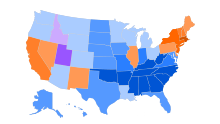

Religious affiliation in the United States, per Gallup, Inc. (2023)[1]

| Religion by country |

|---|

|

|

Religion in the United States is widespread and diverse, with the country being far more religious than other wealthy Western nations.[2] An overwhelming majority of Americans believe in a higher power,[3] engage in spiritual practices,[4] and consider themselves religious or spiritual.[5][6] Christianity is the most widely professed religion, with the majority of Americans being Evangelicals, Mainline Protestants, or Catholics.[7][8]

Freedom of religion is guaranteed in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. Many scholars of religion credit this and the country's separation of church and state for its high level of religiousness;[9] lacking a state church, it completely avoided the experiences of religious warfare and conflict that characterized European modernization.[10] Its history of religion has always been marked by religious pluralism and diversity.[11][12] In colonial times, Anglicans, Quakers, and other mainline Protestants, as well as Mennonites, arrived from Northwestern Europe. Various dissenting Protestants who had left the Church of England greatly diversified the religious landscape. The Episcopal Church, splitting from the Church of England, came into being in the American Revolution.

The religiosity of the country has changed over time.[13] Religious involvement among American citizens has gradually grown from 17% in 1776 to 62% in 2000.[14] The Thirteen Colonies were initially marked by low levels of religiosity.[13][15] The two Great Awakenings — the first in the 1730s and 1740s, the second between the 1790s and 1840s — led to an immense rise in observance and gave birth to many evangelical Protestant denominations. When they began, one in ten Americans were members of congregations; by the time they ended, eight in ten were.[13] The aftermath led to what historian Martin Marty calls the "Evangelical Empire", a period in which evangelicals dominated U.S. cultural institutions. They supported measures to abolish slavery, further women's rights, enact prohibition, and reform education and criminal justice.[16]

New Protestant branches like Adventism emerged; Restorationists like the Jehovah's Witnesses, the Latter Day Saint movement, Churches of Christ and Church of Christ, Scientist, as well as Unitarian and Universalist communities all spread in the 19th century. Deism also found support among American upper classes and intellectual thinkers. During the immigrant waves of the mid to late 19th and 20th century, an unprecedented number of Catholic and Jewish immigrants arrived in the United States. Pentecostalism emerged in the early 20th century as a result of the Azusa Street Revival. Unitarian Universalism resulted from the merge of Unitarian and Universalist churches in the 20th century.

The U.S. has the largest Christian and Protestant population in the world.[17] Judaism is the second-largest religion in the U.S., practiced by 2% of the population, followed by Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam, each with 1% of the population.[18] Mississippi is the most religious state in the country, with 63% of its adult population described as very religious, while New Hampshire, with only 20% of its adult population described as very religious, is the least religious state.[19] Congress overwhelmingly identifies as religious and Christian; both the Republican and Democratic parties generally nominate those who are.[20][21] The Christian left, as seen through figures such as Martin Luther King Jr., Jimmy Carter, and William Jennings Bryan; along with many figures within the Christian right have had a significant role in the country's politics.

Pew Research Center surveys conclude that "the religiously unaffiliated share of the population, consisting of people who describe their religious identity as atheist, agnostic or 'nothing in particular,' now stands at 26%, up from 17% in 2009" and that "both Protestantism and Catholicism are experiencing losses of population share."[22][23] Many of the unaffiliated retain religious beliefs or practices without affiliating.[24][25][26] There have been variant proposed explanations for secularization including lack of trust in the labor market, with government, in marriage and in other aspects of life[27], backlash against the religious right in the 1980s[28], sexual abuse scandals, particularly those within the Southern Baptist Convention[29] and Catholic Church.[30]

History

Ever since its early colonial days, when some Protestant dissenter English and German settlers moved in search of religious freedom, America has been profoundly influenced by religion.[31] Throughout its history, religious involvement among American citizens has grown since 1776 from 17% of the US population to 62% in 2000.[14] Approximately 35-40 percent of Americans regularly attended religious services from eighteenth-century colonial America up to 1940.[9] That influence continues in American culture, social life, and politics.[32] Several of the original Thirteen Colonies were established by settlers who wished to practice their own religion within a community of like-minded people: the Massachusetts Bay Colony was established by English Puritans (Congregationalists), Pennsylvania by British Quakers, Maryland by English Catholics, and Virginia by English Anglicans. Despite these, and as a result of intervening religious strife and preference in England[33] the Plantation Act 1740 would set official policy for new immigrants coming to British America until the American Revolution. While most settlers and colonists during this time were Protestant, a few early Catholic and Jewish settlers also arrived from Northwestern Europe into the colonies; however, their numbers were very slight compared to the Protestant majority. Even in the "Catholic Proprietary" or colony of Maryland, the vast majority of Maryland colonists were Protestant by 1670.[34]

The text of the First Amendment in the U.S. Constitution states that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."[35] It guarantees the free exercise of religion while also preventing the government from establishing a state religion. However, the states were not bound by the provision, and as late as the 1830s Massachusetts provided tax money to local Congregational churches.[36] Since the 1940s, the Supreme Court has interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment as applying the First Amendment to state and local governments.[citation needed]

President John Adams and a unanimous Senate endorsed the Treaty of Tripoli in 1797 that stated: "the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion."[37]

Expert researchers and authors have referred to the United States as a "Protestant nation" or "founded on Protestant principles",[38][39][40][41] specifically emphasizing its Calvinist heritage.[42][43]

The modern official motto of the United States of America, as established in a 1956 law signed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, is "In God We Trust".[44][45][46] The phrase first appeared on U.S. coins in 1864.[45]

According to a 2002 survey by the Pew Research Center, nearly 6 in 10 Americans said that religion plays an important role in their lives, compared to 33% in Great Britain, 27% in Italy, 21% in Germany, 12% in Japan, and 11% in France. The survey report stated that the results showed America having a greater similarity to developing nations (where higher percentages say that religion plays an important role) than to other wealthy nations, where religion plays a minor role.[2]

In 1963, 90% of U.S. adults claimed to be Christians while only 2% professed no religious identity.[citation needed] In 2016, 73.7% identified as Christians while 18.2% claimed no religious affiliation.[47]

Freedom of religion

According to Noah Feldman, the United States federal government was the first government to be designed with no established religion at all.[dubious – discuss][49] However, some states established religions until the 1830s.

Modeling the provisions concerning religion within the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, the framers of the Constitution rejected any religious test for office, and the First Amendment specifically denied the federal government any power to enact any law respecting either an establishment of religion or prohibiting its free exercise, thus protecting any religious organization, institution, or denomination from government interference. The decision was mainly influenced by European Rationalist and Protestant ideals, but was also a consequence of the pragmatic concerns of minority religious groups and small states that did not want to be under the power or influence of a national religion that did not represent them.[50]

Measuring religion

Census and independent polling

Since the first American census in 1790, census forms have never asked the religion of participants, with Vincent P. Barabba, former head of the United States Census Bureau, stating in April 1976 that "asking such a question in the decennial census, in which replies are mandatory, would appear to infringe upon the traditional separation of church and state" and "could affect public cooperation in the census". Data on religious affiliation comes from independent pollsters[51] by the Pew Research Center and other agencies or, on membership, from religious associations, such the Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches of the National Council of Churches.

Inaccuracies of independent polling

Independent polling results on religion are generally questionable due to numerous factors:[52]

- polls consistently fail to predict political election outcomes, signifying consistent failure to capture the actual views of the population

- very low response rates for all polls since the 1990s

- biases in wording or topic affect how people respond to polls

- polls categorize people based on limited choices

- polls often generalize broadly

- polls have shallow or superficial choices, which complicate capturing complexity of religious beliefs and practices

- poll interviewer and respondent fatigue is very common

Researchers note that an estimated 20-40% of the population changes their self-reported religious affiliation/identity over time due to numerous factors and that usually it is their answers on surveys that change, not necessarily their religious practices or beliefs.[53]

Researchers advise caution when looking at the "Nones" demographics on surveys because different surveys systematically have discrepancies that amount to 8% and growing of estimates, part of it being that the respondents on surveys are not consistent and also the questions asked are worded differently, generating consistent discrepancies in responses.[54]

According to Gallup there are variations on the responses based on how they ask questions. They routinely ask on complex things like belief in God since the early 2000s in 3 different wordings and they constantly receive 3 different percentages in responses.[55]

Christianity

The most popular religion in the U.S. is Christianity, comprising the majority of the population (73.7% of adults in 2016), with the majority of American Christians belonging to a Protestant denomination or a Protestant offshoot (such as Mormonism or the Jehovah's Witnesses).[56] According to the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies newsletter published March 2017, based on data from 2010, Christians were the largest religious population in all 3,143 counties in the country.[57] Roughly 48.9% of Americans are Protestants, 23.0% are Catholics, 1.8% are Mormons (members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints).[56] Christianity was introduced during the period of European colonization. The United States has the world's largest Christian population.[58][59]

According to membership statistics from current reports and official web sites, the five largest Christian denominations are:

- The Catholic Church in the United States, 71,000,000 members[60]

- The Southern Baptist Convention, 13,680,493 members[61]

- The National Baptist Convention, USA, Inc., 8,415,100 members[62]

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6,920,086 members[63]

- The United Methodist Church, 5,714,815 members[64]

The Southern Baptist Convention, with over 13 million adherents, is the largest of more than 200[65] distinctly named Protestant denominations.[66] In 2007, members of evangelical churches comprised 26% of the American population, while another 18% belonged to mainline Protestant churches, and 7% belonged to historically black churches.[67]

A 2015 study estimates some 450,000 Christian believers from a Muslim background in the country, most of them belonging to some form of Protestantism.[68] In 2010 there were approximately 180,000 Arab Americans and about 130,000 Iranian Americans who converted from Islam to Christianity. Dudley Woodbury, a Fulbright scholar of Islam, estimates that 20,000 Muslims convert to Christianity annually in the United States.[69]

Protestant denominations

Beginning around 1600, Northwestern European settlers introduced the Anglican and Puritan religion, as well as Baptist, Presbyterian, Lutheran, Quaker, and Moravian denominations.[70] Historians agree that members of mainline Protestant denominations have played leadership roles in many aspects of American life, including politics, business, science, the arts, and education. They founded most of the country's leading institutes of higher education.[71] According to Harriet Zuckerman, 72% of American Nobel Prize laureates between 1901 and 1972, have identified from Protestant background.[72]

Episcopalians[73] and Presbyterians[74] tend to be considerably wealthier and better educated than most other religious groups, and numbers of the most wealthy and affluent American families as the Vanderbilts[73] and Astors,[73] Rockefeller,[75][76] Du Pont,[76] Roosevelt, Forbes, Fords,[76] Whitneys,[73] Morgans[73] and Harrimans are Mainline Protestant families,[73] though those affiliated with Judaism are the wealthiest religious group in the United States[77][78] and those affiliated with Catholicism, owing to sheer size, have the largest number of adherents of all groups (14 million) in the top income bracket if each Protestant denomination is divided into separate groups (though the overall percentage of Catholics in high income brackets is far lower than the percentage of any Mainline Protestant group in high income brackets, and the percentage of Catholics in high income brackets is comparable to the percentage of Americans in general in high income brackets.)[79]

Some of the first colleges and universities in America, including Harvard,[80] Yale,[81] Princeton,[82] Columbia,[83] Dartmouth,[84] Pennsylvania,[85][86] Duke,[87] Boston,[88] Williams, Bowdoin, Middlebury,[89] and Amherst, all were founded by mainline Protestant denominations. By the 1920s most had weakened or dropped their formal connection with a denomination. James Hunter argues:

- The private schools and colleges established by the mainline Protestant denominations, as a rule, still want to be known as places that foster values, but few will go so far as to identify those values as Christian.... Overall, the distinctiveness of mainline Protestant identity has largely dissolved since the 1960s.[90]

Great Awakenings and other Protestant descendants

Several Christian groups were founded in America during the Great Awakenings. Interdenominational evangelicalism and Pentecostalism emerged; new Protestant denominations such as Adventism; non-denominational movements such as the Restoration Movement (which over time separated into the Churches of Christ, the Christian churches and churches of Christ, and the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)); Jehovah's Witnesses (called "Bible Students" in the latter part of the 19th century); and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormonism).

Catholicism

While the Puritans were securing their Commonwealth, members of the Catholic church in England were also planning a refuge, "for they too were being persecuted on account of their religion."[92] Among those interested in providing a refuge for Catholics was the second Lord of Baltimore, George Calvert, who established Maryland, a "Catholic Proprietary", in 1634,[92] more than sixty years after the founding of the Spanish Florida mission of St. Augustine.[93] The first US Catholic university, Georgetown University, was founded in 1789. Though small in number in the beginning, Catholicism grew over the centuries to become the largest single denomination in the US, primarily through immigration, but also through the acquisition of continental territories under the jurisdiction of French and Spanish Catholic powers.[94] Though the European Catholic and indigenous population of these former territories were small,[95] the material cultures there, the original mission foundations with their canonical Catholic names, are still recognized today (as they were formerly known) in any number of cities in California, New Mexico and Louisiana. (The most recognizable cities of California, for example, are named after Catholic saints.)

While Catholic Americans were present in small numbers early in United States history, both in Maryland and in the former French and Spanish colonies that were eventually absorbed into the United States, the vast majority of Catholics in the United States today derive from unprecedented waves of immigration from primarily Catholic countries and regions (Ireland was still part of the United Kingdom until 1921 and German unification didn't officially occur until 1871)[96] during the mid-to-late 19th and 20th century. Irish, Hispanic, Italian, Portuguese, French Canadian, Polish, German,[97] and Lebanese (Maronite) immigrants largely contributed to the growth in the number of Catholics in the United States. Irish and German Catholics, by far, provided the greatest number of Catholic immigrants before 1900. From 1815 until the close of the Civil War in 1865, 1,683,791 Irish Catholics immigrated to the US. The German states followed, providing "the second largest immigration of Catholics, clergy and lay, some 606,791 in the period 1815-1865, and another 680,000 between 1865 and 1900, while the Irish immigration in the latter period amounted to only 520,000."[98] Of the four major national groups of clergy (early and mid-19th century)—Irish, German, Anglo-American, and French—"the French emigre priests may be said to have been the outstanding men, intellectually."[99] As the number of Catholics increased in the late 19th and 20th century, they built up a vast system of schools (from primary schools to universities) and hospitals. Since then, the Catholic Church has founded hundreds of other colleges and universities, along with thousands of primary and secondary schools. Schools like the University of Notre Dame is ranked best in its state (Indiana), as Georgetown University is ranked best in the District of Columbia. The following 10 Catholic universities are also ranked among the top 100 universities in the US: University of Notre Dame, Georgetown University, Boston College, Santa Clara University, Villanova University, Marquette University, Fordham University, Gonzaga University, Loyola Marymount University, and the University of San Diego. [100]

Orthodox Christianity

Eastern Orthodox Christianity was present in North America since the Russian colonization of Alaska; however, Alaska would not become a United States territory until 1867, and most Eastern Orthodox Russian settlers in Alaska returned to Russia after the American acquisition of the Alaskan territory. However the native converts and a few priests remained behind, and Alaska still is represented[clarification needed].

Most Eastern Orthodox Christians arrived in the contiguous United States as immigrants beginning in the late 19th century and throughout the 20th century. Two major groups brought Eastern Orthodoxy to America, one were Eastern Europeans like Russians, Greeks, Ukrainians, Serbians and others. The second major group were from Levant like Lebanese, Syrians, Palestinians and others.

Armenians, Copts and Syriacs, also brought Oriental Orthodoxy to America.[101][102]

Demographics of various Christian groups

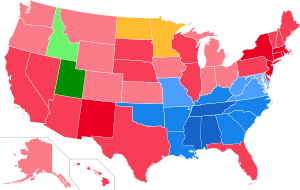

The strength of various sects varies greatly in different regions of the country, with rural parts of the South having many evangelicals but very few Catholics (except Louisiana and the Gulf Coast, and from among the Hispanic community, both of which consist mainly of Catholics), while urbanized areas of the north Atlantic states and Great Lakes, as well as many industrial and mining towns, are heavily Catholic, though still quite mixed, especially due to the heavily Protestant African-American communities. In 1990, nearly 72% of the population of Utah was Mormon, as well as 26% of neighboring Idaho.[103] Lutheranism is most prominent in the Upper Midwest, with North Dakota having the highest percentage of Lutherans (35% according to a 2001 survey).[104]

The largest religion, Christianity, has proportionately diminished since 1990. While the absolute number of Christians rose from 1990 to 2008, the percentage of Christians dropped from 86% to 76%.[105] A nationwide telephone interview of 1,002 adults conducted by The Barna Group found that 70% of American adults believe that God is "the all-powerful, all-knowing creator of the universe who still rules it today", and that 9% of all American adults and 0.5% young adults hold to what the survey defined as a "biblical worldview".[106]

Episcopalian, Presbyterian, Eastern Orthodox and United Church of Christ members[107] have the highest number of graduate and post-graduate degrees per capita of all Christian denominations in the United States,[108][109] as well as the most high-income earners.[110][111] However, owing to the sheer size or demographic head count of Catholics, more individual Catholics have graduate degrees and are in the highest income brackets than have or are individuals of any other religious community.[112]

Other Abrahamic religions

Judaism

After Christianity, Judaism is the next largest religious affiliation in the US, though this identification is not necessarily indicative of religious beliefs or practices.[105] The Jewish population in the United States is approximately 6 million.[113][114] A significant number of people identify themselves as American Jews on ethnic and cultural grounds, rather than religious ones. For example, 19% of self-identified American Jews do not believe God exists.[115] The 2001 ARIS study projected from its sample that there are about 5.3 million adults in the American Jewish population: 2.83 million adults (1.4% of the U.S. adult population) are estimated to be adherents of Judaism; 1.08 million are estimated to be adherents of no religion; and 1.36 million are estimated to be adherents of a religion other than Judaism.[116] ARIS 2008 estimated about 2.68 million adults (1.2%) in the country identify Judaism as their faith.[105] According to a 2017 study, Judaism is the religion of approximately 2% of the American population.[47] According to a 2020 study by the Pew Research Center, the core American Jewish population is estimated at 7.5 million people, this includes 5.8 million Jewish adults.[117] According to study by Steinhardt Social Research Institute, as of 2020, the core American Jewish population is estimated at 7.6 million people, this includes 4.9 million adults who identify their religion as Jewish, 1.2 million Jewish adults who identify with no religion, and 1.6 million Jewish children.[118]

Jews have been present in what is now the US since the 17th century, and specifically allowed since the British colonial Plantation Act 1740. Although small Western European communities initially developed and grew, large-scale immigration did not take place until the late 19th century, largely as a result of persecutions in parts of Eastern Europe. The Jewish community in the United States is composed predominantly of Ashkenazi Jews whose ancestors emigrated from Central and Eastern Europe. There are, however, small numbers of older (and some recently arrived) communities of Sephardi Jews with roots tracing back to 15th century Iberia (Spain, Portugal, and North Africa). There are also Mizrahi Jews (from the Middle East, Caucasia and Central Asia), as well as much smaller numbers of Ethiopian Jews, Indian Jews, and others from various smaller Jewish ethnic divisions. Approximately 25% of the Jewish American population lives in New York City.[119]

According to the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies newsletter published March 2017, based on data from 2010, Jews were the largest minority religion in 231 counties out of the 3143 counties in the country.[57] According to a 2014 survey conducted by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public life, 1.7% of adults in the U.S. identify Judaism as their religion. Among those surveyed, 44% said they were Reform Jews, 22% said they were Conservative Jews, and 14% said they were Orthodox Jews.[120][121] According to the 1990 National Jewish Population Survey, 38% of Jews were affiliated with the Reform tradition, 35% were Conservative, 6% were Orthodox, 1% were Reconstructionists, 10% linked themselves to some other tradition, and 10% said they are "just Jewish".[122]

This way, the American Jews' majority continue to identify themselves with Jewish main traditions, such as Conservative, Orthodox and Reform Judaism.[123][124] But, already in the 1980s, 20–30 percent of members of largest Jewish communities, such as of New York City, Chicago, Miami, and others, rejected a denominational label.[123]

According to the 2001 National Jewish Population Survey, 4.3 million American Jewish adults have some sort of strong connection to the Jewish community, whether religious or cultural.[125] Jewishness is generally considered an ethnic identity as well as a religious one. Among the 4.3 million American Jews described as "strongly connected" to Judaism, over 80% have some sort of active engagement with Judaism, ranging from attendance at daily prayer services on one end of the spectrum to attending Passover Seders or lighting Hanukkah candles on the other. The survey also discovered that Jews in the Northeast and Midwest are generally more observant than Jews in the South or West.

The Jewish American community has higher household incomes than average, and is one of the best educated religious communities in the United States.[107]

Islam

Islam is probably the third largest religion in numbers in the United States, after Christianity and Judaism, followed, according to Gallup, by 0.8% of the population in 2016.[56] Hinduism and Buddhism follow it closely in numbers (in 2014 the large scale Religious Life Survey found Islam with 0.9% and the other two with 0.7% each[107]). According to the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies newsletter published in March 2017, based on data from 2010, Muslims were the largest minority religion in 392 counties out of the 3143 counties in the country.[57] According to the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU) in 2018, there are approximately 3.45 million Muslims living in the United States, with 2.05 million adults, and the rest being children.[126] Across faith groups, ISPU found in 2017 that Muslims were most likely to be born outside of the US (50%), with 36% having undergone naturalization. American Muslims are also America's most diverse religious community with 25% identifying as black or African American, 24% identifying as white, 18% identifying as Asian/Chinese/Japanese, 18% identifying as Arab, and 5% identifying as Hispanic.[127] In addition to diversity, Americans Muslims are most likely to report being low income, and among those who identify as middle class, the majority are Muslim women, not men. Although American Muslim education levels are similar to other religious communities, namely Christians, within the Muslim American population, Muslim women surpass Muslim men in education, with 31% of Muslim women having graduated from a four-year university. 90% of Muslim Americans identify as straight.[127]

Islam in America effectively began with the arrival of African slaves. It is estimated that about 10% of African slaves transported to the United States were Muslim.[128] Most, however, became Christians, and the United States did not have a significant Muslim population until the arrival of immigrants from Arab and East Asian Muslim areas.[129] According to some experts,[130] Islam later gained a higher profile through the Nation of Islam, a religious group that appealed to black Americans after the 1940s; its prominent converts included Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali.[131][132] The first Muslim elected to Congress was Keith Ellison in 2006,[133] followed by André Carson in 2008.[134]

Out of all religious groups surveyed by ISPU, Muslims were found to be the most likely to report experiences of religious discrimination (61%). That can also be broken down when looking at gender (with Muslim women more likely than Muslim men to experience racial discrimination), age (with young people more likely to report experiencing racial discrimination than older people), and race, (with Arab Muslims the most likely to report experiencing religious discrimination). Muslims born in the United States are more likely to experience all three forms of discrimination, gender, religious, and racial.[127]

Research indicates that Muslims in the United States are generally more assimilated and prosperous than their counterparts in Europe.[135][136][137] Like other subcultural and religious communities, the Islamic community has generated its own political organizations and charity organizations.

Bahá'í Faith

The Baháʼí Faith was first mentioned in the United States in 1893 at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago.[138] Soon after, early American converts began embracing the new religion. Thornton Chase was the first American Baháʼí, dating from 1894.[139] One of the first Baháʼí institutions in the U.S. was established in Chicago to facilitate the establishment of the first Baháʼí House of Worship in the West, which was eventually built in Wilmette, Illinois and dedicated in 1953.[140]

Worldwide, the religion has grown faster than the rate of population growth over the 20th century,[141] and has been recognized since the 1980s as the most widespread minority religion in the countries of the world.[142] Similarly, by 2020, the religion was the largest minority religion in about half of the counties.[143] Since about 1970 the state with the single largest Baháʼí population was South Carolina.[144] From 2010 data the largest populations of Baháʼís at the county-by-county level are in Los Angeles, CA, Palm Beach, FL, Harris County, TX, and Cook County, IL.[145] However, estimates of the total number of Baháʼís varies widely from around 175,000[146] to 500,000.[147]

Rastafari

Rastafarians began migrating to the United States in the 1950s, '60s and '70s from the religion's 1930s birthplace, Jamaica.[148][149]

Marcus Garvey, who is considered a prophet by many Rastafarians, rose to prominence and cultivated many of his ideas in the United States.[150][151]

Druze faith

Druze began migrating to the United States in the late 1800s from the Levant (Syria and Lebanon).[152] Druze emigration to the Americas increased at the outset of the 20th century due to the famine during World War I that killed an estimated one third to one half of the population, the 1860 Mount Lebanon civil war, and the Lebanese Civil War between 1975 and 1990.[152] The United States is the second largest home of Druze communities outside the Middle East after Venezuela (60,000).[153] According to some estimates there are about 30,000[154] to 50,000[153] Druzes in the United States, with the largest concentration in Southern California.[154] American Druze are mostly of Lebanese and Syrian descent.[154]

Members of the Druze faith face the difficulty of finding a Druze partner and practicing endogamy; marriage outside the Druze faith is strongly discouraged according to the Druze doctrine. They also face the pressure of keeping the religion alive because many Druze immigrants to the United States converted to Protestantism, becoming communicants of the Presbyterian or Methodist churches.[155][156]

Eastern religions

Hinduism

Hinduism is the fourth largest faith in the United States, representing approximately 1% of the population in 2010s.[47][157] In 2001, there were an estimated 766,000 Hindus in the US, about 0.2% of the total population.[158][159]

The first time Hinduism entered the United States is not clearly identifiable. However, large groups of Hindus have immigrated from India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, other parts of the Caribbean, southern Africa, eastern Africa, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Mauritius, Fiji, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and other regions and countries since the enactment of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. During the 1960s and 1970s Hinduism exercised fascination contributing to the development of New Age thought. During the same decades the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), a Vaishnavite Hindu reform organization, was founded in the US by A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. In 2003, the Hindu American Foundation—a national institution protecting rights of the Hindu community of U.S.—was founded.

According to the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies newsletter published March 2017, based on data from 2010, Hindus were the largest minority religion in 92 counties out of the 3143 counties in the country.[57]

American Hindus have one of the highest rates of educational attainment and household income among all religious communities, and tend to have lower divorce rates.[107] Hindus also have higher acceptance towards homosexuality (71%), which is higher than the general public (62%).[160]

Buddhism

Buddhism entered the US during the 19th century with the arrival of the first immigrants from East Asia. The first Buddhist temple was established in San Francisco in 1853 by Chinese Americans. The first prominent US citizen to publicly convert to Buddhism was Colonel Henry Steel Olcott in 1880 who is still honored in Sri Lanka for his Buddhist revival efforts. An event that contributed to the strengthening of Buddhism in the United States was the Parliament of the World's Religions in 1893, which was attended by many Buddhist delegates sent from India, China, Japan, Vietnam, Thailand and Sri Lanka.

During the late 19th century Buddhist missionaries from Japan traveled to the US. During the same time period, US intellectuals started to take interest in Buddhism.

The early 20th century was characterized by a continuation of tendencies that had their roots in the 19th century. The second half, by contrast, saw the emergence of new approaches, and the move of Buddhism into the mainstream and making itself a mass and social religious phenomenon.[161][162]

According to a 2016 study, Buddhists are approximately 1% of the American population.[47] According to the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies newsletter published March 2017, based on data from 2010, Buddhists were the largest minority religion in 186 counties out of the 3143 counties in the country.[57]

Jainism

Adherents of Jainism first arrived in the United States in the 20th century. The most significant time of Jain immigration was in the early 1970s. The United States has since become a center of the Jain Diaspora. The Federation of Jain Associations in North America is an umbrella organization of local American and Canadian Jain congregations to preserve, practice, and promote Jainism and the Jain way of life.[163]

Sikhism

Sikhism is a religion originating from the Indian subcontinent which was introduced into the United States when, around the turn of the 20th century, Sikhs started emigrating to the United States in significant numbers to work on farms in California. They were the first community to come from India to the US in large numbers.[164] The first Sikh Gurdwara in America was built in Stockton, California, in 1912.[165] In 2007, there were estimated to be between 250,000 and 500,000 Sikhs living in the United States, with the largest populations living on the East and West Coasts, with additional populations in Detroit, Chicago, and Austin.[166][167]

The United States also has a number of non-Punjabi converts to Sikhism.[168]

Taoism

Taoism was popularized throughout the world by the writings and teachings of Laozi and other Taoists as well as the practice of qigong, tai chi, and other Chinese martial arts.[169] The first Taoists in the US were immigrants from China during the mid-nineteenth century. They settled mostly in California where the built the first Taoist temples in the country, including the Tin How Temple in San Francisco's Chinatown and the Joss House in Weaverville. Currently, the Temple of Original Simplicity is located outside of Boston, Massachusetts.

In 2004, there were an estimated 56,000 Taoists in the US.[170]

Other religions

Many other religions are represented in the United States, including Shinto, Caodaism, Thelema, Santería, Kemetism, Neopaganism, Zoroastrianism, Vodou, Druze and many forms of New Age spirituality as well as satirical religions such as Pastafarianism.

Native American religions

Native American religions historically exhibited much diversity, and are often characterized by animism or panentheism.[171][172][173][174] The membership of Native American religions in the 21st century comprises about 9,000 people.[175]

The Native American Church is a religious tradition involving the ceremonial and sacred use of Lophophora williamsii (peyote).[176][177]

Neopaganism

Neopaganism in the United States is represented by widely different movements and organizations. The largest Neopagan religion is Wicca, followed by Neo-Druidism.[178][179] Other neopagan movements include Germanic Neopaganism, Celtic Reconstructionist Paganism, Hellenic Polytheistic Reconstructionism, and Semitic neopaganism.

Druidry

According to the American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS), there are approximately 30,000 druids in the United States.[180] Modern Druidism arrived in North America first in the form of fraternal Druidic organizations in the nineteenth century, and orders such as the Ancient Order of Druids in America were founded as distinct American groups as early as 1912. In 1963, the Reformed Druids of North America (RDNA) was founded by students at Carleton College, Northfield, Minnesota. They adopted elements of Neopaganism into their practices, for instance celebrating the festivals of the Wheel of the Year.[181]

Wicca

Wicca advanced in North America in the 1960s by Raymond Buckland, an expatriate Briton who visited Gardner's Isle of Man coven to gain initiation.[182] Universal Eclectic Wicca was popularized in 1969 for a diverse membership drawing from both Dianic and British Traditional Wiccan backgrounds.[183]

New Thought Movement

A group of churches which started in the 1830s in the United States is known under the banner of "New Thought". These churches share a spiritual, metaphysical and mystical predisposition and understanding of the Bible and were strongly influenced by the Transcendentalist movement, particularly the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Another antecedent of this movement was Swedenborgianism, founded on the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg in 1787.[184] The New Thought concept was named by Emma Curtis Hopkins ("teacher of teachers") after Hopkins broke off from Mary Baker Eddy's Church of Christ, Scientist. The movement had been previously known as the Mental Sciences or the Christian Sciences. The three major branches are Religious Science, Unity Church and Divine Science.

Unitarian Universalism

Unitarian Universalists (UUs) are among the most liberal of all religious denominations in America.[185] The shared creed includes beliefs in inherent dignity, a common search for truth, respect for beliefs of others, compassion, and social action.[186] They are unified by their shared search for spiritual growth and by the understanding that an individual's theology is a result of that search and not obedience to an authoritarian requirement.[187] UUs have historical ties to anti-war, civil rights, and LGBT rights movements,[188] as well as providing inclusive church services for the broad spectrum of liberal Christians, liberal Jews, secular humanists, LGBT, Jewish-Christian parents and partners, Earth-centered/Wicca, and Buddhist meditation adherents.[189] In fact, many UUs also identify as belonging to another religious group, including atheism and agnosticism.[190]

No religion

In 2020, approximately 28% of Americans declared themselves to be not religiously affiliated.[191]

Agnosticism, atheism, and humanism

A 2001 survey directed by Dr. Ariela Keysar for the City University of New York indicated that, amongst the more than 100 categories of response, "no religious identification" had the greatest increase in population in both absolute and percentage terms. This category included atheists, agnostics, humanists, and others with no stated religious preferences. Figures are up from 14.3 million in 1990 to 34.2 million in 2008, representing an increase from 8% of the total population in 1990 to 15% in 2008.[105] A nationwide Pew Research study published in 2008 put the figure of unaffiliated persons at 16.1%,[159] while another Pew study published in 2012 was described as placing the proportion at about 20% overall and roughly 33% for the 18–29-year-old demographic.[192] It is unknown why the number of self-identified "nones" is rising, although it may relate to a general decline of trust in institutions,[27] the September 11 attacks,[193] rise of the religious right,[194] and sexual abuse scandals, particularly those within the Southern Baptist Convention[195] and Catholic Church.[196] The majority of "nones" have religion-like beliefs and believe in some conception of a higher power.[24]

