His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada | |

|---|---|

A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami in Germany, 1974 | |

| Title | Founder-Acharya of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness |

| Personal | |

| Born | Abhay Charan De 1 September 1896 |

| Died | 14 November 1977 (aged 81) |

| Resting place | Srila Prabhupada's Samadhi Mandir, ISKCON Vrindavan 27°34′19″N 77°40′38″E / 27.57196°N 77.67729°E |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Parents |

|

| Denomination | Gaudiya Vaishnavism |

| Lineage | from Chaitanya Mahaprabhu |

| Notable work(s) |

|

| Alma mater | Scottish Churches College, University of Calcutta[2] |

| Known for | the Hare Krishna movement[1] |

| Signature | |

| Religious career | |

| Guru | Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakur |

| Initiation | diksha: 1933 (by Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati) sannyasa: 1959 (by Bhakti Prajnan Keshava) |

A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (IAST: Abhaya Caraṇāravinda Bhaktivedānta Svāmī Prabhupāda; Bengali: অভয চরণারৱিন্দ ভক্তিৱেদান্ত স্ৱামী প্রভুপাদ) (1896–1977) was a spiritual, philosophical, and religious teacher from India who spread the Hare Krishna mantra and the teachings of “Krishna consciousness” to the world. Born as Abhay Charan De and later legally named Abhay Charanaravinda Bhaktivedanta Swami, he is often referred to as “Bhaktivedanta Swami”, "Srila Prabhupada", or simply “Prabhupada”.[3]

To carry out an order received in his youth from his spiritual teacher to spread “Krishna consciousness” in English, in his old age, at 69, he journeyed in 1965 from Kolkata to New York City on a cargo ship, taking with him little more than a few trunks of books. He knew no one in America, but he chanted Hare Krishna in a park in New York City, gave classes, and in 1966, with the help of some early students, established the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), which now has centers throughout the world.

He taught a path in which one aims at realizing oneself to be an eternal spiritual being, distinct from one’s temporary material body, and seeks to revive one’s dormant relationship with the supreme living being, known by the Sanskrit name Krishna. One does this through various practices, especially through hearing about Krishna from standard texts, chanting mantras consisting of names of Krishna, and adopting a life of devotional service to Krishna. As part of these practices, Prabhupada required that his initiated students strictly refrain from gambling, eating meat, fish, and eggs, using intoxicants (even coffee, tea, or cigarettes), and engaging in extramarital sex. In contrast to earlier Indian teachers who had promoted in the West the idea that the ultimate truth is essentially impersonal, he taught that the Absolute is ultimately personal.

His duty as a guru, or teacher, he held, was to convey intact the message of Krishna as found in core spiritual texts such as the Bhagavad Gita. To this end, he wrote and published a translation and commentary he called Bhagavad-gita As It Is. He also wrote and published translations and commentaries for texts celebrated in India but hardly known elsewhere, such as the Srimad-Bhagavatam (Bhagavata Purana) and the Chaitanya Charitamrita, thereby making those texts accessible in English for the first time. In all, he wrote more than eighty books.

In the late 1970s and the 1980s ISKCON came to be labeled a destructive cult by critics in America and some European countries. Although scholars and courts rejected claims of cultic brainwashing and recognized ISKCON as representing an authentic branch of Hinduism, in some places the “cult” label and image have persisted. Some of Prabhupada's views or statements have been perceived as racist towards blacks, discriminatory against lower castes, or misogynistic.[4][5][6] Decades after his demise, Prabhupada's teachings and the Society he established continue to be influential,[7] with some scholars and Indian political leaders calling him one of the most successful propagators of Hinduism abroad.[8][9][10][11]

Abhay Charan De was born in Calcutta (now Kolkata), India, on September 1, 1896, the day after Janmashtami (the birth anniversary of Krishna).[12] His parents, Gour Mohan De and Rajani De, named him Abhay Charan, meaning “one who is fearless, having taken shelter of Lord Krishna’s lotus feet”.[3] Following Indian tradition, Abhay’s father invited an astrologer, who predicted that at the age of seventy, Abhay would cross the ocean,[13] become a famous religious teacher, and open 108 temples around the world.[14]

Abhay was raised in a religious family belonging to the suvarna-vanik mercantile community. His parents were Gaudiya Vaishnavas, or followers of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, who taught that Krishna is the Supreme Personality and that pure love for Krishna is the highest attainment.[15][16]

Gour Mohan was a middle-income merchant and had his own fabric and clothing store.[17] He was related to the rich and aristocratic Mullik mercantile family,[13] who had been trading in gold and salt for centuries.[17]

Opposite the De house was a temple of Radha-Krishna that for a century and a half had been supported by the Mullik family.[17] Every day, young Abhay, accompanied by his parents or servants, attended temple services.[17]

At the age of six, Abhay organized a likeness of the “chariot festival”, or Ratha-yatra, the huge Vaishnava festival held annually in the city of Puri in Odisha.[18] For this purpose, Abhay persuaded his father to obtain for him a scaled-down copy of the massive chariot on which the form of Jagannatha (Krishna as “Lord of the universe”) rides in procession in Puri.[18] Decades later, after going to America, Abhay would bring Ratha-yatra festivals to the West.[19]

Though Abhay’s mother wanted Abhay to go to London to study law,[20] his father rejected the idea, fearing Abhay would be negatively influenced by Western society and acquire bad habits.[12] In 1916 Abhay began his studies at Scottish Church College, a prestigious school in Calcutta founded by Alexander Duff, a Christian missionary.[21][a]

In 1918, while in college, Abhay, as arranged by his father, married Radharani Datta, also from an aristocratic family.[12][18][22] They had five children over the course of their marriage.[16] After graduation from college, Abhay began a career in pharmaceuticals[23] and later opened his own pharmaceutical company in Allahabad.[24]

Abhay grew up while India was under British rule, and like many other youth his age he was attracted to Mahatma Gandhi's non-cooperation movement. In 1920, Abhay graduated from college with a specialization in English, philosophy, and economics.[25] He successfully passed the final exams, but as a sign of opposition to British rule he refused to take part in the graduation ceremony and receive a diploma.[12][22]

In 1922, while still in college, Abhay was persuaded by a friend, Narendranath Mullik,[17] to meet with Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati (1874-1937), a Vaishnava scholar and teacher and the founder of the Gaudiya Math — a spiritual institution for spreading the teachings of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu.[12] The word “math” denotes a monastic or missionary center.[26] Bhaktisiddhanta was continuing the work of his father, Bhaktivinoda Thakur (1838-1914), who regarded Chaitanya's teachings as the highest form of theism, intended not for any one religion or nation but for all of humanity.[23]

When the meeting took place, Bhaktisiddhanta said to Abhay, “You are an educated young man. Why don’t you take the message of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu and spread it in English?”[12][27][28] But Abhay, according to his own later account, argued that India first needed to become independent before anyone would take Chaitanya’s message seriously — an argument Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati defeated.[29] Convinced, Abhay accepted the instruction to spread the message of Chaitanya in English, and it was in pursuance of this order from Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati that he later traveled to New York.[30] Many years later he recalled: “I immediately accepted him as spiritual master. Not formally, but in my heart”.[31]

After meeting Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati in 1922, Abhay had little contact with the Gaudiya Math until 1928, when sannyasis (renounced, itinerant preachers) from the Math came to open a center in Allahabad, where Abhay and his family were living.[32] Abhay became a regular visitor, contributed funds, and brought important people to the lectures of the Math’s sannyasis. In 1932, he visited Bhaktisiddhanta in the holy town of Vrindavan, and in 1933, when Bhaktisiddhanta came to Allahabad to lay the cornerstone for a new temple, Abhay received diksha (spiritual initiation) from him and was given the name Abhay Charanaravinda.[3][32]

Over the next three years, whenever Abhay was able to visit Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati in Calcutta[33] or Vrindavan,[34] Abhay would carefully hear from his spiritual master.[35] In 1935, Abhay moved for business to Bombay[36] and then in 1937 back to Calcutta.[37] In both places he assisted other members of the Gaudiya Math by donating money, leading kirtans, lecturing, writing, and bringing others to the Math. At the end of 1936, he visited Vrindavan, where he again met Bhaktisiddhanta, who told him, “If you ever get money, print books”[18] — an instruction that would inform his life’s work.[citation needed]

Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, two weeks before his death on January 1, 1937, wrote a letter to Abhay urging him to teach Gaudiya Vaishnavism in English.[38][39][40][41] After Bhaktisiddhanta passed away, the unified mission of the Gaudiya Math split,[42] and a battle for power broke out between his senior disciples.[43] Although Abhay continued to serve with other disciples of his spiritual master and wrote articles for their publications, he kept clear of the political struggles.[43][44]

