shift, documented since the 1970s as comprising five distinct stages.[6] However, evidence since the mid-2010s suggests a retreat away from the Northern Cities Shift in many Inland Northern cities and toward a less marked American accent.[9][10][11] Various common names for the Inland Northern accent exist, often based on city, for example: Chicago accent, Detroit accent, Milwaukee accent, etc.

Geographic distribution

[edit]

The dialect region called the "Inland North" consists of western and central New York State (Utica, Ithaca, Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, Binghamton, Jamestown, Fredonia, Olean); northern Ohio (Akron, Cleveland, Toledo), Michigan's Lower Peninsula (Detroit, Flint, Grand Rapids, Lansing); northern Indiana (Gary, South Bend); northern Illinois (Chicago, Rockford); southeastern Wisconsin (Kenosha, Racine, Milwaukee); and, largely, northeastern Pennsylvania's Wyoming Valley/Coal Region (Scranton and Wilkes-Barre). This is the dialect spoken in part of America's chief industrial region, an area sometimes known as the Rust Belt. Northern Iowa and southern Minnesota may also variably fall within the Inland North dialect region; in the Twin Cities, educated middle-aged men in particular have been documented as aligning to the accent, though this is not necessarily the case among other demographics of that urban area.[4]

Linguists identify the "St. Louis Corridor", extending from Chicago down into St. Louis, as a dialectally remarkable area, because young and old speakers alike have a Midland accent, except for a single middle generation born between the 1920s and 1940s, who have an Inland Northern accent diffused into the area from Chicago.[12]

Erie, Pennsylvania, though in the geographic area of the "Inland North" and featuring some speakers of this dialect, never underwent the Northern Cities Shift and often shares more features with Western Pennsylvania English due to contact with Pittsburghers, particularly with Erie as their choice of city for summer vacations.[13] Many African Americans in Detroit and other Northern cities are multidialectal and also or exclusively use African-American Vernacular English rather than Inland Northern English, but some do use the Inland Northern dialect.

Social factors

[edit]The dialect's progression across the Midwest has stopped at a general boundary line traveling through central Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois and then western Wisconsin, on the other sides of which speakers have continued to maintain their Midland and North Central accents. Sociolinguist William Labov theorizes that this separation reflects a political divide and a controlled study of his shows that Inland Northern speakers tend to be more associated with liberal politics than those of the other dialects, especially as Americans continue to self-segregate in residence based on ideological concerns.[14] Former President Barack Obama, for example, has a mild Inland Northern accent despite not having lived in the dialect region until early adulthood.[14]

Phonology and phonetics

[edit]

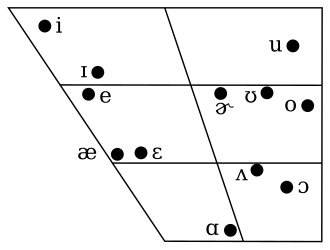

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tense | lax | lax | tense | |||

| Close | i | ɪ | ʊ | u | ||

| Close-mid | eɪ | ə | oʊ | |||

| Open-mid | æ | ɛ | ʌ | |||

| Open | ɑ | ɔ | ||||

| Diphthongs | aɪ ɔɪ aʊ | |||||

| Pure vowels (Monophthongs) | ||

|---|---|---|

| English diaphoneme | Inland Northern realization | Example words |

| /æ/ | æə~eə~ɪə | bath, trap, man |

| /ɑː/ | a~ä | blah, father, spa |

| /ɒ/† | lot, bother, wasp | |

| /ɔː/ | ɒ~ɑ | dog, loss, off |

| all, bought, saw | ||

| /ɛ/ | ɛ~ɜ~ɐ | dress, met, bread |

| /ə/ | ə | about, syrup, arena |

| /ɪ/ | ɪ~ɪ̈ | hit, skim, tip |

| /iː/ | ɪi~i | beam, chic, fleet |

| /ʌ/ | ʌ~ɔ | bus, flood, what |

| /ʊ/ | ʊ | book, put, should |

| /uː/ | u~ɵu | food, glue, new |

| Diphthongs | ||

| /aɪ/ | ae~aɪ~æɪ | ride, shine, try |

| ɐɪ~əɪ~ʌɪ | bright, dice, fire | |

| /aʊ/ | äʊ~ɐʊ | now, ouch, scout |

| /eɪ/ | eɪ | lame, rein, stain |

| /ɔɪ/ | ɔɪ | boy, choice, moist |

| /oʊ/ | ʌo~oʊ~o | goat, oh, show |

| R-colored vowels | ||

| /ɑːr/ | aɻ~ɐɻ | barn, car, park |

| /ɪər/ | iɻ~iɚ | fear, peer, tier |

| /ɛər/ | eəɻ~eɻ | bare, bear, there |

| /ɜːr/ | əɻ~ɚ | burn, doctor, first, herd, learn, murder |

| /ər/ | ||

| /ɔːr/ | ɔɻ~oɻ | hoarse, horse, war |

| /ʊər/ | uɻ~oɻ | poor, tour, lure |

| /jʊər/ | jɚ | cure, Europe, pure |

† Footnotes When followed by /r/, the historic /ɒ/ is pronounced entirely differently by Inland North speakers as [ɔ~o], for example, in the words orange, forest, and torrent. The only exceptions to this are the words tomorrow, sorry, sorrow, borrow and, for some speakers, morrow, which use the sound [a~ä̈]. This is all true of General American speakers too. | ||

A Midwestern accent (which may refer to other dialectal accents as well), Chicago accent, or Great Lakes accent are all common names in the United States for the sound quality produced by speakers of this dialect. Many of the characteristics listed here are not necessarily unique to the region and are oftentimes found elsewhere in the Midwest.

Northern Cities Vowel Shift

[edit]

The Northern Cities Vowel Shift or simply Northern Cities Shift is a chain shift of vowels and the defining accent feature of the Inland North dialect region, though it can also be found, variably, in the neighboring Upper Midwest and Western New England accent regions.

Tensing of TRAP and fronting of LOT/PALM

[edit]The first two sound changes in the shift, with some debate about which one led to the other or came first,[16] are the general raising and lengthening (tensing) of the "short a" (the vowel sound of TRAP, typically rendered /æ/ in American transcriptions), as well as the fronting of the sound of LOT or PALM in this accent (typically transcribed /ɑ/) toward [ä] or [a]. Inland Northern TRAP raising was first identified in the 1960s,[17] with that vowel becoming articulated with the tongue raised and then gliding back toward the center of the mouth, thus producing a centering diphthong of the type [ɛə], [eə], or at its most extreme [ɪə]; e.g. naturally . As for LOT/PALM fronting, it can go beyond [ä] to the front [a], and may, for the most advanced speakers, even be close to [æ]—so that pot or sod come to be pronounced how a mainstream American speaker would say pat or sad; e.g. coupon .

Lowering of THOUGHT

[edit]The fronting of the LOT/PALM vowel leaves a blank space that is filled by lowering the "aw" vowel in THOUGHT [ɔ], which itself comes to be pronounced with the tongue in a lower position, closer to [ɑ] or [ɒ]. As a result, for example, people with the shift pronounce caught the way speakers without the shift say cot; thus, shifted speakers pronounce caught as [kʰɑt] (and cot as [kʰat], as explained above).[18] In defiance of the shift, however, there is a well-documented scattering of Inland North speakers who are in a state of transition toward a cot-caught merger; this is particularly evident in northeastern Pennsylvania.[19][20] Younger speakers reversing the fronting of /ɑ/, for example in Lansing, Michigan, also approach a merger.[9]

Backing or lowering of DRESS

[edit]The movement of /æ/ to [ɛə], in order to avoid overlap with the now-fronted /ɑ/ vowel, presumably initiates the consequent shifting of /ɛ/ (the "short e" in DRESS, [ɛ] in General American) away from its original position. Thus, /ɛ/ demonstrates backing, lowering, or a combination of both toward [ɐ], the near-open central vowel, or almost [æ].[9]

Backing of STRUT

[edit]The next change is the movement of /ʌ/ (the STRUT vowel) from a central or back position toward a very far back position [ɔ]. People with the shift pronounce bus so that it sounds more like boss to people without the shift.