In a 2006 nationwide poll, University of Minnesota researchers found that despite an increasing acceptance of religious diversity, atheists were generally distrusted by other Americans, who trusted them less than Muslims, recent immigrants and other minority groups in "sharing their vision of American society". They also associated atheists with undesirable attributes such as amorality, criminal behavior, rampant materialism and cultural elitism.[197][198] However, the same study also reported that "The researchers also found acceptance or rejection of atheists is related not only to personal religiosity, but also to one's exposure to diversity, education and political orientation – with more educated, East and West Coast Americans more accepting of atheists than their Midwestern counterparts."[199] Some surveys have indicated that doubts about the existence of the divine were growing quickly among Americans under 30.[200]

On March 24, 2012, American atheists sponsored the Reason Rally in Washington, D.C., followed by the American Atheist Convention in Bethesda, Maryland. Organizers called the estimated crowd of 8,000–10,000 the largest-ever US gathering of atheists in one place.[201]

Secular people in the United States, such as atheist and agnostics, have a distinctive secular tradition that can be traced for at least hundreds of years. They sometimes create religion-like institutions and communities, create rituals, and debate aspects of their shared beliefs.[202]

Belief in the existence of a god

Various polls have been conducted to determine Americans' actual beliefs regarding a god:

- A 2021 Pew Research Center Survey found that 91% of American believe in a higher power.[203]

- A 2018 Pew Research Center Survey found that 90% of American believe in a higher power.[204]

- In 2014 the Pew Research Center's Religious Landscape Study showed 63% of Americans believed in God and were "absolutely certain" in their view, while the figure rose to 89% including those who were agnostic.[205]

- A 2012 WIN-Gallup International poll showed that 5% of Americans considered themselves "convinced" atheists, which was a fivefold increase from the last time the survey was taken in 2005, and 5% said they did not know or else did not respond.[206]

- A 2012 Pew Research Center survey found that doubts about the existence of a god had grown among younger Americans, with 68% telling Pew they never doubt God's existence, a 15-point drop in five years. In 2007, 83% of American millennials said they never doubted God's existence.[200][207]

- A 2011 Gallup poll found 92% of Americans said yes to the basic question "Do you believe in God?", while 7% said no and 1% had no opinion.[208]

- A 2010 Gallup poll found 80% of Americans believe in a god, 12% believe in a universal spirit, 6% don't believe in either, 1% chose "other", and 1% had no opinion. 80% is a decrease from the 1940s, when Gallup first asked this question.

- A late 2009 online Harris poll of 2,303 U.S. adults (18 and older)[209] found that "82% of adult Americans believe in God", the same number as in two earlier polls in 2005 and 2007. Another 9% said they did not believe in God, and 9% said that they were not sure. It further concluded, "Large majorities also believe in miracles (76%), heaven (75%), that Jesus is God or the Son of God (73%), in angels (72%), the survival of the soul after death (71%), and in the resurrection of Jesus (70%). Less than half (45%) of adults believe in Darwin's theory of evolution but this is more than the 40% who believe in creationism..... Many people consider themselves Christians without necessarily believing in some of the key beliefs of Christianity. However, this is not true of born-again Christians. In addition to their religious beliefs, large minorities of adults, including many Christians, have "pagan" or pre-Christian beliefs such as a belief in ghosts, astrology, witches and reincarnation.... Because the sample is based on those who agreed to participate in the Harris Interactive panel, no estimates of theoretical sampling error can be calculated."

- A 2008 survey of 1,000 people concluded that, based on their stated beliefs rather than their religious identification, 69.5% of Americans believe in a personal God, roughly 12.3% of Americans are atheist or agnostic, and another 12.1% are deistic (believing in a higher power/non-personal God, but no personal God).[105]

- Mark Chaves, a Duke University professor of sociology, religion and divinity, found that 92% of Americans believed in God in 2008, but that significantly fewer Americans have great confidence in their religious leaders than a generation ago.[210]

- According to a 2008 ARIS survey, belief in God varies considerably by region. The lowest rate is in the West with 59% reporting a belief in God, and the highest rate is in the South at 86%.[211]

Spiritual but not religious

"Spiritual but not religious" (SBNR) is self-identified stance of spirituality that takes issue with organized religion as the sole or most valuable means of furthering spiritual growth. Spirituality places an emphasis upon the wellbeing of the "mind-body-spirit",[212] so holistic activities such as tai chi, reiki, and yoga are common within the SBNR movement.[213] In contrast to religion, spirituality has often been associated with the interior life of the individual.[214]

One fifth of the US public and a third of adults under the age of 30 are reportedly unaffiliated with any religion, however they identify as being spiritual in some way. Of these religiously unaffiliated Americans, 37% classify themselves as spiritual but not religious.[215]

According to some sociologists, perceptions of religious decline are a popular misconception.[53] They state that surveys showing so suffer from methodological deficiencies, that Americans are becoming more religious, and that Atheists and Agnostics make up a small and stable percentage of the population.[216][217] "Religious belief and interest" has remained relatively stable in recent years; "organizational participation", in contrast, has decreased.[218]

Major U.S.-origin movements

Christian

- Adventism — began as an inter-denominational movement. Its most vocal leader was William Miller, who in the 1830s in New York became convinced of an imminent Second Coming of Jesus. The most prominent modern group to emerge from this is the Seventh-day Adventists.[219][220]

- Holiness movement — a movement that emerged chiefly within 19th-century American Methodism with the belief that the Christian life should be free of sin.[221]

- Jehovah's Witnesses — originated with the religious movement known as Bible Students, which was founded in Pennsylvania in the late 1870s by Charles Taze Russell. In their early years, the Bible Students were loosely connected with Adventism, and the Jehovah's Witnesses still share some similarities with it.[220][222]

- Latter Day Saint movement founded in 1830 by Joseph Smith in upstate New York – a product of the Christian revivalist movement of the Second Great Awakening and based in Christian primitivism. Multiple Latter Day Saint denominations can be found throughout the United States. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), the largest denomination, is headquartered in Salt Lake City, Utah, and it has members in many countries. The Community of Christ, the second-largest denomination, is headquartered in Independence, Missouri.[223]

- Pentecostalism and Charismatic movement — a large movement which emphasizes the role of the baptism with the Holy Spirit and the use of spiritual gifts (charismata), finds its historic roots in the Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles from 1904 to 1906, sparked by Charles Parham.[224]

- Universalist Church of America's first regional conference was founded in 1793.[225]

Other

- Eckankar — founded in Las Vegas in 1965 by Paul Twitchell and drawing from the Radha Soami new Indian movement.[226]

- International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) or Hare Krishna movement- founded in 1966 in New York City by A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. It preaches Gaudiya Vaishnavism, a sect of Hinduism[227][228]

- Native American Church – also known as Peyotism and Peyote Religion, founded by Quanah Parker beginning in the 1890s and incorporating in 1918. Today it is the most widespread indigenous religion among Native Americans in the United States (except Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians), with an estimated 250,000 followers.[229]

- New Thought Movement – two of the early proponents of New Thought beliefs during the mid to late 19th century were Phineas Parkhurst Quimby and the Mother of New Thought, Emma Curtis Hopkins. The three major branches are Religious Science, Unity Church and Divine Science.

- Reconstructionist Judaism – founded by Mordecai Kaplan and started in the 1920s.[230]

- Self-Realization Fellowship — a neo-Hindu movement founded in Los Angeles by Paramahansa Yogananda in 1920.

- Theosophy — an influential esoteric religion established during the late 19th century by Helena Blavatsky.[231]

- Unitarian Universalist Association- founded in 1961 from the consolidation of the American Unitarian Association and the Universalist Church of America. Historically Christian denominations, the UUA is no longer Christian and is the largest Unitarian Universalist denomination in the world.

- 3HO – a sect of Sikhism, founded in Los Angeles in 1971 by Yogi Bhajan and followed mostly by White Americans.[232][233][234][235][236]

Statistics

Self-identified religiosity (2023 The Wall Street Journal-NORC poll)[237]

The U.S. Census does not ask about religion. Various groups have conducted surveys to determine approximate percentages of those affiliated with each religious group.