In 1939, elders in the Gaudiya community honored Abhay Charanaravinda (A. C.) with the title “Bhaktivedanta”. In the title, bhakti means “devotion”, and vedanta means “the culmination of Vedic knowledge”.[45] Thus the honorary title acknowledged his scholarship and devotion.[3]

In an effort to fulfill the order of his guru, in 1944 A. C. Bhaktivedanta began publishing Back to Godhead, an English fortnightly magazine presenting the teachings of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu.[40][46][47] He singlehandedly wrote, edited, financed, published, and distributed the magazine,[48][49] today still published and distributed by his followers.[50][51]

In 1950 A. C. Bhaktivedanta accepted the vanaprastha ashram (the traditional retired order of life), and went to live in Vrindavan, regarded as the site of Krishna’s Lila (divine pastimes),[32] although continuing to commute to Delhi on occasion.[52] In Mathura, adjoining Vrindavan, he wrote for and edited the Gauḍīya Patrikā magazine published by his godbrother[b] Bhakti Prajnan Keshava.[53]

In 1952, A. C. Bhaktivedanta attempted to set up organized spiritual activities in the central Indian city of Jhansi, where he started “The League of Devotees”[54][55] — only to see the organization collapse two years later.[47][56]

On September 17, 1959,[52] prompted by a dream of Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati calling on him to accept sannyasa (renounced order of life), A. C. Bhaktivedanta formally entered sannyasa asrama from Bhakti Prajnan Keshava at his Keshavaji Gaudiya Math in Mathura and was given the name Bhaktivedanta Swami. Wishing to preserve the initiatory name given him by Bhaktisiddhanta, as a sign of humility and connection to his spiritual master he kept the initials “A. C”. before his sannyasa name. Now he was A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami.[57]

From 1962 to 1965 Bhaktivedanta Swami stayed in Vrindavan at the Radha-Damodar temple. There he began the task of translating from Sanskrit into English and commenting on the eighteen-thousand-verse Srimad-Bhagavatam (Bhagavata Purana), [58] the foundational text of Gaudiya Vaishnavism.[59] With great effort and struggle, he finally succeeded to translate, produce, raise funds for, and print the first of its twelve cantos, in three volumes.[60]

After accepting sannyasa, Bhaktivedanta Swami began planning to travel to America to fulfill his spiritual master’s desire to spread Chaitanya’s teachings in the West.[62][63]

To leave India, Bhaktivedanta Swami had many hurdles to overcome: He needed a sponsor in America, official approvals in India, and a ticket for his travel. After significant difficulties he managed to secure the needed sponsorship and approvals,[58] he approached one of his well-wishers, Sumati Morarjee, the head of the Scindia Steam Navigation Company, to ask for free passage to America on one of her cargo ships.[64] Because of his age, she at first tried to dissuade him.[52][65] Finally she relented and granted him a ticket on a freighter, the Jaladuta. Bhaktivedanta Swami began the 35-day journey to America on August 13, 1965, at the age of 69.[66][67]

Bhaktivedanta took with him little more than a suitcase, an umbrella, some dry cereal, forty Indian rupees (about seven US dollars), and two hundred three-volume sets of his translation of the first canto of Srimad-Bhagavatam.[68][69][70][71]

After surviving two heart attacks during his maritime journey,[72] Bhaktivedanta Swami finally arrived at the Boston Harbor on September 17, 1965, and then continued on to New York City.[73]

Bhaktivedanta Swami had no support or acquaintances in the United States except the Agarwals, an Indian-American family, who, although strangers to him, had agreed to sponsor his visa.[63][c] Upon reaching New York, he took a bus to the town of Butler, Pennsylvania, where the Agarwals lived. In Butler he delivered lectures to different groups at venues like the local YMCA.[75][76]

After a month in Butler, he returned by bus to New York City.[63] He stayed at various places — sometimes in a windowless room,[77] sometimes a Bowery loft[78] — until with the help of early followers he found a place to stay in the Lower East Side, where he converted a storefront curiosity shop with the serendipitous name “Matchless Gifts” into a small temple[79][80] at 26 Second Avenue.[79][81][82][83][84] There he offered classes on the Bhagavad-gita and other Vaishnava texts and held kirtan (group chanting) of the Hare Krishna mantra:

Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare

Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare.[85]

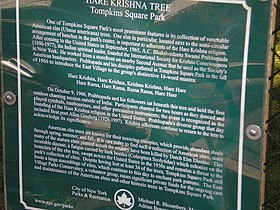

After he and his followers held Hare Krishna kirtan one Sunday under a tree in nearby Tompkins Square Park, The New York Times reported the event: “Swami’s Flock Chants in Park to Find Ecstasy; 50 Followers Clap and Sway to Hypnotic Music at East Side Ceremony”.[86] He slowly gained a following, mainly from young people of the 60s counterculture.[79]

In contrast to the 60s countercultural lifestyle, he required that in order to receive spiritual initiation his followers had to vow to follow four “regulative principles”: no illicit sex (that is, sex outside of marriage), no eating of meat, fish, or eggs, no intoxicants (including drugs, alcohol, cigarettes, and even coffee and tea), and no gambling.[87][88] New initiates also vowed to daily chant sixteen meditative “rounds” of the Hare Krishna 'mantra' (that is, to complete sixteen circuits of chanting the mantra on a 108-bead strand). During the first year in New York, he initiated nineteen people.[79]

In July 1966 he incorporated the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON).[82][79][89][90][d]

In December of 1966 he made a recording of Krishna kirtan (along with a brief explanatory talk) that took the form of an album entitled Krishna Consciousness,[92] released under the “Happening” record label. The record helped the early spread of what he called “the Hare Krishna movement”. [93][94]

With his small band of followers in a little storefront, he was already sharing a vision of spreading “Krishna consciousness” around the world. He asked them to help — for example, by typing his manuscripts for the second canto of the Srimad-Bhagavatam.[95] After he completed his Bhagavad-gita As It Is (by mid January of 1967),[96] he asked a new disciple to find a publisher for it.[97]

Bhaktivedanta Swami personally taught his first followers to spread Krishna’s message, prepare food to offer to Krishna, collect donations, and chant the Hare Krishna maha-mantra (“great mantra”) on the streets.[98]

|

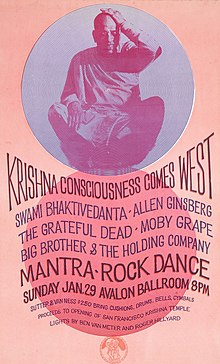

Main article: Mantra Rock Dance |

In 1967 Bhaktivedanta Swami established a second center, in San Francisco.[7][99][100] The opening of the temple in the heart of the booming hippie community of Haight-Ashbury attracted many new adherents and was a turning point in his movement’s history, marking the beginning of rapid growth.[79][101] To gain attention and raise funds, his disciples organized a two-hour concert with kirtan led by Bhaktivedanta Swami and rock performances by the Grateful Dead and other famous rock groups of the day.[102] This “Mantra Rock Dance”, held at the popular Avalon Ballroom, attracted some three thousand people[102] and brought attention to the local Hare Krishna temple. One commentator dubbed it the “ultimate high of that era”.[103]

Later that year, Bhaktivedanta Swami’s followers organized San Francisco’s first Ratha Yatra, the festival he had celebrated as a child in imitation of the massive parade held annually in the Indian city of Puri. For this first San Francisco version, a flatbed truck with four pillars holding a canopy took the place of Puri’s three huge ornate wooden vehicles.[104] He would later establish this annual festival in major cities around the world,[105] with big vehicles —“chariots” — and thousands of people taking part.

