| Dardic | |

|---|---|

| Hindu-Kush Indo-Aryan | |

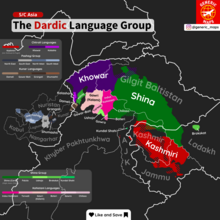

| Geographic distribution | Northern Pakistan (Gilgit-Baltistan, northern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Azad Kashmir) Northwestern India (Jammu and Kashmir, Ladakh) Northeastern Afghanistan (Kapisa, Kunar, Laghman, Nangarhar, Nuristan) |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | None dard1244 (Eastern Dardic) |

Dardic languages by Georg Morgenstierne (Note: Nuristani languages such as Kamkata-vari (Kati), Kalasha-ala (Waigali), etc. are now separated) | |

The Dardic languages (also Dardu or Pisaca),[1] or Hindu-Kush Indo-Aryan languages,[2][3][4][5] are a group of several Indo-Aryan languages spoken in northern Pakistan, northwestern India and parts of northeastern Afghanistan.[6] This region has sometimes been referred to as Dardistan.[7]

Rather than close linguistic or ethnic relationships, the original term Dardic was a geographical concept, denoting the northwesternmost group of Indo-Aryan languages,[8][9] There is no ethnic unity among the speakers of these languages nor can the languages be traced to a single ancestor.[10][11][12][6] After further research, the term "Eastern Dardic" is now a legitimate grouping of languages that excludes some languages in the Dardistan region that are now considered to be part of different language families.[13]

The extinct Gandhari language, used by the Gandhara civilization, from circa 1500 BCE, was Dardic in nature.[14] Linguistic evidence has linked Gandhari with some living Dardic languages, particularly Torwali and other Kohistani languages.[15][16][17] There is limited evidence that the Kohistani languages are descended from Gandhari.

History

[edit]Leitner's Dardistan, in its broadest sense, became the basis for the classification of the languages in the north-west of the Indo-Aryan linguistic area (which includes present-day eastern Afghanistan, northern Pakistan, and Kashmir).[18] George Abraham Grierson, with scant data, borrowed the term and proposed an independent Dardic family within the Indo-Iranian languages.[19] However, Grierson's formulation of Dardic is now considered to be incorrect in its details, and has therefore been rendered obsolete by modern scholarship.[20]

Georg Morgenstierne, who conducted an extensive fieldwork in the region during the early 20th century, revised Grierson's classification and came to the view that only the "Kafiri" (Nuristani) languages formed an independent branch of the Indo-Iranian languages separate from Indo-Aryan and Iranian families, and determined that the Dardic languages were unmistakably Indo-Aryan in character.[8]

Dardic languages contain absolutely no features which cannot be derived from old [Indo-Aryan language]. They have simply retained a number of striking archasisms, which had already disappeared in most Prakrit dialects... There is not a single common feature distinguishing Dardic, as a whole, from the rest of the [Indo-Aryan] languages... Dardic is simply a convenient term to denote a bundle of aberrant [Indo-Aryan] hill-languages which, in their relative isolation, accented in many cases by the invasion of Pathan tribes, have been in varying degrees sheltered against the expand influence of [Indo-Aryan] Midland (Madhyadesha) innovations, being left free to develop on their own.[21]

Due to their geographic isolation, many Dardic languages have preserved archaisms and other features of Old Indo-Aryan. These features include three sibilants, several types of clusters of consonants, and archaic or antiquated vocabulary lost in other modern Indo-Aryan languages.[22]

Kalasha and Khowar are the most archaic of all modern Indo-Aryan languages, retaining a great part of Sanskrit case inflexion, and retaining many words in a nearly Sanskritic form.[23][24] For example driga "long" in Kalasha is nearly identical to dīrghá in Sanskrit[25] and ašrú "tear" in Khowar is identical to the Sanskrit word.[26]

French Indologist Gérard Fussman points out that the term Dardic is geographic, not a linguistic expression.[27] Taken literally, it allows one to believe that all the languages spoken in Dardistan are Dardic.[27] It also allows one to believe that all the people speaking Dardic languages are Dards and the area they live in is Dardistan.[27] A term used by classical geographers to identify the area inhabited by an indefinite people, and used in Rajatarangini in reference to people outside Kashmir, has come to have ethnographic, geographic, and even political significance today.[12]

Classification

[edit]George Morgenstierne's scheme corresponds to recent scholarly consensus.[28] As such, the historic Dardic's position as a legitimate genetic subfamily has been repeatedly called into question; it is widely acknowledged that the grouping is more geographical in nature, as opposed to linguistic.[29] Indeed, Buddruss rejected the Dardic grouping entirely, and placed the languages within Central Indo-Aryan.[30] Other scholars, such as Strand[31] and Mock,[32] have similarly voiced doubts in this regard.

