| Part of a series on the |

| American Revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

The Lee Resolution, also known as "The Resolution for Independence", was the formal assertion passed by the Second Continental Congress on July 2, 1776, resolving that the Thirteen Colonies (then referred to as the United Colonies) were "free and independent States" and separate from the British Empire. This created what became the United States of America, and news of the act was published that evening in The Pennsylvania Evening Post and the following day in The Pennsylvania Gazette. The Declaration of Independence, which officially announced and explained the case for independence, was approved two days later, on July 4, 1776.

The resolution is named for Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, who proposed it to Congress after receiving instructions and wording from the Fifth Virginia Convention and its President Edmund Pendleton. Lee's full resolution had three parts which were considered by Congress on June 7, 1776. Along with the independence issue, it also proposed to establish a plan for ensuing American foreign relations, and to prepare a plan of a confederation for the states to consider. Congress decided to address each of these three parts separately.

Some sources indicate that Lee used the language from the Virginia Convention's instructions almost verbatim. Voting was delayed for several weeks on the first part of the resolution while state support and legislative instruction for independence were consolidated, but the press of events forced the other less-discussed parts to proceed immediately. On June 10, Congress decided to form a committee to draft a declaration of independence in case the resolution should pass; the following day, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston were appointed as the Committee of Five to accomplish this. That same day, Congress decided to establish two other committees to develop the resolution's last two parts. The following day, another committee of five (John Dickinson, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Benjamin Harrison V, and Robert Morris) was established to prepare a plan of treaties to be proposed to foreign powers; a third committee was created, consisting of one member from each colony, to prepare a draft of a constitution for confederation of the states.

The committee appointed to prepare a plan of treaties made its first report on July 18, largely in the writing of John Adams. A limited printing of the document was authorized, and it was reviewed and amended by Congress over the next five weeks. On August 27, the amended plan of treaties was referred back to the committee to develop instructions concerning the amendments, and Richard Henry Lee and James Wilson were added to the committee. Two days later, the committee was empowered to prepare further instructions and report back to Congress. The formal version of the plan of treaties was adopted on September 17. On September 24, Congress approved negotiating instructions for commissioners to obtain a treaty with France, based on the template provided in the plan of treaties; the next day, Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane, and Thomas Jefferson were elected commissioners to the court of France.[1] Alliance with France was considered vital if the war with Britain was to be won and the newly declared country was to survive.

The committee drafting a plan of confederation was chaired by John Dickinson; they presented their initial results to Congress on July 12, 1776. Long debates followed on such issues as sovereignty, the exact powers to be given the confederate government, whether to have a judiciary, and voting procedures.[2] The final draft of the Articles of Confederation was prepared during the summer of 1777 and approved by Congress for ratification by the individual states on November 15, 1777, after a year of debate.[3] It continued in use from that time onward, although it was not ratified by all states until almost four years later on March 1, 1781.

When the American Revolutionary War began in 1775, few colonists in British North America openly advocated independence from Great Britain. Support for independence grew steadily in 1776, especially after the publication of Thomas Paine's pamphlet Common Sense in January of that year. In the Second Continental Congress, the movement towards independence was guided principally by an informal alliance of delegates eventually known as the "Adams-Lee Junto", after Samuel Adams and John Adams of Massachusetts and Richard Henry Lee of Virginia.

On May 15, 1776, the revolutionary Virginia Convention, then meeting in Williamsburg, passed a resolution instructing Virginia's delegates in the Continental Congress "to propose to that respectable body to declare the United Colonies free and independent States, absolved from all allegiance to, or dependence upon, the Crown or Parliament of Great Britain".[4] In accordance with those instructions, on June 7, Richard Henry Lee proposed the resolution to Congress and it was seconded by John Adams.

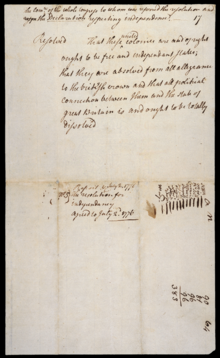

Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances.

That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation.

Congress as a whole was not yet ready to declare independence at that moment, because the delegates from some of the colonies, including Maryland, Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, and New York, had not yet been authorized to vote for independence.[5] Voting on the first clause of Lee's resolution was therefore postponed for three weeks while advocates of independence worked to build support in the colonial governments for the resolution.[6] Meanwhile, a Committee of Five was appointed to prepare a formal declaration so that it would be ready when independence, which almost everyone recognized was now inevitable, was approved. The committee prepared a declaration of independence, written primarily by Thomas Jefferson, and presented it to Congress on June 28, 1776.

The declaration was set aside while the resolution of independence was debated for several days. The vote on the independence section of the Lee resolution had been postponed until Monday, July 1, when it was taken up by the Committee of the Whole. At the request of South Carolina, the resolution was not acted upon until the following day in the hope of securing unanimity. A trial vote had been tested where it was found that South Carolina and Pennsylvania were in the negative, with Delaware split in a tie between its two delegates. The vote was held on July 2, with critical changes happening between Monday and Tuesday. Edward Rutledge was able to persuade South Carolina delegates to vote yes, two Pennsylvania delegates were persuaded to be absent, and Caesar Rodney had been sent for through the night to break Delaware's tie,[7] so Lee's resolution of independence was approved by 12 of the 13 colonies. Delegates from the Colony of New York still lacked instructions to vote for independence, so they abstained on this vote, although the New York Provincial Congress voted on July 9 to "join with the other colonies in supporting" independence.[8]

The Lee Resolution's passage was reported at the time as the colonies' definitive declaration of independence from Great Britain. The Pennsylvania Evening Post reported on July 2:

This day the CONTINENTAL CONGRESS declared the UNITED COLONIES FREE and INDEPENDENT STATES.[9]

The Pennsylvania Gazette followed suit the next day with its own brief report:

Yesterday, the CONTINENTAL CONGRESS declared the UNITED COLONIES FREE and INDEPENDENT STATES.[10]

After passing the resolution of independence on July 2, Congress turned its attention to the text of the declaration. Over several days of debate, Congress made a number of alterations to the text, including adding the wording of Lee's resolution of independence to the conclusion. The final text of the declaration was approved by Congress on July 4 and sent off to be printed.

John Adams wrote his wife Abigail on July 3 about the resolution of independence:

The second day of July, 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.[11]

Adams's prediction was off by two days. From the outset, Americans celebrated Independence Day on July 4, the date when the Declaration of Independence was approved, rather than on July 2, the date when the resolution of independence was adopted.

The two latter parts of the Lee Resolution were not passed until months later. The second part regarding the formation of foreign alliances was approved in September 1776, and the third part regarding a plan of confederation was approved in November 1777 and finally ratified in 1781.

The following are entries relating to the resolution of independence and the Declaration of Independence in the Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, from American Memory, published by the Library of Congress: