Robert Byrd | |

|---|---|

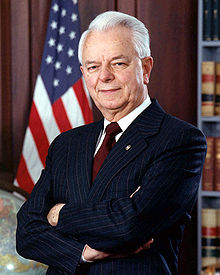

Official portrait, 2003 | |

| United States Senator from West Virginia | |

| In office January 3, 1959 – June 28, 2010 | |

| Preceded by | Chapman Revercomb |

| Succeeded by | Carte Goodwin |

| President pro tempore of the United States Senate | |

| In office January 3, 2007 – June 28, 2010 | |

| Preceded by | Ted Stevens |

| Succeeded by | Daniel Inouye |

| In office June 6, 2001 – January 3, 2003 | |

| Preceded by | Strom Thurmond |

| Succeeded by | Ted Stevens |

| In office January 3, 2001 – January 20, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Strom Thurmond |

| Succeeded by | Strom Thurmond |

| In office January 3, 1989 – January 3, 1995 | |

| Preceded by | John C. Stennis |

| Succeeded by | Strom Thurmond |

| President pro tempore emeritus of the United States Senate | |

| In office January 3, 2003 – January 3, 2007 | |

| Preceded by | Strom Thurmond |

| Succeeded by | Ted Stevens |

| Senate Majority Leader | |

| In office January 3, 1987 – January 3, 1989 | |

| Whip | Alan Cranston |

| Preceded by | Bob Dole |

| Succeeded by | George Mitchell |

| In office January 3, 1977 – January 3, 1981 | |

| Whip | Alan Cranston |

| Preceded by | Mike Mansfield |

| Succeeded by | Howard Baker |

| Senate Minority Leader | |

| In office January 3, 1981 – January 3, 1987 | |

| Whip | Alan Cranston |

| Preceded by | Howard Baker |

| Succeeded by | Bob Dole |

| Chair of the Senate Democratic Caucus | |

| In office January 3, 1977 – January 3, 1989 | |

| Preceded by | Mike Mansfield |

| Succeeded by | George Mitchell |

| Senate Majority Whip | |

| In office January 3, 1971 – January 3, 1977 | |

| Leader | Mike Mansfield |

| Preceded by | Ted Kennedy |

| Succeeded by | Alan Cranston |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from West Virginia's 6th district | |

| In office January 3, 1953 – January 3, 1959 | |

| Preceded by | Erland Hedrick |

| Succeeded by | John Slack |

| Member of the West Virginia Senate from the 9th district | |

| In office December 1, 1950 – December 23, 1952 | |

| Preceded by | Eugene Scott |

| Succeeded by | Jack Nuckols |

| Member of the West Virginia House of Delegates from Raleigh County | |

| In office January 1947 – December 1950 | |

| Preceded by | Multi-member district |

| Succeeded by | Multi-member district |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Cornelius Calvin Sale Jr. November 20, 1917 North Wilkesboro, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | June 28, 2010 (aged 92) Falls Church, Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Columbia Gardens Cemetery Arlington County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Erma James

(m. 1936; died 2006) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | Marshall University (BA) American University (JD) |

| Signature | |

Robert Carlyle Byrd (born Cornelius Calvin Sale Jr.; November 20, 1917 – June 28, 2010) was an American politician and musician who served as a United States senator from West Virginia for over 51 years, from 1959 until his death in 2010. A Democrat, Byrd also served as a U.S. representative for six years, from 1953 until 1959. He remains the longest-serving U.S. Senator in history; he was the longest-serving member in the history of the United States Congress[1][2][3][4] until surpassed by Representative John Dingell of Michigan.[5] Byrd is the only West Virginian to have served in both chambers of the state legislature and in both chambers of Congress.[6]

Byrd's political career spanned more than sixty years. He first entered the political arena by organizing and leading a local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1940s, an action he later described as "the greatest mistake I ever made."[7] He then served in the West Virginia House of Delegates from 1947 to 1950, and the West Virginia State Senate from 1950 to 1952. Initially elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1952, Byrd served there for six years before being elected to the Senate in 1958. He rose to become one of the Senate's most powerful members, serving as secretary of the Senate Democratic Caucus from 1967 to 1971 and—after defeating his longtime colleague Ted Kennedy for the job—as Senate Majority Whip from 1971 to 1977. Over the next 12 years, Byrd led the Democratic caucus as Senate Majority Leader and Senate Minority Leader. In 1989 he stepped down, following the pressure to make way for new party leadership.[8] As the longest serving Democratic senator, Byrd held the position of President pro tempore four times when his party was in the majority. This placed him third in the line of presidential succession, after the vice president and the Speaker of the House of Representatives.

Serving three different tenures as chairman of the United States Senate Committee on Appropriations enabled Byrd to steer a great deal of federal money toward projects in West Virginia.[9] Critics derided his efforts as pork barrel spending,[10] while Byrd argued that the many federal projects he worked to bring to West Virginia represented progress for the people of his state. Notably, Byrd strongly opposed Clinton's 1993 efforts to allow homosexuals to serve in the military and supported efforts to limit same-sex marriage.[11] Although he filibustered against the 1964 Civil Rights Act and supported the Vietnam War earlier in his career, Byrd's views changed considerably over the course of his life; by the early 2000s, he had completely renounced racism and segregation. Byrd was outspoken in his opposition to the Iraq War. Renowned for his knowledge of Senate precedent and parliamentary procedure, Byrd wrote a four-volume history of the Senate in later life. Near the end of his life, Byrd was in declining health and was hospitalized several times. He died in office on June 28, 2010, at the age of 92, and was buried at Columbia Gardens Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia.

Robert Byrd was born on November 20, 1917, as Cornelius Calvin Sale Jr.[12] in North Wilkesboro, North Carolina, to Cornelius Calvin Sale and his wife Ada Mae (Kirby).[13] When he was ten months old, his mother died on Armistice Day[14] during the 1918 flu pandemic. Byrd was the youngest of four[14] and in accordance with his mother's wishes, his father[12] dispersed the children among relatives. Calvin Jr. was adopted by his biological father's sister and her husband,[14] Vlurma and Titus Byrd, who changed his name to Robert Carlyle Byrd and raised him in the coal mining region of southern West Virginia, primarily in the coal town of Stotesbury, West Virginia.[3][15][16][17] Robert Byrd's biological father Calvin Sale went on to have four more children with his second wife, Ola (Pruitt) Sale.[18][19]

Byrd was educated in the public schools of Stotesbury.[20][21] Byrd played the violin at the Mark Twain School orchestra and the bass drum in the Mark Twain High School marching band.[22] He was the valedictorian of his 1934 graduating class at Stotesbury's Mark Twain High School.[23]

On May 29, 1937, Byrd married Erma Ora James (June 12, 1917 – March 25, 2006)[24] who was born to a coal mining family in Floyd County, Virginia.[25] Her family moved to Raleigh County, West Virginia, where she met Byrd when they attended the same high school.[26]

Robert Byrd had two daughters (Mona Byrd Fatemi and Marjorie Byrd Moore), six grandchildren, and seven great-grandchildren.[13]

In the early 1940s, Byrd recruited 150 of his friends and associates to create a new chapter of the Ku Klux Klan in Sophia, West Virginia.[12][16]

As a young boy, Byrd had witnessed his adoptive father walk in a Klan parade in Matoaka, West Virginia.[27] While growing up, Byrd had heard that "the Klan defended the American way of life against racemixers and communists".[28] He then wrote to Joel L. Baskin, Grand Dragon of the Realm of Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware, who responded that he would come and organize a chapter when Byrd had recruited 150 people.[27]

It was Baskin who told Byrd, "You have a talent for leadership, Bob ... The country needs young men like you in the leadership of the nation." Byrd later recalled, "Suddenly lights flashed in my mind! Someone important had recognized my abilities! I was only 23 or 24 years old, and the thought of a political career had never really hit me. But strike me that night, it did."[29] Byrd became a recruiter and leader of his chapter.[16] When it came time to elect the top officer (Exalted Cyclops) in the local Klan unit, Byrd won unanimously.[16][30]

In December 1944, Byrd wrote to segregationist Mississippi Senator Theodore G. Bilbo:

I shall never fight in the armed forces with a negro by my side ... Rather I should die a thousand times, and see Old Glory trampled in the dirt never to rise again than to see this beloved land of ours become degraded by race mongrels, a throwback to the blackest specimen from the wilds.

In 1946, Byrd wrote a letter to Samuel Green, the Ku Klux Klan's Grand Wizard, stating, "The Klan is needed today as never before, and I am anxious to see its rebirth here in West Virginia and in every state in the nation."[32] The same year, he was encouraged to run for the West Virginia House of Delegates by the Klan's grand dragon; Byrd won, and took his seat in January 1947.[33][34] However, during his campaign for the United States House of Representatives in 1952, he announced that, "after about a year, I became disinterested, quit paying my dues, and dropped my membership in the organization", and that during the nine years that have followed, he had never been interested in the Klan.[35] He said he had joined the Klan because he felt it offered excitement and was anti-communist, but also suggested his participation there "reflected the fears and prejudices" of the time.[16][33]

Byrd later called joining the KKK "the greatest mistake I ever made."[7] In 1997, he told an interviewer he would encourage young people to become involved in politics but also warned, "Be sure you avoid the Ku Klux Klan. Don't get that albatross around your neck. Once you've made that mistake, you inhibit your operations in the political arena."[36] In his last autobiography, Byrd explained that he was a KKK member because he "was sorely afflicted with tunnel vision— a jejune and immature outlook—seeing only what I wanted to see because I thought the Klan could provide an outlet for my talents and ambitions."[37] Byrd also said in 2005, "I know now I was wrong. Intolerance had no place in America. I apologized a thousand times ... and I don't mind apologizing over and over again. I can't erase what happened."[16]

Byrd worked as a gas station attendant, a grocery store clerk, a shipyard welder during World War II, and a butcher before he won a seat in the West Virginia House of Delegates in 1946, representing Raleigh County from 1947 to 1950.[13] Byrd became a local celebrity after a radio station in Beckley began broadcasting his "fiery fundamentalist lessons."[38] In 1950, he was elected to the West Virginia Senate, where he served from December 1950 to December 1952.[13]

In 1951, Byrd was among the official witnesses of the execution of Harry Burdette and Fred Painter, which was the first use of the electric chair in West Virginia.[39] In 1965 the state abolished capital punishment, with the last execution having occurred in 1959.[40]

Early in his career Byrd attended Beckley College, Concord College, Morris Harvey College, Marshall College, and George Washington University Law School,[13] and joined the Tau Kappa Epsilon fraternity.[41]

Byrd began night classes at American University Washington College of Law in 1953, while a member of the United States House of Representatives. He earned his Juris Doctor degree cum laude a decade later,[13] by which time he was a U.S. Senator. President John F. Kennedy spoke at the commencement ceremony on June 10, 1963, and presented the graduates their diplomas, including Byrd. Byrd completed law school in an era when only three years of undergraduate education were required. He later decided to complete his Bachelor of Arts degree in political science, and in 1994 he graduated summa cum laude from Marshall University.[3]

In 1952, Byrd was elected to the United States House of Representatives for West Virginia's 6th congressional district,[13] succeeding E. H. Hedrick, who retired from the House to make an unsuccessful run for the Democratic nomination for governor. Byrd was re-elected twice from this district, anchored in Charleston and also including his home in Sophia, serving from January 3, 1953, to January 3, 1959.[13] Byrd defeated Republican incumbent W. Chapman Revercomb for the United States Senate in 1958. Revercomb's record supporting civil rights had become an issue, playing in Byrd's favor.[13] Byrd was re-elected to the Senate eight times. He was West Virginia's junior senator for his first four terms; his colleague from 1959 to 1985 was Jennings Randolph, who had been elected on the same day as Byrd's first election in a special election to fill the seat of the late Senator Matthew Neely.

Despite his tremendous popularity in the state, Byrd ran unopposed only once, in 1976. On three other occasions—in 1970, 1994 and 2000—he won all 55 of West Virginia's counties. In his re-election bid in 2000, he won all but seven precincts. Congresswoman Shelley Moore Capito, the daughter of one of Byrd's longtime foes, former governor Arch Moore Jr., briefly considered a challenge to Byrd in 2006 but decided against it. Capito's district covered much of the territory Byrd had represented in the U.S. House.

In the 1960 Democratic Party presidential primaries, Byrd—a close Senate ally of Lyndon B. Johnson—endorsed and campaigned for Hubert Humphrey over front-runner John F. Kennedy in the state's crucial primary.[42] However, Kennedy won the state's primary and eventually the general election.[43]

Byrd was elected to a record ninth consecutive full Senate term in the November 7, 2006, midterm elections. He became the longest-serving senator in American history on June 12, 2006, surpassing Strom Thurmond of South Carolina with 17,327 days of service.[1] On November 18, 2009, Byrd became the longest-serving member in congressional history, with 56 years, 320 days of combined service in the House and Senate, passing Carl Hayden of Arizona.[2][3] Previously, Byrd had held the record for the longest unbroken tenure in the Senate (Thurmond resigned during his first term and was re-elected seven months later). He is the only senator ever to serve more than 50 years. Including his tenure as a state legislator from 1947 to 1953, Byrd's service on the political front exceeded 60 continuous years. Byrd, who never lost an election, cast his 18,000th vote on June 21, 2007, the most of any senator in history.[3][44] John Dingell broke Byrd's record as longest-serving member of Congress on June 7, 2013.[45]

Upon the death of former Florida Senator George Smathers on January 20, 2007, Byrd became the last living United States senator from the 1950s.[46]

Having taken part in the admission of Alaska and Hawaii to the union, Byrd was the last surviving senator to have voted on a bill granting statehood to a U.S. territory. At the time of Byrd's death, 14 sitting or former members of the Senate had not been born when Byrd's tenure in the Senate began, as well as then-President Barack Obama.

These are the committee assignments for Sen. Byrd's 9th and final term.

Byrd was a member of the wing of the Democratic Party that opposed federally-mandated desegregation and civil rights. However, despite his early career in the KKK, Byrd was linked to such senators as John C. Stennis, J. William Fulbright and George Smathers, who based their segregationist positions on their view of states' rights in contrast to senators like James Eastland, who held a reputation as a committed racist.[47]

Byrd joined with Southern Democratic senators to filibuster the Civil Rights Act of 1964,[48] personally filibustering the bill for 14 hours, a move he later said he regretted.[49] Despite an 83-day filibuster in the Senate, both parties in Congress voted overwhelmingly in favor of the Act (Democrats 47–16, Republicans 30–2) with Byrd voting against,[50] and President Johnson would later sign the bill into law.[51] He did not sign the 1956 Southern Manifesto,[52] and voted in favor of the Civil Rights Acts of 1960 and the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.[53][54] Byrd voted in favor of the initial House resolution for the Civil Rights Act of 1957 on June 18, 1957,[55] but voted against the Senate amendment to the bill on August 27, 1957.[56] Byrd voted against the Voting Rights Act of 1965,[57][58][59] as well as the confirmation of Thurgood Marshall to the U.S. Supreme Court.[60] However, he voted for the Civil Rights Act of 1968. In 2005, Byrd told The Washington Post that his membership in the Baptist church led to a change in his views. In the opinion of one reviewer, Byrd, like other Southern and border-state Democrats, came to realize that he would have to temper "his blatantly segregationist views" and move to the Democratic Party mainstream if he wanted to play a role nationally.[16]

In February 1968, Byrd questioned Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Earle Wheeler during the latter's testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee. During a White House meeting between President Johnson and congressional Democratic leaders on February 6, Byrd stated his concern for the ongoing Vietnam War, citing the U.S.'s lack of intelligence, preparation, underestimating of the morale and vitality of the Viet Cong, and overestimated how backed Americans would be by South Vietnam.[61]

President Johnson rejected Byrd's observations. "Anyone can kick a barn down. It takes a good carpenter to build one."[62]

During the 1968 Democratic Party presidential primaries, Byrd supported the incumbent president Johnson. Of the challenging Robert F. Kennedy, Byrd said, "Bobby-come-lately has made a mistake. I won't even listen to him. There are many who liked his brother—as Bobby will find out—but who don't like him."[63] Byrd praised Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley's police response to protest activity at that year's Democratic National Convention, stating that the violence that resulted was the fault of the protesters, while the police only tried to restore order.[64] Vice President Hubert Humphrey won the presidential nomination, and Byrd campaigned for him that fall.[65]

Byrd served in the Senate Democratic leadership. He succeeded George Smathers as secretary of the Senate Democratic Conference from 1967 to 1971.[13] He unseated Ted Kennedy in 1971 to become Majority Whip, the second highest-ranking Democrat, until 1977.[13] Smathers recalled that, "Ted was off playing. While Ted was away at Christmas, down in the islands, floating around having a good time with some of his friends, male and female, here was Bob up here calling on the phone. 'I want to do this, and would you help me?' He had it all committed so that when Teddy got back to town, Teddy didn't know what hit him, but it was already all over. That was Lyndon Johnson's style. Bob Byrd learned that from watching Lyndon Johnson." Byrd himself had told Smathers that "I have never in my life played a game of cards. I have never in my life had a golf club in my hand. I have never in life hit a tennis ball. I have—believe it or not—never thrown a line over to catch a fish. I don't do any of those things. I have only had to work all my life. And every time you told me about swimming, I don't know how to swim."[66]

In the 1976 Democratic Party presidential primaries, Byrd was the "favorite son" presidential candidate in West Virginia's primary. His easy victory gave him control of the delegation to the Democratic National Convention. Byrd had the inside track as Majority Whip but focused most of his time running for Majority Leader, more so than for re-election to the Senate, as he was virtually unopposed for his fourth term. By the time the vote for Majority Leader came, his lead was so secure that his lone rival, Minnesota's Hubert Humphrey, withdrew before the balloting took place. From 1977 to 1989 Byrd was the leader of the Senate Democrats, serving as Majority Leader from 1977 to 1981 and 1987 to 1989, and as Minority Leader from 1981 to 1987.[13]

Byrd was known for steering federal dollars to West Virginia, one of the country's poorest states. He was called the "King of Pork" by Citizens Against Government Waste.[67] After becoming chair of the Appropriations Committee in 1989, Byrd set a goal securing a total of $1 billion for public works in the state. He passed that mark in 1991, and funds for highways, dams, educational institutions, and federal agency offices flowed unabated over the course of his membership. More than 30 existing or pending federal projects bear his name. He commented on his reputation for attaining funds for projects in West Virginia in August 2006, when he called himself "Big Daddy" at the dedication for the Robert C. Byrd Biotechnology Science Center.[68][69] Examples of this ability to claim funds and projects for his state include the Federal Bureau of Investigation's repository for computerized fingerprint records as well as several United States Coast Guard computing and office facilities.[70]

Byrd was also known for using his knowledge of parliamentary procedure. Byrd frustrated Republicans with his encyclopedic knowledge of the inner workings of the Senate, particularly prior to the Reagan Era. From 1977 to 1979 he was described as "performing a procedural tap dance around the minority, outmaneuvering Republicans with his mastery of the Senate's arcane rules."[71] In 1988, majority leader Byrd moved a call of the Senate, which was adopted by the majority present, in order to have the Sergeant-at-Arms arrest members not in attendance. One member (Robert Packwood, R-Oregon) was carried feet-first back to the chamber by the Sergeant-at-Arms in order to obtain a quorum.[72][73]

As the longest-serving Democratic senator, Byrd served as President pro tempore four times when his party was in the majority:[13] from 1989 until the Republicans won control of the Senate in 1995; for 17 days in early 2001, when the Senate was evenly split between parties and outgoing Vice President Al Gore broke the tie in favor of the Democrats; when the Democrats regained the majority in June 2001 after Senator Jim Jeffords of Vermont left the Republican Party to become an independent; and again from 2007 to his death in 2010, as a result of the 2006 Senate elections. In this capacity, Byrd was third in the line of presidential succession at the time of his death, behind Vice President Joe Biden and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

|

Main article: Teachinghistory.org |

In 1969, Byrd launched a Scholastic Recognition Award; he also began to present a savings bond to valedictorians from high schools—public and private—in West Virginia. In 1985 Congress approved the nation's only merit-based scholarship program funded through the U.S. Department of Education, a program which Congress later named in Byrd's honor. The Robert C. Byrd Honors Scholarship Program initially comprised a one-year, $1,500 award to students with "outstanding academic achievement" who had been accepted at a college or university. In 1993, the program began providing four-year scholarships.[23]

In 2002 Byrd secured unanimous approval for a major national initiative to strengthen the teaching of "traditional American history" in K-12 public schools.[74] The Department of Education competitively awards $50 to $120 million a year to school districts (in amounts of about $500,000 to $1 million). The money goes to teacher training programs that are geared to improving the knowledge of history teachers.[75] The Continuing Appropriations Act, 2011 eliminated funding for the Robert C. Byrd Honors Scholarship Program.[76][77]

Television cameras were first introduced to the House of Representatives on March 19, 1979, by C-SPAN. Unsatisfied that Americans only saw Congress as the House of Representatives, Byrd and others pushed to televise Senate proceedings to prevent the Senate from becoming the "invisible branch" of government, succeeding in June 1986.

| External videos | |

|---|---|

To help introduce the public to the inner workings of the legislative process, Byrd launched a series of one hundred speeches based on his examination of the Roman Republic and the intent of the Framers. Byrd published a four-volume series on Senate history: The Senate: 1789–1989: Addresses on the History of the Senate.[78] The first volume won the Henry Adams Prize of the Society for History in the Federal Government as "an outstanding contribution to research in the history of the Federal Government." He also published The Senate of the Roman Republic: Addresses on the History of Roman Constitutionalism.[79]

In 2004, Byrd received the American Historical Association's first Theodore Roosevelt-Woodrow Wilson Award for Civil Service; in 2007, Byrd received the Friend of History Award from the Organization of American Historians. Both awards honor individuals outside the academy who have made a significant contribution to the writing and/or presentation of history. In 2014, The Byrd Center for Legislative Studies began assessing the archiving of Senator Byrd's electronic correspondence and floor speeches in order to preserve these documents and make them available to the wider community.[80]

On July 19, 2007, Byrd gave a 25-minute speech in the Senate against dog fighting in response to the indictment of football player Michael Vick.[81]

For 2007, Byrd was deemed the 14th-most powerful senator, as well as the 12th-most powerful Democratic senator.[82]

On May 19, 2008, Byrd endorsed then-Senator Barack Obama for president. One week after the 2008 West Virginia Democratic presidential primary, in which Hillary Clinton defeated Obama by 67 to 25 percent,[83] Byrd said, "Barack Obama is a noble-hearted patriot and humble Christian, and he has my full faith and support."[84] When asked in October 2008 about the possibility that the issue of race would influence West Virginia voters, as Obama is African American, Byrd replied, "Those days are gone. Gone!"[85] Obama lost West Virginia (by 13%) but won the election.