However, Kachru contrasts "Midland languages" spoken in the plains, such as Punjabi and Urdu, with "Mountain languages", such as Dardic.[33] Kogan has also suggested an 'East-Dardic' sub-family; comprising the 'Kashmiri', 'Kohistani' and 'Shina' groups.[34][35]

The case of Kashmiri is peculiar. Its Dardic features are close to Shina, often said to belong to an eastern Dardic language subfamily. Kachru notes that "the Kashmiri language used by Kashmiri Hindu Pandits has been powerfully influenced by Indian culture and literature, and the greater part of its vocabulary is now of Indian origin, and is allied to that of Sanskritic Indo-Aryan languages of northern India".[33]

While it is true that many Dardic languages have been influenced by non-Dardic languages, Dardic may have also influenced neighbouring Indo-Aryan lects in turn, such as Punjabi,[36] the Pahari languages, including the Central Pahari languages of Uttarakhand,[36][37] and purportedly even further afield.[38][39] Some linguists have posited that Dardic lects may have originally been spoken throughout a much larger region, stretching from the mouth of the Indus (in Sindh) northwards in an arc, and then eastwards through modern day Himachal Pradesh to Kumaon. However, this has not been conclusively established.[40][41][42]

Subdivisions

[edit]

Dardic languages have been organized into the following subfamilies:[43][34]

- Eastern Dardic languages:

- Chitrali languages: Kalasha (Urtsuniwar), Khowar

- Pashai languages: Pashai

- Kunar languages: Dameli, Gawar-Bati, Nangalami (Grangali), Shumashti

- Other Afghanistan languages: Wotapuri-Katarqalai, Tirahi

Characteristics

[edit]Loss of voiced aspiration

[edit]Virtually all Dardic languages have experienced a partial or complete loss of voiced aspirated consonants.[43][45] Khowar uses the word buum for 'earth' (Sanskrit: bhumi),1 Pashai uses the word duum for 'smoke' (Urdu: dhuān, Sanskrit: dhūma) and Kashmiri uses the word dọd for 'milk' (Sanskrit: dugdha, Urdu: dūdh).[43][45] Tonality has developed in most (but not all) Dardic languages, such as Khowar and Pashai, as a compensation.[45] Punjabi and Western Pahari languages similarly lost aspiration but have virtually all developed tonality to partially compensate (e.g. Punjabi kár for 'house', compare with Urdu ghar).[43]

Dardic metathesis and other changes

[edit]Both ancient and modern Dardic languages demonstrate a marked tendency towards metathesis where a "pre- or postconsonantal 'r' is shifted forward to a preceding syllable".[36][46] This was seen in Ashokan rock edicts (erected 269 BCE to 231 BCE) in the Gandhara region, where Dardic dialects were and still are widespread. Examples include a tendency to spell the Classical Sanskrit words priyadarshi (one of the titles of Emperor Ashoka) as instead priyadrashi and dharma as dhrama.[46] Modern-day Kalasha uses the word driga 'long' (Sanskrit: dirgha).[46] Palula uses drubalu 'weak' (Sanskrit: durbala) and brhuj 'birch tree' (Sanskrit: bhurja).[46] Kashmiri uses drạ̄lid2 'impoverished' (Sanskrit: daridra) and krama 'work' or 'action' (Sanskrit: karma).[46] Western Pahari languages (such as Dogri), Sindhi and Lahnda (Western Punjabi) also share this Dardic tendency to metathesis, though they are considered non-Dardic, for example cf. the Punjabi word drakhat 'tree' (from Persian darakht).[clarification needed][28][47]

Dardic languages also show other consonantal changes. Kashmiri, for instance, has a marked tendency to shift k to ch and j to z (e.g. zon 'person' is cognate to Sanskrit jan 'person or living being' and Persian jān 'life').[28]

