Medication

Flibanserin, sold under the brand name Addyi, is a medication approved for the treatment of pre-menopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD).[4][5] The medication improves sexual desire, increases the number of satisfying sexual events, and decreases the distress associated with low sexual desire.[6] The most common side effects are dizziness, sleepiness, nausea, difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep and dry mouth.[6]

Development by Boehringer Ingelheim was halted in October 2010, following a negative evaluation by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[7] The rights to the drug were then transferred to Sprout Pharmaceuticals, which achieved approval of the drug by the US FDA in August 2015.[8]

Addyi is approved for medical use in the US for premenopausal women with HSDD and in Canada for premenopausal and postmenopausal women with HSDD.[6][9]

HSDD was recognized as a distinct sexual function disorder for more than 30 years, but was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 2013, and replaced with a new diagnosis called female sexual interest/arousal disorder (FSIAD).[10][11]

Medical uses

Flibanserin is used for hypoactive sexual desire disorder among women. The onset of the flibanserin effect was seen from the first timepoint measured after 4 weeks of treatment and maintained throughout the treatment period.[12][3]

The effectiveness of flibanserin was evaluated in three phase 3 clinical trials. Each of the three trials had two co-primary endpoints, one for satisfying sexual events (SSEs) and the other for sexual desire. Each of the 3 trials also had a secondary endpoint that measured distress related to sexual desire. All three trials showed that flibanserin produced an increase in the number of SSEs and reduced distress related to sexual desire. The first two trials used an electronic diary to measure sexual desire, and did not find an increase. These two trials also measured sexual desire using the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) as a secondary endpoint, and an increase was observed using this latter measure. The FSFI was used as the co-primary endpoint for sexual desire in the third trial, and again showed a statistically significant increase.[3]

Supportive analyses based on the patient's perspective of her symptoms at the end of the study showed that improvements in symptoms of HSDD were not only statistically significant but also clinically meaningful to women.[13]

Side effects

The majority of adverse events were mild to moderate in severity. The most commonly reported adverse events included dizziness, nausea, feeling tired, sleepiness, and trouble sleeping.[6]

Drinking alcohol while on flibanserin may increase the risk of severe low blood pressure. The Addyi Prescribing Information was updated in 2019 following the FDA's review of three postmarketing alcohol interaction studies which led to increased understanding of this drug interaction. This new data led to a removal of the contraindication with alcohol and new recommendations on how to safely consume alcohol while receiving Addyi therapy.

Current recommendations are to wait at least two hours after consuming one or two standard alcoholic drinks before taking ADDYI at bedtime or to skip their ADDYI dose if they have consumed three or more standard alcoholic drinks that evening.[6]

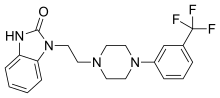

Mechanism of action

Activity profile

Flibanserin acts as a full agonist in the frontal cortex and the Dorsal Raphe Nucleus, but only as a partial agonist in the CA3 region of the hippocampus[14] of the 5-HT1A receptor (serotonin receptor) (Ki = 1 nM in CHO cells, but only 15–50 nM in cortex, hippocampus and dorsal raphe)[4] and, with lower affinity, as an antagonist of the 5-HT2A receptor (Ki = 49 nM) and antagonist or very weak partial agonist of the D4 receptor (Ki = 4–24 nM,[15] Ki = 8–650 nM [16]).[17][18][19] Despite the much greater affinity of flibanserin for the 5-HT1A receptor, and for reasons that are unknown (although it might be caused by the competition with endogenous serotonin), flibanserin occupies the 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors in vivo with similar percentages.[4][20] Flibanserin also has low affinity for the 5-HT2B receptor (Ki = 89.3 nM) and the 5-HT2C receptor (Ki = 88.3 nM), both of which it behaves as an antagonist of.[19] Flibanserin preferentially activates 5-HT1A receptors in the prefrontal cortex, demonstrating regional selectivity, and has been found to increase dopamine and norepinephrine levels and decrease serotonin levels in the rat prefrontal cortex, actions that were determined to be mediated by activation of the 5-HT1A receptor.[17] As such, flibanserin has been described as a norepinephrine–dopamine disinhibitor (NDDI).[19][21]

The proposed mechanism of action refers to the Kinsey dual control model of sexual response.[22] Various neurotransmitters, sex steroids, and other hormones have important excitatory or inhibitory effects on the sexual response. Among neurotransmitters, excitatory activity is driven by dopamine and norepinephrine, while inhibitory activity is driven by serotonin. The balance between these systems is of significance for a normal sexual response. By modulating serotonin and dopamine activity in certain parts of the brain, flibanserin may improve the balance between these neurotransmitter systems in the regulation of sexual response.[23][24]

Society and culture

Flibanserin was originally developed as an antidepressant,[25][17] but was found to have pro-sexual effects and was later repurposed for the treatment of HSDD.