The Association of Religion Data Archives (1900-2050)

| Year | All Christians | Non-Religious | Jewish | Muslim | Buddhists |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 97.0 | 1.3 | 1.4 | ||

| 1950 | 93.1 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 0.1 | |

| 1970 | 91.3 | 5.2 | 2.6 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| 2000 | 82.0 | 12.0 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| 2020 | 74.2 | 19.7 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| 2050(P) | 66.3 | 25.8 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 1.8 |

| Year | Protestant | Independents | Unaffiliated Christian | Catholic | Orthodox |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 48.7 | 8.8 | 24.8 | 14.2 | 0.5 |

| 1950 | 37.0 | 15.1 | 20.1 | 19.2 | 1.7 |

| 1970 | 28.8 | 17.8 | 19.6 | 23.1 | 2.1 |

| 2000 | 21.0 | 20.2 | 16.4 | 22.4 | 2.0 |

| 2020 | 16.3 | 19.3 | 14.1 | 22.3 | 2.2 |

| 2050(P) | 15.8 | 19.1 | 8.0 | 21.1 | 2.3 |

Public Religion Research Institute data (2020)

The Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) has made annual estimates about religious adherence in the United States every year since 2013, and they most recently updated their data in 2020. Their data can be broken down to the state level, and data has also been made available of several large metro areas. Data is collected from roughly 50,000 telephone interviews conducted every year.[239]

Their most recent data shows that approximately 70% of Americans are Christians (down from 71% in 2013), with about 46% of the population professing belief in Protestant Christianity, and another 22% adhering to Catholicism. About 23% of the population adheres to no religion, and 7% more of the population professes a Non-Christian religion (such as Judaism, Islam, or Hinduism).[239][240]

| Religious Affiliation | National % | South % | West % | Midwest % | Northeast % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian | 69.7 | 74 | 65 | 72 | 67 | |

| Protestant | 45.6 | 53 | 36 | 50 | 39 | |

| White Evangelical | 14.5 | 18 | 10 | 18 | 9 | |

| White Mainline Protestant | 16.4 | 17 | 14 | 21 | 15 | |

| Black Protestant | 7.3 | 10 | 3 | 6 | 8 | |

| Hispanic Protestant | 3.9 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 4 | |

| Other non-white Protestant | 3.5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | |

| Catholic | 21.8 | 19 | 24 | 21 | 26 | |

| White Catholic | 11.7 | 9 | 9 | 15 | 16 | |

| Hispanic Catholic | 8.2 | 8 | 13 | 4 | 8 | |

| Other non-white Catholic | 1.9 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Mormon | 1.3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| Jehovah's Witness | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Orthodox Christian | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Unaffiliated | 23.3 | 21 | 27 | 22 | 24 | |

| Non-Christian | 7.0 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 9 | |

| Jewish | 1.4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| Muslim | 0.8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Buddhist | 0.8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Hindu | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Other non-Christian | 3.5 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

2014 Pew Research Center data

Protestantism

| Affiliation | % of U.S. population | |

|---|---|---|

| Christian | 70.6 | |

| Protestant | 46.5 | |

| Evangelical Protestant | 25.4 | |

| Mainline Protestant | 14.7 | |

| Black church | 6.5 | |

| Catholic | 20.8 | |

| Mormon | 1.6 | |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 0.8 | |

| Eastern Orthodox | 0.5 | |

| Other Christian | 0.4 | |

| Unaffiliated | 22.8 | |

| Nothing in particular | 15.8 | |

| Agnostic | 4.0 | |

| Atheist | 3.1 | |

| Non-Christian | 5.9 | |

| Jewish | 1.9 | |

| Muslim | 0.9 | |

| Buddhist | 0.7 | |

| Hindu | 0.7 | |

| Other non-Christian | 1.8 | |

| Don't know/refused answer | 0.6 | |

| Total | 100 | |

2010 ASARB data

The Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies (ASARB) surveyed congregations for their memberships. Churches were asked for their membership numbers. Adjustments were made for those congregations that did not respond and for religious groups that reported only adult membership.[241] ASARB estimates that most of the churches not responding were black Protestant congregations. Significant difference in results from other databases include the lower representation of adherents of (1) all kinds (62.7%), (2) Christians (59.9%), (3) Protestants (less than 36%); and the greater number of unaffiliated (37.3%).

| Major | >10% | >20% | |

| Catholic | |||

| Baptist | |||

| Lutheran | |||

| Methodist | |||

| No religion | |||

| Mormonism | |||

| Protestant | |||

| Pentecostal | |||

| Christian (unspecified/other) |

| <20% | <30% | <40% | <50% | >50% | |

| Baptist | |||||

| Catholic | |||||

| Mormon | |||||

| Lutheran |

| Religious group | Number in year 2010 |

% in year 2010 |

|---|---|---|

| Total US pop year 2010 | 308,745,538 | 100.0% |

| Evangelical Protestant | 50,013,107 | 16.2% |

| Mainline Protestant | 22,568,258 | 7.3% |

| Black Protestant | 4,877,067 | 1.6% |

| Protestant total | 77,458,432 | 25.1% |

| Catholic | 58,934,906 | 19.1% |

| Orthodox | 1,056,535 | 0.3% |

| adherents (unadjusted) | 150,596,792 | 48.8% |

| unclaimed | 158,148,746 | 51.2% |

| other – including Mormon & Christ Scientist | 13,146,919 | 4.3% |

| The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Mormon, LDS) | 6,144,582 | 2.0% |

| other – excluding Mormon | 7,002,337 | 2.3% |

| Jewish estimate | 6,141,325 | 2.0% |

| Buddhist estimate | 2,000,000 | 0.7% |

| Muslim estimate | 2,600,082 | 0.8% |

| Hindu estimate | 400,000 | 0.4% |

| Source: ASARB[114][242] | ||

Ethnicity

The table below shows the religious affiliations among the ethnicities in the United States, according to the Pew Forum 2014 survey.[120] People of Black ethnicity were most likely to be part of a formal religion, with 80% percent being Christians. Protestant denominations make up the majority of the Christians in the ethnicities.

| Religion | Non-Hispanic White (62%) |

Black (13%) | Hispanic (17%) | Other/mixed (8%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian | 70% | 79% | 77% | 49% |

| Protestant | 48% | 71% | 26% | 33% |

| Catholic | 19% | 5% | 48% | 13% |

| Mormon | 2% | <0.5% | 1% | 1% |

| Jehovah's Witness | <0.5% | 2% | 1% | 1% |

| Orthodox | 1% | <0.5% | <0.5% | 1% |

| Other | <0.5% | 1% | <0.5% | 1% |

| Non-Christian faiths | 5% | 3% | 2% | 21% |

| Jewish | 3% | <0.5% | 1% | 1% |

| Muslim | <0.5% | 2% | <0.5% | 3% |

| Buddhist | <0.5% | <0.5% | 1% | 4% |

| Hindu | <0.5% | <0.5% | <0.5% | 8% |

| Other world religions | <0.5% | <0.5% | <0.5% | 2% |

| Other faiths | 2% | 1% | 1% | 2% |

| Unaffiliated (including atheist and agnostic) | 24% | 18% | 20% | 29% |

ARIS findings regarding self-identification

The United States government does not collect religious data in its census. The survey below, the American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS) of 2008, was a random digit-dialed telephone survey of 54,461 American residential households in the contiguous United States. The 1990 sample size was 113,723; 2001 sample size was 50,281.

Adult respondents were asked the open-ended question, "What is your religion, if any?" Interviewers did not prompt or offer a suggested list of potential answers. The religion of the spouse or partner was also asked. If the initial answer was "Protestant" or "Christian" further questions were asked to probe which particular denomination. About one third of the sample was asked more detailed demographic questions.