At first Bhaktivedanta Swami’s followers referred to him as “the Swami”[106] or “Swamiji”.[79] From mid-1968 onwards they called him “Prabhupada”, a respectful epithet that “enjoys currency with devotees and an increasing number of scholars”.[3]

In 1968, Prabhupada asked three married couples among his disciples to open a temple in London, England. Following his instructions, the disciples, dressed in their robes and saris, began singing Hare Krishna regularly on London streets and at once attracted attention. Soon newspapers carried headlines like “Krishna Chant Startles London” and “Happiness is Hare Krishna”.[107]

A further breakthrough came in December 1969 when the disciples managed to meet with members of the rock band the Beatles, who were at the peak of their global fame.[108][107] Even before then, George Harrison and John Lennon had gotten a copy of the maha-mantra recording released by Prabhupada and his students in New York and had begun singing Hare Krishna.[94][109]

In August 1969, Harrison produced a single of the Hare Krishna mantra, sung by the London disciples, and released it on Apple Records.[108][107][109] For the recording, the disciples called themselves “The Radha Krishna Temple”.[110] Harrison told a press conference convened by Apple that the Hare Krishna mantra was not a pop song but an ancient mantra that awakened spiritual bliss in the hearts of people listening to and repeating it.[111] Seventy thousand copies of the record sold on the first day.[107] It rose to number 11 on the British charts,[109] and Prabhupada’s students performed live four times on the BBC’s popular TV show Top of the Pops.[112] The record was also a success in Germany, Holland, France, Sweden, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia (as well as South Africa and Japan), and so the group was invited to perform in a number of European countries.[113]The next year, 1970, Harrison produced with Prabhupada’s disciples another hit single, “Govinda”, and in May 1971 the album The Radha Krishna Temple.[108][109] In 1970, Harrison sponsored the publishing of the first volume of Prabhupada’s book Kṛṣṇa, the Supreme Personality of Godhead,[107][114] which relates the activities of Krishna's life as told in the tenth canto of the Srimad-Bhagavatam. In 1973 Harrison donated a seventeen-acre estate known as Piggots Manor,[115] fifteen miles northwest of London. The Hare Krishna devotees converted this into a rural temple-ashram and renamed it Bhaktivedanta Manor[116] in Prabhupada’s honor.

Once Prabhupada’s disciples had made a start in England, Prabhupada over the years visited England many times and from there traveled to Germany, France, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, and the Netherlands,[117] leading kirtans, installing forms of Krishna in ISKCON temples, meeting religious and intellectual leaders and others keen to meet him, and guiding and encouraging his disciples.[e]

In 1970 Prabhupada made the first of several visits to Kenya.[117] Although the disciples he had sent there had settled into doing spiritual programs for the local Indian people, Prabhupada insisted on doing programs meant for Africans. On one notable occasion in Nairobi, when he was scheduled to do a program at an Indian Radha-Krishna temple in a mainly African area downtown, he ordered the doors opened to invite the local residents, so that the hall soon flooded with African people.[118] Then he held kirtan and gave a talk. Prabhupada told his local leaders that this is what they should do: spread Krishna consciousness among the local African people.[119] Prabhupada also later visited Mauritius and South Africa[117] and sent his disciples to Nigeria and Zambia.[120]

Prabhupada’s visit to Moscow from June 20 to June 25, 1971 marked the beginning of Krishna consciousness in the Soviet Union.[121] During his five days in Moscow, Prabhupada managed to meet only two Soviet citizens: Grigory Kotovsky, a professor of Indian and South Asian studies, and Anatoly Pinyaev, a twenty-three-year-old Muscovite.[f] Pinyaev, who went on to become the first Soviet Hare Krishna devotee, met Prabhupada through the son of an Indian diplomat stationed in Moscow.[122] Prabhupada’s assistant gave Pinyaev a copy of Prabhupada’s Bhagavad-gita, which Pinyaev was able to translate into Russian, copy, and then distribute underground in the Soviet Union during Communist times.[123] Pinyaev showed a great interest in Gaudiya Vaishnavism, accepted initiation from Prabhupada, and did much to ignite interest in Krishna consciousness in the Soviet Union.[121] Pinyaev was later imprisoned in Smolensk Special Psychiatric Hospital and forcibly treated with drugs for his practice of Krishna consciousness.[121][124]

Having achieved some success in the West, in 1970 Prabhupada directed his attention especially to India, with the hope of turning India back toward her original spiritual sensibilities.[125] He came back to India with a party of Western disciples[62] — ten American sannyasis and twenty other devotees[107] — and for the next seven years focused much of his effort on establishing temples in Bombay, Vrindavan, Hyderabad, and a planned international headquarters in Mayapur, West Bengal (the birthplace of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu).[62]

By that time, Prabhupada saw, India had set a course towards Europeanization[72] and sought to imitate the West. Therefore, the appearance on Indian soil of American and European Hare Krishna devotees who had rejected Western materialism and embraced Indian spiritual culture “caused nothing less than a sensation among the modernizing (i.e. Westernizing) Indians, planting seeds for an authentic religious revival there”.[126]

By the early 1970s, Prabhupada had established his movement’s American headquarters in Los Angeles and its world headquarters in Mayapur.[127]

In Latin America, Prabhupada visited Mexico and Venezuela. In Asia he visited Hong Kong, Japan, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines. He also spent time in Australia, New Zealand, and Fiji. In the Middle East he visited Iran.[117] Among the places he sent disciples to spread Krishna consciousness was China.[120]

Early in the movement, Prabhupada had guided his students personally, but later, as the movement rapidly expanded, he relied more on letters and his secretaries.[128] By giving his students instructions, advice, and encouragement, he ensured a “strong paternal presence” in their lives.[98] He wrote more than six thousand letters, many now collected and kept at the Bhaktivedanta Archives.[129] Besides receiving reports of accomplishments, via correspondence he also had to deal — almost daily — with setbacks, perplexities, quarrels, and failures. He tried to correct them as much as possible and kept on advancing his movement.[129]

Wherever he was, he took an hour-long early-morning walk, which became a time for disciples to ask questions and receive personal guidance.[130] On returning from his walk, he lectured daily on the Srimad-Bhagavatam,[131] often reading from the portion of the manuscript he was working on. Every afternoon he met with disciples or with dignitaries and leaders from various parts of his mission.

Traveling constantly to lecture and tend to his disciples, Prabhupada circled the world fourteen times in ten years.[132] He opened more than one hundred temples and dozens of farm communities and restaurants, as well as gurukulas (boarding schools) for ISKCON's children.[133] He initiated nearly five thousand disciples.[134]

On November 14, 1977, at the age of 81, after a long illness,[g] Prabhupada passed away in his room at the Krishna Balaram Mandir,[2][136] the temple he had established in Vrindavan, India.[137][138][139] His burial site is located in the courtyard of the temple beneath a samadhi (memorial shrine) built by his followers.[2][140]

In 1970 Prabhupada established a Governing Body Commission (GBC), then consisting of twelve leading disciples, to oversee ISKCON’s activities around the world and to serve as ISKCON’s ultimate managing authority.[139] In 1977, four months before his death, he appointed eleven senior disciples to perform spiritual initiations on his behalf while he was ill.[141]

Despite the measures Prabhupada took to organize the management of his movement, his death caused a crisis of authority in ISKCON that destabilized the organization and became a turning point in its development.[138][142][143] The succession process was beset by conflicts, with disagreements persisting for decades.[144][145] Nonetheless, by 2023 nearly one hundred disciples and grand-disciples in succession from Prabhupada were serving as initiating gurus in his branch of the Gaudiya Vaishnava lineage.[146]

Within Eastern systems, spiritual lineages are integral to each tradition, and a teacher is mandated to maintain theological fidelity by transmitting knowledge as given in the lineage.[147] Prabhupada comes in the Brahma-Madhva-Gaudiya lineage, which traces back to the saint and mystic Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486–1533)[148] and the theologian Madhvacharya (1238–1317), and further back, its teachings say, to the beginnings of creation.[149] This lineage (sampradaya) follows such texts as Srimad-Bhagavatam, the Bhagavad-gita, and the writings of Chaitanya’s disciples and their followers.[150] Prabhupada’s extensive commentaries on the sacred texts follow those of Bhaktisiddhanta, Bhaktivinoda, and other traditional teachers, such as Baladeva Vidyabhushana, Vishvanatha Chakravarti, Jiva Goswami, Madhvacharya, and Ramanujacharya.[151][152]

In accordance with the teachings of the Srimad-Bhagavatam, Prabhupada taught that the supreme truth, or Absolute Truth, is the one unlimited, undivided spiritual entity that is the source of all. That Absolute Truth, he taught, is realized in three phases: as Brahman (all-pervading impersonal oneness), as Paramatma (the aspect of God present within the heart of every living being), and as Bhagavan, the Supreme Personality of Godhead. Though the Absolute Truth is one, he taught, that one Absolute is progressively realized in these three features according to one’s level of spiritual advancement. In the initial stage the Absolute is realized as Brahman, in a more advanced stage as Paramatma, and at the most advanced stage as Bhagavan.[153][154][155][156]

In the Srimad-Bhagavatam, and so in Prabhupada’s teachings, Krishna is seen as the original and supreme manifestation of Bhagavan[149] – in Sanskrit, svayam-bhagavan, or the Supreme Personality of Godhead himself.[157] No one is equal to or greater than Krishna.[158] Brahman and Paramatma are partial realizations of Krishna.[158] The various Vishnu forms, such as Rama and Narasimha, are “nondifferent” from Krishna; they are the same Personality of Godhead, appearing in different roles. The form of Krishna is the original and the most complete form. In the Hindu pantheon, he taught, the gods other than the Vishnu forms are demigods — that is, assistants of the Supreme Personality of Godhead.[153]