Backing or lowering of KIT

[edit]The final change is the backing and lowering of /ɪ/, the "short i" vowel in KIT, toward the schwa /ə/. Alternatively, KIT is lowered to [e], without backing. This results in a considerable phonetic overlap between /ɪ/ and /ə/, although there is no phonemic KIT–COMMA merger because the weak vowel merger is not complete ("Rosa's" /ˈroʊzəz/, with a morpheme-final mid schwa [ə] is distinct from "roses" /ˈroʊzɪz/, with an unstressed allophone of KIT that is phonetically near-close central [ɨ]).[21]

Vowels before /r/

[edit]Before /r/, only /ɑ/ undergoes the Northern Cities Vowel Shift, so that the vowel in start /stɑrt/ varies much like the one in lot /lɑt/ described above. The remaining /ɔ/, /ɛ/ and /ɪ/ retain values similar to General American (GA) in this position, so that north /nɔrθ/, merry /ˈmɛri/ and near /nɪr/ are pronounced [noɹθ, ˈmɛɹi, niɹ], with unshifted THOUGHT (though somewhat closer than in GA), DRESS and KIT (as close as in GA). Inland Northern American English features the north-force merger, the Mary-marry-merry merger, the mirror–nearer and /ʊr/–/ur/ mergers, the hurry-furry merger, and the nurse-letter merger, all of which are also typical of GA varieties.[22]

History of the Northern Cities Vowel Shift

[edit]William Labov et al.'s Atlas of North American English (2006) presents the first historical understanding of the order in which the Inland North's vowels shifted. Speakers around the Great Lakes began to pronounce the short a sound, /æ/ as in TRAP, as more of a diphthong and with a higher starting point in the mouth, causing the same word to sound more like "tray-ap" or "tray-up"; Labov et al. assume that this began by the middle of the 19th century.[23] After roughly a century following this first vowel change—general /æ/ raising—the region's speakers, around the 1960s, then began to use the newly opened vowel space, previously occupied by /æ/, for /ɑ/ (as in LOT and PALM); therefore, words like bot, gosh, or lock came to be pronounced with the tongue extended farther forward, thus making these words sound more like how bat, gash, and lack sound in dialects without the shift. These two vowel changes were first recognized and reported in 1967.[6] While these were certainly the first two vowel shifts of this accent, and Labov et al. assume that /æ/ raising occurred first, they also admit that the specifics of time and place are unclear.[24] In fact, real-time evidence of a small number of Chicagoans born between 1890 and 1920 suggests that /ɑ/ fronting occurred first, starting by 1900 at the latest, and was followed by /æ/ raising sometime in the 1920s.[16]

During the 1960s, several more vowels followed suit in rapid succession, each filling in the space left by the last, including the lowering of /ɔ/ as in THOUGHT, the backing and lowering of /ɛ/ as in DRESS, the backing of /ʌ/ as in STRUT (first reported in 1986),[25] and the backing and lowering of /ɪ/ as in KIT, often but not always in that exact order. Altogether, this constitutes the Northern Cities Shift, identified by linguists as such in 1972.[14]

