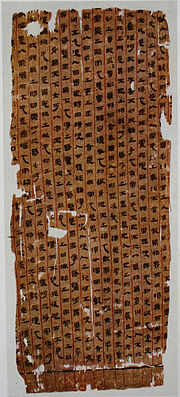

Ink on silk manuscript of the Tao Te Ching, 2nd century BC, unearthed from Mawangdui | |

| Author | Laozi (trad.) |

|---|---|

| Original title | 道德經 |

| Language | Classical Chinese |

| Genre | Philosophy |

Publication date | 4th century BC |

| Publication place | China |

Published in English | 1868 |

Original text | 道德經 at Chinese Wikisource |

| Translation | Tao Te Ching at Wikisource |

| Other names | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laozi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 老子 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wade–Giles | Lao3 Tzŭ3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Lǎozǐ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Old Master" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5000-Character Classic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 五千文 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wade–Giles | Wu3 Ch'ien1 Wên2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Wǔqiān Wén | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "The 5000 Characters" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

The Tao Te Ching[note 1] (traditional Chinese: 道德經; simplified Chinese: 道德经) is a Chinese classic text and foundational work of Taoism traditionally credited to the sage Laozi,[7][8] though the text's authorship, date of composition and date of compilation are debated.[9] The oldest excavated portion dates to the late 4th century BCE,[10] but modern scholarship dates other parts of the text as having been written—or at least compiled—later than the earliest portions of the Zhuangzi.[11]

The Tao Te Ching is central to both philosophical and religious conceptions of Taoism, and has had great influence beyond Taoism as such on Chinese philosophy and religious practice throughout history. Terminology originating in the Tao Te Ching has been reinterpreted and elaborated upon by Legalist thinkers, Confucianists, and particularly Chinese Buddhists, which had been introduced to China significantly after the initial solidification of Taoist thought. It is comparatively well known in the West, and one of the most translated texts in world literature.[10]

In English, the title is commonly rendered Tao Te Ching, following the Wade–Giles romanisation, or as Daodejing, following pinyin. It can be translated as The Classic of the Way and its Power,[12] The Book of the Tao and Its Virtue,[13] The Book of the Way and of Virtue,[14][15] The Tao and its Characteristics,[5] The Canon of Reason and Virtue,[6] The Classic Book of Integrity and the Way,[16] or A Treatise on the Principle and Its Action.[17][18]

Ancient Chinese books were commonly referenced by the name of their real or supposed author, in this case the "Old Master",[19] Laozi. As such, the Tao Te Ching is also sometimes referred to as the Laozi, especially in Chinese sources.[10]

The title Tao Te Ching, designating the work's status as a classic, was only first applied during the reign of Emperor Jing of Han (157–141 BC).[20] Other titles for the work include the honorific Sutra of the Way and Its Power (道德真經; Dàodé zhēnjing) and the descriptive Five Thousand Character Classic (五千文; Wǔqiān wén).

The Tao Te Ching has a long and complex textual history. Known versions and commentaries date back two millennia, including ancient bamboo, silk, and paper manuscripts discovered in the twentieth century.[citation needed]

The Tao Te Ching is a text of around 5,000 Chinese characters in 81 brief chapters or sections (章). There is some evidence that the chapter divisions were later additions—for commentary, or as aids to rote memorisation—and that the original text was more fluidly organised. It has two parts, the Tao Ching (道經; chapters 1–37) and the Te Ching (德經; chapters 38–81), which may have been edited together into the received text, possibly reversed from an original Te Tao Ching. The written style is laconic, has few grammatical particles, and encourages varied, contradictory interpretations. The ideas are singular; the style is poetic. The rhetorical style combines two major strategies: short, declarative statements and intentional contradictions. The first of these strategies creates memorable phrases, while the second forces the reader to reconcile supposed contradictions.[21]

The Chinese characters in the original versions were probably written in seal script, while later versions were written in clerical script and regular script styles.[citation needed]

The Tao Te Ching is ascribed to Laozi, whose historical existence has been a matter of scholarly debate. His name, which means "Old Master", has only fuelled controversy on this issue.[22]