Verb position in Dardic

[edit]Unique among the Dardic languages, Kashmiri presents "verb second" as the normal grammatical form. This is similar to many Germanic languages, such as German and Dutch, as well as Uto-Aztecan O'odham and Northeast Caucasian Ingush. All other Dardic languages, and more generally within Indo-Iranian, follow the subject-object-verb (SOV) pattern.[48]

| Language | First example sentence | Second example sentence |

|---|---|---|

| English (Germanic) | This is a horse. | We will go to Tokyo. |

| Kashmiri (Dardic) | Yi chu akh gur. | Ạs' gatshav Tokiyo. |

| Japanese (Japonic) | Kore wa uma de aru. | Watashitachi wa Tōkyō ni ikimasu. |

| Kamkata-vari (Nuristani) | Ina ušpa âsa. | Imo Tokyo âćamo. |

| Dari Persian (Iranian) | In yak asb ast. | Mâ ba Tokyo xâhem raft. |

| Shina (Dardic) | Anu ek aspo han. | Be Tokyo et bujun. |

| Pashto (Iranian) | Masculine: Dā yaw as day. / Feminine: Dā yawa aspa da. | Mūng/Mūẓ̌ ba Ṭokyo ta/tar lāṛšū. |

| Indus Kohistani (Dardic) | Sho akh gho thu. | Ma Tokyo ye bum-thu. |

| Sindhi (Indo-Aryan) | Heeu hiku ghoro aahe. | Asaan Tokyo veendaaseen. |

| Hindi-Urdu (Indo-Aryan) | Ye ek ghoṛa hain.4 | Ham Tokyo jāenge. |

| Punjabi (Indo-Aryan) | Iha ikk kòṛa ai. | Asin Tokyo jāvange. |

| Mandeali (Indo-Aryan) | Ye ek ghōṛā hā. | Āsā Tokyo jāṇā. |

| Nepali (Indo-Aryan) | Yo euta ghoda ho. | Hami Tokyo jānechhaũ. |

| Garhwali (Indo-Aryan) | Yuu ek ghoda cha. | Ham Tokyo Jaula. |

| Kumaoni (Indo-Aryan) | Yo ek ghwad chhu. | Ham Tokyo jaunl. |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- 1.^ The Khowar word for 'earth' is more accurately represented, with tonality, as buúm rather than buum, where ú indicates a rising tone.

- 2.^ The word drolid actually includes a Kashmiri half-vowel, which is difficult to render in the Urdu, Devnagri and Roman scripts alike. Sometimes, an umlaut is used when it occurs in conjunction with a vowel, so the word might be more accurately rendered as drölid.

- 3.^ Sandhi rules in Sanskrit allow the combination of multiple neighboring words together into a single word: for instance, word-final 'ah' plus word-initial 'a' merge into 'o'. In actual Sanskrit literature, with the effects of sandhi, this sentence would be expected to appear as Eṣá ékóśvósti. Also, word-final 'a' is Sanskrit is a schwa, [ə] (similar to the ending 'e' in the German name, Nietzsche), so e.g. the second word is pronounced [éːkə]. Pitch accent is indicated with an acute accent in the case of the older Vedic language, which was inherited from Proto-Indo-European.

- 4.^ Hindi-Urdu, and other non-Dardic Indo-Aryan languages, also sometimes utilize a "verb second" order (similar to Kashmiri and English) for dramatic effect.[49] Yeh ek ghoṛā hain is the normal conversational form in Hindi-Urdu. Yeh hain ek ghoṛā is also grammatically correct but indicates a dramatic revelation or other surprise. This dramatic form is often used in news headlines in Hindi-Urdu, Punjabi and other Indo-Aryan languages.

Sources

[edit]Academic literature from outside South Asia

- Morgenstierne, G. Irano-Dardica. Wiesbaden 1973;

- Morgenstierne, G. Die Stellung der Kafirsprachen. In Irano-Dardica, 327-343. Wiesbaden, Reichert 1975

- Decker, Kendall D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan, Volume 5. Languages of Chitral.

Academic literature from South Asia

- The Comparative study of Urdu and Khowar. Badshah Munir Bukhari National Language Authority Pakistan 2003. [No Reference]

- National Institute of Pakistani Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University & Summer Institute of Linguistics

Further reading

[edit]- Khan, Sawar, et al. "Ethnogenetic analysis reveals that Kohistanis of Pakistan were genetically linked to west Eurasians by a probable ancestral genepool from Eurasian steppe in the bronze age." Mitochondrion 47 (2019): 82-93.

References

[edit]- ^ "Dardic languages".