Religious Self-Identification of the U.S. Adult Population: 1990, 2001, 2008[105]

Figures are not adjusted for refusals to reply; investigators suspect refusals are possibly more representative of "no religion" than any other group.

| Group |

1990 adults x 1,000 |

2001 adults x 1,000 |

2008 adults x 1,000 |

Numerical Change 1990– 2008 as % of 1990 |

1990 % of adults |

2001 % of adults |

2008 % of adults |

change in % of total adults 1990– 2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult population, total | 175,440 | 207,983 | 228,182 | 30.1% | ||||

| Adult population, responded | 171,409 | 196,683 | 216,367 | 26.2% | 97.7% | 94.6% | 94.8% | −2.9% |

| Total Christian | 151,225 | 159,514 | 173,402 | 14.7% | 86.2% | 76.7% | 76.0% | −10.2% |

| Catholic | 46,004 | 50,873 | 57,199 | 24.3% | 26.2% | 24.5% | 25.1% | −1.2% |

| non-Catholic Christian | 105,221 | 108,641 | 116,203 | 10.4% | 60.0% | 52.2% | 50.9% | −9.0% |

| Baptist | 33,964 | 33,820 | 36,148 | 6.4% | 19.4% | 16.3% | 15.8% | −3.5% |

| Mainline Christian | 32,784 | 35,788 | 29,375 | −10.4% | 18.7% | 17.2% | 12.9% | −5.8% |

| Methodist | 14,174 | 14,039 | 11,366 | −19.8% | 8.1% | 6.8% | 5.0% | −3.1% |

| Lutheran | 9,110 | 9,580 | 8,674 | −4.8% | 5.2% | 4.6% | 3.8% | −1.4% |

| Presbyterian | 4,985 | 5,596 | 4,723 | −5.3% | 2.8% | 2.7% | 2.1% | −0.8% |

| Episcopal/Anglican | 3,043 | 3,451 | 2,405 | −21.0% | 1.7% | 1.7% | 1.1% | −0.7% |

| United Church of Christ | 438 | 1,378 | 736 | 68.0% | 0.2% | 0.7% | 0.3% | 0.1% |

| Christian Generic | 25,980 | 22,546 | 32,441 | 24.9% | 14.8% | 10.8% | 14.2% | −0.6% |

| Christian Unspecified | 8,073 | 14,190 | 16,384 | 102.9% | 4.6% | 6.8% | 7.2% | 2.6% |

| Non-denominational Christian | 194 | 2,489 | 8,032 | 4040.2% | 0.1% | 1.2% | 3.5% | 3.4% |

| Protestant – Unspecified | 17,214 | 4,647 | 5,187 | −69.9% | 9.8% | 2.2% | 2.3% | −7.5% |

| Evangelical/Born Again | 546 | 1,088 | 2,154 | 294.5% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.9% | 0.6% |

| Pentecostal/Charismatic | 5,647 | 7,831 | 7,948 | 40.7% | 3.2% | 3.8% | 3.5% | 0.3% |

| Pentecostal – Unspecified | 3,116 | 4,407 | 5,416 | 73.8% | 1.8% | 2.1% | 2.4% | 0.6% |

| Assemblies of God | 617 | 1,105 | 810 | 31.3% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.0% |

| Church of God | 590 | 943 | 663 | 12.4% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.0% |

| Other Protestant Denominations | 4,630 | 5,949 | 7,131 | 54.0% | 2.6% | 2.9% | 3.1% | 0.5% |

| Churches of Christ | 1,769 | 2,593 | 1,921 | 8.6% | 1.0% | 1.2% | 0.8% | −0.2% |

| Jehovah's Witness | 1,381 | 1,331 | 1,914 | 38.6% | 0.8% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 0.1% |

| Seventh-Day Adventist | 668 | 724 | 938 | 40.4% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.0% |

| Mormon/Latter Day Saints | 2,487 | 2,697 | 3,158 | 27.0% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 0.0% |

| Total non-Christian religions | 5,853 | 7,740 | 8,796 | 50.3% | 3.3% | 3.7% | 3.9% | 0.5% |

| Jewish | 3,137 | 2,837 | 2,680 | −14.6% | 1.8% | 1.4% | 1.2% | −0.6% |

| Eastern Religions | 687 | 2,020 | 1,961 | 185.4% | 0.4% | 1.0% | 0.9% | 0.5% |

| Buddhist | 404 | 1,082 | 1,189 | 194.3% | 0.2% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.3% |

| Muslim | 527 | 1,104 | 1,349 | 156.0% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.3% |

| New Religious Movements & Others | 1,296 | 1,770 | 2,804 | 116.4% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 1.2% | 0.5% |

| None/No religion, total | 14,331 | 29,481 | 34,169 | 138.4% | 8.2% | 14.2% | 15.0% | 6.8% |

| Agnostic+Atheist | 1,186 | 1,893 | 3,606 | 204.0% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 1.6% | 0.9% |

| Did Not Know/Refused to reply | 4,031 | 11,300 | 11,815 | 193.1% | 2.3% | 5.4% | 5.2% | 2.9% |

Highlights:[105]

- The ARIS 2008 survey was carried out during February–November 2008 and collected answers from 54,461 respondents who were questioned in English or Spanish.

- The American population self-identifies as predominantly Christian, but Americans are slowly becoming less Christian.

- 86% of American adults identified as Christians in 1990 and 76% in 2008.

- The historic mainline churches and denominations have experienced the steepest declines, while the non-denominational Christian identity has been trending upward, particularly since 2001.

- The challenge to Christianity in the U.S. does not come from other religions but rather from a rejection of all forms of organized religion.

- 34% of American adults considered themselves "Born Again or Evangelical Christians" in 2008.

- The U.S. population continues to show signs of becoming less religious, with one out of every seven Americans failing to indicate a religious identity in 2008.

- The "Nones" (no stated religious preference, atheist, or agnostic) continue to grow, though at a much slower pace than in the 1990s, from 8.2% in 1990, to 14.1% in 2001, to 15.0% in 2008.

- Asian Americans are substantially more likely to indicate no religious identity than other racial or ethnic groups.

- One sign of the lack of attachment of Americans to religion is that 27% do not expect a religious funeral at their death.

- Based on their stated beliefs rather than their religious identification in 2008, 70% of Americans believe in a personal God, roughly 12% of Americans are atheist (no God) or agnostic (unknowable or unsure), and another 12% are deistic (a higher power but no personal God).

- America's religious geography has been transformed since 1990. Religious switching along with Hispanic immigration has significantly changed the religious profile of some states and regions. Between 1990 and 2008, the Catholic population proportion of the New England states fell from 50% to 36% and in New York fell from 44% to 37%, while it rose in California from 29% to 37% and in Texas from 23% to 32%.

- Overall the 1990–2008 ARIS time series shows that changes in religious self-identification in the first decade of the 21st century have been moderate in comparison to the 1990s, which was a period of significant shifts in the religious composition of the United States.

Attendance

Gallup survey data found that 73% of Americans were members of a church, synagogue or mosque in 1937, peaking at 76% shortly after World War II, before trending slightly downward to 70% by 2000. The percentage declined steadily during the first two decades of the 21st century, reaching 47% in 2020. Gallup attributed the decline to increasing numbers of Americans expressing no religious preference.[243][244]

A 2013 Public Religion Research Institute survey reported that 31% of Americans attend religious services at least weekly.[245] According to a 2022 Gallup poll, 75% of Americans report praying often or sometimes and religion plays a very (46%) or fairly (26%) important role in their lives.[246]

In a 2009 Gallup survey, 41.6%[247] of American residents stated that they attended a church, synagogue, or mosque once a week or almost every week. This percentage is higher than other surveyed Western countries.[248][249] Church attendance varies considerably by state and region. The figures, updated to 2014, ranged from 51% in Utah to 17% in Vermont.

When it comes to mosque attendance specifically, data collected by a 2017 poll by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU) shows that American Muslim women and men attend the mosque at similar rates (45% for men and 35% for women).[127] Additionally, when compared to the general public looking at the attendance of religious services, young Muslim Americans attend the mosque at closer rates to older Muslim Americans. Muslim Americans who regularly attend mosques are more likely to work with their neighbors to solve community problems (49 vs. 30 percent), be registered to vote (74 vs. 49 percent), and plan to vote (92 vs. 81 percent). Overall, "there is no correlation between Muslim attitudes toward violence and their frequency of mosque attendance".[127]

Religion and politics

In August 2010, 67% of Americans said religion was losing influence, compared with 59% who said this in 2006. Majorities of white evangelical Protestants (79%), white mainline Protestants (67%), black Protestants (56%), Catholics (71%), and the religiously unaffiliated (62%) all agreed that religion was losing influence on American life; 53% of the total public said this was a bad thing, while just 10% see it as a good thing.[250]

Politicians frequently discuss their religion when campaigning, and fundamentalists and black Protestants are highly politically active. However, to keep their status as tax-exempt organizations they must not officially endorse a candidate. Historically Catholics were heavily Democratic before the 1970s, while mainline Protestants comprised the core of the Republican Party. Those patterns have faded away—Catholics, for example, now split about 50–50. However, white evangelicals since 1980 have made up a solidly Republican group that favors conservative candidates. Secular voters are increasingly Democratic.[251]

Only four presidential candidates for major parties have been Catholics, all for the Democratic party:

- Alfred E. Smith in presidential election of 1928 was subjected to anti-Catholic rhetoric, which seriously hurt him in the Baptist areas of the South and Lutheran areas of the Midwest, but he did well in the Catholic urban strongholds of the Northeast.