If the Absolute Truth is one, this raises the question of how there can be diversity. If, as the Upanishads say, there is only the Absolute Truth and nothing else, we need some way to account for the existence of living beings, with all their differences, and the world, with all its many colors, forms, sounds, aromas, and so on. Prabhupada responds by referencing a statement from the Upanishads that the Absolute Truth has varied energies.[159][160] As a fire located in one place gives off heat and light throughout a room, the Absolute Truth fills the world with every sort of variety.[161]

Prabhupada taught Chaitanya’s doctrine of achintya bheda-abheda-tattva, in which everything is seen as simultaneously, inconceivably one with the Absolute — that is, with Krishna — and yet different.[159][162][163] By way of analogy, Prabhupada gives the example that heat is in one sense identical with the fire from which it emerges and yet the two are different — when sitting in a fire’s warmth, we are not burning in the fire itself.[161][164] This “oneness and difference” accounts for the oneness of an Absolute Truth that includes limitless varieties.[159][162][163]

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

Among Krishna’s energies, Prabhupada taught, the ingredients of this world collectively belong to Krishna’s “inferior energy”[165] — inferior in that, being inert matter, it lacks consciousness.[166][167] But superior to inert matter are the conscious living beings (jivas) that belong to Krishna’s “superior energy”.[168][169]

Because the living beings belong to Krishna’s “superior energy”, Prabhupada taught, they share in Krishna’s divine qualities, including knowledge, bliss, and eternality (sat, cit, and ananda).[166][169] But because of contact with the “inferior energy” since time immemorial,[170] the divine nature of the living beings has been covered, and subjecting the living beings in this world to ignorance, suffering, and repeated birth and death.[171] In each life the living beings struggle against birth and death, disease and old age.[172] While trying to control and enjoy the resources of nature, the living beings increasingly suffer from entanglement in nature’s complexities.[173]

As spiritual beings, belonging to the “superior energy”, the living beings are different from their material bodies: the body may be male or female, young or old, white or black, American or Indian, but the living being within the body is beyond what he called these “material designations”.[174] Prabhupada phrased this understanding in a maxim he often used: “I am not this body”.[175][176]

When we falsely identify with these bodies, he taught, we are under the influence of maya, or illusion. Only when this illusion is dispelled can the soul become liberated from material existence.[172]

Prabhupada taught that the living beings can be freed from illusion, and from their entire material predicament, by recognizing that they are tiny but eternal parts of Krishna and that their natural engagement lies in serving Krishna, just as a hand serves the body. Dormant within every living being, Prabhupada taught, is an eternal loving relationship with that Absolute, or Krishna, and when that loving relationship is revived, the living being resumes its natural eternal and joyful life.[177] This eternal service in devotion to Krishna, rendered by one freed from all material designation, is called bhakti.[158]

One can begin practicing bhakti, Prabhupada taught, even while in the earliest stages of spiritual life. In this way, bhakti is both the final end to be achieved and the means by which to achieve it. As a spiritual practice, bhakti is a powerful, transformative process that purifies the soul and enables it to see God directly.[172]

Prabhupada crusaded against what he called “impersonalism” — that is, the idea that ultimately the Supreme has no form, qualities, activities, or personal attributes. In this way he stood opposed to the teachings of Shankara (A.D. 788–820), who held that everything except Brahman is illusory, including the soul, the world, and God.[178] Before Prabhupada, Shankara’s system of thought, known as Advaita Vedanta, had generally provided the framework for Western understandings of Hinduism,[179] and the “steady procession of Hindu swamis” who came to America generally aligned themselves with Shankara’s monistic views and the idea of “the ultimate absorption of the self into an impersonal Reality or Brahman”.[180]

But prominent Vaishnava philosophers from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries like Madhva and Ramanuja had opposed Shankara’s views with personalistic understandings of Vedanta. Those teachers presented strong philosophical arguments criticizing Shankara’s “illusionism” (mayavada), his view that personal individuality, indeed all individuality, is illusory.[178][181] Philosophers in the Gaudiya line such as, in the sixteenth century, Jiva Goswami had continued to argue formidably against impersonalism, which they regarded as the essential metaphysical misconception”.[182] So Prabhupada strongly opposed impersonalistic views wherever he encountered them and asserted the eternal personal existence of the Absolute and of all living beings.[178] Where Buddhism shares ground with Shankara’s views by teaching that ultimately personality disintegrates, leaving nothing but a void nirvana,[183] Buddhism too came in for Prabhupada’s strong personalistic critique.[183][184]

Prabhupada taught that society should ideally be organized in such a way that people have specific duties according to their occupation (varna) and stage of life (ashrama).[185] The four varnas are intellectual work; administrative and military work; agriculture and business; and ordinary labor and assistance. The four ashramas are student life, married life, retired life, and renounced life. In accordance with the Bhagavad-gita and in opposition to the modern Hindu caste system, Prabhupada taught that one’s varna, or occupational standing, should be understood in terms of one’s qualities and the work one actually does, not by one’s birth.[186]

Moreover, devotional qualifications always supersede material ones.[187] Following Chaitanya, who challenged the caste system and undercut hierarchical power structures,[188] Prabhupada taught that anyone could take to the practice of bhakti-yoga and become self-realized through the chanting of God’s holy names, as found in the Hare Krishna maha-mantra.[172]

Prabhupada also emphasized the importance of self-sufficient farming communities as places where one could live simply and cultivate Krishna consciousness.[189]

The main spiritual practice Prabhupada taught was Krishna sankirtana (also simply called kirtan or kirtana), in which people musically chant together names of Krishna, especially in the form of the maha-mantra:

Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare

Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare.

Kirtan literally means “description”, hence “praise”, and sankirtana indicates kirtan performed by people together.[190]

On the authority of traditional Sanskrit texts, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu had taught that Krishna kirtan is the most effective method for spiritual realization in the present age (Kali-yuga) – more effective than silent meditation (dhyana), speculative study (jnana), worship in temples (puja), or performing the various physical or mental disciplines of yoga. Krishna kirtan, he had taught, can be done by anyone, anywhere, at any time, and without hard-and-fast rules. Because the names of Krishna are “transcendental sounds”, identical with Krishna himself, the chanting is spiritually uplifting.[191]

When Prabhupada began his efforts to spread Krishna consciousness in the United States, he held kirtans in a Bowery loft, in his early storefront temples, in Tompkins Square Park in New York and Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, and wherever else he went.[192] Following Prabhupada, his disciples soon began holding kirtans regularly in streets, parks, temples, and other venues in major cities in North America and Europe and then in Latin America, Australia, Africa, and Asia.Because of Hare Krishna kirtan, Prabhupada’s movement itself came to be referred to simply as “Hare Krishna” and its followers as “Hare Krishnas”.[h]

Theologically speaking, the term sankirtana can extend from the public chanting of Hare Krishna to the distribution of books spoken by or about Krishna. Kirtan in the sense of public chanting is traditionally accompanied by kartals (hand cymbals) and mridangas (drums), and Prabhupada’s spiritual master and grand spiritual master had said that distribution of Krishna literature was the “great mridanga” because such distribution spreads Krishna consciousness still further.[128][193][194] Prabhupada therefore gave great importance to such distribution.