Possible motivations for the Shift

[edit]Migrants from all over the Northeastern U.S. traveled west to the rapidly industrializing Great Lakes area in the decades after the Erie Canal opened in 1825, and Labov suggests that the Inland North's general /æ/ raising originated from the diverse and incompatible /æ/ raising patterns of these various migrants mixing into a new, simpler pattern.[26] He posits that this hypothetical dialect-mixing event, which initiated the larger Northern Cities Shift (NCS), occurred by about 1860 in upstate New York,[27] and the later stages of the NCS are merely those that logically followed (a "pull chain"). More recent evidence suggests that German-accented English helped to greatly influence the Shift, because German speakers tend to pronounce the English TRAP vowel as [ɛ] and the LOT/PALM vowel as [ä~a], both of which resemble NCS vowels, and there were more speakers of German in the Erie Canal region of upstate New York in 1850 than there were of any single variety of English.[28] There is also evidence for an alternative theory, according to which the Great Lakes area—settled primarily by western New Englanders—simply inherited Western New England English and developed that dialect's vowel shifts further. 20th-century Western New England English variably showed NCS-like TRAP and LOT/PALM pronunciations, which may have already existed among 19th-century New England settlers, though this has been contested.[28] Another theory, not mutually exclusive with the others, is that the Great Migration of African Americans intensified White Northerners' participation in the NCS in order to differentiate their accents from Black ones.[29]

Reversals of the Shift

[edit]Recent evidence suggests that the Shift has largely begun to reverse in many cities of the Inland North,[9][10] such as Lansing,[9] Ogdensburg, Rochester, Syracuse,[10][30][31] Detroit, Buffalo, Chicago, and Eau Claire.[11] In particular, /ɑ/ fronting and /æ/ raising (though raising is persisting before nasal consonants, as is the General American norm) have now reversed among younger speakers in these areas. Several possible reasons have been proposed for the reversal, including growing stigma connected with the accent and the working-class identity it represents.[32]

Other phonetics

[edit]- Rhoticity: As in General American, Inland North speech is rhotic, and the r sound is typically the retroflex [ɻ] or perhaps, more accurately, a bunched or molar [ɹ].

- Canadian raising: The raising of the tongue for the nucleus of the gliding vowel /aɪ/ is found in the Inland North when the vowel sound appears before any voiceless consonant, thus distinguishing, for example, between rider and writer by vowel quality ().[33] In the Inland North, unlike some other dialects, the raising occurs even before certain voiced consonants, including in the words fire, tiger, iron, and spider. When it is not subject to raising, the nucleus of /aɪ/ is pronounced with the tongue further to the front of the mouth than most other American dialects, as [a̟ɪ] or [ae]; however, in the Inland North speech of Pennsylvania, the nucleus is centralized as in General American, thus: [äɪ].[34]

- The nucleus of /aʊ/ may be more backed than in other common North American accents (toward [ɐʊ] or [ɑʊ]).

- The nucleus of /oʊ/ (as in go and boat), like /aʊ/, tends to be conservative, not undergoing the fronting common in the vast American southeastern super-region. Likewise, the traditionally high back vowel /u/ is conservative, less fronted in the North than in other American regions, though it still undergoes some fronting after coronal consonants.[35] Also, /oʊ/, along with /eɪ/, can traditionally manifest as monophthongs: [e] and [o], respectively.[36]

- The vowel in /ɛg/ can raise toward [e] in words like beg, negative, or segment, except in Michigan.[37]

- Working-class th-stopping: The two sounds represented by the spelling th—/θ/ (as in thin) and /ð/ (as in those)—may shift from fricative consonants to stop consonants among urban and working-class speakers: thus, for example, thin may approach the sound of tin (using [t]) and those may merge to the sound of doze (using [d]).[38] This was parodied in the Saturday Night Live comedy sketch "Bill Swerski's Superfans," in which characters hailing from Chicago pronounce "The Bears" as "Da Bears."[39]

- Caramel is typically pronounced with two syllables as carmel.[40]

Vocabulary

[edit]Note that not all of these terms, here compared with their counterparts in other regions, are necessarily unique only to the Inland North, though they appear most strongly in this region:[40]

- boulevard as a synonym for island (in the sense of a grassy area in the middle of some streets)

- crayfish for a freshwater crustacean

- drinking fountain as a synonym for water fountain

- expressway as a synonym for highway

- faucet for an indoor water tap (not Southern spigot)

- goose pimples as a synonym for goose bumps

- pit for the seed of a peach (not Southern stone or seed)

- pop for a sweet, bubbly soft drink (not Eastern and Californian soda, nor Southern coke)

- The "soda/pop line" has been found to run through Western New York State (Buffalo residents say pop, Syracuse residents say soda now but used to say pop until sometime in the 1970s, and Rochester residents say either. Eastern Wisconsinites around Milwaukee and some Chicagoans are also an exception, using the word soda.)