- ^ Liljegren, Henrik (1 March 2017). "Profiling Indo-Aryan in the Hindukush-Karakoram: A preliminary study of micro-typological patterns". Journal of South Asian Languages and Linguistics. 4 (1): 107–156. doi:10.1515/jsall-2017-0004. ISSN 2196-078X. S2CID 132833118.

On the one hand, it is obvious that these languages form a continuum together with the main Indo-Aryan languages of the northwestern Subcontinent, with a gradually increased clustering of more prototypical Hindukush-Karakoram features toward the central – but in relation to the rest of Indo-Aryan more peripheral – parts of this region. On the other hand, these languages also show a high degree of diversity, with individual languages taking part in various subareal configurations or transit zones that are represented in the region, further complicating any attempts at defining them collectively in more exact, or exclusive, areal terms. We must therefore bear in mind that any collective reference to these languages, be it Hindukush Indo-Aryan or any other term, will have to be interpreted as a highly gradient notion, acknowledging the apparent lack of any complete list of innovations, let alone retentions, that would cover more than a subset of them.

- ^ Garbo, Francesca Di; Olsson, Bruno; Wälchli, Bernhard (2019). Grammatical gender and linguistic complexity II: World-wide comparative studies. Language Science Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-3-96110-180-1.

- ^ Saxena, Anju (12 May 2011). Himalayan Languages: Past and Present. Walter de Gruyter. p. 35. ISBN 978-3-11-089887-3.

- ^ Liljegren, Henrik (26 February 2016). A grammar of Palula. Language Science Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-3-946234-31-9.

- ^ a b Strand, Richard F. (13 December 2013). "Dardic and Nūristānī languages". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John Abdallah; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam - Three 2013-4. Brill. pp. 101–103. ISBN 978-90-04-25269-1.

The seventeen Dardic languages constitute a geographic group of the northwestern-most Indo-Aryan languages. They fall into several small phylogenetic groups of Indo-Aryan, but together they show no common phonological innovations that demonstrate that they share any phylogenetic unity as a "Dardic branch" of the Indo-Aryan languages.

- ^ Kellens, Jean. "DARDESTĀN". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ a b Prakāśaṃ, Vennelakaṇṭi (2008). Encyclopaedia of the Linguistic Sciences: Issues and Theories. Allied Publishers. pp. 142–147. ISBN 978-81-8424-279-9.

Dardic languages contain absolutely no features which cannot be derived from old [Indo-Aryan language]. They have simply retained a number of striking archasisms, which had already disappeared in most Prakrit dialects... There is not a single common feature distinguishing Dardic, as a whole, from the rest of the [Indo-Aryan] languages... Dardic is simply a convenient term to denote a bundle of aberrant [Indo-Aryan] hill-languages which, in their relative isolation, accented in many cases by the invasion of Pathan tribes, have been in varying degrees sheltered against the expand influence of [Indo-Aryan] Midland (Madhyadesha) innovations, being left free to develop on their own.

- ^ Kaw, M. K. (2004). Kashmir and It's People: Studies in the Evolution of Kashmiri Society. APH Publishing. p. 295. ISBN 978-81-7648-537-1.

The term Dardic is stated to be only a geographical convention and not a linguistic expression.

- ^ Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (26 July 2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. p. 822. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

The designation "Dardic" implies neither ethnic unity among the speakers of these languages nor that they can all be traced to a single stammbaum-model node.

- ^ Verbeke, Saartje (20 November 2017). Argument structure in Kashmiri: Form and function of pronominal suffixation. BRILL. p. 2. ISBN 978-90-04-34678-9.

Nowadays, the term "Dardic" is used as an areal term that refers to a number of Indo-Aryan languages, without claiming anything specific about their mutual relatedness.

- ^ a b "Dards, Dardistan, and Dardic: an Ethnographic, Geographic, and Linguistic Conundrum". www.mockandoneil.com. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Glottolog 4.8 - Eastern Dardic".

- ^ Kuzʹmina, Elena Efimovna (2007). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. BRILL. p. 318. ISBN 978-90-04-16054-5.

- ^ Dani, Ahmad Hasan (2001). History of Northern Areas of Pakistan: Upto 2000 A.D. Sang-e-Meel Publications. pp. 64–67. ISBN 978-969-35-1231-1.

- ^ Saxena, Anju (12 May 2011). Himalayan Languages: Past and Present. Walter de Gruyter. p. 35. ISBN 978-3-11-089887-3.

- ^ Liljegren, Henrik (26 February 2016). A grammar of Palula. Language Science Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-3-946234-31-9.