Prabhupada’s tradition constantly makes the point that “association with saints inspires saintliness, association with devotees inspires devotion. The association of genuine devotees can exert a powerful effect upon one's consciousness”.[195] And so when Prabhupada incorporated ISKCON, its founding document included as one the Society’s purposes “To bring the members of the Society together with each other and nearer to Krishna”.[196]

Prabhupada required of his followers, as a prerequisite for spiritual initiation, that they promise to follow four “regulative principles”: no illicit sex (that is, no sex outside of marriage), no eating of meat, fish, or eggs, no intoxicants (including drugs, alcohol, cigarettes, and even coffee and tea), and no gambling.[88][197] New initiates also vowed to daily chant sixteen meditative “rounds” of the Hare Krishna mantra (that is, to complete sixteen circuits of chanting the mantra on a 108-bead strand).[88]

For at least the last millennium, the Srimad-Bhagavatam has been “by far the most important work in the Krishna tradition” and “the scripture par excellence of the Krishnaite schools”.[198] It is sometimes described as “the ripened fruit of the Vedic tree”.[45][199] Accordingly, Prabhupada instituted daily classes on the Bhagavatam in all his centers,[200] and he spoke on Bhagavatam daily, wherever he went.[201]

In accordance with Vaishnava teachings, Prabhupada introduced worship of Krishna in the form of a murti: figures cast in metal or carved in stone or wood to match descriptions of Krishna given in Vaishnava texts. Scholar of religion Kenneth Valpey writes:

“Prabhupāda explained that although omnipresent, Kṛṣṇa makes himself perceivable and hence worshipable through material elements which are, after all, his own ‘energies.’ Based on this reasoning one should understand the image of Kṛṣṇa to be ‘Kṛṣṇa personally,’ appearing in a way quite suitable for our vision,’ that is, perceivable by ordinary persons with ordinary powers of sight”.[202]

Prabhupada taught that because Krishna is personally present as the deity (the term Prabhupada used for such a form), worshiping the deity helps one develop loving exchanges with Krishna. Prabhupada installed deities in ISKCON temples around the world.[203]

Food prepared and offered to the deity of Krishna with devotion becomes sanctified as krishna-prasadam ("mercy of Krishna"). Prabhupada taught that eating only prasadam purifies one’s existence and helps one develop in bhakti.[204] From the beginning of his mission Prabhupada distributed prasadam to visitors[205][206] and soon made it into the movement's major outreach vehicle.[207][208] A weekly prasadam feast for the public has always been a program at all of ISKCON centers.[209][210] Prabhupada wrote, “The Hare Krishna Movement is based on the principle: chant Hare Krishna mantra at every moment, both inside and outside of the temples, and, as far as possible, distribute prasadam".[211]

Prabhupada’s predecessors such as Rupa Goswami had taught the value of living in Vrindavan (sometimes spelled “Vrindaban”), the sacred town between Agra and New Delhi that is held to be the site of Krishna’s rural “pastimes” on earth and therefore conducive to constant remembrance of Krishna. Prabhupada accordingly brought his disciples on pilgrimage to Vrindavan and there established the Krishna-Balaram temple. Yet with a broader outlook he wrote one disciple, “[W]herever you remain, if you are fully absorbed in your transcendental work in Krishna consciousness, that place is eternally Vrindaban. It is the consciousness that creates Vrindaban”.[212]

Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, who had specifically encouraged writing and publishing, at one meeting told Prabhupada: If you ever get money, print books.[18][213] So regardless of how busy or sometimes unwell Prabhupada might have been, he remained focused on producing books.[214] Prabhupada slept little, waking at 1:00 am every night[215] to translate and comment on the Srimad-Bhagavatam and other texts.[216] During the day he would give attention to guiding disciples and seeing to the affairs of his international society and its temples, and very early in the morning, while most people were asleep, he did most of his writing “because even with his age and uncertain health, he was unwilling to sacrifice his writing time for extra rest”.[217]

By 1970 he had translated the Bhagavad-gita, two cantos of the Bhagavatam, a summary study of its tenth canto, and a summary volume drawn from the expansive Caitanya-caritamrta. From 1970 on, his literary output slowed only slightly due to the demands of his expanding Hare Krishna movement.[218] His task, as scholars have observed, was not merely to translate the text but to translate an entire tradition.[219][220]

Historian of religion Thomas Hopkins relates that Prabhupada told him in a conversation in Philadelphia in 1975 that "the Gita provided the basic education on Krishna devotion, the Srimad-Bhagavatam was like graduate study, and the Caitanya-caritamrita was like postgraduate education for the most advanced devotees”.[221]

Hopkins says that by presenting in English such works as the Bhagavatam and Caitanya-caritamrta, Prabhupada made important texts accessible to the Western world that were simply not accessible before. Hopkins says, “[W]hat few English translations there were of the Bhagavata Purana and Caitanya-caritamrta were barely adequate and very hard to get hold of”.[220][i] Prabhupada, Hopkins says, “made these and other texts available in a way that they never were before” and “made the tradition itself accessible to the West”.[220]

In 1966-67, Prabhupada wrote a translation and commentary on the Bhagavad-gita he entitled Bhagavad-gita As It Is. It was first published by the Macmillan Company in 1968 in an abridged edition and later, in 1972, in full.[222] For each verse he first gives the Sanskrit Devanagari script, then a roman transliteration and word-for-word gloss, followed by his translation and a commentary, or “purport”.[223] Scholar of religion Richard H. Davis comments that this was “the first English translation of the Gita to supply an authentic interpretation from an Indian devotional tradition”.[224] It is “by far the most widely distributed of all English Gita translations”.[223] In 2015 Davis wrote, “The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust estimates that twenty-three million copies of Prabhupada’s translation have been sold, including the English original and secondary translations into fifty-six other languages”.[224] For Prabhupada, Davis says, “the essential fact about the Bhagavad-gita is its speaker. The Gita contains the words of Krishna, and Krishna is the ‘Supreme Personality of Godhead.’” In Prabhupada’s view, other translations lack authority because the translators use them to express their own opinions rather than the message of Krishna. In contrast, Prabhupada saw his task in presenting what Krishna wanted to say, and so he claimed to present the Bhagavad-gita “as it is”.[225]

At once a sacred history, a theological treatise, and a philosophical text,[226] the Srimad-Bhagavatam “stands out by reason of its literary excellence, the organization that it brings to its vast material, and the effect that it has had on later writers”.[227] Praising the poetry of the Bhagavatam, scholar of religion Edwin Bryant says, “[S]cholars of the text have every right to say that ‘the Bhagavata can be ranked with the best of the literary works produced by mankind.’”[228]

It was this great work that Prabhupada, after taking sannyasa, set out to present in English, with, once again, the original Sanskrit text, its word-for-word meanings, a translation, and an in-depth commentary.[229] Also known as Srimad-Bhagavata Purana, Bhagavata Purana, or just the Bhagavata[230] Srimad-Bhagavatam is a work of twelve books (“cantos” was the word Prabhupada used) comprising more than fourteen thousand verse couplets.[231] “Srimad” means “beautiful” or “glorious”.[232]

Prabhupada began his translation and commentary on the Bhagavatam after accepting sannyasa in 1959, and by 1965 he had completed and published the first canto.[233] He worked on translating the Srimad-Bhagavatam into English for the rest of his life.[217]

The cantos were published one by one, as he finished them. He completed nine cantos and thirteen chapters of the tenth. The rest of the Bhagavatam was completed by his disciples.[217]

Considering his old age and the vast size of the Bhagavatam, Prabhupada knew he might not live to finish it. So in 1968 he undertook to present the Bhagavatam’s tenth canto — the essence of the work — in summary form as Krsna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead.[234]

This summary study is “Prabhupada’s own exposition of the story of Krishna as it is told in the Tenth Canto”.[217] It “laid out the account of Krishna from the Bhagavata Purana that provides the images and stories central to Krishna devotion”.[235]

As Bryant says:

“The tenth book of the Bhāgavata has inspired generations of artists, dramatists, musicians, poets, singers, writers, dancers, sculptors, architects and temple-patrons across the centuries. Its stories are well known to every Hindu household across the length and breadth of the Indian subcontinent, and celebrated in regional festivals all year round”.[236]

Prabhupada himself inspired artists among his disciples to provide the text with profuse full-color illustrations. Such illustrations became a feature of nearly all his books.[237]

A related work is Light of the Bhagavat, written by Prabhupada in Vrindavan in 1961, before he went to the West, but published only after his death. The book is a treatment of one chapter (chapter twenty) of the tenth canto. Prabhupada composed forty-eight commentaries for the chapter’s verses. The book is accordingly illustrated with forty-eight paintings.[238]

In 1969 Prabhupada published, again in his full verse-by-verse format, his translation and commentary for the Ishopanishad[239] — also known as the Īśa Upaniṣad or Īśāvāsya Upaniṣad,[240] which in 1960 he had partially serialized in his Back to Godhead magazine.[239] The Ishopanishad, consisting of only eighteen mantras,[241] is considered one of the principal Upanishads.[242] In all indigenous collections of the Upanishads, the Iśopaniṣad comes first.[240] Its first verse, “highly regarded as a capsule of Vedic theology”,[45] presents a god-centered view of the universe.[239] The celebrated traditional commentator Shankara wrote, “One who is eager to rid himself of the suffering and delusion of saṁsāra, created by ignorance, and attain Supreme Bliss is entitled to read this Upaniṣad”.[243]

Begun in 1968,[244] The Nectar of Devotion is a summary study of Rupa Goswami’s Bhakti-rasamrita-sindhu, his “famous exposition of the principles of devotion”.[244] Scholar-practitioner Shrivatsa Goswami has described Bhakti-rasamrita-sindhu as “a textbook of devotional practice, an exposition on the philosophy of devotion, and a study of devotional psychology”.[245] The Nectar of Devotion “gave access to Gaudiya Vaisnavism’s most important theological treatise on devotion”.[235]