On January 26, 2009, Byrd was one of three Democrats to vote against the confirmation of Timothy Geithner as United States Secretary of the Treasury (along with Russ Feingold of Wisconsin and Tom Harkin of Iowa).[86]

On February 26, 2009, Byrd was one of two Democrats to vote against the District of Columbia House Voting Rights Act of 2009, which if it had become law would have added a voting seat in the United States House of Representatives for the District of Columbia and add a seat for Utah, explaining that he supported the intent of the legislation, but regarded it as an attempt to solve with legislation an issue which required resolution with a Constitutional amendment. (Democrat Max Baucus of Montana also cast a "nay" vote.)[87]

Although his health was poor, Byrd was present for every crucial vote during the December 2009 healthcare debate in the United States Senate; his vote was deemed essential so Democrats could obtain cloture to break a Republican filibuster. At the final vote on December 24, 2009, Byrd referenced recently deceased Senator Ted Kennedy, a devoted proponent, when casting his vote: "Mr. President, this is for my friend Ted Kennedy! Aye!"[88]

Byrd initially compiled a mixed record on the subjects of race relations and desegregation.[89] While he initially voted against civil rights legislation, in 1959 he hired one of the Capitol's first Black congressional aides, and he also took steps to integrate the United States Capitol Police for the first time since Reconstruction.[90] Beginning in the 1970s, Byrd explicitly renounced his earlier views in favor of racial segregation.[7][91] Byrd said that he regretted filibustering and voting against the Civil Rights Act of 1964[92] and would change it if he had the opportunity. Byrd also said that his views changed dramatically after his teenage grandson was killed in a 1982 traffic accident, which put him in a deep emotional valley. "The death of my grandson caused me to stop and think," said Byrd, adding he came to realize that African Americans love their children and grandchildren as much as he loved his.[93] During debate in 1983 over the passage of the law creating the Martin Luther King Jr. Day holiday, Byrd grasped the symbolism of the day and its significance to his legacy, telling members of his staff "I'm the only one in the Senate who must vote for this bill".[90]

Of the seven U.S. senators to vote on the confirmations of both Thurgood Marshall and Clarence Thomas to the United States Supreme Court (the others being Daniel Inouye of Hawaii, Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts, Quentin Burdick of North Dakota, Mark Hatfield of Oregon, and Fritz Hollings and Strom Thurmond of South Carolina), Byrd was the only senator to vote against confirming both of the first two African-American nominees to the Court in its history.[60][94] In Marshall's case, Byrd asked FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to look into the possibility that Marshall had either connections to communists or a communist past.[95] With respect to Thomas, Byrd stated that he was offended by Thomas's use of the phrase "high-tech lynching of uppity blacks" in his defense and that he was "offended by the injection of racism" into the hearing. He called Thomas's comments a "diversionary tactic" and said, "I thought we were past that stage". Regarding Anita Hill's sexual harassment charges against Thomas, Byrd supported Hill.[96] Byrd joined 45 other Democrats in voting against confirming Thomas to the Supreme Court.[97]

On March 29, 1968, Byrd criticized a Memphis, Tennessee, protest: "It was a shameful and totally uncalled for outburst of lawlessness undoubtedly encouraged to some considerable degree, at least, by his [Dr. King's] words and actions, and his presence. There is no reason for us to believe that the same destructive rioting and violence cannot, or that it will not, happen here if King attempts his so-called Poor People's March, for what he plans in Washington appears to be something on a far greater scale than what he had indicated he planned to do in Memphis."[98]

In a March 2, 2001, interview with Tony Snow, Byrd said of race relations:

They're much, much better than they've ever been in my life-time ... I think we talk about race too much. I think those problems are largely behind us ... I just think we talk so much about it that we help to create somewhat of an illusion. I think we try to have good will. My old mom told me, 'Robert, you can't go to heaven if you hate anybody.' We practice that. There are white niggers. I've seen a lot of white niggers in my time, if you want to use that word. We just need to work together to make our country a better country, and I'd just as soon quit talking about it so much.[99][100]

Byrd's use of the term "white nigger" created immediate controversy. When asked about it, Byrd's office provided this in a written response,

I apologize for the characterization I used on this program ... The phrase dates back to my boyhood and has no place in today's society ... In my attempt to articulate strongly held feelings, I have offended people that I never intended to offend.[101][100]

For the 2003–2004 session, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)[102] rated Byrd's voting record as being 100% in line with the NAACP's position on the thirty-three Senate bills they evaluated. Sixteen other senators received that rating. In June 2005, Byrd proposed an additional $10,000,000 in federal funding for the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C., remarking that, "With the passage of time, we have come to learn that his Dream was the American Dream, and few ever expressed it more eloquently."[103] Upon news of his death, the NAACP released a statement praising Byrd, saying that he "became a champion for civil rights and liberties" and "came to consistently support the NAACP civil rights agenda".[104]

Byrd initially said that the impeachment proceedings against Clinton should be taken seriously. Although he harshly criticized any attempt to make light of the allegations, he made the motion to dismiss the charges and effectively end the matter. Even though he voted against both articles of impeachment, he was the sole Democrat to vote to censure Clinton.[105]

Byrd strongly opposed Clinton's 1993 efforts to allow homosexuals to serve in the military and supported efforts to limit gay marriage. In 1996, before the passage of the Defense of Marriage Act, he said, "The drive for same-sex marriage is, in effect, an effort to make a sneak attack on society by encoding this aberrant behavior in legal form before society itself has decided it should be legal. [...] Let us defend the oldest institution, the institution of marriage between male and female as set forth in the Holy Bible."[11]

Despite his previous position, he later stated his opposition to the Federal Marriage Amendment and argued that it was unnecessary because the states already had the power to ban gay marriages.[106] However, when the amendment came to the Senate floor, he was one of the two Democratic senators who voted in favor of cloture.[107]

On March 11, 1982, Byrd voted against a measure sponsored by Senator Orrin Hatch that sought to reverse Roe v. Wade and allow Congress and individual states to adopt laws banning abortions. Its passing was the first time a congressional committee supported an anti-abortion amendment.[108][109]

In 1995, Byrd voted against a ban on intact dilation and extraction, a late-term abortion procedure typically referred to by its opponents as "partial-birth abortion".[110] In 2003, however, he voted for the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act, which prohibits intact dilation and extraction.[111] Byrd also voted against the 2004 Unborn Victims of Violence Act, which recognizes a "child in utero" as a legal victim if he or she is injured or killed during the commission of a crime of violence.[112]

In April 1970, the Senate Judiciary Committee approved a plan to replace the United States Electoral College with direct elections of presidents. Byrd initially opposed direct elections on the key vote and was one of two senators to switch votes in favor of the proposal during later votes.[113]

In April 1970, as the Senate Judiciary Committee delayed a vote on Supreme Court nominee Harry Blackmun, Byrd stated that "no nomination should be voted on within 24 hours after the hearing" after the previous two Supreme Court nominees had delays and was one of the 17 committee members who went on record of assuring Blackmun's nomination would be reported favorably to the full Senate.[114]

In October 1970, Byrd sponsored an amendment protecting members of Congress and those elected that have not yet assumed office. Byrd mentioned the 88 political assassinations in the United States and said state law was not adequate to handle the increase in political violence.[115]

In February 1971, after Fred R. Harris and Charles Mathias requested the Senate Rules Committee change the rules to permit selection of committee chairmen on a basis aside from seniority, Byrd indicated through his line of questioning that he saw considerable value in the seniority system.[116]

In April 1971, after Representative Hale Boggs stated that he had been tapped by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and called on FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to resign, Byrd opined that Boggs' imagination was involved and called on him to reveal any possible "good, substantial, bona fide evidence".[117]

In April 1971, Byrd met with President Nixon, Hugh Scott, and Robert P. Griffin for a briefing that after which Byrd, Scott, and Griffin asserted they had been told by Nixon of his intent to withdraw American forces from Indochina by a specific date. White House Press Secretary Ronald L. Ziegler disputed their claims by stating that the three had not been told anything by Nixon he had not mentioned in his speech the same day as the meeting.[118]

In April 1971, Jacob Javits, Fred R. Harris, and Charles H. Percy circulated letters to their fellow senators in an attempt to gain cosponsors for a resolution to appoint the Senate's first girl pages. Byrd maintained that the Senate was ill-equipped for girl pages and was among those that cited the long hours of work, the carrying of sometimes heavy documents and the high crime rate in the Capitol area as among the reasons against it.[119]

In September 1971, Representative Richard H. Poff was under consideration by President Nixon for a Supreme Court nomination, Byrd warning Poff that his nomination could be met with opposition by liberal senators and see a filibuster emerge. Within hours, Poff announced his declining of the nomination.[120]

In April 1972, Senate Majority Leader Mansfield announced that he had authorized Byrd to present an amendment to the Senate for a fixed deadline for total troop withdrawal that the Nixon administration would be obligated to meet and that the measure would serve as an amendment to the State Department‐United States Information Agency authorization bill.[121]