- sucker for a lollipop (hard candy on a stick)

- teeter totter as a synonym for seesaw

- tennis shoes for generic athletic shoes (not Northeastern sneakers, except in New York State and Pennsylvania)

Individual cities and sub-regions also have their own terms; for example:

- bubbler, in a large portion of Wisconsin around Milwaukee, for water fountain (in addition to the synonym drinking fountain, also possible throughout the Inland North)

- cash station, in the Chicago area, for ATM

- Devil's Night, particularly in Michigan, for the night before Halloween (not Northeastern Mischief Night)[41]

- doorwalls, in Detroit, for sliding glass doors

- gapers' block or gapers' delay, in Chicago, Milwaukee and Detroit; or gawk block, in Detroit, for traffic congestion caused by rubbernecking

- gym shoes, in Chicago and Detroit, for generic athletic shoes

- party store, in Michigan, for a liquor store

- rummage sale, in Wisconsin, as a synonym for garage sale or yard sale

- treelawn, in Cleveland and Michigan; devilstrip or devil's strip in Akron, Ohio;[42] and right-of-way in Wisconsin and parkway in Chicago for the grass between the sidewalk and the street

- yous(e) or youz, in northeastern Pennsylvania around its urban center of Scranton, for you guys; in this sub-region, there is notable self-awareness of the Inland Northern dialect (locally called by various names, including "Coalspeak").[43] Youse is also found in Chicago and its hinterland, utilized as a second-person plural pronoun (similar to "y'all").

Notable lifelong native speakers

[edit]- Hillary Clinton – "playing down her flat Chicago accent"[44]

- Ron Coomer – "his South Side accent"[45]

- Joan Cusack – "a great distinctive voice" she says is due to "my Chicago accent... my A's are all flat"[46]

- Richard M. Daley – "makes no effort to tame a thick Chicago accent"[47]

- Jimmy Dore – "I think that Chicago comics like Jimmy Dore bring my Wisconsin/Chicago accent back with a vengence."[48]

- Kevin Dunn – "a blue-collar attitude and the Chicago accent to match"[49]

- David Draiman – "distinct Chicago accent"[50]

- Rahm Emanuel – "more refined (if still very Chicago)"[51]

- Dennis Farina – "rich Chicago accent"[52]

- Chris Farley – "beatific Wisconsin accent"[53]

- Robert Forster – "accent that sounded like pure Chicago—though he hailed from Rochester, N.Y."[54]

- Dennis Franz – "tough-guy Chicago accent"[55]

- Sean Giambrone – "Sean, whose Chicago accent is thick enough to cut with a knife"[56]

- John Goodman – "Goodman delivered a completely authentic Inland North accent.... It wasn't an act."[57]

- Susan Hawk – "a Midwestern truck driver whose accent and etiquette epitomized the stereotype of the tacky, abrasive, working-class character"[58]

- Mike Krzyzewski[59]

- Dennis Kucinich – "a shining example of Cleveland's version of the Inland North accent"[60]

- Bill Lipinski – "I could live only 100 miles from the gentleman from Illinois (Mr. Lipinski) and he would have an accent and I do not"[61]

- Terry McAuliffe – "that rich, unhelpful Syracuse accent"[62]

- Jim "Mr. Skin" McBride – "a clipped Chicago accent"[63]

- Michael Moore – "a Flintoid, with a nasal, uncosmopolitan accent"[64] and "a recognisable blue-collar Michigan accent"[65]

- Bob Odenkirk[66]

- Suze Orman – "broad, Midwestern accent"[67]