Caitanya-caritamrta is the seventeenth-century account of the life and teachings of Chaitanya, who founded the Gaudiya Vaishnava tradition.[244] Written in the Bengali language, it runs to more than 15,000 verses and “is regarded as the most authoritative work on Śrī Caitanya”, a work of “rare merit”, with “no parallel in the whole of Bengali literature”.[246] Scholar of religion Hugh Urban calls it “one of the greatest works in all of Indian vernacular literature”.[247]

Prabhupada completed his translation in 1974, within two years,[218] and it was published in seventeen volumes, again with verse-by-verse text, transliteration, word meanings, translation and commentary.[229] He based his commentary on the Bengali commentaries of his predecessors Bhaktivinoda Thakura and Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati.[151]

Before Srila Prabhupada’s translation, the work in English was simply unavailable. After Prabhupada’s edition came out, scholar J. Bruce Long wrote, “The appearance of an English translation of Kṛṣṇadāsa Kavirāja Gosvāmī's Śri Caitanya-caritāmṛta by A. C. Bhaktivedānta, Founder-Ācārya of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, is a cause for celebration among both scholars in Indian Studies and lay-people seeking to enrich their knowledge of Indian spirituality”.[248]

Several years earlier, in 1968, Prabhupada published Teachings of Lord Caitanya.[249] The book offers a summary of selected portions of Caitanya-caritamrita.[250] [j]

Prabhupada also wrote a verse-by-verse commentated translation of Rupa Goswami’s eleven-verse Upadeshamrita,[239] one of Rupa Goswami’s shortest works,[251] which provides concise directions on how to carry out devotional service.[147]

In 1972 Prabhupada founded the Bhaktivedanta Book Trust (BBT), which manages the international publishing and distribution of his writings.[62][90][252] Apart from his major works, the BBT publishes various paperbacks derived from his lectures.[232] The BBT also publishes Back to Godhead, the magazine Prabhupada founded, in multiple languages.[253] Between 1973 and 1977, Prabhupada’s followers distributed several million books and other pieces of Krishna conscious literature every year in shopping malls, airports, and other public locations in the United States and worldwide.[254] As of 2023, his books had been translated into eighty-seven languages.[255] In 2022, the BBT printed more than two million pieces of literature.[256]

Shrivatsa Goswami has said, “Making these Vaiṣṇava texts available is one of Śrīla Prabhupāda’s greatest contributions. Apart from the masses, his books have also reached well into academic circles and have spurred academic interest in the Caitanya tradition”.[257] Further, he says, “The significance of making these texts available is not merely academic or cultural; it is spiritual. Jñāna, knowledge, is spread, proper doctrines are made known, people come closer to reality”.[257] Other academics, too, have applauded Prabhupada’s publications[258] as his most significant legacy.[259]

But his edition of Bhagavad-gita, in particular, has come in for criticism as well. Eric Sharpe, scholar of religion, considers Prabhupada’s reading of Bhagavad-gita single-minded and fundamentalist.[260] Sanskrit scholar A.L. Herman concurs.[261] Another scholar, K. P. Sinha, takes exception to Prabhupada’s “misinterpretations and unkind remarks” directed toward Advaita Vedanta, the philosophy of absolute monism.[262][k]

The most detailed critical analysis by a Western, non-Hindu scholar comes from historian of religion Robert D. Baird.[260] Baird takes upon himself the task of not merely seeing Prabhupada as “an authentic proponent of Vaishnavism” but of examining as an academic scholar the way Prabhupada reads the Bhagavad-gita.[263]

Whereas many scholars, Baird writes, see “some degree of progression” in the Gita, with different themes emphasized in different parts of the book, Prabhupada “reads the complete teaching of the book, indeed of Vedic literature generally, into any passage”.[264] It appears “that he considers it legitimate to interpret any verse in the light of the whole system found in the Gītā whether it is explicitly mentioned in that verse of the Gītā or not”.[265] In this way, he reads “Krishna consciousness” even into portions of the text where Krishna is not explicitly mentioned.[266] Prabhupada cites later passages in the Gita to explain earlier passages.[267] Indeed, he even quotes from other texts in the canon (whether written before the Gita or after[267]) to indicate the intention of the Gita, “as though they have the same authority as the Gita itself”.[267] And so: “In all, a wide range of texts are used to serve as authorities for understanding the Gītā. Swami Bhaktivedanta not only treats specific texts in a way that would be unusual among Western scholars, but he sees specific texts in the light of the Vedas in general”.[268]

Whereas other scholars, Baird writes, would give great attention to the overall structure of the Gita, Prabhupada gives the structure scant notice, preferring instead to make this point: “In every chapter of Bhagavad-gītā, Lord Kṛṣṇa stresses that devotional service unto the Supreme Personality of Godhead is the ultimate goal of life”.[269]

Prabhupada uses the text of the Gita to present various aspects of Krishna theology.[270] And “he also goes beyond specific texts and the Gītā itself when he makes it the occasion for the inculcation of a Vaishnava lifestyle,”[265] typified by chanting the maha-mantra, regulating one’s sexual activity, offering food to Krishna, and following a vegetarian diet.[271] And so: “Swami Bhaktivedanta is more interested in expounding the principles of Krishna consciousness than in merely explicating the text at hand”.[272] In one instance cited, “the text recommends one thing [astanga-yoga] and Bhaktivedanta Swami cancels that and offers the mahāmantra”.[272]

As for competing interpretations: “Bhaktivedanta often seeks to show the superiority of the Vaishnava position and the error of other positions”.[273] “The position that is attacked with the most regularity and vigor is that of Advaita Vedanta,”[273] “the system of thought that is commonly used to provide the structure for Western understandings of ‘Hinduism’”,[179] whose advocates Prabhupada calls Mayavadins, impersonalists, or monists.[273] For Advaita Vedanta he reserves his strongest condemnations.[179]

Nor does Prabhupada only criticize “impersonalists”. Rather, “Scholars in particular come under Swami Bhaktivedanta’s condemnation because they are merely ‘mental speculators’”.[274] In Prabhupada’s view, Baird says, “Since these scholars are not surrendered to Krishna, they are not Krishna conscious; they are merely offering their own ideas rather than the truth within the paramparā system [the lineage of masters and disciples]”.[274] Prabhupada “seldom engages in the kind of argumentation that scholars are accustomed to when deciding between alternative positions”.[275] Instead he takes a position as a spiritual master within the disciplic succession and “merely declares" what is true.[275] And so, Baird says, “The gulf between Swami Bhaktivedanta’s presentation and that of the scholarly exegete is simply unbridgeable, for their purposes operate on different levels”.[263][l]

But what some scholars might see as faults, others see as virtues. Thomas Hopkins sees Prabhupada’s translations and purports as successfully conveying the meaning of the text precisely because Prabhupada draws upon the commentaries of his predecessors and brings to his work the understandings of his entire tradition.[277] Moreover, Hopkins says, Prabhupada does this in such a way that the entire text becomes comprehensible to a modern reader, not only theoretically but practically.[278] Translations of such texts as the Gita, Hopkins says, cannot be done mechanically.[279] The translator has to understand the spirit and the experience that lie behind the text.[279] Where Prabhupada’s translations expand the text, they do so “for the sake of making the meaning more clear, rather than obscuring it”.[280] Hopkins says, “Writing a commentary is not a merely intellectual or academic exercise—it has a practical goal: to engage people with a living spiritual tradition”.[278] Prabhupada, he says, brings the meaning of the text out of the past and into the present, giving it meaning in terms of people’s lives.[151]

In Prabhupada’s efforts to establish and expand Krishna consciousness, some of the difficulties he faced were internal to his new and growing movement. He had to train disciples unaccustomed to Vaishnava culture and philosophy and engage them in furthering his Hare Krishna movement;[281] he had to set up and then guide his Governing Body Commission to see to ISKCON's global management. He often had to intervene when clashes and controversies within ISKCON grew out of hand. He had to sort out difficulties faced by individual disciples, ensure a proper understanding of his teachings, and, more broadly, transplant an entire cultural movement.[282] He also faced challenges from the outside world.

