Historical orders of chivalry

The Spanish military orders or Spanish Medieval knights orders are a set of religious-military institutions that emerged during the Reconquista. The most important orders arose in the 12th century in the Crowns of León and Castile (Order of Santiago, Order of Alcántara, and Order of Calatrava) and in the 14th century in the Crown of Aragon (Order of Montesa). These orders were preceded by many others that did not survive, such as the Aragonese Militia Christi of Alfonso of Aragon and Navarre, the Confraternity of Belchite (founded in 1122), or the Military order of Monreal (founded in 1124), which were later refurbished by Alfonso VII of León and Castile. After the refurbishment, these orders took the name of Cesaraugustana and were integrated into the Knights Templar in 1149 with Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona. The Portuguese Order of Aviz responded to identical circumstances in the remaining peninsular Christian kingdom.

During the Middle Ages, native Military orders appeared in the Iberian Peninsula, sharing many similarities with other international Military orders but also possessing unique peculiarities due to the peninsular's historical circumstances marked by the confrontation between Muslim and Christian forces.

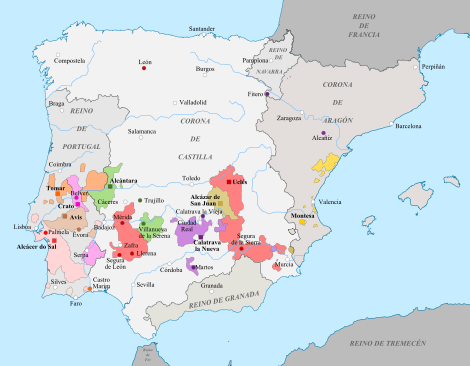

The birth and expansion of these native orders occurred mainly during the Reconquista's stages in which territories south of the Ebro and Tagus were occupied. As a result, their presence in areas such as La Mancha, Extremadura, and Sistema Ibérico (Campo de Calatrava, Maestrazgo, etc.) came to define the main feature of Repoblación, with each Order exercising a political and economic role similar to that of a feudal manor through their encomiendas. Simultaneously, the presence of foreign military orders such as the Templar or the Saint John was notable. However, the suppression of the Knights Templar in the 14th century benefited Spain significantly.

The military orders' social implementation among noble families was significant, extending even through related female orders such as Comendadoras de Santiago and others similar.

After the turbulent period of the late medieval crisis—in which the position of Grand Master of the orders was the subject of violent disputes between the aristocracy, the monarchy and the favourites (infantes of Aragon, Álvaro de Luna, etc.)—Ferdinand II of Aragon, in the late 15th century, managed to neutralize the orders politically to obtain the papal concession of the unification in the person of that position for all of them, and its joint inheritance for its heirs, the kings of the later Catholic Monarchy, that administered through the Royal Council of the Military Orders.

Gradually losing any military function along the Antiguo Régimen, the territorial wealth of the military orders was the subject of confiscation in the 19th century, which reduced the orders thereafter to the social function of representing, as honorary positions, an aspect of noble status.[1]

Birth and evolution

Although the appearance of the Hispanic military orders can be interpreted as pure imitation of the international arisen following the Crusades, both its birth and its subsequent evolution have distinctive features, as they played a leading role in the struggle of Christian kingdoms against the Muslims, in the repopulation of large territories, especially between the Tagus and the Guadalquivir and became a political and economic force of the first magnitude, besides having great role in the noble struggles held between the 13th and 15th centuries, when finally the Catholic Monarchs managed to gain its control.

For the Arabists, the birth of the Spanish military orders was inspired by the Muslims' ribat, but other authors believe that its appearance was the result of a merger of confraternities and council militias tinged with religiosity, by absorption and concentration gave rise to the large orders at a time when the struggle against Almohad power required every effort by the Christian side.[citation needed][neutrality is disputed]

Traditionally it is accepted that the first to appear was that of Order of Calatrava, born in that village of the Castilian kingdom in 1158, followed by that of Order of Santiago, founded in Cáceres, in the Leonese kingdom, in 1170. Six years later was created the Order of Alcántara, initially called ¨of San Julián del Pereiro¨. The last to appear was the Order of Montesa it did later on, during the 14th century, in the Crown of Aragon due to the dissolution of the Order of the Templar.

Hierarchical organization

Imitating the international orders, the Spanish adopted their organization. The master was the highest authority of the order, with almost absolute power, both militarily, and politically or religiously. It was chosen by the council, made up of thirteen friars, where it comes to its components the name of "Thirteens". The office of Master is life-time and in his death, the Thirteen, convened by the greater prior of the order, choose the new. It should be the removal of the master by incapacity or pernicious conduct for the order. To carry out it needed the agreement of its governing bodies: council of the thirteen, "greater prior" and "greater convent".

The General Chapter is a kind of representative assembly that controls the entire order. What are the thirteen, the priors of all the convents and all commanders. It should meet annually a certain day in the greater convent, although in the practice these meetings were held where and when the master wanted.

In each kingdom was a "greater commander", based in a town or fortress. The priors of each convent were elected by the canons, because it must bear in mind that within the orders were freyles milites (knights) and freyles clérigos, professed monks who taught and administering the sacraments.

Territorial organization

the end of 15th century:

Residence of the Grand Master

Residence of the Grand MasterDue to their dual nature as both military and religious institutions, the orders developed separate double organizations for each of these areas, though they were not always completely detached.

In the political-military area, the orders were divided into "major encomiendas", with each peninsular kingdom having a greater encomienda in which the order was present. The main commander was in charge of them. Below the major encomiendas were the encomiendas, which were a collection of goods, not always territorial or grouped, but generally constituted territorial demarcations. The encomiendas were administered by a commander. The fortresses not under the command of the commander were headed by an alcaide appointed by him.

Religiously, the orders were organized by convents, with a main convent serving as the headquarters of the order. The Order of Santiago was based in Uclés, following the rifts of the order with the Leonese monarch Ferdinand II. The Order of Alcántara was based in the Extremaduran village that gave it its name.

The convents were not only places where the professed monks lived, but also constituted priories, religious territorial demarcations where the respective priors had the same powers as the bishoprics, resulting in the military orders being removed from the episcopal power in extensive territories.

Army

The command of the army was exercised by the highest dignitaries of each order. At the apex was the master, followed by the main commanders. The figure of alférez was highlighted at the beginning, but in the Middle Ages it had disappeared. The command of the fortresses was in the hands of the commander or an alcaide appointed by him.

Recruitment was done through encomiendas, with each presumably contributing a number of lances or men related to the economic value of the demarcation.

Of note is the surprising bellicosity of the orders and their rigorous promise to fight the infidel, which often manifested itself in the continuation of authentic "private wars" against the Muslims when, for various reasons, the Christian kings gave up the struggle. This was due to signing truces or directing their military actions in other ways, as was the case when Ferdinand III of Castile, crowned king of León, abandoned the interests of this kingdom to pursue the conquest of Andalusia in favor of the Crown of Castile.

Repopulation and social policy

The military orders played an important role not only in military affairs, but also in repopulation, economic growth, and social development. Simply conquering territory was not enough; it was also necessary to attract settlers and develop the land for defense and economic purposes.

The orders received vast tracts of land, which they used to gain political and economic power through repopulation efforts. They employed various methods to attract people to the newly acquired lands, such as granting generous fueros (legal codes) to villages under their jurisdiction. They often modeled their fueros on more generous ones, like those of Cáceres and Sepúlveda. The tax exemptions by marriage from the Fuero of Usagre were also implemented.

In addition, the orders sought to develop unproductive lands. To this end, they provided incentives for new settlers, such as donations of public lands and the organization of fairs. They also undertook significant infrastructure projects to improve communication networks, such as building bridges and roads, which in turn facilitated trade. The tax-free nature of the fairs was particularly attractive to merchants and helped stimulate economic growth in the region.

Relations with other institutions

The Hispanic military orders had diverse relationships with other powers and institutions. They generally received support from the papacy, as they constituted a strong foundation for the reconquest and directly depended on its authority. The Popes granted episcopal authority to the priors of the orders in their conflict with the bishops, providing them greater independence.

The relationship between the Hispanic military orders and other powers and institutions underwent several changes during different stages. Initially, monarchs recognized the potential of the orders in the reconquest and repopulation tasks and saw them as the "most precious jewel" of their crowns. Kings such as Alfonso of Aragon and Navarre and Alfonso VIII of Castile enticed the orders to their kingdoms by offering possessions and territories. Besides military or political donations, kings also granted tax privileges and favored the orders in numerous lawsuits with other powers. In return, the orders were loyal to the monarchs and carried out the missions entrusted to them. However, with the increasing power of the orders, monarchs such as Alfonso XI of Castile began a struggle to gain control through the designation of the master. This struggle continued until the Catholic Monarchs achieved absolute control over the orders' mastership, which became hereditary.