Palula belongs to a group of Indo-Aryan (IA) languages spoken in the Hindukush region that are often referred to as "Dardic" languages... It has been and is still disputed to what extent this primarily geographically defined grouping has any real classificatory validity... On the one hand, Strand suggests that the term should be discarded altogether, holding that there is no justification whatsoever for any such grouping (in addition to the term itself having a problematic history of use), and prefers to make a finer classification of these languages into smaller genealogical groups directly under the IA heading, a classification we shall return to shortly... Zoller identifies the Dardic languages as the modern successors of the Middle Indo-Aryan (MIA) language Gandhari (also Gandhari Prakrit), but along with Bashir, Zoller concludes that the family tree model alone will not explain all the historical developments.

- ^ Bhan, Mona (11 September 2013). Counterinsurgency, Democracy, and the Politics of Identity in India: From Warfare to Welfare?. Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-134-50983-6.

- ^ Masica 1993, p. 461.

- ^ Emeneau, Murray B.; Fergusson, Charles A. (21 November 2016). Linguistics in South Asia. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 285. ISBN 978-3-11-081950-2.

- ^ Koul 2008, p. 142.

- ^ Kaw, M. K. (2004). Kashmir and It's People: Studies in the Evolution of Kashmiri Society. APH Publishing. p. 341. ISBN 978-81-7648-537-1.

- ^ Dani, Ahmad Hasan (2001). History of Northern Areas of Pakistan: Upto 2000 A.D. Sang-e-Meel Publications. p. 66. ISBN 978-969-35-1231-1.

Khowar and Kalasha are among the most archaic Indo-Aryan languages. Both are related to Gandhari and share some very characteristic archaisms (for instance old Indo-Aryan -t-, disappeared from other Indo-Ayran languages, -l/r- in Kalasha and Khowar).

- ^ Morgenstierne, Georg (1974). "Languages of Nuristan and surrounding regions". In Jettmar, Karl; Edelberg, Lennart (eds.). Cultures of the Hindukush: selected papers from the Hindu-Kush Cultural Conference held at Moesgård 1970. Beiträge zur Südasienforschung, Südasien-Institut Universität Heidelberg. Vol. Bd. 1. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner. pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-3-515-01217-1.

- ^ Baldi, Sergio (28 November 2016). "Kalasha Grammar Based on Fieldwork Research, written by Elizabeth Mela-Athanasopoulou". Annali Sezione Orientale. 76 (1–2): 265–266. doi:10.1163/24685631-12340012.

- ^ Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (26 July 2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. p. 973. ISBN 978-1-135-79710-2.

- ^ a b c Prakāśaṃ, Vennelakaṇṭi (2008). Encyclopaedia of the Linguistic Sciences: Issues and Theories. Allied Publishers. p. 143. ISBN 978-81-8424-279-9.

- ^ a b c Masica 1993.

- ^ Bashir, Elena (2007). Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (eds.). The Indo-Aryan languages. Routledge. p. 905. ISBN 978-0415772945.

'Dardic' is a geographic cover term for those Northwest Indo-Aryan languages which [..] developed new characteristics different from the IA languages of the Indo-Gangetic plain. Although the Dardic and Nuristani (previously 'Kafiri') languages were formerly grouped together, Morgenstierne (1965) has established that the Dardic languages are Indo-Aryan, and that the Nuristani languages constitute a separate subgroup of Indo-Iranian.

- ^ Buddruss, Georg (1985). "Linguistic Research in Gilgit and Hunza". Journal of Central Asia. 8 (1): 27–32.

- ^ Strand, Richard (2001), "The Tongues of Peristân"

- ^ Mock, John (2011), "http://www.mockandoneil.com/dard.htm"

- ^ a b Kachru, Braj B. (1981), Kashmiri Literature, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 4–5, ISBN 978-3-447-02129-6

- ^ a b Kogan, Anton (2013), "https://jolr.ru/index.php?article=130"

- ^ Kogan, Anton (2015), "https://jolr.ru/index.php?article=157"

- ^ a b c Masica 1993, p. 452: ... [Chaterji] agreed with Grierson in seeing Rajasthani influence on Pahari and 'Dardic' influence on (or under) the whole Northwestern group + Pahari. Masica 1993, p. 209: Throughout the northwest, beginning with Sindhi and including 'Lahnda', Dardic, Romany and West Pahari, there has been a tendency to [the] transfer of 'r' from medial clusters to a position after the initial consonant.