Until the mid-1970s the attitude of the Western public towards Prabhupada and his movement was cordial. News reports tried to reliably describe the Hare Krishna devotees, their beliefs, and their religious practices. The spirit of curiosity prevailed, while hostility was almost nonexistent.[283]

But by the mid-1970s this changed. The rapidly expanding Hare Krishna movement — distinctive, foreign, highly visible, and vigorous (often over-vigorous) in spreading its message — became an early target for a nascent “anti-cult movement”. No longer was the Hare Krishna movement seen to represent an authentic spiritual tradition. Rather, it was now one of a myriad of “destructive cults” that won converts and took over their lives by “mind control” and “brainwashing”. When young adults, supposedly robbed of free will and “programmed” by mind control, became Hare Krishna devotees, some parents hired “deprogrammers” to kidnap them and “free them from the cult”. “Deprogrammings” typically involved days or weeks of isolation, browbeating, and intense verbal haranguing and harassment.[284][285][286][287]

After one such “deprogramming” failed, the New York City District Attorney’s Office charged two local Hare Krishna leaders with illegally imprisoning two Hare Krishna followers by brainwashing them.[288][m]

Prabhupada instructed his disciples to fight these charges, among other ways by entering his books into evidence.[289] Meanwhile, two hundred scholars signed a document defending ISKCON as an authentic Indian missionary movement.[290]

In March of 1977 a New York State Supreme Court justice threw out the charges and recognized that ISKCON represents a bona fide religious tradition.[288] Nonetheless, in America and Europe the “cult” label and image persisted for the rest of Prabhupada’s lifetime and beyond.[291][286]

As scholar James Beckford notes, in the 1970s Hare Krishna devotees became increasingly active in selling their literature and collecting donations from the public,[292] so they were sharply criticized for what was seen as harassing people for money at airports and other public places. As Bryant and Ekstrand comment, “Questionable fund-raising tactics, confrontational attitudes to mainstream authorities, and an isolationist mentality, coupled with the excesses of neophyte proselytizing zeal, brought public disapproval”[133] — something that Prabhupada had to deal with too.

As ISKCON evolved towards being a worldwide organization, it suffered from the inevitable travails of institutionalization. Young disciples, mostly from an anti-establishment, anti-authoritarian background, became members of the GBC and found themselves running a worldwide institution. Preaching sometimes started giving way to revenue production; gender issues arose; leaders sometimes fell, and scandals broke out. Bureaucracy intruded on spontaneity, and many members left. As much as Prabhupada tried to leave management to the GBC, much of this he too had to deal with personally.[133][293]

Prabhupada directed his disciples to train children in boarding schools called gurukulas, where they would receive education from spiritual teachers. However, as reported by sociologist of religion E. Burke Rochford, through mismanagement these schools became like orphanages. After Prabhupada's departure it came to light that physical and sexual abuse occurred within these schools due to lack of oversight.[294]

In India, Prabhupada faced a special set of challenges. He had much to accomplish there, but his American and European disciples were inexperienced in how to get things done in India and even how to live there.[295]

When Prabhupada’s young American followers came to India in the early 1970s and began holding festivals, including public sankirtana, many Indians were surprised to see Westerners adopting Indian modes of worship and devotion. Some local people, including even some Indian officials, suspected that the American devotees must be undercover operatives of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).[296][297]

Outspoken and uncompromising as he was in the way he presented Krishna’s teachings, in India, as elsewhere, Prabhupada found himself battling with opposing views of all sorts.[298] Therefore another challenge came from Prabhupada’s consistent rejection of the common Hindu notion of caste by birth. Since Prabhupada, like his predecessors, insisted that anyone, from any race or nation, could become spiritually purified and fit to perform the duties of priests, he faced opposition from Hindu brahmins who held that performing such duties was an exclusive birthright of their caste.[299][300]

When Prabhupada resolved to build a temple on land in Juhu, Bombay (now Mumbai), the man who had sold ISKCON the land tried to swindle the devotees and take it back. The man had deep political connections in the Bombay municipality and employed lawyers and even thugs to drive the devotees off, but Prabhupada persisted and eventually won.[301][n][non-primary source needed]

While working to establish his movement, Prabhupada had to deal with problems caused even by leading disciples, who, monks or not, could still hold on to intellectual baggage, disdain for authority, and ambitions for power.[302] In 1968 Prabhupada's first sannyasi disciple openly disregarded Prabhupada’s instructions to him and twisted core tenets of Prabhupada’s teachings. This foreshadowed succession problems and issues of authority that Prabhupada’s movement would face both during Prabhupada’s presence and after.[302]

Unlike Indian gurus who declared themselves avatars, divine appearances of God, Prabhupada from the very beginning of his preaching called himself only a servant or representative of God.[303] But in 1970 four of Prabhupada’s early sannyasis announced at a large ISKCON gathering that Prabhupada’s followers had failed to recognize that Prabhupada was actually Krishna, God himself. Prabhupada expelled those sannyasis from his Society (he eventually readmitted them, after they recanted their claim).[302]

In 1972, without consulting Prabhupada, eight of the twelve members of the GBC held a meeting in New York aimed at centralizing control of ISKCON's activities and finances. Their plans would have lessened Prabhupada's own oversight and set aside his emphasis on the autonomy of each ISKCON center. This prompted Prabhupada to suspend the entire GBC "until further notice", establish direct lines of communication with each temple's leaders, and re-emphasize spiritual purity, the selfless and voluntary nature of devotional life, and the exemplary conduct befitting ISKCON leaders. This, he said, is what he wanted, not corporate bureaucracy and excessive centralization. (He later unsuspended the GBC).[302]

In 1975 a clash broke out when a team of ten parties of itinerant sannyasis, assisted by two hundred brahmacharis, criss-crossed America, visiting ISKCON temples to extoll renunciation and a missionary spirit — and urge brahmacharis to abandon the temples and join the sannyasi parties. The temples, the team argued, were led by presidents who were grihasthas (married men), and grihasthas had a propensity for enjoyment that undermined what should be an austere temple atmosphere.[302]

The conflict reached its peak in 1976 in Mayapur at ISKCON’s annual global gathering when a sannyasi-dominated GBC passed resolutions severely restricting the role of women and families in ISKCON.[302] After hearing from both sides, Prabhupada came down against this type of discrimination, calling it “fanaticism”, and had the GBC undo the resolutions. Prabhupada said, "I cannot discriminate — man, woman, child, rich, poor, educated, or foolish. Let them all come, and let them take Krishna consciousness".[302]

In the course of his preaching work in the West, Prabhupada made controversial statements that criticized various ideals of modern society or spoke offensively of certain groups.[304][305][4][o]

"In a traditional Hindu vein”,[6] Prabhupada spoke favorably of the myth of Aryan bloodlines and compared darker races to shudras [people of low caste], thus implying them being inferior to the lighter-complexioned humans.[6] In a recorded room conversation with disciples in 1977, he calls African Americans "uncultured and drunkards", further stating that after being given freedom and equal rights, they caused disturbance in the society.[307]

Prabhupada called democracy "the government of the asses", "nonsense", and "farce", at the same time praising the monarchial form of government and speaking favorably of dictatorship.[308] While comparing Napoleon and Hitler to great demons of Hindu mythology Hiranyakashipu and Kamsa, he called their activities "very great". On other occasions, he made "generally approving remarks about Hitler" and said that Hitler killed the Jews because they "were financing against Germany".[309] He also expressed some misogynistic views, asserting that "women cannot properly utilize freedom and it is better for them to be dependent",[310] stating that they are "generally not very intelligent",[311] and "in general should not be trusted".[311]

Scholars have commented, however, on the contrast between such controversial pronouncements and the full picture of what Prabhupada actually taught and did.[312] Kim Knott, a religious studies scholar, extensively discusses Prabhupada’s statements about women.[313] Describing her perspective in relation to ISKCON as that of an “outsider” and a “western feminist”,[313] she highlights Prabhupada's firm belief that "bhakti-yoga", the path of Krishna Consciousness, allows transcendence beyond gender distinctions.[314] Knott emphasizes that, according to Prabhupada, women devotees, regardless of their gender, possess equal potential for spiritual advancement and service to Krishna.[314] She further commends Prabhupada for opening up the Hare Krishna movement to women, despite cultural norms and traditional prescriptions.[315] In this way, she writes, Prabhupada took time, place, and circumstance into account and acted in the spirit of Krishna consciousness, “in the manner of Chaitanya”.[316]

Commenting on the role and degree of responsibility that Prabhupada's statements about women played in their abuse in ISKCON, E. Burke Rochford notes that Prabhupada’s personal example in dealings with his earliest women disciples was "far more important".[317] Their collective personal experiences, Rochford observes, portray Prabhupada’s "respectful attitude and behavior toward his women disciples"[317] and his empowerment for the same rights and duties as his male disciples.[318] Prabhupada encouraged and engaged women in conducting public scriptural discourses, kirtans and temple worship, writing for ISKCON magazines and publications, personally accompanying and assisting him, and assuming "significant institutional positions in ISKCON".[319][320]