The relationship between the orders and the concejos of realengo, especially those endowed with extensive domains of difficult control and occupation, was problematic. The orders often preyed upon unpopulated areas until the kings put an end to their usurpations. However, from the 14th century, these councils suffered the same predation by lay lords. Disputes with neighbors also led to prolonged and even physical confrontations.

The relationship with the rest of the clergy was equally diverse. While some clergy supported the orders, there were also endless lawsuits and skirmishes, such as the attack on the bishops of Cuenca and Sigüenza by the Santiago's commander of Uclés. Tensions with the bishops were frequent in the struggle for ecclesiastical jurisdiction, which were subtracted from the priors, who finally received papal support.

The orders maintained brotherhood and coordination in their relations with each other. Calatrava and Alcántara were united by relations of affiliation without incurring a lack of autonomy of Alcántara. The orders had agreements for mutual aid and sharing of archives. For instance, the tripartite agreement of friendship, mutual defense, coordination, and centralization was signed in 1313 by Santiago, Calatrava, and Alcántara.

Dissolution

The Military Orders were dissolved on April 29 of 1931 by the Republican government.

During the Spanish Civil War, many non-militant, non-criminal, civilian leading members of the Orders were killed, their knights in the crosshairs of ideological revolutionists, put to death for revolutionary agendas: minimally, at least nineteen of the Military Order of Santiago, fifteen of the Military Order of Calatrava, five of the Military Order of Alcántara and four of the Military Order of Montesa were executed. These numbers are conservative in fact and unconfirmed, but doubtless, ideologically-inspired killings of those with serious ties to these Orders, existed beyond official recorded numbers – regardless of class, any persons intimately associated with these pre-modern Orders were targets of revolutionary assassinations and the death-toll was likely higher.

The "officially" tabulated balance of Knights of 1931 to 1935 in the midst of the chaos was as follows:

- Military Order of Santiago, 68 of 116.

- Military Order of Calatrava, 89 of 139.

- Military Order of Alcántara, 19 of 42.

- Military Order of Montesa, 51 of 70.

In 1985 only 19 documentation-verified knights, who professed a dedication before approximately 1931, remained of what was once a grand edifice of social significance to Spanish and greater European society.

Revival

After the Spanish Civil War, negotiations began with Franco, the caudillo whose social policy aimed to synthesize modernity with traditional elements of redeeming value. He invited Bishop-Prior Emeterio Echeverría Barrena to an exchange, but it was unproductive, and the Order subsisted marginally or informally over the following years. It was not until April 2, 1980, when they were officially recorded as an association by the Civil Government of Madrid. On May 26 of the same year, they were registered as a federation. The Order of Santiago, along with Calatrava, Alcántara, and Montesa, were reinstated as civil associations during the reign of Juan Carlos I, as honorable and religious noble organizations, which they remain today.

On April 9, 1981, after fifty years, Juan Carlos I named his father, Infante Juan of Bourbon, President of the Royal Council of the Military Orders. Currently, As of April 28, 2014[update], the position of President of the Royal Council is held by Don Pedro of Bourbon, Duke of Noto.

List

- Medieval knights orders founded in Spain (arranged in alphabetic order)[a]

- Female orders

Most were honorific orders in payment of efforts by warrior girls attacking Muslims (and in some cases attacking English), and their high contribution to the reconquest of cities, some however came to become actually in female military orders.[16]

| Emblem | Name | Founded | Founder | Origin | Recognition | Protection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female order of the Band | 1387 | John I of Castile | Palencia, Castile and León (Crown of Castile) | Crown of Castile (1387– )[16] | ||

| Female order of the Hatchet | 1149 | Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona | Tortosa, Catalonia (County of Barcelona) | County of Barcelona (1149– )[17] | ||

| Order of Santiago | 1151 | Ferdinand II of León and Pedro Suárez de Deza | Uclés, Castile-La Mancha (Kingdom of Castile) and León, Castile and León (Kingdom of León) | July 5, 1175 by Pope Alexander III, Pope Urban III, Pope Innocent III | Kingdom of León (1158– ), Kingdom of Castile (1158– )[12] |

- Both Medieval naval and knights orders, fulfilling dual function, but mainly naval

| Emblem | Name | Founded | Founder | Origin | Recognition | Protection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Order of Saint Mary of Spain | 1270 | Alfonso X of Castile | Cartagena, Region of Murcia (Crown of Castile) | Crown of Castile (1177– )[18] |