- Iggy Pop – "plainspoken Midwestern accent"[68]

- Paul Ryan – "may be the first candidate on a major presidential ticket to feature some of the Great Lakes vowels prominently"[69]

- Michael Symon – "Michael Symon's local accent gives him an honest, working-class vibe"[70]

- Lily Tomlin – "Tomlin's Detroit accent"[71]

- Gretchen Whitmer – "a Michigan accent probably most detectable when she ... flattens out her 'a' sounds with a nasal twang"[72]

See also

[edit]- List of dialects of the English language

- List of English words from indigenous languages of the Americas

- American English regional differences

- North Central American English

- Western New England English

References

[edit]- ^ Gordon (2004), p. xvi.

- ^ Garn-Nunn, Pamela G.; Lynn, James M. (2004). Calvert's Descriptive Phonetics. Thieme. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-60406-617-3.

- ^ Gordon (2004), p. 297.

- ^ a b Chapman, Kaila (October 25, 2017). The Northern Cities Shift: Minnesota's Ever-Changing Vowel Space (Thesis). Macalester College. p. 41.

The satisfaction of the three NCS measures was found only in the 35-55 year old male speakers. The three male speakers fully participating in the NCS had high levels of education and strong ties to the city

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 276, Chapter 19.

- ^ a b c Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 190.

- ^ "Talking the Tawk". The New Yorker. November 7, 2005. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ^ "Do You Speak American? - Language Change - Vowel Shifting". PBS. 2005.

- ^ a b c d e Wagner, S. E.; Mason, A.; Nesbitt, M.; Pevan, E.; Savage, M. (2016). "Reversal and re-organization of the Northern Cities Shift in Michigan" (PDF). University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics. 22 (2). Article 19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-06-23.

- ^ a b c Driscoll, Anna; Lape, Emma (2015). "Reversal of the Northern Cities Shift in Syracuse, New York". University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics. 21 (2).

- ^ a b Dinkin, Aaron J. (2022). "Generational Phases: Toward the Low-Back Merger in Cooperstown, New York". Journal of English Linguistics. 50 (3): 219–246. doi:10.1177/00754242221108411. ISSN 0075-4242. S2CID 251892218.

- ^ Friedman, Lauren (2015). "A Convergence of Dialects in the St. Louis Corridor". Selected Papers from New Ways of Analyzing Variation. 21 (2). University of Pennsylvania: 43.

- ^ Evanini, Keelan (2008). "A shift of allegiance: The case of Erie and the North / Midland boundary". University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics. 14 (2).

- ^ a b c Sedivy, Julie (March 28, 2012). "Votes and Vowels: A Changing Accent Shows How Language Parallels Politics". Discover. Archived from the original on 2016-01-25. Retrieved 2016-01-24.

- ^ a b Hillenbrand, James M. (2003). "American English: Southern Michigan". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 33 (1): 122. doi:10.1017/S0025100303001221.

- ^ a b McCarthy, Corrine (2010). "The Northern Cities Shift in Real Time: Evidence from Chicago". University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics. 15 (2). Article 12.

- ^ Fasold, Ralph (1969). A Sociolinguistic Study of the Pronunciation of Three Vowels in Detroit Speech. Washington: Center for Applied Linguistics.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 189, Chapter 14.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 61.

- ^ Herold, Ruth (1990). Mechanisms of Merger: The Implementation and Distribution of the Low Back Merger in Eastern Pennsylvania (Ph.D. diss. thesis). Univ. of Pennsylvania.

- ^ Gordon (2004), pp. 294–296.

- ^ Gordon (2004), pp. 294–295.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 192, 195.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 191.

- ^ Labov, William (October 20, 2008). Yankee Cultural Imperialism and the Northern Cities Shift (PowerPoint presentation for paper given at Yale University). University of Pennsylvania. Slide 94.

- ^ Labov, William (2007). "Transmission and Diffusion" (PDF). Language. 83 (2): 344–387. doi:10.1353/lan.2007.0082. S2CID 6255506.