- John F. Kennedy secured the Democratic presidential nomination in 1960. In the 1960 election, Kennedy faced accusations that as a Catholic president he would do as the Pope would tell him to do, a charge that Kennedy refuted in a famous address to Protestant ministers.

- John Kerry, a Catholic, won the Democratic presidential nomination in 2004. In the 2004 election religion was hardly an issue, and most Catholics voted for his Protestant opponent George W. Bush.[252]

- Joe Biden, a Catholic, won the Democratic presidential nomination in 2020, and then won the 2020 presidential election, becoming the second Catholic president, after John F. Kennedy.[253] Biden was also the first Catholic vice president.[254]

Joe Lieberman was the first major presidential candidate that was Jewish, on the Gore–Lieberman campaign of 2000 (although John Kerry and Barry Goldwater both had Jewish ancestry, they were practicing Christians). Bernie Sanders ran against Hillary Clinton in the Democratic primary of 2016. He was the first major Jewish candidate to compete in the presidential primary process. However, Sanders noted during the campaign that he does not actively practice any religion.[255]

In 2006 Keith Ellison of Minnesota became the first Muslim elected to Congress; when re-enacting his swearing-in for photos, he used the copy of the Qur'an once owned by Thomas Jefferson.[256] André Carson is the second Muslim to serve in Congress.

A Gallup poll released in 2007[257] indicated that 53% of Americans would refuse to vote for an atheist as president, up from 48% in 1987 and 1999. But then the number started to drop again and reached record low 43% in 2012 and 40% in 2015.[258][259]

Mitt Romney, the Republican presidential nominee in 2012, is Mormon and a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He is the former governor of the state of Massachusetts, and his father George Romney was the governor of the state of Michigan.

On January 3, 2013, Tulsi Gabbard became the first Hindu member of Congress, using a copy of the Bhagavad Gita while swearing-in.[260]

By age

Self-identified religious affiliation among 18-29 year olds (Spring 2023 Harvard Youth Poll)[261]

Theism, religion, morality, and politics

Pew Research Center

The Pew Research Center has routinely conducted surveys surrounding theism, religion, and morality since 2002, asking:[262]

Which of the following statements comes closest to your opinion?

And whether they feel like:[262]

[Option #1:] It is not necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values.

Or:

[Option #2:] It is necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values.

Online survey trends: Is it necessary to believe in God to be a good person?[262]

| Polling Date | Necessary | Not necessary | Unsure/Refused/Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spring 2022 | 34 | 65 | 1 |

| January 2020 | 35 | 65 | 1 |

| September 2019 | 36 | 63 | 1 |

| December 2017 | 33 | 66 | >0 |

| July 2014 | 44 | 55 | 1 |

Telephone trends: Is it necessary to believe in God to be a good person?[262]

| Is it necessary to believe in God to be a good person? | Necessary | Not necessary | Don't Know/Unsure/other |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spring 2019 | 44 | 54 | 2 |

| Spring 2011 | 53 | 46 | 2 |

| Spring 2007 | 57 | 41 | 2 |

| Summer 2002 | 58 | 40 | 2 |

YouGov America

Is it necessary to believe in God to be a good person?[263]

| Survey Polling Date | Necessary | Not Necessary | Don't Know/Unsure/Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| November 17–21, 2022 | 32 | 53 | 15 |

Effect of churches and religious organizations on morality:[263]

| Survey Polling Date | Strengthen morality in society | Don't make much difference to morality in society | Don't Know | Weaken morality in society |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| November 17–21, 2022 | 47 | 26 | 14 | 13 |

See also

- American civil religion

- Christianity in the United States

- Confucianism in the United States

- Church property disputes in the United States

- Freedom of religion in the United States

- Historical religious demographics of the United States

- List of religious movements that began in the United States

- List of U.S. states and territories by religiosity

- Protestantism in the United States

- Relationship between religion and science

- Religion in United States prisons

- School prayer in the United States

- Separation of church and state in the United States

- Televangelism

References

- ^ Staff (June 8, 2007). "In Depth: Topics A to Z (Religion)". Gallup, Inc. Retrieved November 1, 2023.

- ^ a b Fahmy, Dalia (July 31, 2018). "Americans are far more religious than adults in other wealthy nations". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on January 9, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

American adults under the age of 40 are less likely to pray than their elders, less likely to attend church services and less likely to identify with any religion – all of which may portend future declines in levels of religious commitment

- ^ Mitchell, Travis (November 23, 2021). "Few Americans Blame God or Say Faith Has Been Shaken Amid Pandemic, Other Tragedies". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project.

The combined nine-in-ten Americans who believe in God or a higher power (91%) were asked a series of follow-up questions about the relationship between God and human suffering.

- ^ Froese, Paul; Uecker, Jeremy E. (September 2022). "Prayer in America: A Detailed Analysis of the Various Dimensions of Prayer". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 61 (3–4): 663–689. doi:10.1111/jssr.12810. ISSN 0021-8294. S2CID 253439298.

- ^ Chaves, Mark (2017). American Religion: Contemporary Trends. Princeton, NJ; London: Princeton University Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 9780691177564.

The vast majority of people — approximately 80 percent — describe themselves as both spiritual and religious. Still, a small but growing minority of Americans describe themselves as spiritual but not religious, as figure 3.4 shows. In 1998, 9 percent of Americans described themselves as at least moderately spiritual but not more than slightly religious. That number rose to 16 percent in the 2010s.

- ^ Pearce, Lisa D.; Gilliland, Claire C. (2020). Religion in America. Sociology in the Twenty-First Century, 6. Oakland, Ca: University of California Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780520296411.

Most people in the United States, however, identify as spiritual and religious.

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon (2012) [2003]. Protestant Faith in America (2nd ed.). New York: Chelsea House/Facts On File. ISBN 978-1-4381-4039-1.

- ^ Pearce, Lisa D.; Gilliland, Claire C. (2020). Religion in America. Sociology in the Twenty-First Century, 6. Oakland, Ca: University of California Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9780520296411.

- ^ a b Holifield, E. Brooks (2015). Why Are Americans So Religious? The Limitations of Market Explanations. Religion and the Marketplace in the United States. pp. 33–60. ISBN 9780199361809.

- ^ Donadio, Rachel (November 22, 2021). "Why Is France So Afraid of God?". The Atlantic. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon; et al., eds. (2009) [1978]. Melton's Encyclopedia of American Religions (8th ed.). Detroit, Mi: Gale Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-787-69696-2.

- ^ Pasquier, Michael (2023) [2016]. Religion in America: The Basics (2nd ed.). London; New York: Routledge. pp. 6–7. ISBN 9780367691806.

- ^ a b c Sullivan, Andrew (September 14, 2018). "The American Past: A History of Contradictions". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Finke, Roger; Stark, Rodney (2006). The Churching of America, 1776–2005: Winners and Losers in our Religious Economy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. pp. 22, 23. ISBN 978-0813535531.

- ^ Edwards, Mark (July 2, 2015). "Was America founded as a Christian nation?". CNN. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

Only after the violent attacks on religion in the French Revolution did alarm about the low level of religion in America escalate and enthusiasm for religion catch fire.

- ^ Conroy-Krutz, Emily (June 7, 2013). "Religion and Reform". The American Yawp. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ "The American Religious Landscape in 2020s". Public Religion Research Institute. July 8, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "In U.S., Decline of Christianity Continues at Rapid Pace" Archived October 3, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Pew Research Center, October 17, 2019, Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ Newport, Frank (February 4, 2016). "New Hampshire Now Least Religious State in U.S." Gallup. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- ^ Giatti, Ian M.; Reporter, Christian Post (January 6, 2023). "Christians continue to dominate Congress even as fewer Americans identify as religious: survey". The Christian Post. Retrieved September 20, 2023.