In April 1972, the Senate Judiciary Committee approved the nomination of Richard G. Kleindienst as United States Attorney General, Byrd being one of four Democrats to support the nomination.[122] On June 7, Byrd announced that he would vote against Kleindienst, saying in a news release that this was Nixon's first nomination that he had not voted to confirm and that testimony at hearings investigating Kleindienst's tenure at the International Telephone and Telegraph Corporation displayed "a show of arrogance and deception and insensitivity to the people's right to know."[123] During the confirmation hearings of Kleindienst's successor Elliot Richardson, Byrd insisted on the appointment of a special counsel to investigate the Watergate scandal as a condition for his appointment, eventually leading to the Archibald Cox investigation.[124]

In a May 1972 luncheon speech, Byrd criticized American newspapers for "an increasing tendency toward shoddy technical production" and observed that there was "a greater schism between the Nixon Administration and the media, at least publicly, than at any previous time in our history."[125]

In May 1972, Byrd introduced a proposal supported by the Nixon administration that would make cutting off all funding for American hostilities in Indochina conditional upon agreement on an internationally supervised cease‐fire. Byrd and Nixon supporters argued modification would bring the amendment more in line with President Nixon's proposal to withdraw all American forces from Vietnam the previous week and it was approved in the Senate by a vote of 47 to 43.[126]

In September 1972, Edward Brooke attempted to reintroduce his war ending amendment that had been defeated earlier in the week as an addendum to a clean drinking water bill when he discovered that Byrd had arranged a unanimous consent free agreement prohibiting amendments that were not relevant to the subject. Brooke charged the Byrd agreements with impairing his senatorial prerogatives to introduce amendments.[127]

During the 1972 general election campaign, Democratic nominee George McGovern advocated for partial amnesty for draft dodges. Byrd responded to the position in a November speech the day before the election without mentioning McGovern by name in saying, "How could we keep faith with the thousands of Americans we sent to Vietnam by giving a mere tap on the wrist to those who fled to Canada and Sweden?" Byrd said the welfare proposals were part of "pernicious doctrine that the Federal Government owes a living to people who don't want to work" and chastised individuals that had personal trips to Hanoi rather than official missions as "the Ramsey Clarks in our society who attempt to deal unilaterally with the enemy."[128]

In January 1973, the Senate passed legislation containing an amendment Byrd offered requiring President Nixon to give Congress an accounting of all funds that he had impounded and appropriated by February 5. Byrd stated that President Nixon had been required to submit reports to Congress and that he had not done so since June, leaving Congress in the dark on the matter.[129]

In February 1973, the Senate approved legislation requiring confirmation of the director and deputy director of the Office of Management and Budget in the White House in what was seen as "another battleground for the dispute between Congress and the White House over cuts in social spending programs in the current Federal budget and in the Nixon Administration's spending request for the fiscal year 1974, which begins next July 1". The legislation contained an amendment sponsored by Byrd limiting the budget officials to a maximum term of four years before having another confirmation proceeding. Byrd introduced another amendment that required all Cabinet officers be required to undergo reconfirmation by the Senate in the event that they are retained from one administration to another.[130]

In March 1973, Byrd led Senate efforts to reject a proposal that would have made most critical committee meetings open to the public, arguing that tampering with "the rides of the Senate is to tamper with the Senate itself" and argued against changing "procedures which, over the long past, have contributed to stability and efficiency in the operation of the Senate." The Senate voted down the proposal 47 to 38 on March 7.[131]

On May 2, 1973, the anniversary of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover's death, Byrd called on President Nixon to appoint a permanent successor for Hoover as FBI Director.[132]

In June 1973, Byrd sponsored a bill that would impose the first Tuesday in October as the date for all federal elections and mandate that states hold primary elections for federal elections between the first Tuesday in June and the first Tuesday in July. Senate Rules Committee approved the measure on June 13 and it was sent to the Senate floor for consideration.[133]

In June 1973, along with Lloyd Bentsen, Mike Mansfield, John Tower, and Jennings Randolph, Byrd was one of five senators to switch their vote on the foreign military aid authorization bill to assure its passage after previously voting against it.[134]

In October 1973, President Nixon vetoed the request of the United States Information Agency for $208 million for fiscal year 1974 on the grounds of a provision forcing the agency to provide any document or information demanded. Byrd introduced a bill identical to the one vetoed by Nixon the following month, differing in not containing the information provision as well as a ban on appropriating or spending more money than the annual budget called for, the Senate approving the legislation on November 13.[135]

In November 1973, after the Senate rejected an amendment to the National Energy Emergency Act intending to direct President Nixon to put gasoline rationing into effect on January 15, Byrd indicated the final vote not coming for multiple days.[136]

In June 1974, the Senate confirmed John C. Sawhill as Federal Energy Administrator only to rescind the confirmation hours later, the direct result of James Abourezk wanting to speak out and vote against the nomination due to the Nixon administration's refusal to roll back crude oil prices. Abourezk confirmed that he had asked Byrd for notice of when he could assume the Senate floor to deliver his remarks. Byrd was absent when present members passed the nomination as part of their efforts to clear the chamber's executive calendar and rescinded the confirmation.[137]

In May 1974, the House Judiciary Committee opened impeachment hearings against President Nixon after the release of 1,200 pages of transcripts of White House conversations between him and his aides and the administration became engulfed in the scandal that would come to be known as Watergate. That month, Byrd delivered a speech on the Senate floor opposing Nixon's potential resignation, saying it would serve only to convince the President's supporters that his enemies had driven him out of office: "The question of guilt or innocence would never be fully resolved. The country would remain polarized — more so than it is today. And confidence in government would remain unrestored." Most of the members of the Senate in attendance for the address were conservatives from both parties that shared opposition to Nixon being removed from office. Byrd was among multiple conservative senators who stated that they would not ask Nixon to resign.[138] Later that month, Republican attorney general Elliot L. Richardson termed Nixon "a law and order President who says subpoenas must be answered by everyone except himself," the comment being echoed by Byrd who additionally charged President Nixon with reneging on his public pledge that the independence of the special prosecutor to pursue the Watergate investigation would not be limited without the prior approval of a majority of congressional leaders.[139]

On July 29, Byrd met with Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, Minority Leader Hugh Scott, and Republican whip Robert P. Griffin in the first formality by Senate leaders on the matter of President Nixon's impeachment.[140] Byrd opposed Nixon being granted immunity. The New York Times noted that as Chairman of the Republican National Committee George H. W. Bush issued a formal statement indicating no chance for the Nixon administration to be salvaged, Byrd was advocating for President Nixon to face some punishment for the illegal activities of the administration and that former vice president Spiro Agnew should have been imprisoned.[141] The Senate leadership met throughout August 7 to discuss Nixon's fate, the topic of immunity being mentioned in the office of Hugh Scott.[142] Nixon announced his resignation the following day and resigned on August 9.[143] The resignation led to Congress rearranging their intent from an impeachment to the confirmation of a new vice presidential nominee and the Senate scheduled a recess between August 23 to September 14, Byrd opining, "What the country needs is for all of us to get out of Washington and let the country have a breath of fresh air."[144] By August 11, Hugh Scott announced he was finding fewer members of Congress from either party committed to criminally prosecuting former president Nixon over Watergate, Byrd and Majority Leader Mansfield both indicating their favoring for Nixon's culpability being left in the consideration of Special Prosecutor Leon Jaworski and the Watergate grand jury.[145]

On November 22, 1974, the Senate Rules Committee voted unanimously to recommend the nomination of Nelson Rockefeller as Vice President of the United States to the full Senate. Byrd admitted that he had preferred sending the nomination with no recommendation but was worried the act would apply prejudice to the nominee.[146]

In January 1975, after President Ford requested $300 million in additional military aid for South Vietnam and $222 million more for the Khmer Republic from Congress, Byrd said Ford and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had described the aid as "imperative" and that congressional leaders had been told North Vietnam would take over Saigon "little by little" if additional ammunition and other aid were not provided by the US to Saigon.[147] In February, along with Mike Mansfield, Hugh Scott, and Robert P. Griffin, Byrd was one of four senators to sponsor a compromise modification of the Senate's filibuster rule where three-fifths of the total Senate membership would be adequate in invoking closure on any measure except a change in the Senate's rules.[148] In March, while the Senate voted on reforming its filibuster rule, James B. Allen and other senators used their allotted time to speak at length and also force a series of votes. In response, Byrd said the group was engaging in an "exercise in futility" and that the chamber had already made up its mind.[149] In April, after President Ford and his administration's lawyers contended that Ford had authority as president to use troops under the War Powers Act, Byrd and Thomas F. Eagleton objected by charging that Ford was establishing a dangerous precedent.[150] Byrd issued a statement on the Senate floor admitting his "serious reservations" pertaining to the Ford administration's intent to bring roughly 130,000 South Vietnamese refugees to the United States, citing cultural differences and unemployment as raising "grave doubts about the wisdom of bringing any sizable number of evacuees here."[151] In May, after President Ford appealed for Americans to support the resettlement of 130,000 Vietnamese and Cambodians in the US, Byrd told reporters that he believed that President Ford's request for $507 million for refugee transport and resettlement would be reduced, citing its lack of political support in the United States.[152] In September, Byrd sponsored an amendment to the appropriations bill that if enacted would bar the education department from ordering busing to the school nearest to a pupil's home and sought to hold the Senate floor until there was an agreement among colleagues on his proposal. This failed, as the time limit for debating various proposals ran out.[153] On November 10, Byrd met with President Ford for a discussion on the New York loan guarantee bill.[154]

In April 1976, Byrd was one of five members of the Senate Select Committee to vote for a requirement that the proposed oversight committee would share Its jurisdiction with four committees that had authority over intelligence operations.[155] In June, after the Senate Judiciary Committee voted to send a bill breaking up 18 large oil companies into separate production, refining and refining‐marketing entities to the Senate floor, Byrd announced his opposition to divestiture and joined Republicans Hugh Scott and Charles Mathias in confirming their votes were to report the bill.[156] In September, Congress overrode President Ford's veto of a $56 billion appropriations bill for social services, Ford afterward telling Byrd and House Speaker Carl Albert that he would sign two bills supported by the Democrats.[157]

Byrd was elected majority leader on January 4, 1977.[158] On January 14, President Ford met with congressional leadership to announce his proposals for pay increases of high government officials, Byrd afterward telling reporters that the president had also stated his intent to recommend that the raises be linked to a code of conduct.[159] Days later, after the Senate established a special 15‐member committee to draw up a code of ethics for senators, Byrd told reporters that he was supportive of the measure and that it would be composed of eight Democrats and seven Republicans who would have until March 1 to issue a draft code that would then be subject to change by the full Senate.[160]

In January 1977, after President-elect Carter announced his nomination of Theodore C. Sorensen to be Director of Central Intelligence, Byrd admitted to reporters that there could be difficulty securing a Senate confirmation.[161] Conservative opposition to Sorenson's nomination led Carter to conclude that he could not be confirmed, and Carter withdrawing it without the Senate taking action.[162]

On January 18, 1977, after the Senate established a special 15‐member committee to draw up a code of ethics for senators, Byrd and Senate Minority Leader Howard Baker announced their support for the resolution, Byrd adding that knowledge of the code of ethics being enacted in the Senate would be privy to the public, press, and members of the Senate.[160] While eight of Carter's secretaries were confirmed within the first hours of his presidency, Byrd made an unsuccessful effort to secure a date and time limit for debate on the confirmation of F. Ray Marshall, Carter's nominee for United States Secretary of Labor.[163]

Between January and February 1979, Byrd proposed outlawing tactics frequently used to prevent him from bringing a bill to the floor for consideration. He stated the filibuster tactics gave the Senate a bad reputation and rendered it ineffective. His proposals initially earned the opposition of Republicans and conservative Democrats until there was a compromise for the reform package to be split and have the less objectionable part come up first for consideration. The Senate passed legislation curtailing tactics that had been used in the past to continue filibusters after cloture had been invoked on February 22.[164] In March, Byrd negotiated an agreement that a proposed amendment was referred to the Judiciary Committee and would be reported by April 10. The arrangement stated that Byrd could call up the proposed amendment any time following June 1 and his action would not be subject to a filibuster while the resolution embodying the amendment will.[165]

In October 1977, Byrd stated his refusal to authorize the Senate dropping consideration of the natural gas legislation under any circumstances, predicting the matter would be settled in the coming days as a result of conversations with colleagues he had the night before and a growing disillusion with filibusters in place of action on legislation. Byrd added that the deregulation bill would not become law due to it being identical to the Carter administration's proposal and President Carter's prior statement that he would veto deregulation bills.[166]

In May 1978, Byrd announced that he would not move to end a filibuster against the Carter administration's labor law revision bill until after the Memorial Day recess. The decision was seen as allowing wavering senators to not be cornered on their votes as lobbying efforts for both business and labor commenced and various opponents of the bill viewed Byrd's call as a sign of weakness toward the Carter administration. Byrd stated that his decision to wait was "to give ample time for debate on the measure" and that he was expecting the first petition to end the filibuster to come sometime following the Senate returning in June.[167]

In March 1979, after Attorney General Griffin Bell named a special counsel in the Carter warehouse investigation, Byrd stated his dissatisfaction with the move in a Senate floor speech, citing the existence of legislation approved by Congress the previous year that would allow the appointment of a special prosecutor.[168] In June, director of Public Citizen's Congress Watch Mark Green stated that President Carter had told him that Majority Leader Byrd had threatened that he would personally lead a filibuster against any attempt to extend controls on domestic oil prices. In response, Byrd's press secretary Mike Willard confirmed that Byrd told President Carter he would not vote for cloture in the event of a filibuster.[169] Days later, after the Senate voted to grant President Carter authority to set energy conservation targets for each of the 50 states and allow Carter to impose mandatory measures on any statfailed to implement a plan to meet the targets he set, Byrd reaffirmed his opposition to attempts aimed at President Carter's decision to remove price controls from crude oil produced within the United States.[170] In November, Byrd stated that the United States did not have an alternative to coal when attempting to meet its energy needs and that the technology needed to turn coal into liquid fuel at a lower cost than that of producing gasoline had already been made available, opining that doing this would solve most environmental problems.[171] Weeks later, Sergeant at Arms of the United States Senate F. Nordy Hoffman sent a letter to Byrd warning him to take precautions against possible attacks by religious fanatics and nationalist terrorists and advocating for senators to "vary their daily routines, take different routes to and from the Senate, exchange their personalized license plates for those that provide anonymity and be generally alert to the possibility of attack." Byrd distributed the letter to the other members of the chamber of Congress.[172] In December, the Senate voted on a Republican proposal to limit overall Government tax revenue that would also yield an annual tax cut of $39 to $55 billion over the course of the following four years. Republican William Roth sponsored an amendment that Byrd moved to table Senator Roth's request for a budget waiver and won by five votes. The Senate narrowly blocked the proposal.[173] By December, congressional leadership was aiming for President Carter to sign a new synthetic fuels bill before Christmas, with Byrd wanting the bill to contain a $185 billion revenue that was achieved in a minimum tax provision.[174] Later that month, after the Senate approved $1.5 billion in Federal loan guarantees for the Chrysler Corporation tonight after defeating a proposal to provide emergency, Byrd confirmed that he had spoken with United States Secretary of the Treasury G. William Miller about what Byrd called "excellent" chances that the Senate would complete work on a federal loans guarantees bill for Chrysler.[175]

In August 1980, Byrd stated that Congress was unlikely to pass a tax cut before the November elections despite the Senate being in the mood for passing one.[176]

In July 1978, Byrd introduced and endorsed a proposal by George McGovern for an amendment to repeal the 42‐month‐old embargo on American military assistance for Turkey that also linked any future aid for that country to progress on a negotiated settlement of the Cyprus problem. The Senate approved the amendment in a vote of 57 to 42 as part of a $2.9 billion international security assistance bill. Byrd stated that every government in the NATO alliance except Greece favored repeal of the embargo.[177]