- ^ Castro Calle (2017), pp. 34, 48.

- ^ a b Castro Calle (2017), p. 49.

- ^ Van Herk, Gerard (2008). "Fear of a Black Phonology: The Northern Cities Shift as Linguistic White Flight". University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics. 14 (2). Article 19.

- ^ Thiel, Anja; Dinkin, Aaron (2020). "Escaping the TRAP: Losing the Northern Cities Shift in Real Time". Language Variation and Change. 32 (3): 373–393. doi:10.1017/S0954394520000137. S2CID 187646349.

- ^ Kapner, J. (October 12, 2019). "Snowy Days and Nasal A's: the Retreat of the Northern Cities Shift in Rochester, New York". New Ways of Analyzing Variation (Poster presentation). 48. Eugene, OR.

- ^ Nesbitt, Monica (August 1, 2021). "The Rise and Fall of the Northern Cities Shift: Social and Linguistic Reorganization of TRAP in Twentieth-Century Lansing, Michigan". American Speech. 96 (3): 332–370. doi:10.1215/00031283-8791754. ISSN 0003-1283. S2CID 228971560.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 203–204.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 161.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 187.

- ^ Boberg, Charles (December 4, 2017). "Dialects of North American English". The Handbook of Dialectology. Wiley. p. 457. doi:10.1002/9781118827628.ch26. ISBN 978-1-118-82755-0.

- ^ Stanley, Joseph A. (August 1, 2022). "Regional Patterns in Prevelar Raising". American Speech. 97 (3). Duke University Press: 374–411. doi:10.1215/00031283-9308384. ISSN 0003-1283. S2CID 237766388.

- ^ van den Doel, Rias (2006). How Friendly Are the Natives? An Evaluation of Native-Speaker Judgements of Foreign-Accented British and American English (PDF). Landelijke onderzoekschool taalwetenschap (Netherlands Graduate School of Linguistics). pp. 268–269.

- ^ Salmons, Joseph; Purnell, Thomas (2008). "Contact and the Development of American English" (PDF). In Hickey, Ray (ed.). Handbook of Language Contact. Blackwell.

- ^ a b Vaux, Bert; Golder, Scott (2003). "The Harvard Dialect Survey". Harvard University Linguistics Department. Cambridge, MA. Archived from the original on 2016-04-30.

- ^ Metcalf, A.A. (2000). How We Talk: American Regional English Today. Houghton Mifflin. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-618-04362-0.

- ^ Metcalf, A.A. (2000). How We Talk: American Regional English Today. Houghton Mifflin. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-618-04362-0.

- ^ Feather, Kasey (May 19, 2014). "NEPAisms overlooked in new dictionary entries". The Times-Tribune. Times-Shamrock Communications. Retrieved 2016-11-27.

- ^ Chozick, Amy (December 28, 2015). "How Hillary Clinton Went Undercover to Examine Race in Education". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- ^ Sun-Times Wire (December 12, 2013). "Ron Coomer headed to Cubs radio booth — report". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

- ^ "Joan Cusack on 'Mars Needs Moms,' Raising Kids and Her Famous Brother". Archived from the original on 2022-10-11. Retrieved 2022-10-11.

- ^ Stein, Anne (2003). "The über-mayor: what's behind Daley's longevity". Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ Kashian, Jackie. "TDF Ep 6 - Jimmy Dore and Matt Knudsen". Uncut. Archived from the original on 2022-11-27. Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- ^ Wawzenek, Bryan (May 3, 2014). "10 Actors Who Always Show Up on the Best TV Shows". Diffuser.

- ^ "Disturbed? not if you're David Draiman". Today. The Associated Press. June 15, 2006. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- ^ Moser, Whet (March 29, 2012). "Where the Chicago Accent Comes From and How Politics is Changing It". Chicago Mag. Archived from the original on 2016-01-05. Retrieved 2015-12-27.

- ^ Dennis Farina, 'Law & Order' actor, dies at 69. NBC News. 2013.