- ^ Arun Kumar Biswas (editor) (1985), Profiles in Indian languages and literatures, Indian Languages Society,

... greater Dardic influence in the western dialects of Garhwali ...

((citation)):|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Dayanand Narasinh Shanbhag; K. J. Mahale (1970), Essays on Konkani language and literature: Professor Armando Menezes felicitation volume, Konkani Sahitya Prakashan,

... Konkani is spoken. It shows a good deal of Dardic (Paisachi) influence ...

- ^ Gulam Allana (2002), The origin and growth of Sindhi language, Institute of Sindhology, ISBN 9789694050515,

... must have covered nearly the whole of the Punjabi ... still show traces of the earlier Dardic languages that they superseded. Still further south, we find traces of Dardic in Sindhi ...

- ^ Irach Jehangir Sorabji Taraporewala (1932), Elements of the science of language, University of Calcutta, retrieved 12 May 2010,

At one period, the Dardic languages spread over a very much wider extent, but before the oncoming 'outer Aryans' as well as owing to the subsequent expansion of the 'Inner Aryans', the Dards fell back to the inaccessible ...

- ^ Sharad Singh Negi (1993), Kumaun: the land and the people, Indus Publishing, ISBN 81-85182-89-2, retrieved 12 May 2010,

It may be possible that the Dardic speaking Aryans were still in the process of settling in other parts of the western Himalaya in the Mauryan times ...

- ^ Sudhakar Chattopadhyaya (1973), Racial affinities of early North Indian tribes, Munshiram Manoharlal, retrieved 12 May 2010,

... the Dradic branch remained in northwest India – the Daradas, Kasmiras, and some of the Khasas (some having been left behind in the Himalayas of Nepal and Kumaon) ...

- ^ a b c d S. Munshi, Keith Brown (editor), Sarah Ogilvie (editor) (2008), Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world, Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-08-087774-7, retrieved 11 May 2010,

Based on historical sub-grouping approximations and geographical distribution, Bashir (2003) provides six sub-groups of the Dardic languages ...

((citation)):|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nicolaus, Peter (2015). "Residues of Ancient Beliefs among the Shin in the Gilgit-Division and Western Ladakh". Iran & the Caucasus. 19 (3): 201–264. doi:10.1163/1573384X-20150302. ISSN 1609-8498. JSTOR 43899199.

- ^ a b c George Cardona; Dhanesh Jain (2007), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5, retrieved 11 May 2010,

In others, traces remain as tonal differences (Khowar buúm, 'earth', Pashai dum, 'smoke') ...

- ^ a b c d e Timothy Lenz; Andrew Glass; Dharmamitra Bhikshu (2003), A new version of the Gandhari Dharmapada and a collection of previous-birth stories, University of Washington Press, ISBN 0-295-98308-6, retrieved 11 May 2010,

... 'Dardic metathesis,' wherein pre- or postconsonantal 'r' is shifted forward to a preceding syllable ... earliest examples come from the Aśokan inscriptions ... priyadarśi ... as priyadraśi ... dharma as dhrama ... common in modern Dardic languages ...

- ^ Amar Nath Malik (1995), The phonology and morphology of Panjabi, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, ISBN 81-215-0644-1, retrieved 26 May 2010,

... drakhat 'tree' ...

- ^ Stephen R. Anderson (2005), Aspects of the theory of clitics: Volume 11 of Oxford studies in theoretical linguistics, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-927990-6,

The literature on the verb-second construction has concentrated largely on Germanic ... we can compare with the Germanic phenomena, however: Kashmiri ... in two 'Himachali' languages, Kotgarhi and Koci, he finds word-order patterns quite similar ... they are sometimes said to be part of a 'Dardic' subfamily ...

- ^ Hindi: language, discourse, and writing, Volume 2, Mahatma Gandhi International Hindi University, 2001, retrieved 28 May 2010,

... the verbs, positioned in the middle of the sentences (rather than at the end) intensify the dramatic quality ...

Bibliography

[edit]- Koul, Omkar N. (2008), "Dardic Languages", in Vennelakanti Prakāśam (ed.), Encyclopaedia of the Linguistic Sciences: Issues and Theories, Allied Publishers, pp. 142–147, ISBN 978-81-8424-279-9

- Masica, Colin P. (1993), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2

| Dardic |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Northwestern |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Western |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Central |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eastern |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Southern |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Middle |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proto- languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unclassified | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pidgins and creoles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||