In May 1979, Byrd stated that giving Turkey a grant should not be construed as retaliation against Greece and that aid for Turkey would improve Turkey's security in addition to that of Greece, NATO, and of American allies in the Middle East. Byrd mentioned his encouragement from the report on the Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities agreeing to resume negotiations on the island's future as well as reports that progress was also being made on the reintegration of Greece into NATO. Byrd furthered that American military installations in Turkey were "of major importance in the monitoring of Soviet strategic activities" and would have "obvious significance" in the goal of verifying compliance by the Soviet Union with the strategic arms treaty. The Senate approved the Turkey grant, to Byrd's wishes, but against that of both President Carter and the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.[178]

On February 2, 1978, Byrd and Minority Leader Baker invited all other senators to join them in sponsoring two amendments to the Torrijos–Carter Treaties, the two party leaders sending copies of amendments recommended by the Foreign Relations Committee the previous week.[179]

In January 1979, Byrd met with Deputy Prime Minister of China Deng Xiaoping for assurances by Deng that China hoped to unite Taiwan to the mainland by peaceful means and would fully respect "the present realities" on the island. Byrd afterward stated that his concern on the Taiwan question had been allayed.[180] In June, Byrd opined that a decision by President Carter to not proceed with the new missile system would kill the strategic arms limitation treaty in the Senate.[181] Byrd held meetings with Soviet leaders between July 3 to July 4. Following their conclusion, Byrd said he was still undecided on supporting the arms pact and that there had been talks on "the need on both sides for avoidance of inflammatory rhetoric which can only be counterproductive."[182] On September 23, Byrd stated that it was possible the Senate could complete the strategic arms limitation treaty that year but a delay until the following year could result in its defeat, adding that senators might have to remain in session during Christmas to ensure the treaty was voted on before 1979's end. Byrd noted that he was opposed to the treaty being "held hostage to the Cuban situation" as American interests could be harmed in the event the treaty was defeated solely due to Soviet Armed Forces troops being in Cuba.[183] In November, Byrd admitted to complaining to President Carter about Senate leadership receiving only occasional briefings about the Iranian hostage crisis and that Carter had agreed to daily consultations for Minority Leader Howard Baker, chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee Frank Church, and ranking Republican member of the Foreign Relations Committee Jacob Javits. Byrd added that he did not disagree with the move by the Carter administration to admit Mohammad Reza Pahlavi for hospitalization and that the same action would extend to "Ayatollah Khomeini himself if he were needing medical treatment and had a terminal illness."[184] On December 3, Byrd told reporters that the Iranian hostage crisis was making the Senate uninhabitable for a debate on the strategic arms treaty, noting that a discussion could still occur before the Senate adjourned on December 21 but that he did not believe he would call up the opportunity even if granted the chance.[185] Days later, Byrd announced there was no chance that the Senate would take up debate on the strategic arms treaty that year while speaking to reporters, adding that he would see no harm in having the discussion on the treaty begin in January of the following year.[186]

In July 1979, Senators Henry M. Jackson and George McGovern made comments expressing doubt on President Carter being assured as the Democratic nominee in the 1980 presidential election. When asked about their comments by a reporter, Byrd referred to Jackson and McGovern as "two very strong voices and not at all to be considered men who have little background in politics" but stated it was too early to participate in "writing the political obituary of the President at this point." Byrd added that the powers of the presidency made it possible that Carter could have a comeback and cited the events in November and December as being telling of his prospects of achieving higher popularity.[187]

On May 10, 1980, Byrd called for President Carter to debate Senator Ted Kennedy, who he complimented as having done a service for the US by raising key issues in his presidential campaign.[188] On August 2, Byrd advocated for an open Democratic National Convention where the delegates were not bound to a single candidate. The endorsement was seen as a break from President Carter.[189] In September, Byrd said that Republican presidential nominee Ronald Reagan had made comments on the Iran–Iraq War that were a disservice to the United States and that he was exercising "reckless political posturing" in foreign policy.[190]

In early 1990, Byrd proposed an amendment granting special aid to coal miners who would lose their jobs in the event that Congress passed clean air legislation. Byrd was initially confident in the number of votes he needed to secure its passage being made available but this was prevented by a vote from Democrat Joe Biden who said the measure's passage would mean an assured veto by President Bush. Speaking to reporters after its defeat, Byrd stated his content with the results: "I made the supreme effort. I did everything I could and, therefore, I don't feel badly about it."[191][192] The Senate passed clean air legislation within weeks of the vote on Byrd's amendment with the intent of reduction in acid rain, urban smog and toxic chemicals in the air and meeting the request by President Bush for a measure that was less costly than the initial plan while still performing the same tasks of combating clean air issues. Byrd was one of eleven senators to vote against the bill and said he "cannot vote for legislation that can bring economic ruin to communities throughout the Appalachian region and the Midwest."[193]

In August 1990, after the Senate passed its first major campaign finance reform bill since the Watergate era that would prevent political action committees from federal campaigns, lend public money into congressional campaigns and bestow candidates vouchers for television advertising, Byrd stated that he believed the bill would "end the money chase."[194]

Byrd authored an amendment to the National Endowment for the Arts that would bar the endowment from funding projects considered obscene such as depictions of sadomasochism, homo-eroticism, the sexual exploitation of children, or individuals engaged in sex acts while also requiring grant recipients to sign a pledge swearing their compliance with the restrictions. The October 1990 measure approved in the Senate was a bipartisan measure loosening government restrictions on art project funding and leaving courts to judge what art could be considered obscene.[195]

President Bush nominated Clarence Thomas for the Supreme Court. In October 1991, Byrd stated his support in the credibility of Anita Hill: "I believe what she said. I did not see on that face the knotted brow of satanic revenge. I did not see a face that was contorted with hate. I did not hear a voice that was tremulous with passion. I saw the face of a woman, one of 13 in a family of Southern blacks who grew up on the farm and who belonged to the church." Byrd questioned how members of the Senate could be convinced that Thomas would serve as an objective judge when he could refuse to watch Hill's testimony against him.[196]

In February 1992, the Senate turned down a Republican attempt sponsored by John McCain and Dan Coats to grant President Bush line-item veto authority and thereby be authorized to kill projects that he was opposed to, Byrd delivering an address defending congressional power over spending for eight hours afterward. The speech had been written by Byrd two years prior and he had at this point steered $1.5 billion to his state.[197]

In 1992, there was an effort made to pass a constitutional amendment to ensure a balanced federal budget. Byrd called the amendment "a smokescreen that will allow lawmakers to claim action against the deficit while still postponing hard budgetary decision" and spoke to reporters on his feelings against the amendment being passed: "Once members are really informed as to the mischief this amendment could do, and the damage it could do to the country and to the Constitution. I just have faith that enough members will take a courageous stand against the amendment." The sponsor of the amendment, Paul Simon, admitted that Byrd's prediction was not off and that other senators speak "when the chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee talks".[198]

In a June 1992 debate, Byrd argued in favor of the United States withdrawing accepting immigrants that did not speak English, the comment being a response to a plan from the Bush administration that would enable former Soviet states to receive American assistance and allow immigrants from a variety of countries to receive welfare benefits. Byrd soon afterward apologized for the comment and said they were due to his frustration over the federal government's inability to afford several essential services.[199]

In February 1994, the Senate passed a $10 billion spending bill that would mostly be allocated to Los Angeles, California earthquake victims and military operations abroad. Bob Dole, John Kerry, John McCain, and Russ Feingold partnered together to persuade the Senate in favor of cutting back the deficit expense. Byrd raised a procedural point to derail an attempt by Dole that would approve $50 billion in spending cuts over the following five years. McCain proposed killing highway demonstration projects with a $203 million price tag, leading Byrd to produce letters written by McCain that the latter had sent to the Appropriations Committee in 1991 in an attempt to gather highway grants for his home state of Arizona. Byrd said that McCain "is very considerate of the taxpayers when it comes to financing projects in other states, but he supports such projects in his own state."[200]

