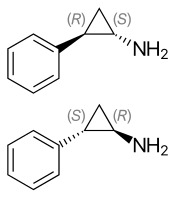

(1S,2R)-(−)-tranylcypromine (top), (1R,2S)-(+)-tranylcypromine (bottom) | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Parnate, many generics[1] |

| Other names | trans-2-phenylcyclopropylamine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682088 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 50%[4] |

| Metabolism | Liver[5][6] |

| Elimination half-life | 2.5 hours[4] |

| Excretion | Urine, Feces[4] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.312 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H11N |

| Molar mass | 133.194 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| | |

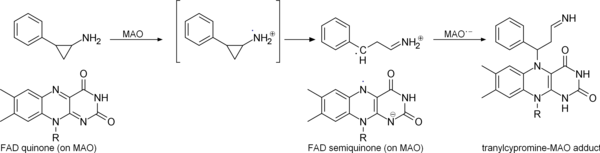

Tranylcypromine, sold under the brand name Parnate among others,[1] is a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI).[4][7] More specifically, tranylcypromine acts as nonselective and irreversible inhibitor of the enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAO).[4][7] It is used as an antidepressant and anxiolytic agent in the clinical treatment of mood and anxiety disorders, respectively. It is also effective in the treatment of ADHD.[8][9]

Tranylcypromine is a cyclopropylamine formed pro forma from the cyclization of amphetamine's side chain; therefore, it is classified as a substituted amphetamine.

Medical uses

[edit]Tranylcypromine is used to treat major depressive disorder, including atypical depression, especially when there is an anxiety component, typically as a second-line treatment.[10] It is also used in depression that is not responsive to reuptake inhibitor antidepressants, such as the SSRIs, TCAs, or bupropion.[11] In addition to being a recognized treatment for major depressive disorder, tranylcypromine has been demonstrated to be effective in treating obsessive compulsive disorder[12][13][14] and panic disorder.[15][16]

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have reported that tranylcypromine is significantly more effective in the treatment of depression than placebo and has efficacy over placebo similar to that of other antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants.[17][18]

Contraindications

[edit]Contraindications include:[10][11][19]

- Porphyria

- Cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease

- Pheochromocytoma

- Tyramine, found in several foods, is metabolized by MAO. Ingestion and absorption of tyramine causes extensive release of norepinephrine, which can rapidly increase blood pressure to the point of causing hypertensive crisis.

- Concomitant use of serotonin-enhancing drugs, including SSRIs, serotonergic TCAs, dextromethorphan, and meperidine may cause serotonin syndrome.

- Concomitant use of MRAs, including fenfluramine, amphetamine, and pseudoephedrine may cause toxicity via serotonin syndrome or hypertensive crisis.

- L-DOPA given without carbidopa may cause hypertensive crisis.

Dietary restrictions

[edit]Tyramine is a biogenic amine produced as a (generally undesirable) byproduct during the fermentation of certain tyrosine-rich foods. It is rapidly metabolized by MAO-A in those not taking MAO-inhibiting drugs. Individuals sensitive to tyramine-induced hypertension may experience an uncomfortable, yet fleeting, increase in blood pressure after ingesting relatively small amounts of tyramine. [20][19][21]

Advances in food safety standards in most nations, as well as the widespread use of starter-cultures shown to result in undetectable to low levels of tyramine in fermented products has rendered concerns of serious hypertensive crises rare in those consuming a modern diet.[22][21] Those treated with MAOIs should still exercise caution, particularly at home, if it is unclear whether food has been properly refrigerated. Since tyramine-producing microbes also produce compounds to which humans have a natural aversion, disposal of any questionable food—particularly meats—should be sufficient to avoid hypertensive crises.

Adverse effects

[edit]Incidence of adverse effects[17]

Very common (>10% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Dizziness secondary to orthostatic hypotension (17%)

Common (1-10% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Tachycardia (5–10%)

- Hypomania (7%)

- Paresthesia (5%)

- Weight loss (2%)

- Confusion (2%)

- Dry mouth (2%)

- Sexual function disorders (2%)

- Hypertension (1–2 hours after ingestion) (2%)

- Rash (2%)

- Urinary retention (2%)

Other (unknown incidence) adverse effects include:

- Increased/decreased appetite

- Blood dyscrasias

- Chest pain

- Diarrhea

- Edema

- Hallucinations

- Hyperreflexia

- Insomnia

- Jaundice

- Leg cramps

- Myalgia

- Palpitations

- Sensation of cold

- Suicidal ideation

- Tremor

Of note, there has not been found to be a correlation between sex and age below 65 regarding incidence of adverse effects.[17]

Tranylcypromine is not associated with weight gain and has a low risk for hepatotoxicity compared to the hydrazine MAOIs.[17][11]

It is generally recommended that MAOIs be discontinued prior to anesthesia; however, this creates a risk of recurrent depression. In a retrospective observational cohort study, patients on tranylcypromine undergoing general anesthesia had a lower incidence of intraoperative hypotension, while there was no difference between patients not taking an MAOI regarding intraoperative incidence of bradycardia, tachycardia, or hypertension.[23] The use of indirect sympathomimetic drugs or drugs affecting serotonin reuptake, such as meperidine or dextromethorphan poses a risk for hypertension and serotonin syndrome respectively; alternative agents are recommended.[24][25] Other studies have come to similar conclusions.[17] Pharmacokinetic interactions with anesthetics are unlikely, given that tranylcypromine is a high-affinity substrate for CYP2A6 and does not inhibit CYP enzymes at therapeutic concentrations.[20]

Tranylcypromine abuse has been reported at doses ranging from 120 to 600 mg per day.[10][26][17] It is thought that higher doses have more amphetamine-like effects and abuse is promoted by the fast onset and short half-life of tranylcypromine.[17]

Cases of suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviours have been reported during tranylcypromine therapy or early after treatment discontinuation.[10]

Symptoms of tranylcypromine overdose are generally more intense manifestations of its usual effects.[10]

Interactions

[edit]In addition to contraindicated concomitant medications, tranylcypromine inhibits CYP2A6, which may reduce the metabolism and increase the toxicity of substrates of this enzyme, such as:[19]

- Dexmedetomidine

- nicotine

- TSNAs (found in cured tobacco products, including cigarettes)

- Valproate

Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors prevent neuronal uptake of tyramine and may reduce its pressor effects.[19]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Tranylcypromine acts as a nonselective and irreversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase.[4] Regarding the isoforms of monoamine oxidase, it shows slight preference for the MAOB isoenzyme over MAOA.[20] This leads to an increase in the availability of monoamines, such as serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, epinephrine as well as a marked increase in the availability of trace amines, such as tryptamine, octopamine, and phenethylamine.[20][19] The clinical relevance of increased trace amine availability is unclear.

It may also act as a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor at higher therapeutic doses.[20] Compared to amphetamine, tranylcypromine shows low potency as a dopamine releasing agent, with even weaker potency for norepinephrine and serotonin release.[20][19]

Tranylcypromine has also been shown to inhibit the histone demethylase, BHC110/LSD1. Tranylcypromine inhibits this enzyme with an IC50 < 2 μM, thus acting as a small molecule inhibitor of histone demethylation with an effect to derepress the transcriptional activity of BHC110/LSD1 target genes.[27] The clinical relevance of this effect is unknown.

Tranylcypromine has been found to inhibit CYP46A1 at nanomolar concentrations.[28] The clinical relevance of this effect is unknown.

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Tranylcypromine reaches its maximum concentration (tmax) within 1–2 hours.[20] After a 20 mg dose, plasma concentrations reach at most 50-200 ng/mL.[20] While its half-life is only about 2 hours, its pharmacodynamic effects last several days to weeks due to irreversible inhibition of MAO.[20]

Metabolites of tranylcypromine include 4-hydroxytranylcypromine, N-acetyltranylcypromine, and N-acetyl-4-hydroxytranylcypromine, which are less potent MAO inhibitors than tranylcypromine itself.[20] Amphetamine was once thought to be a metabolite of tranylcypromine, but has not been shown to be.[20][30][19]

Tranylcypromine inhibits CYP2A6 at therapeutic concentrations.[19]

Chemistry

[edit]

Synthesis

[edit]

History

[edit]Tranylcypromine was originally developed as an analog of amphetamine.[4][20] Although it was first synthesized in 1948,[32] its MAOI action was not discovered until 1959. Precisely because tranylcypromine was not, like isoniazid and iproniazid, a hydrazine derivative, its clinical interest increased enormously, as it was thought it might have a more acceptable therapeutic index than previous MAOIs.[33]

The drug was introduced by Smith, Kline and French in the United Kingdom in 1960, and approved in the United States in 1961.[34] It was withdrawn from the market in February 1964 due to a number of patient deaths involving hypertensive crises with intracranial bleeding. However, it was reintroduced later that year with more limited indications and specific warnings of the risks.[35][20][19]

Research

[edit]Tranylcypromine is known to inhibit LSD1, an enzyme that selectively demethylates two lysines found on histone H3.[27][20][36] Genes promoted downstream of LSD1 are involved in cancer cell growth and metastasis, and several tumor cells express high levels of LSD1.[36] Tranylcypromine analogues with more potent and selective LSD1 inhibitory activity are being researched in the potential treatment of cancers.[36][37]

Tranylcypromine may have neuroprotective properties applicable to the treatment of Parkinson's disease, similar to the MAO-B inhibitors selegiline and rasagiline.[38][11] As of 2017, only one clinical trial in Parkinsonian patients has been conducted, which found some improvement initially and only slight worsening of symptoms after a 1.5 year followup.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "International brands for Tranylcypromine". Drugs.com. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g Williams DA (2007). "Antidepressants". In Foye WO, Lemke TL, Williams DA (eds.). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Hagerstwon, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 590–1. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5.