- ^ Desowitz, Bill (October 16, 2009). "'Fantastic Mr. Fox' Goes to London". Animation World Network. Archived from the original on 2014-02-27. Retrieved 2016-01-07.

- ^ Moorhead, M.V. (October 31, 2019). "Robert Forster: Recalling a memorable encounter". Wrangler News. Retrieved 2024-02-20.

- ^ "Dennis Franz". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2014.

- ^ Crowder, Courtney (December 9, 2014). "'Normal kid' from Park Ridge lifts 'Goldbergs'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2018-01-06.

- ^ Mcclelland, Edward (November 15, 2016). "The St. Louis Accent: An Explainer". Bloomberg.com. Citylab. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- ^ Media Literacy: A Reader. Peter Lang. 2007. p. 55. ISBN 9780820486680.

- ^ "With Coach K, will USA hoops bring its A game and return to golden Olympic glory?". cleveland.com. July 30, 2008. Retrieved 2023-06-23.

- ^ McIntyre, Michael K. (January 13, 2017). "Clevelanders probably think they don't have an accent, but we do, and so do others in the Midwest". Cleveland.com. Advance Local. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

- ^ Congress, U. S. (November 2009). Congressional Record, V. 150, Pt. 17, October 9 to November 17, 2004. U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780160844164. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ^ Newell, Jim (June 8, 2009). "Hillary All Over Again?". The Daily Beast. The Daily Beast Company. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

- ^ Brooks, Jake (2004). "Mr. Skin Invades Sundance". The New York Observer. Observer Media.

- ^ McClelland, Edward (2013). Nothin' but Blue Skies. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 85. ISBN 9781608195459.

- ^ "Bush fears Moore because he speaks to the heart of America". The Independent. 2004.

- ^ "Fargo's Midwestern Accents, Ranked from Worst to Best". pastemagazine.com. June 21, 2017. Retrieved 2022-07-22.

- ^ Dominus, Susan (2009). "Suze Orman Is Having a Moment". The New York Times.

- ^ AFP (October 14, 2014). "Iggy Pop's advice for young rockers". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- ^ Landers, Peter (October 11, 2012). "Paul Ryan Sounds Radical to Linguists". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2016-01-24.

- ^ "Michael Symon: 2007 winner of 'The Next Iron Chef'". Chicago Tribune. 2015. Archived from the original on 2023-04-05.

- ^ Maupin, Elizabeth (1997). "'Signs': Still Briming With Intelligent Life". Orlando Sentinel.

- ^ Cohn, Jonathan (November 5, 2022). "Gretchen Whitmer Is Both Loved And Hated In Michigan — And Still 'Fighting Like Hell'". Huffpost. BuzzFeed. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

Sources

[edit]- Castro Calle, Yesid (2017). German Echoes in American English: How New-dialect Formation Triggered the Northern Cities Shift (Undergraduate Honors Thesis). Stanford University Department of Linguistics.

- Gordon, Matthew J. (2004). "New York, Philadelphia, and other northern cities: phonology". In Kortmann, Bernd; Burridge, Kate; Mesthrie, Rajend; Schneider, Edgar W.; Upton, Clive (eds.). A Handbook of Varieties of English. Volume 1: Phonology, Volume 2: Morphology and Syntax. Berlin / New York: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110175325.

- Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.

External links

[edit]- Chicago Dialect Samples

- The Guide to Buffalo English. Archived 2010-09-15 at the Wayback Machine.

- The Northern Cities Vowel Shift. Archived 2005-11-20 at the Wayback Machine.

- NPR interview with Professor William Labov about the shift

- PBS resource from the show "Do you Speak American?"

- Select Annotated Bibliography On the Speech of Buffalo, NY. Archived 2012-11-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- Telsur Project Maps

Languages in italics are extinct. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| English |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oral Indigenous languages |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manual Indigenous languages |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oral settler languages |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manual settler languages |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Immigrant languages (number of speakers in 2021 in millions) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||