Names

Former proposed but abandoned brand names of flibanserin include Ectris and Girosa, and its former developmental code name was BIMT-17.[citation needed] The brand name is Addyi.

Approval process and advocacy

On June 18, 2010, a federal advisory panel to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) unanimously voted against recommending approval of flibanserin, citing an inadequate risk-benefit ratio. The Committee acknowledged the validity of hypoactive sexual desire as a diagnosis, but expressed concern with the drug's side effects and insufficient evidence for efficacy, especially the drug's failure to show a statistically significant effect on the co-primary endpoint of sexual desire.[26] Earlier in the week, a FDA staff report also recommended non-approval of the drug. Ahead of the votes, Boehringer Ingelheim had mounted a publicity campaign to promote the controversial disorder of "hypoactive sexual desire".[27] In 2010 the FDA issued a Complete Response Letter, stating that the New Drug Application could not be approved in its current form. The letter cited several concerns, including the failure to demonstrate a statistical effect on the co-primary endpoint of sexual desire and overly restrictive entry criteria for the two Phase 3 trials. The Agency recommended performing a new Phase 3 trial with less restrictive entry criteria.[28] On October 8, 2010, Boehringer announced that it would discontinue its development of flibanserin in light of the FDA's decision.[29]

Sprout responded to the FDA's cited deficiencies and refiled the NDA in 2013. The submission included data from a new Phase 3 trial and several Phase 1 drug-drug interaction studies.[28][30] The FDA again refused the application, citing an uncertain risk/benefit ratio. In December 2013, a Formal Dispute Resolution was filed,[31] which contained the requirements of the FDA for further studies. These include two studies in healthy subjects to determine if flibanserin impairs their ability to drive, and to determine if it interferes with other biochemical pathways. The Agency agreed to call a new Advisory Committee meeting to consider whether the risk-benefit ratio of flibanserin was favorable after this additional data was obtained.[31][32][33] Sprout expected to resubmit the New Drug Application (NDA) in the 3rd quarter of 2014.[31][32]

On June 4, 2015, the US FDA Advisory Committee, which includes the Bone, Reproductive, and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee (BRUDAC) and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee (DSRM), recommended approval of the drug by 18–6, with the proviso that measures be taken to inform women of the drug's side effects.[34][35] On August 18, 2015, the FDA approved Addyi (Flibanserin) for the treatment of premenopausal women with low sexual desire that causes personal distress or relationship difficulties. The approval specified that flibanserin should not be used to treat low sexual desire caused by co-existing psychiatric or medical problems; low sexual desire caused by problems in the relationship; or low sexual desire due to medication side effects.[3]

As of 21 August 2015, The Pharmaceutical Journal reported that Sprout Pharmaceuticals had not yet made an application to the European Medicines Agency for a marketing authorisation.[36]

Advocacy groups

Even the Score, a coalition of women's groups brought together by a Sprout consultant, actively campaigned for the approval of flibanserin. The campaign emphasized that several approved treatments for male sexual dysfunction exist, while no such treatment for women was available.[37] The group successfully obtained letters of support from the President of the National Organization for Women, the editor of the Journal of Sexual Medicine, and several members of Congress.[38]

Other organizations supporting the approval of flibanserin included the National Council of Women's Organizations, the Black Women's Health Imperative, the Association of Reproductive Health Professionals, National Consumers League, and the American Sexual Health Association.[39][40][41][42]

The approval was opposed by the National Women's Health Network, the National Center for Health Research and Our Bodies Ourselves.[43] A representative of PharmedOut said "To approve this drug will set the worst kind of precedent — that companies that spend enough money can force the FDA to approve useless or dangerous drugs."[44] An editorial in JAMA noted that, "Although flibanserin is not the first product to be supported by a consumer advocacy group in turn supported by pharmaceutical manufacturers, claims of gender bias regarding the FDA's regulation have been particularly noteworthy, as have the extent of advocacy efforts ranging from social media campaigns to letters from members of Congress".[45]

The Even the Score campaign was managed by Blue Engine Message & Media, a public relations firm, and received funding from Sprout.[46]

Acquisition by Valeant Pharmaceuticals

On 20 August 2015 Valeant Pharmaceuticals and Sprout Pharmaceuticals announced that Valeant will acquire Sprout, on a debt-free basis, for approximately $1 billion in cash, plus a share of future profits based upon the achievement of certain milestones.[47]

Reception

The initial response since the 2015 introduction of flibanserin to the U.S. market was slow with 227 prescriptions written during the first three weeks.[48] The slow response may be related to a number of factors: physicians require about 10 minutes of online training to get certified; the medication has to be taken daily and costs about US$400 per month;[49] and questions about the drug's efficacy and need.[48] Prescriptions for the drug continue to be few with less than 4,000 being made as of February 2016.[50]