- ^ "Tranylcypromine". www.drugbank.ca. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- ^ Baker GB, Urichuk LJ, McKenna KF, Kennedy SH (June 1999). "Metabolism of monoamine oxidase inhibitors". Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 19 (3): 411–26. doi:10.1023/a:1006901900106. PMID 10319194. S2CID 21380176.

- ^ a b Baldessarini RJ (2005). "17. Drug therapy of depression and anxiety disorders". In Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-142280-2.

- ^ Zametkin A, Rapoport JL, Murphy DL, Linnoila M, Ismond D. Treatment of hyperactive children with monoamine oxidase inhibitors. I. Clinical efficacy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985 Oct;42(10):962-6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790330042005. PMID: 3899047.

- ^ Levin GM. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: the pharmacist's role. Am Pharm. 1995 Nov;NS35(11):10-20. PMID: 8533716.

- ^ a b c d e "Tranylcypromine". UK Electronic medicines compendium. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Riederer P, Laux G (March 2011). "MAO-inhibitors in Parkinson's Disease". Experimental Neurobiology. 20 (1): 1–17. doi:10.5607/en.2011.20.1.1. PMC 3213739. PMID 22110357.

- ^ Jenike MA (September 1981). "Rapid response of severe obsessive-compulsive disorder to tranylcypromine". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 138 (9): 1249–1250. doi:10.1176/ajp.138.9.1249. PMID 7270737.

- ^ Marques C, Nardi AE, Mendlowicz M, Figueira I, Andrade Y, Camisão C, et al. (1994). "A tranilcipromina no tratamento do transtorno obsessivoðcompulsivo: relato de seis casos" [The tranylcypromine in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: Report of six cases]. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria (in Brazilian Portuguese). pp. 400–403.

- ^ Joffe RT, Swinson RP (1990). "Tranylcypromine in primary obsessive-compulsive disorder". Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 4 (4): 365–367. doi:10.1016/0887-6185(90)90033-6.

- ^ Nardi AE, Lopes FL, Valença AM, Freire RC, Nascimento I, Veras AB, et al. (February 2010). "Double-blind comparison of 30 and 60 mg tranylcypromine daily in patients with panic disorder comorbid with social anxiety disorder". Psychiatry Research. 175 (3): 260–265. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2008.06.025. PMID 20036427. S2CID 45566164.

- ^ Saeed SA, Bruce TJ (May 1998). "Panic disorder: effective treatment options". American Family Physician. 57 (10): 2405–2412. PMID 9614411.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ricken R, Ulrich S, Schlattmann P, Adli M (August 2017). "Tranylcypromine in mind (Part II): Review of clinical pharmacology and meta-analysis of controlled studies in depression". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 27 (8): 714–731. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.04.003. PMID 28579071. S2CID 30987747.

- ^ Ulrich S, Ricken R, Buspavanich P, Schlattmann P, Adli M (2020). "Efficacy and Adverse Effects of Tranylcypromine and Tricyclic Antidepressants in the Treatment of Depression: A Systematic Review and Comprehensive Meta-analysis". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 40 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000001153. PMID 31834088. S2CID 209343653.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gillman PK (February 2011). "Advances pertaining to the pharmacology and interactions of irreversible nonselective monoamine oxidase inhibitors". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 31 (1): 66–74. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e31820469ea. PMID 21192146. S2CID 10525989.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Ulrich S, Ricken R, Adli M (August 2017). "Tranylcypromine in mind (Part I): Review of pharmacology". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 27 (8): 697–713. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.05.007. PMID 28655495. S2CID 4913721.

- ^ a b Kim MJ, Kim KS (2014). "Tyramine production among lactic acid bacteria and other species isolated from kimchi". LWT - Food Science and Technology. 56 (2): 406–413. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2013.11.001.

- ^ Gillman PK (2016). "Monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a review concerning dietary tyramine and drug interactions" (PDF). PsychoTropical Commentaries. 1: 1–90.

- ^ van Haelst IM, van Klei WA, Doodeman HJ, Kalkman CJ, Egberts TC (August 2012). "Antidepressive treatment with monoamine oxidase inhibitors and the occurrence of intraoperative hemodynamic events: a retrospective observational cohort study". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 73 (8): 1103–9. doi:10.4088/JCP.11m07607. PMID 22938842.