The first biographical reference to Laozi is in the Records of the Grand Historian,[23] by Chinese historian Sima Qian (c. 145–86 BC), which combines three stories.[24] In the first, Laozi was a contemporary of Confucius (551–479 BC). His surname was Li (李), and his personal name was Er (耳) or Dan (聃). He was an official in the imperial archives, and wrote a book in two parts before departing to the West; at the request of the keeper of the Han-ku Pass, Yinxi, Laozi composed the Tao Te Ching. In the second story, Laozi, also a contemporary of Confucius, was Lao Laizi (老莱子), who wrote a book in 15 parts. Third, Laozi was the grand historian and astrologer Lao Dan (老聃), who lived during the reign of Duke Xian of Qin (r. 384–362 BC).[citation needed]

The pronunciation of Old Chinese spoken contemporaneously with the Tao Te Ching's composition has been partially reconstructed. Approximately three-quarters of the lines of Tao Te Ching rhymed in the original language.[25]

Generations of scholars have debated the historicity of Laozi and the dating of the Tao Te Ching. Linguistic studies of the text's vocabulary and rhyme scheme point to a date of composition after the Classic of Poetry, yet before the Zhuangzi. Legends claim variously that Laozi was "born old" and that he lived for 996 years, with twelve previous incarnations starting around the time of the Three Sovereigns before the thirteenth as Laozi. Some scholars have expressed doubts over Laozi's historicity.[26]

Many Taoists venerate Laozi as the founder of the school of Tao, the Daode Tianzun in the Three Pure Ones, and one of the eight elders transformed from Taiji in the Chinese creation myth.[citation needed]

The predominant view among scholars today is that the text is a compilation or anthology representing multiple authors. The current text might have been compiled c. 250 BCE, drawn from a wide range of versions dating back a century or two.[27]

Among the many transmitted editions of the Tao Te Ching text, the three primary ones are named after early commentaries. The "Yan Zun Version", which is only extant for the Te Ching, derives from a commentary attributed to Han dynasty scholar Yan Zun (巖尊, fl. 80 BC – 10 AD). The "Heshang Gong" version is named after the legendary Heshang Gong ('legendary sage'), who supposedly lived during the reign of Emperor Wen of Han (180–157 BC). This commentary has a preface written by Ge Xuan (164–244 AD), granduncle of Ge Hong, and scholarship dates this version to c. the 3rd century AD. The origins of the "Wang Bi" version have greater verification than either of the above. Wang Bi (226–249 AD) was a Three Kingdoms-period philosopher and commentator on the Tao Te Ching and I Ching.[citation needed]

Tao Te Ching scholarship has advanced from archaeological discoveries of manuscripts, some of which are older than any of the received texts. Beginning in the 1920s and 1930s, Marc Aurel Stein and others found thousands of scrolls in the Mogao Caves near Dunhuang. They included more than 50 partial and complete manuscripts. One written by the scribe So/Su Dan (素統) is dated to 270 AD and corresponds closely with the Heshang Gong version. Another partial manuscript has the Xiang'er commentary, which had previously been lost.[28]: 95ff [29]

In 1973, archaeologists discovered copies of early Chinese books, known as the Mawangdui Silk Texts, in a tomb dated to 168 BC.[10] They included two nearly complete copies of the text, referred to as Text A (甲) and Text B (乙), both of which reverse the traditional ordering and put the Te Ching section before the Tao Ching, which is why the Henricks translation of them is named "Te-Tao Ching". Based on calligraphic styles and imperial naming taboo avoidances, scholars believe that Text A can be dated to about the first decade and Text B to about the third decade of the 2nd century BC.[30]

In 1993, the oldest known version of the text, written on bamboo slips, was found in a tomb near the town of Guodian (郭店) in Jingmen, Hubei, and dated prior to 300 BC.[10] The Guodian Chu Slips comprise around 800 slips of bamboo with a total of over 13,000 characters, about 2,000 of which correspond with the Tao Te Ching.[10]