Along with Chuck Hagel, in July 1997 Byrd sponsored the Byrd–Hagel Resolution, which effectively prohibited the US from ratifying the Kyoto Protocol on limiting and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

In May 2000, Byrd and John Warner sponsored a provision threatening to withdraw American troops from Kosovo, the legislation if enacted cutting off funds for troops in Kosovo after July 1, 2001, without congressional consent. The language would have also withheld 25 percent of the money for Kosovo in the bill unless the assertion that European countries were living up to their promises to provide reconstruction money for the province was certified by President Clinton by July 15. Byrd argued that lawmakers had never approved nor debate whether American troops should be stationed in Kosovo. The Senate Appropriations Committee approved the legislation in a vote of 23-to-3 that was said to reflect "widespread concern among lawmakers about an open-ended deployment of American soldiers".[201]

In November 2000, Congress passed an amendment sponsored by Byrd diverting tariff revenues from the Treasury Department and instead allocating them to the industry complaining, the amount involved ranging from between $40 million and $200 million a year. The following month, Japan and the European Union led a group of countries in filing a joint complaint with the World Trade Organization to the law.[202]

Byrd praised the nomination of John G. Roberts to fill the vacancy on the Supreme Court created by the death of Chief Justice William Rehnquist. Likewise, Byrd was one of four Democrats who supported the confirmation of Samuel Alito to replace retiring Associate Justice Sandra Day O'Connor.[203][204]

Like most Democrats, Byrd opposed Bush's tax cuts and his proposals to change the Social Security program.

Byrd opposed the 2002 Homeland Security Act, which created the Department of Homeland Security, stating that the bill ceded too much authority to the executive branch.

On May 2, 2002, Byrd charged the White House with engaging in "sophomoric political antics", citing Homeland Security Advisor Tom Ridge's briefing of senators in another location instead of the Senate on how safe he felt the U.S. was.[205]

He also led the opposition to Bush's bid to win back the power to negotiate trade deals that Congress cannot amend, but lost overwhelmingly. In the 108th Congress, however, Byrd won his party's top seat on the new Homeland Security Appropriations Subcommittee.

In July 2004, Byrd released the New York Times best-selling book Losing America: Confronting a Reckless and Arrogant Presidency, which criticized the Bush presidency and the war in Iraq.

Byrd led a filibuster against the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002 granting President George W. Bush broad power to wage a "preemptive" war against Ba'athist Iraq, but he could not get even a majority of his own party to vote against cloture.[206]

Byrd was one of the Senate's most outspoken critics of the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Byrd anticipated the difficulty of fighting an insurgency in Iraq, stating on March 13, 2003,

If the United States leads the charge to war in the Persian Gulf, we may get lucky and achieve a rapid victory. But then we will face a second war: a war to win the peace in Iraq. This war will last many years and will surely cost hundreds of billions of dollars. In light of this enormous task, it would be a great mistake to expect that this will be a replay of the 1991 war. The stakes are much higher in this conflict.[207]

On March 19, 2003, when Bush ordered the invasion after receiving congressional approval, Byrd said,

Today I weep for my country. I have watched the events of recent months with a heavy, heavy heart. No more is the image of America one of strong, yet benevolent peacekeeper. The image of America has changed. Around the globe, our friends mistrust us, our word is disputed, our intentions are questioned. Instead of reasoning with those with whom we disagree, we demand obedience or threaten recrimination. Instead of isolating Saddam Hussein, we seem to have succeeded in isolating ourselves.[208]

Byrd also criticized Bush for his speech declaring the "end of major combat operations" in Iraq, which Bush made on the USS Abraham Lincoln. Byrd stated on the Senate floor,

I do not begrudge his salute to America's warriors aboard the carrier Lincoln, for they have performed bravely and skillfully, as have their countrymen still in Iraq. But I do question the motives of a deskbound president who assumes the garb of a warrior for the purposes of a speech.[209]

On October 17, 2003, Byrd delivered a speech expressing his concerns about the future of the nation and his unequivocal antipathy to Bush's policies. Referencing the Hans Christian Andersen children's tale The Emperor's New Clothes, Byrd said of the president: "the emperor has no clothes." Byrd further lamented the "sheep-like" behavior of the "cowed Members of this Senate" and called on them to oppose the continuation of a "war based on falsehoods."

In April 2004, Byrd mentioned the possibility of the Bush administration violating law by its failure to inform leadership in Congress midway through 2002 about its use of emergency anti-terror dollars to begin preparations for an invasion of Iraq. Byrd stated that he had never been told of a shift in money, a charge reported in the Bob Woodward book Plan of Attack, and its validation would mean "the administration failed to abide by the law to consult with and fully inform Congress."[210]

Byrd accused the Bush administration of stifling dissent:

The right to ask questions, debate, and dissent is under attack. The drums of war are beaten ever louder in an attempt to drown out those who speak of our predicament in stark terms. Even in the Senate, our history and tradition of being the world's greatest deliberative body is being snubbed. This huge spending bill—$87 billion—has been rushed through this chamber in just one month. There were just three open hearings by the Senate Appropriations Committee on $87 billion—$87 for every minute since Jesus Christ was born—$87 billion without a single outside witness called to challenge the administration's line.

Of the more than 18,000 votes he cast as a senator, Byrd said he was proudest of his vote against the Iraq war resolution.[211] Byrd also voted to tie a timetable for troop withdrawal to war funding.

On May 23, 2005, Byrd was one of 14 senators[212] (who became known as the "Gang of 14") to forge a compromise on the judicial filibuster, thus securing up and down votes for many judicial nominees and ending the threat of the so-called nuclear option that would have eliminated the filibuster entirely. Under the agreement, the senators retained the power to filibuster a judicial nominee in only an "extraordinary circumstance." It ensured that the appellate court nominees (Janice Rogers Brown, Priscilla Owen and William Pryor) would receive votes by the full Senate.

In 1977, Byrd was one of five Democrats to vote against the nomination of F. Ray Marshall as United States Secretary of Labor. Marshall was opposed by conservatives in both parties because of his pro-labor positions, including support for repealing right to work laws.[213] Marshall was confirmed and served until the end of Carter's term in 1981.

In February 1981, as the Senate voted on giving final approval to the $50 billion increase in the debt limit, Democrats initially opposed the measure as part of an effort to elicit the highest number of Republicans in support of the measure. Byrd proceeded to give a signal for Democrats that saw caucus members switch their votes in support of the increase.[214]

President Reagan was injured during an assassination attempt in March 1981. Following the shooting, Byrd opined that the aftermath of the attempt had proven there were "holes that need to be plugged" in the constitution's handling of the presidential line of succession after a president's disability and stated his intent to introduce legislation calling for a mandatory life sentence for anyone attempting to assassinate a president, vice president, or member of Congress.[215]

In March 1981, during a Capitol Hill interview, Byrd stated that the Reagan administration was promoting an economic package with assumptions for the national economy that might take a year for the public to see its difficulties and thereby lead to a political backlash. Byrd contented that President Reagan would win approval by Congress of $35 to $40 billion of the $48 billion in proposed budget cuts while having more difficulty in passing his tax-cut package, asserting Democratic opposition and some Republicans having misgivings about the approach as the reason Congress would block the plan and furthering that he would be surprised if a one-year cut in rates lasted more than year. Byrd opined that it was time for "some tax reform" that would see loopholes closed for the rich dropped to bring in revenues and expressed belief in the likelihood of the administration dismantling existing energy programs: "Energy programs are not as catchy now as budget cuts. But if the gas lines begin to form again, or the overseas oil gets cut off, we will have lost the time, the momentum, the money. Basically, they have a wholesale dismantlement of the energy programs we spent several years creating around here."[216]

In March 1981, during a news conference, Byrd stated that the Reagan administration had not established a coherent foreign policy. He credited conflicting statements from administration officials with having contributed to confusion in Western European capitals. Byrd also said, "We've seen these statements, and backing and filling, and the secretary of state has been kept pretty busy explaining and denying assertions and pronouncements by others, which indeed indicate that the administration has not yet got its foreign policy act together."[217]