- ^ Smith MS, Muir H, Hall R (February 1996). "Perioperative management of drug therapy, clinical considerations". Drugs. 51 (2): 238–59. doi:10.2165/00003495-199651020-00005. PMID 8808166. S2CID 46972638.

- ^ Blom-Peters L, Lamy M (1993). "Monoamine oxidase inhibitors and anesthesia: an updated literature review". Acta Anaesthesiologica Belgica. 44 (2): 57–60. PMID 8237297.

- ^ Le Gassicke J, Ashcroft GW, Eccleston D, Evans JI, Oswald I, Ritson EB (1 April 1965). "The Clinical State, Sleep and Amine Metabolism of a Tranylcypromine ('Parnate') Addict". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 111 (473): 357–364. doi:10.1192/bjp.111.473.357. S2CID 145562899.

- ^ a b Lee MG, Wynder C, Schmidt DM, McCafferty DG, Shiekhattar R (June 2006). "Histone H3 lysine 4 demethylation is a target of nonselective antidepressive medications". Chemistry & Biology. 13 (6): 563–7. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.05.004. PMID 16793513.

- ^ Mast N, Charvet C, Pikuleva IA, Stout CD (October 2010). "Structural basis of drug binding to CYP46A1, an enzyme that controls cholesterol turnover in the brain". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 285 (41): 31783–95. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.143313. PMC 2951250. PMID 20667828.

- ^ Gaweska H, Fitzpatrick PF (October 2011). "Structures and Mechanism of the Monoamine Oxidase Family". Biomolecular Concepts. 2 (5): 365–377. doi:10.1515/BMC.2011.030. PMC 3197729. PMID 22022344.

- ^ Sherry RL, Rauw G, McKenna KF, Paetsch PR, Coutts RT, Baker GB (December 2000). "Failure to detect amphetamine or 1-amino-3-phenylpropane in humans or rats receiving the MAO inhibitor tranylcypromine". Journal of Affective Disorders. 61 (1–2): 23–9. doi:10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00188-3. PMID 11099737.

- ^ A US patent 4016204 A, Rajadhyaksha VJ, "Method of synthesis of trans-2-phenylcyclopropylamine", published 1977-04-05, assigned to Nelson Research & Development Company

- ^ Burger A, Yost WL (1948). "Arylcycloalkylamines. I. 2-Phenylcyclopropylamine". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 70 (6): 2198–2201. doi:10.1021/ja01186a062.

- ^ López-Muñoz F, Alamo C (2009). "Monoaminergic neurotransmission: the history of the discovery of antidepressants from 1950s until today". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 15 (14): 1563–86. doi:10.2174/138161209788168001. PMID 19442174.

- ^ Shorter E (2009). Before Prozac: the troubled history of mood disorders in psychiatry. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-536874-1.

- ^ Atchley DW (September 1964). "Reevaluation of Tranylcypromine Sulfate(Parnate Sulfate)". JAMA. 189 (10): 763–4. doi:10.1001/jama.1964.03070100057011. PMID 14174054.

- ^ a b c Zheng YC, Yu B, Jiang GZ, Feng XJ, He PX, Chu XY, et al. (2016). "Irreversible LSD1 Inhibitors: Application of Tranylcypromine and Its Derivatives in Cancer Treatment". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 16 (19): 2179–88. doi:10.2174/1568026616666160216154042. PMID 26881714.

- ^ Przespolewski A, Wang ES (July 2016). "Inhibitors of LSD1 as a potential therapy for acute myeloid leukemia". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 25 (7): 771–80. doi:10.1080/13543784.2016.1175432. PMID 27077938. S2CID 20858344.

- ^ Al-Nuaimi SK, Mackenzie EM, Baker GB (November 2012). "Monoamine oxidase inhibitors and neuroprotection: a review". American Journal of Therapeutics. 19 (6): 436–48. doi:10.1097/MJT.0b013e31825b9eb5. PMID 22960850.

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Non-specific |

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenethylamines (dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine) |

| ||||||||||

| Tryptamines (serotonin, melatonin) |

| ||||||||||

| Histamine |

| ||||||||||

| Receptor (ligands) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme (inhibitors) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Others | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phenethylamines |

|

|---|---|

| Amphetamines |

|

| Phentermines |

|

| Cathinones |

|

| Phenylisobutylamines | |

| Phenylalkylpyrrolidines | |

| Catecholamines (and close relatives) |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

| Subsidiaries |

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predecessors, acquisitions | |||||||||

| Products |

| ||||||||

| People |

| ||||||||

| Litigation | |||||||||

| Other | |||||||||

| |||||||||