Both the Mawangdui and Guodian versions are generally consistent with the received texts, excepting differences in chapter sequence and graphic variants. Several recent Tao Te Ching translations utilise these two versions, sometimes with the verses reordered to synthesize the new finds.[31]

|

See also: Laozi § Tao Te Ching |

The Tao Te Ching describes the Tao as the source and ideal of all existence: it is unseen, but not transcendent, immensely powerful yet supremely humble, being the root of all things. People have desires and free will (and thus are able to alter their own nature). Many act "unnaturally", upsetting the natural balance of the Tao. The Tao Te Ching intends to lead students to a "return" to their natural state, in harmony with Tao.[32] Language and conventional wisdom are critically assessed. Taoism views them as inherently biased and artificial, widely using paradoxes to sharpen the point.[33]

Wu wei, literally 'non-action' or 'not acting', is a central concept of the Tao Te Ching. The concept of wu wei is multifaceted, and reflected in the words' multiple meanings, even in English translation; it can mean "not doing anything", "not forcing", "not acting" in the theatrical sense, "creating nothingness", "acting spontaneously", and "flowing with the moment".[34]

This concept is used to explain ziran, or harmony with the Tao. It includes the concepts that value distinctions are ideological and seeing ambition of all sorts as originating from the same source. Tao Te Ching used the term broadly with simplicity and humility as key virtues, often in contrast to selfish action. On a political level, it means avoiding such circumstances as war, harsh laws and heavy taxes. Some Taoists see a connection between wu wei and esoteric practices, such as zuowang ('sitting in oblivion': emptying the mind of bodily awareness and thought) found in the Zhuangzi.[33]

The Tao Te Ching has been translated into Western languages over 250 times, mostly to English, German, and French.[35] According to Holmes Welch, "It is a famous puzzle which everyone would like to feel he had solved."[36] The first English translation of the Tao Te Ching was produced in 1868 by the Scottish Protestant missionary John Chalmers, entitled The Speculations on Metaphysics, Polity, and Morality of the "Old Philosopher" Lau-tsze.[37] It was heavily indebted[38] to Julien's French translation[14] and dedicated to James Legge,[4] who later produced his own translation for Oxford's Sacred Books of the East.[5]

Other notable English translations of the Tao Te Ching are those produced by Chinese scholars and teachers: a 1948 translation by linguist Lin Yutang, a 1961 translation by author John Ching Hsiung Wu, a 1963 translation by sinologist Din Cheuk Lau, another 1963 translation by professor Wing-tsit Chan, and a 1972 translation by Taoist teacher Gia-Fu Feng together with his wife Jane English.

Many translations are written by people with a foundation in Chinese language and philosophy who are trying to render the original meaning of the text as faithfully as possible into English. Some of the more popular translations are written from a less scholarly perspective, giving an individual author's interpretation. Critics of these versions claim that their translators deviate from the text and are incompatible with the history of Chinese thought.[39] Russell Kirkland goes further to argue that these versions are based on Western Orientalist fantasies and represent the colonial appropriation of Chinese culture.[40][41] Other Taoism scholars, such as Michael LaFargue[42] and Jonathan Herman,[43] argue that while they do not pretend to scholarship, they meet a real spiritual need in the West. These Westernized versions aim to make the wisdom of the Tao Te Ching more accessible to modern English-speaking readers by, typically, employing more familiar cultural and temporal references.

The Tao Te Ching is written in Classical Chinese, which generally poses a number of challenges for interpreters and translators. As Holmes Welch notes, the written language "has no active or passive, no singular or plural, no case, no person, no tense, no mood."[44] Moreover, the received text lacks many grammatical particles which are preserved in the older Mawangdui and Beida texts, which permit the text to be more precise.[45] Lastly, many passages of the Tao Te Ching are deliberately ambiguous.[46][47]

Since there is very little punctuation in Classical Chinese, determining the precise boundaries between words and sentences is not always trivial. Deciding where these phrasal boundaries are must be done by the interpreter.[46] Some translators have argued that the received text is so corrupted due to[citation needed] its original medium being bamboo strips[48] linked with silk threads—that it is impossible to understand some passages without some transposition of characters.[citation needed]