Similarly, scholar of religion Akshay Gupta observes that Prabhupada did not regard his black disciples as lower or "untouchables",[321] displaying to some of them the same or even greater degree of affection than to his followers of other ethnicities.[321][p] Another scholar of religion Mans Broo adds that when Prabhupada speaks about castes, he referred to an envisioned “ideal society” in which people would be divided into different occupational groups “based not on hereditary but on individual qualifications”.[324]

Broo also notes that scholarly analyses[325] attribute some of such statements to Prabhupada's "flair for drama and overstatement"[326] — particularly noting his penchant for making politically incorrect remarks to reporters[324] and adding, “It is difficult to decide how seriously any single remark is meant to be taken from a transcript”. However, Broo concludes that this behavior does not clear Prabhupada from responsibility for his more radical of his politically incorrect statements.[327] [324] Another scholar of religion, Fred Smith, suggests that some of Prabhupada's statements (such as those concerning Hitler) “must be understood in the context of the intellectual and political culture in which he matured”[328] — specifically that of mid-twentieth-century Bengal,[305] brewing with anti-colonialist nationalism championed by such figures as Subhash Chandra Bose, and therefore more favorably disposed to Nazi Germany than to Great Britain.[328][q]

Broo notes that Prabhupada's followers continue to grapple with his controversial statements[325] — which paint "a picture of a not very pleasant man, one far removed from the Gaudiya Vaishnava ideals described in the classical texts of the tradition"[329] — and respond to them in different ways: Some remain silent, while others invoke context or argue that Prabhupada is being unfairly quoted due to negative biases. Still, others are willing to differentiate between his statements they deem "absolute" and those they consider "relative", acknowledging that some teachings may be contingent on the circumstances of Prabhupada's life before coming to the US.[330] However, some followers view this approach as "exceedingly risky", questioning who has the authority to determine which teachings are relative and which are not.[325] Therefore, Broo concludes, this issue is "not likely to be resolved soon".[325]

Commenting on the underlying causes for such controversies, scholar of religion Larry Shinn attributes the conflict between Prabhupada's teachings and western cultural values to "[Prabhupada]'s insistence on the infallibility of the Krishna scriptures and (...) the authenticity of Prabhupada’s Krishna faith and practice".[331][r]

By explaining the teachings of bhakti yoga and Gaudiya Vaishnavism and arousing interest in them worldwide, Prabhupada made a lasting contribution.[7][9][8] Through his writings and his movement, many Westerners have become aware of bhakti for the first time.[332] He translated and commented on important spiritual texts, particularly the Bhagavad-gita, the Srimad-Bhagavatam, and the Caitanya-caritamrta, making these texts accessible to a global audience.[220] His commentaries brought the traditional wisdom of these writings into a contemporary context, making possible a deeper comprehension of their spiritual meaning and its practical application in one’s life.[9] Within Gaudiya Vaishnavism, Prabhupada's preaching achievements are viewed as the fulfillment of a mission to introduce Caitanya Mahaprabhu's teachings to the world.[333]

Although the “steady procession of Hindu swamis” who had come to America before Prabhupada had generally aligned their views with the monistic Advaita Vedanta of Shankara (AD 788‒820) and the idea of “the ultimate absorption of the self into an impersonal Reality or Brahman”,[180] Prabhupada rejected Advaita Vedanta[334] and coherently argued that the Absolute is ultimately the Personality of Godhead.[335]

Sardella has written that in the twelve years between Prabhupada’s arrival in America and his demise, Prabhupada “managed to build ISKCON into an institution comprising thousands of dedicated members, establish Caitanya Vaishnava temples in most of the world’s major cities, and publish numerous volumes of Caitanya Vaishnava texts (in twenty-eight languages), tens of millions of which were distributed throughout the world”.[7][336] Prabhupada also spread the chanting of the Hare Krishna mantra worldwide.[336]

In 2013 Rochford wrote, “[T]he fact that ISKCON has survived for nearly 50 years, despite significant change, is a testament to the devotees’ resilience and to the power of Prabhupada’s teachings and vision for ISKCON”.[337]

In India Prabhupada’s movement has become a well-respected institution, with recognition at all levels of Hindu society.[338][339] ISKCON has large temple complexes active in cities like Mumbai, New Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai, and Kolkata.[340][341] ISKCON’s center in Mayapur has become an Eastern Indian place of pilgrimage for millions every year. Thousands of middle-class Hindus, both in India and elsewhere, have joined ISKCON.[340] And Hindus both in India and in the Hindu diaspora have provided ISKCON vast support.[339][342]

But Prabhupada's legacy also faces scrutiny on various fronts. Criticisms have emerged regarding the movement's organizational structure, controversies have arisen surrounding continuity of leadership after his passing,[343][344] and misdeeds and even criminal acts have been committed by some ISKCON members, including once-respected former leaders.[345][s] Concerns have been expressed about the movement's adaptability to modern values, especially concerning gender roles and societal norms.[346] And although ISKCON has benefited from the support and participation of a large and growing number of Indian families in its congregations outside India,[338][347] the “Hinduization” of ISKCON has in many places tended to diminish the involvement of other audiences.[348]

Nonetheless, Prabhupada's influence endures through his writings and ISKCON's ongoing activities.[7] Despite significant setbacks, the movement he started continues to grow.[349]

Kim Knott writes that scholars describe Prabhupada as a charismatic spiritual leader and emphasize his “humanity” and “uniqueness”.[350] Prabhupada’s missionary successes in such a short period, and at such an advanced age, she writes, are extolled by scholars using terms such as “stunning”, “remarkable”, and “extraordinary”.[350] In the same vein, Klaus Klostermaier, scholar of Hinduism and Indian history, refers to Prabhupada as "probably, the most successful propagator of Hinduism abroad".[8]

Representing such thoughts, Harvey Cox, American theologian and Professor of Divinity Emeritus at Harvard University, said:

There aren't many people you can think of who successfully implant a whole religious tradition in a completely alien culture. That's a rare achievement in the history of religion. In his case it's even all the more remarkable for his having done this at such an advanced age. When most people would have already retired, he began a whole new phase of his life by coming to the United States and initiating this movement. He began simply, with only a handful of disciples. Eventually he planted this movement deeply in the North American soil, throughout other parts of the European-dominated world, and beyond. Although I didn't know him personally, the fact that we now have in the West a vigorous, disciplined, and seemingly well-organized movement–not merely a philosophical movement or a yoga or meditation movement, but a genuinely religious movement--introducing the form of devotion to God that he taught, is a stunning accomplishment. So when I say [he’s] “one in a million,” I think that's in some ways an underestimate. Perhaps he was one in a hundred million.[10]

Prabhupada's success in spreading Indian spirituality among non-Indians across the world brought him acclaim from Indian political leaders.[11]

Indian Prime Ministers Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Deve Gowda,[351] Narendra Modi, and Indian Presidents Shankar Dayal Sharma, Pranab Mukherjee, and Pratibha Patil have praised Prabhupada, his work and mission.[11][352]

In 1998, speaking at the opening ceremony of an ISKCON temple in New Delhi, Prime Minister Vajpayee credited Prabhupada's movement with publishing the Bhagavad Gita "in millions of copies in scores of Indian languages" and distributing it "in all nooks and corners of the world",[340] calling Prabhupada's journey to the West and the rapid global propagation of his movement "one of the greatest spiritual events of the century".[340][t]

Releasing a 125-rupee commemorative coin on the occasion of Prabhupada's 125th birth anniversary,[354] Prime Minister Modi also praised Prabhupada for his efforts “to give India’s most priceless treasure to the world”, describing Prabhupada's accomplishments in spreading the thought and philosophy of India to the world as “nothing less than a miracle.”[353]

On the fiftieth anniversary of Prabhupada’s voyage to the West, US Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard praised the "compassion that drove Srila Prabhupada to attempt something so brave and so daring to deliver the message of Lord Chaitanya and the Holy Name to all of mankind".[355]

In keeping with Gaudiya-Vaisnava rites, after Prabhupada's death at the Krishna-Balarama temple in Vrindavan (Uttar Pradesh, India), his disciples interred his body on the temple premises and erected a marble samadhi, or shrine, over his burial site.[356][357] In Mayapur (West Bengal), they built a much larger pushpa-samadhi — a shrine sanctified with flowers from Prabhupada's burial ceremony.[358] Daily puja (traditional worship) is offered to larger-than-life statues of Prabhupada at both sites.[358]